Why The Latest Moderate Criticisms of Free College Don’t Make Sense

Some presidential candidates' critiques promote unhelpful assumptions about who tuition-free and debt-free college would really serve. (Spoiler: it's not millionaires and billionaires.)

Wednesday night marked the fifth debate of the 2020 Democratic primary, and free college emerged as one policy area where candidates continued to draw contrasts both on and off the debate stage. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders touted their proposals for universal tuition-free college and student loan forgiveness. Senator Warren powerfully laid out the case for why tackling college costs and debt are issues of racial and economic justice, saying:

“Let me give a specific example, and that is student loan debt. Right now in America, African-Americans are more likely to borrow money to go to college, borrow more money while they're in college, and have a harder time paying that debt off after they get out.”

Others have sounded a more skeptical note. South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg released a plan this week to make public college tuition-free for everyone making under $100,000; he emphasized who it would not include, saying:

Senator Amy Klobuchar signaled her opposition to the policy by saying, “I'd love to do more. As I've said before, I'd love to staple free diplomas under people's chairs… I am not going to go for things just because they sound good on a bumper sticker and then throw in a free car.”

We can debate the exact adhesive we use when handing out college degrees, but both criticisms are pretty off the mark and betray some unhelpful assumptions about who tuition-free and debt-free college would serve. As Jordan Weissman at Slate and Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute both lay out, a microscopic percentage of funding for free public college would flow to the families of millionaires and billionaires. According to Konczal, about 1.4 percent of the new benefits of free college would go to the top 1 percent.

Among the small but extremely wealthy slice of families that earn over $1 million a year, only a third send their children to public college, compared to over three-quarters of non-millionaire students:

Percent of Dependent Children Attending Public and Private College, 2016

|

Public |

Private Non-Profit |

|

|

Parents Earning Under $1 million |

77.6% |

18.2% |

|

Parents Earning $1 million or more |

35.3% |

63.5% |

Demos Calculations from Department of Education, 2015-16 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:16).

Further, a full quarter of wealthy students who are going to public colleges attend a school out of state, meaning they would not be eligible for the free college benefit under either the Warren or Sanders plan; both propose universal free tuition for students attending public in-state schools.

These comments from Buttigieg and Klobuchar illustrate the power of path dependency in our politics.

Most importantly, though, these comments from Buttigieg and Klobuchar illustrate the power of path dependency in our politics. The fear from free-college skeptics seems to be that by lowering tuition to zero at public 4-year colleges, public resources will go to those who could afford to pay something for their education without going destitute. It’s a logical, if limited, argument. For Klobuchar, who supports free community college, the argument does not seem to apply at public 2-year schools.

