Summary & Key Findings

The dramatic increase in wealth inequality over the past several decades now forms the backdrop for many of today’s most pressing public policy debates. Currently, the top 1 percent of U.S. households controls 42 percent of the nation’s wealth, and nearly half of the wealth accumulated over the past 30 years has gone to the top 0.1 percent.

Simultaneously, the wealth held by the bottom 90 percent of U.S. households continues to shrink, just as people of color are a growing percentage of the U.S. population. These trends have converged to produce a wealth divide that is apparent not just by class, but by race as well. The average white family owns $13 for every $1 owned by a typical Black family, and $10 for every $1 owned by the typical Latino family.

Racial wealth inequality has its roots in historic injustices and the exclusion of communities of color from traditional avenues of building wealth — from housing, to banking, to education. Traditionally, we have viewed higher education as an antidote to inequality, but our higher education system, like so many of our institutions, is rife with racial and class disparities, from enrollment to completion.

For Black students in particular, attending college almost certainly means taking on debt in order to attain a postsecondary degree, while white households borrow less often, and in lower amounts for their undergraduate degrees. As borrowing for college has become the norm, the racial bias in terms of who must borrow to attend college and how those trends amplify already deep inequities in wealth accumulation is cause for concern.

This analysis uses the Racial Wealth Audit, a framework developed by the Institute on Assets and Social Policy (IASP) to assess the impact of public policy on the wealth gap between white and Black households. We use the framework to model the impact of various student debt relief policies to identify the approaches most likely to reduce inequities in wealth by race, as opposed to exacerbating existing inequities. We focus specifically on the Black-white wealth gap both because of the historic roots of inequality described above, and because student debt (in the form of borrowing rates and levels) seems to be contributing to wealth disparities between Black and white young adults, in particular.

Our main findings include:

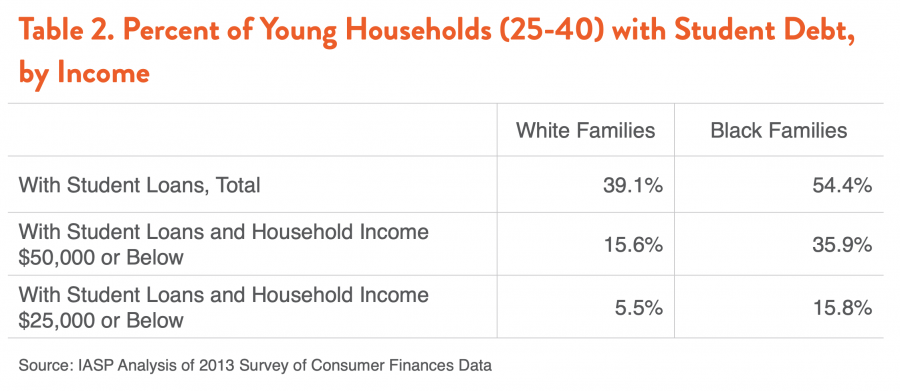

- Young Black households (ages 25-40) are far more likely to have student debt than their white peers. Over half (54%) of young Black households have student debt, compared to 39 percent of all young white households. Despite the higher earnings that often come with a degree, over a third (35.9%) of young Black households making $50,000 a year or below have student debt, compared to fewer than one-in-six (15.5%) young white households. Among those making $25,000 a year or below — around the expected earnings for those who have not completed high school— nearly 16 percent of young Black households have student debt, compared to fewer than 6 percent of white households.

