These are the Questions We Should Be Asking in the Student Debt Cancellation Debate

In the past week, the idea of canceling student debt has been a topic of considerable debate on social media, in our nation’s op-ed pages and news outlets, and even during the first presidential primary debates of the 2020 cycle. Sparked by dueling proposals from Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, and by years of tireless work by student and borrower advocates, the idea of simply writing off some, or all, of the $1.5 trillion student debt in the economy is now a serious public policy discussion and should be celebrated accordingly. This is especially exciting given the role that student debt cancellation could play in ensuring generational and racial economic justice.

Distinguishing Between Warren and Sanders Debt Cancellation Plans

There has been considerable confusion or conflation between the plans proposed by Sens. Warren and Sanders, so it’s worth stepping back to acknowledge what each plan would do. Senator Warren proposes eliminating up to $50,000 in student loans for everyone with household income of $100,000 or less per year. People in households earning above $100,000 per year would receive roughly one-third less in debt cancellation for every dollar of household income above $100,000. Anyone with household income above $250,000 per year would not be eligible to have their loans forgiven.

Senator Sanders has proposed wiping away all student loan debt for borrowers who currently have it. His plan can be reasonably described as a $1.5 trillion economic stimulus for those with student loans. Both senators have proposed similar versions of tuition-free college going forward, while Senator Warren has also called for a large increase in Pell Grants to cover the non-tuition expenses that students take on debt to afford.

It is vital to remember that for about 75% of those with student loans, the plans’ impact would be exactly the same.

Despite the slight differences in design, it is vital to remember that for about 75 percent of those with student loans, the plans’ impact would be exactly the same. This is because three-quarters of student loan borrowers have less than $50,000 of student loan debt and have household incomes well below $250,000 a year. Warren’s campaign estimates that her plan would offer some forgiveness for around 95% of all student loan borrowers, meaning both plans are functionally the same for an overwhelming majority of borrowers.

To the extent that there are policy disagreements and distinctions between the Warren and Sanders student debt plans, they stem from the group of borrowers who receive total cancellation under the Sanders plan but only partial, or no, relief from the Warren plan. This makes up about 25 percent of all people with student debt. Given the design of the Warren plan, this consists of two categories of borrowers:

- Those whose household income is more than $250,000 per year, who would receive nothing.

- Those with more than $50,000 in debt, who would see some, but not all, of their debt wiped away.

The $250,000 group is, by definition, high-income. Analyzing the second group requires a few assumptions. First, there are limits on the total amount of federal student loans that students can borrow for undergraduate education. Dependent students can borrow up to $31,000, while independent students can borrow up to $57,500. The second thing to note is that the average student debt for a bachelor’s degree recipient is currently around $30,000. Those with greater than $50,000 in debt are largely made up of borrowers who have attended graduate school.

Senator Warren’s plan would provide broad relief while narrowing the black-white wealth gap.

It is for this reason that Senator Warren’s plan limits relief by the amount of debt and household income. As a result, her plan would provide broad relief while narrowing the black-white wealth gap. Previous research from Demos and the Institute on Assets and Social Policy has shown that canceling all debt would widen the racial wealth gap, since high-debt, high-income borrowers are disproportionately white. Targeted relief can narrow the wealth gap.