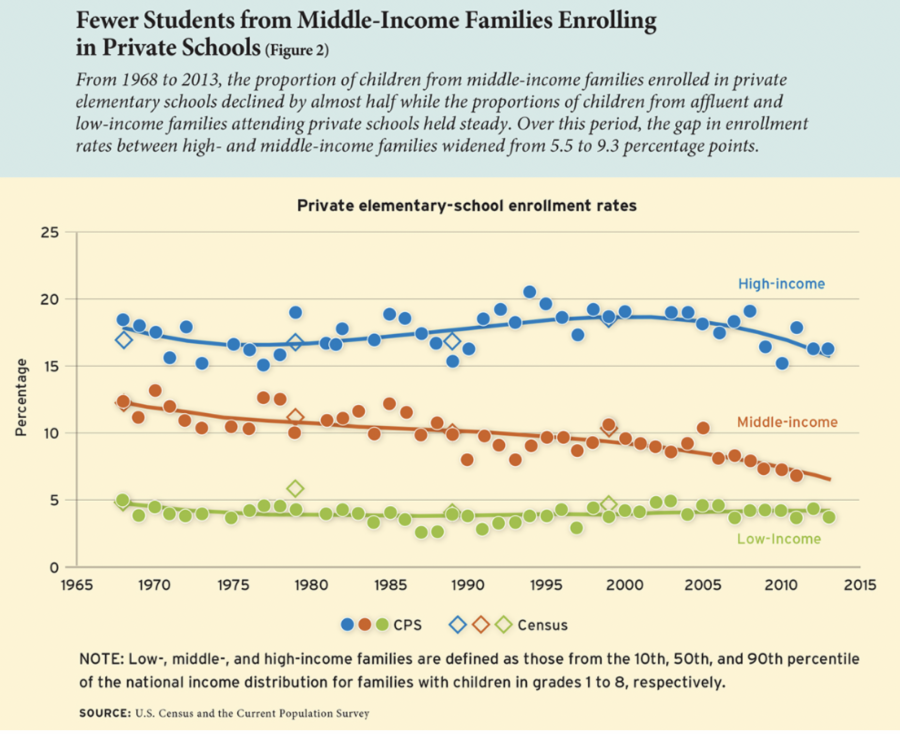

It’s also striking to note another area where people do not seem to have this fear: K-12 education. This is despite the fact that wealthy families send their children to public elementary schools at higher rates than they do public colleges. A 2018 study in Education Next found that only about 16 percent of wealthy families (those in the 90th income percentile earning a bit more than $180,000 a year) enroll their kids in private elementary schools, a figure that has remained steady over time.

Meanwhile, a quick look at U.S. Department of Education data shows that wealthy families are less likely than other families to send their children to public colleges. Only 67 percent of rich families send their kids to public colleges, compared to at least 78 percent of less-wealthy families. But upwards of 85 percent of rich families send their children to public elementary schools.1

Where Parents Send Dependent Children to College, by Sector and Income

|

Public |

Private nonprofit |

Private for-profit |

|

|

All students |

74.5% |

15.6% |

9.9% |

|

Parents' Income Percentile |

|||

|

Bottom Half |

79.5% |

14.2% |

6.3% |

|

50th to 90th |

78.0% |

19.6% |

2.4% |

|

90th and above |

67.5% |

31.4% |

1.1% |

Demos Calculations from Department of Education, 2015-16 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:16).

To be clear, this isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison—the Education Next study stops at 2013 and is derived from a statistical model examining families in the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile, while the Department of Education data is a survey of students in 2016.

If we value K-12 education as a universal public good, we should start doing so for higher education.

But it does indicate that if candidates are concerned about public schools being chock-full of wealthy students, higher education is probably the wrong target. Of course, no reasonable person would argue, based on this finding, that we should start charging tuition at public K-12 schools. That’s because tuition-free elementary, middle, and high school is the norm – in addition to being compulsory – and it would be very disruptive and counterproductive to the goal of an educated citizenry to change that norm. If we value K-12 education as a universal public good, we should start doing so for higher education.

None of this is to say that a system of free college should abandon America’s long history of private higher education, particularly the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) that have done the lion’s share of educating and supporting black college students for the better part of two centuries. In fact, Senators Warren, Sanders, and Mayor Buttigieg have all proposed more funding for private HBCUs and other Minority Serving Institutions. Any free college plan should include more funding and capacity-building for the institutions that enroll and graduate black and brown students.

It’s also worth examining the assumption that rich students attending public college is a bad thing on its face. There is a chance that a flood of rich students at public colleges would crowd out space for poor and working-class students. And of course, any free college plan should work to maintain and expand capacity and funding, and steer resources in ways that help students graduate. Luckily, every plan proposed thus far, including Senator Warren’s, nods to the need for more resources for all students, regardless of tuition levels, and a maintenance of effort across states that participate.

There’s also a high likelihood that a more socio-economically diverse public college system would have more defenses against state and federal lawmakers who have cut per-student funding over the past several decades. Evidence suggests that free-tuition schemes are more robust and less likely to be eliminated when the budget-cutters come. In either event, it does not seem likely that wealthy parents are price-sensitive enough that free public college will cause them to enroll their students en masse, when the current system of cheaper public college has not.

There are some defensible tradeoffs—more defensible in states with real budget constraints—in limiting free college to a specific sector such as community colleges, or by socio-economic status if it means that the non-tuition burdens for low- and middle-income students can be covered. But the idea that making public colleges free will provide a giant benefit to the ultra-wealthy is both off the mark and applied unevenly.

- 1In fact, this gap is likely even wider. It’s also important to note that K-12 education is compulsory in every state, while higher education is not. Since the National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey only includes those enrolled in college, it does not include children of rich families who do not enroll in college at all. Data show that about 78% of 9th graders in 2009 from families from the top income quintile were enrolled in college in 2016. So there is a small percentage of wealthy students who not only aren’t enrolled in public colleges, they’re not attending college at all.