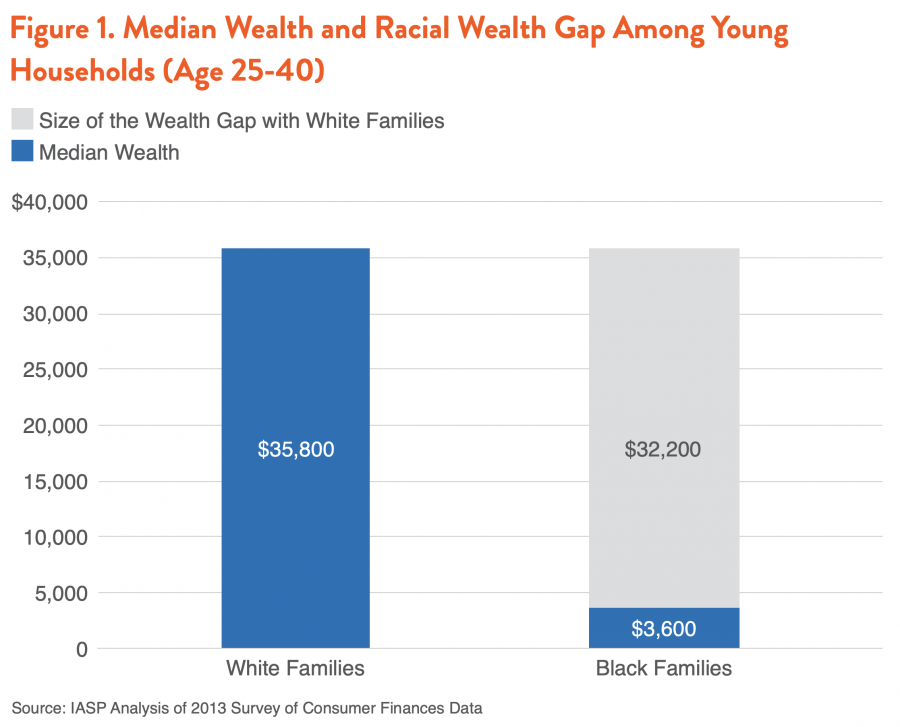

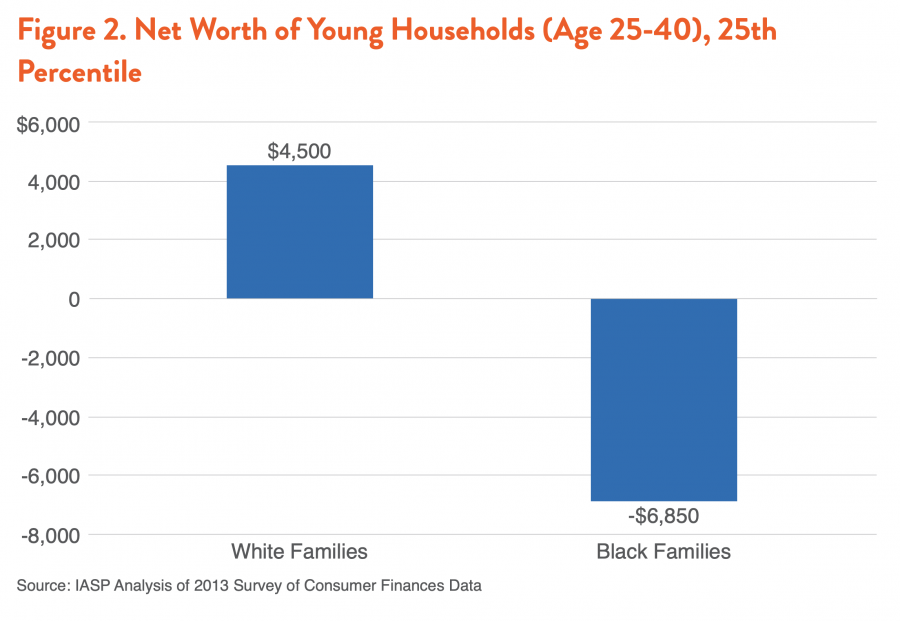

- The racial wealth gap is substantial even among young households. Among typical households age 25-40, whites have 10 times the wealth of Blacks. The net worth of low-wealth Black households (those at the 25th percentile) is actually negative, while similarly positioned low-wealth white households still have a modest financial cushion.