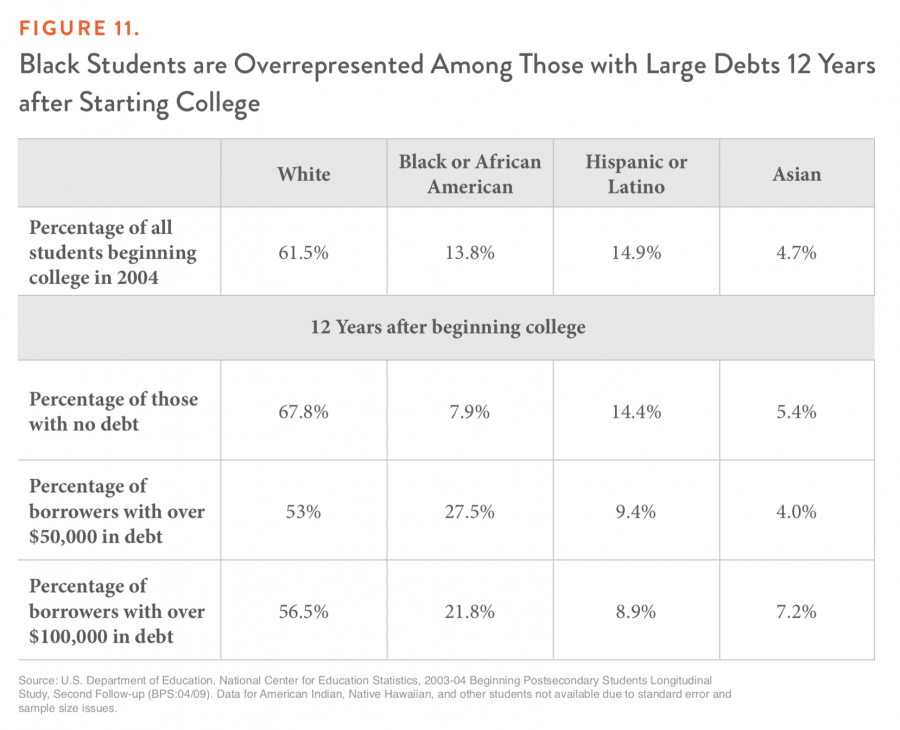

Of course, household income is only one way to measure financial well-being, and many borrowers with high graduate school debts are struggling to offload that debt in some way. They may be able to meet monthly payments but may be putting off all manner of activities that would benefit themselves and the economy. In addition, among those who make it to college and beyond, African-American borrowers are overrepresented among those with more than $50,000 of debt.

It is also potentially simpler to communicate a policy of total cancellation rather than one that works on a (relatively simple, but still) sliding scale. That simplicity comes at the cost of offloading the debt of a group of high-income, disproportionately white households.

Going Forward: Questions for Critics and Supporters

Both the Sanders and Warren plans have been met with considerable enthusiasm since their respective announcements. And given their similarities, both plans have come under similar pushback from a few distinct camps who might otherwise be amenable to spending more resources on borrowers (and higher education more broadly). For simplicity’s sake I have labeled these camps progressive and technocratic. The general contours of these arguments are as follows:

- Progressive critics might say that we should provide cash, or cash-like, assistance for poor and middle-class families, rather than limiting such a windfall to only those with student loans. In addition, massive student debt cancellation without further making graduate school free, or debt-free, means that future generations with graduate degrees, while just as deserving of relief, may never receive it.

- Technocratic critics often say that equitable policy results can be better achieved mostly through existing programs, including tools like income-driven loan repayment. Student debt is primarily good, payable debt, and calling it a problem may prevent people from borrowing and going to college. Giving resources to middle- and high-income households is “regressive.” And in any event, the resources required to undertake student loan forgiveness on a large scale are not worth fighting for at this time.

This debate is sure to rematerialize over the next few years and beyond. In the spirit, I have outlined several questions that I think would be worthwhile for technocratic critics of debt cancellation to answer. These include:

- Some criticisms that student debt cancellation is “regressive” could apply to much of higher education spending as it currently exists—particularly at the state level, but at the federal level as well—since higher education spending (by definition) goes toward those who go to college, and those who go to college tend to be wealthier. Should there be more pushback for overall spending on higher education, less pushback on debt relief, or neither?

- Debt cancellation currently exists for those whose schools have either engaged in fraud or malfeasance or otherwise shut down. It also exists for those who work in public service for 10 years. But the implementation of these loan forgiveness plans has been mixed at best, and in many cases stymied by Betsy DeVos and the current Department of Education. Do the implementation hurdles or outright sabotage of targeted, narrow, loan forgiveness plans make you more or less likely to believe broad relief might make more sense?

- Do the proposed financing mechanisms of student debt cancellation—a tax on financial transactions, or a tax on extremely wealthy households—change your view of either plan? Why or why not?

- Should any student debt be canceled? If so, who is “deserving” of cancellation, and on what timeline?

- Is it concerning that for the bottom 50 percent of all U.S. households, student debt grew from about a quarter of average yearly income to nearly three-fifths between the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s? Is this a better or worse metric of defining whether student debt is a burden?

- If the current tools at our disposal are mostly sufficient, why have student loan delinquencies risen and defaults remained persistently high?

- If all future students were provided with a pathway to a debt-free public college going forward, as proposed by members of Congress and candidates for higher office, does that make student debt cancellation more or less reasonable?

While I remain broadly supportive of student debt cancellation, there are some very reasonable questions that we should answer if we’re going to maximize the impact of such a policy. They include:

- Even if all $1.5 trillion of student debt were canceled tomorrow, students would continue to borrow in the future, including those going on to graduate and professional programs, those attending expensive private institutions, and some other groups. What are the best ways to build a safety net for those borrowers?

- Even if students could get a quality, debt-free undergraduate education, what are the best ways to keep institutions at the graduate level, or private schools, from loading up students with unmanageable debt?

- In a policy of targeted debt relief, students who receive partial forgiveness may have loans of varying interest rates and terms. Should the government decide which types of loans are canceled first, or should borrowers themselves dictate which are forgiven?

- Are there ways to compensate those who struggled but ultimately paid off their student loans and would not see any relief from this new policy? Should that be a priority?

Undoubtedly, many more questions will surface as this idea continues to weave its way through the 2020 discussion and beyond. The plans put forward would provide almost incalculable benefits for struggling borrowers, those whose debt is preventing them from getting ahead, buying a home, starting a business, or taking care of family. The plans also would benefit from continued scrutiny, particularly as it pertains to racial equity and durability. That this discussion is happening speaks to the issue’s importance and a renewed concern about what we owe this generation of students, borrowers, and beyond.