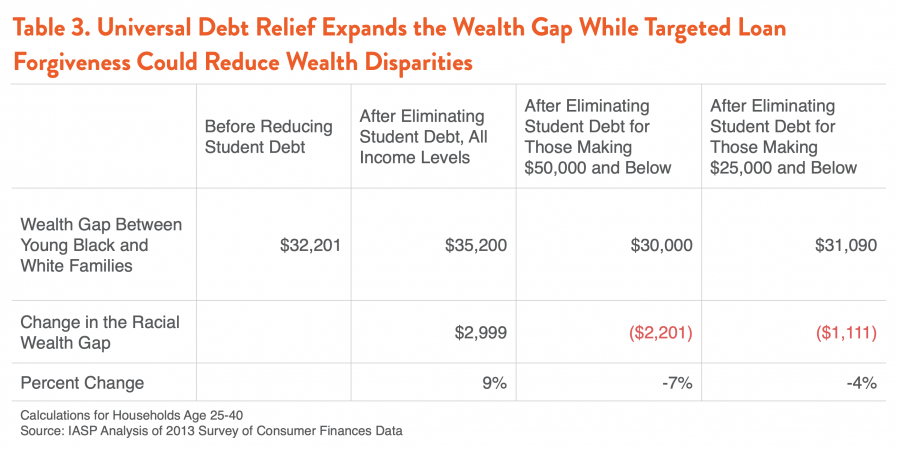

- At the median, forgiving student debt only for low- and middle-income households reduces the racial wealth gap for Black households. Eliminating student debt for households making $50,000 or below would reduce the racial wealth gap between Black and white families by over $2,000, or nearly 7 percent. Eliminating student debt for households making $25,000 or below would reduce the racial wealth gap at the median between Black and white families by over $1,000, or around 4 percent.

- A progressive student debt reduction policy would dramatically reduce the racial wealth gap among low-wealth households. While the effects of loan reduction on the racial wealth gap are modest but noticeable at the median, we see far greater effects among low-wealth households (those at the 25th percentile of wealth). Eliminating student debt among those making $50,000 or below reduces the Black-white wealth disparity by nearly 37 percent among low-wealth households, and a policy that eliminates debt among those making $25,000 or less reduces the Black-white wealth gap by over 50 percent.

- Eliminating student debt for all households would increase the racial wealth gap. While eliminating student debt for all households regardless of income increases median net worth for young white and Black households, white families see a greater benefit likely due to a higher likelihood of completing college and graduate degree programs. Policies which eliminate all student debt for young households would expand the divide between median Black and white wealth by an additional 9 percent.

These findings clearly show that policy design matters for reducing the racial wealth gap. In constructing ways to reduce or eliminate student debt, policymakers should take into account that universal elimination of student debt, while benefiting all who hold debt, might have the effect of increasing our already-expanding racial wealth divide.

On the contrary, a debt-elimination policy that targets low-income households might dramatically reduce the wealth divide, among both median as well as low-wealth households. Policymakers should take note that the same policy may impact white, Black, and other households of color differently, and adjust policies accordingly.

Introduction

Despite powerful national narratives about equality, diversity, and upward mobility, the U.S. is becoming more unequal as it has continued to become a more racially diverse nation. Wealth inequality — both the difference in wealth held by the top segment of households compared to the rest of the population, and the difference in wealth held between racial and ethnic groups — has formed the backdrop for many of today’s most pressing public policy debates. By now, the numbers are familiar: currently, the top 1 percent of U.S. households controls 42 percent of the nation’s wealth, and nearly half of the wealth accumulated over the past 30 years has gone to the top 0.1 percent of households.

Meanwhile, the portion of wealth held by the bottom 90 percent of Americans continues to shrink. Given the historical legacy of overt racism coupled with ongoing discrimination in our social and financial institutions, the growing wealth divide is sharply apparent not just by class, but by race. In fact, the average white family owns $13 for every $1 owned by a typical Black family, and $10 for every $1 owned by the average Latino family.

Racial wealth inequality has its roots in historic injustices and the exclusion of communities of color from traditional avenues of building wealth — from housing, to banking, to education. Traditionally in the United States, we have thought of higher education as an antidote to inequality, or a potential Great Equalizer in expanding opportunities for secure, well-paying jobs that lead to financial stability and the American Dream. After all, income and wealth for college graduates far exceeds that of high school graduates and those with a college education are far more likely to be employed compared to those who do not have a higher degree. In fact, the link between education and wealth has never been stronger, according to a recent analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Expanding educational opportunity, therefore, has been a central priority in U.S. public policy, but many disparities remain stark. Racial disparities permeate the educational system from pre-kindergarten through completion of post-baccalaureate programs, and inequalities at each level reflect earlier disparities and contribute to those that follow. Education, in a sense, can create a “wealth feedback loop,” as the educational level of parents significantly predicts the level of education completed by their children.

With rising college attendance but persistent and growing wealth inequalities, many have become concerned about the sharp and unrelenting rise in student debt over the past 20 years, and the impact of that debt on the ability of low and moderate resource families to accumulate wealth and financial stability in the years after college. Demos has previously analyzed the wealth of young households with student debt, finding that at every level of education, households without education debt have substantially greater wealth in both retirement and liquid savings, and are more likely to own a home. Given the higher levels of wealth among those who do not have to borrow for college and the greater need to borrow by Black students, there is reason to be concerned about the impact of student debt on household wealth and our growing racial wealth divide.

This analysis uses the Racial Wealth Audit, an analytical framework developed by the Institute on Assets and Social Policy (IASP) to assess the impact of public policy on the racial wealth gap. We use the framework to model the impact of various student debt relief policies to identify the approaches most likely to reduce inequalities in wealth between white and Black households, as opposed to amplifying existing inequities.

We focus specifically on the Black-white wealth gap both because of the historic roots of inequality described above, and because student debt (in the form of borrowing rates and levels) seems to be contributing to wealth disparities for young Black adults, in particular. While we present some analyses for Latino households later in Appendix A, the patterns of student debt burdens differ between Blacks and Latinos making distinct analyses for each group more appropriate.

Methodology & Terminology

This report focuses on analysis of nationally representative data on white and Black households in the United States. The terms refer to the representative household respondents in the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), in which respondents could identify as white and Black or African-American. Analyses for Latinos, respondents who identify in the survey as Hispanic or Latino, is also presented. Data on Asian and Native American households is not available in the SCF. Throughout this report, we use the term “racial wealth gap” to refer to the absolute differences in wealth (assets minus debt) between Black and white households as well as between Latino and white households. While the racial wealth gap is often measured at the median, we are also able to measure it at various percentiles in the wealth distribution, and report on changes at the 25th percentile in this report. All dollar figures are in 2013 dollars unless otherwise noted.

How Student Debt Exacerbates Racial Wealth Inequality

Despite its reputation as a Great Equalizer, our current system of higher education in the U.S. has served to reinforce many of the racial disparities that we see in other areas of social and economic policy. While high school graduation and college enrollment have increased among students of all racial and ethnic groups, and the differences have narrowed slightly, the gap in college completion between white students and their Black counterparts is far more substantial and has actually risen over time.

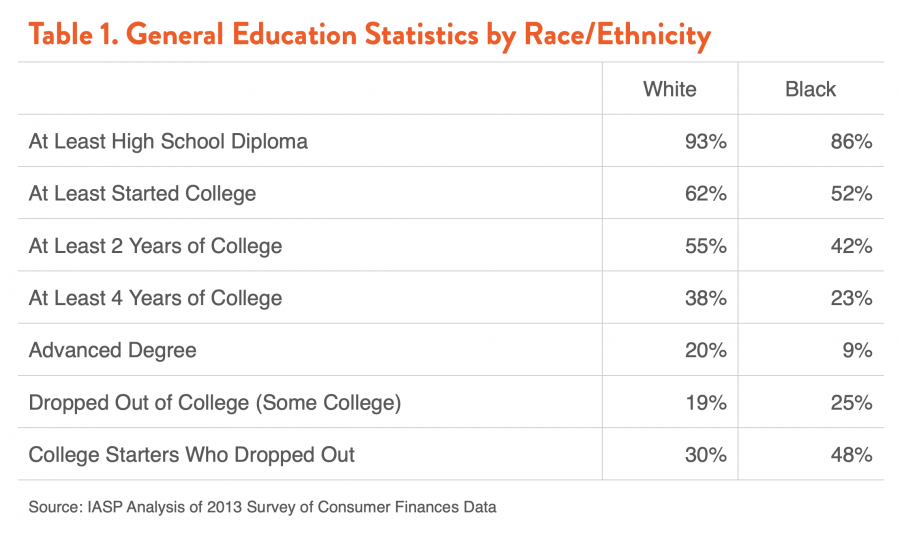

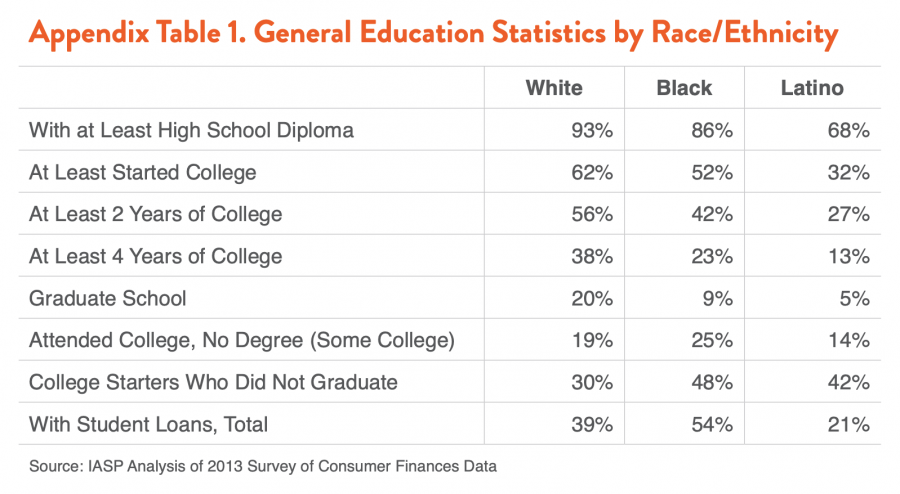

As Table 1 below shows, the differences in educational attainment between white and Black populations widen across the educational spectrum. While the vast majority of Black students graduate high school and over half at least start college, fewer than a quarter eventually get a four-year degree. As Demos has previously shown, Black student borrowers are more likely to drop out with debt. This reality has ramifications for the life course economic stability and asset-building opportunities of young, Black college-goers by limiting their ability to attain the labor market stability and subsequent wealth that a college degree confers.

Yet, despite lower rates of college completion, young Black households (ages 25-40) are far more likely to have student debt. Over half (54.4%) of all young Black households have student debt, compared to 39 percent of young white households even with the higher likelihood that white households completed college. And while modest amounts of student debt are correlated with completing college, debt amounts beyond $10,000 have a negative correlation with completing college. The rise in average debt among all students, particularly Black students, may create additional barriers to complete and receive an economic boost from a degree. With Black students already facing barriers to college completion and higher financial need for student loans in the first place, growing levels of student loans are increasingly a financial burden for young Black households.

These results also cut across income levels. Over a third (35.9%) of young Black households making $50,000 a year or below have student debt, compared to fewer than one-in-six (15.6%) young white households. Among those making $25,000 a year or below — around the expected earnings for those who have not completed high school — nearly 16 percent of young Black households have student debt, compared to fewer than 6 percent of white households.

Research from IASP has shown that the wealth gap increases with age as white families accumulate substantial wealth over the life course and Black households typically experience more hurdles, including discriminatory policies and practices, to asset-building. However, while the racial wealth gap is larger later in life, the gap starts early among young adults with white families getting a head start in their bank accounts as well as in their extended family networks.

The existence of student debt — in addition to discrimination faced by households of color in labor, housing, and financial markets — contributes to large racial disparities in wealth that show up among young households early in the life course. Even for households just getting started saving for the future, the typical young white household has nearly $10 for every $1 in Black wealth creating a head start for whites that has lifelong impacts.

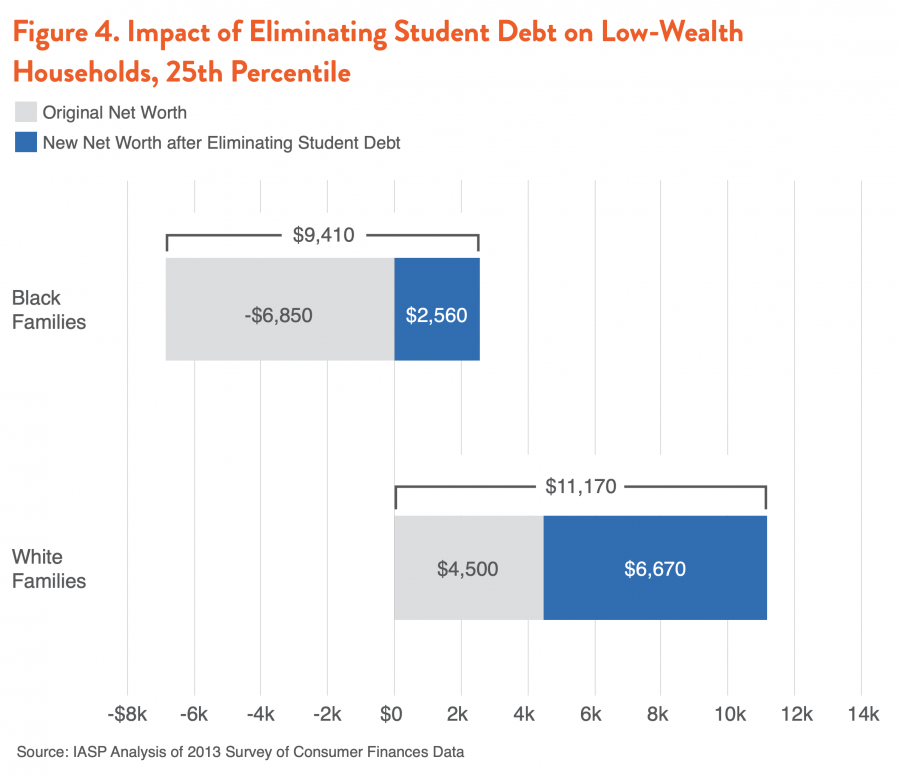

But looking at the typical household does not tell the whole story; differences are far starker among low-wealth households (see Figure 2 below). The net worth of low-wealth Black households (those at the 25th percentile) is actually negative, while low-wealth white households still have a modest financial cushion. These data demonstrate that, while among lower-wealth white households a common financial shock such as an unexpected car repair could likely be afforded with wealth reserves, such expenses would likely put a similarly situated young Black household in dire economic straits or further into debt.

Universal Student Debt Relief and Its Impact on Racial Equity

Given the higher likelihood that Black households are more financially burdened by student loans relative to whites, we utilized the Racial Wealth Audit framework to examine the impact of reducing student debt on household wealth and its subsequent impact on the racial wealth gap. We narrowed our focus to young adult households (ages 25-40), since young households are more likely to have student loans — due in part to the rising costs of college, the increasing number of young people attending college, and the shorter amount of time young people have had to pay off their debts.

Existing inequities in borrowing rates and debt levels provide a clear case for debt relief that is directed at those who are more likely to see student debt weigh heavily on their ability to build wealth. To analyze the impact of reducing student debt on the racial wealth gap, our model tested the impact on household wealth, if policy supported a one-time reduction of student loan debt among young households (25-40), at four levels: 25 percent, 50 percent, 75 percent, and 100 percent of the total student loan balance.a In other words, we tested the impact on household wealth if policies were implemented to reduce student loan balances of young adult student loan borrowers by a quarter, half, three-quarters, or entirely.

This modeling exercise allows us to understand how existing racial inequalities in wealth would change if educational policy had reduced or eliminated the need for student loans among today’s young adults, or alternatively how household wealth might be different if we did not require borrowing for higher education.

Thus, by understanding how wealth disparities would change with an elimination or reduction in existing student loans, we can better understand the role that these loans play in current wealth gaps.

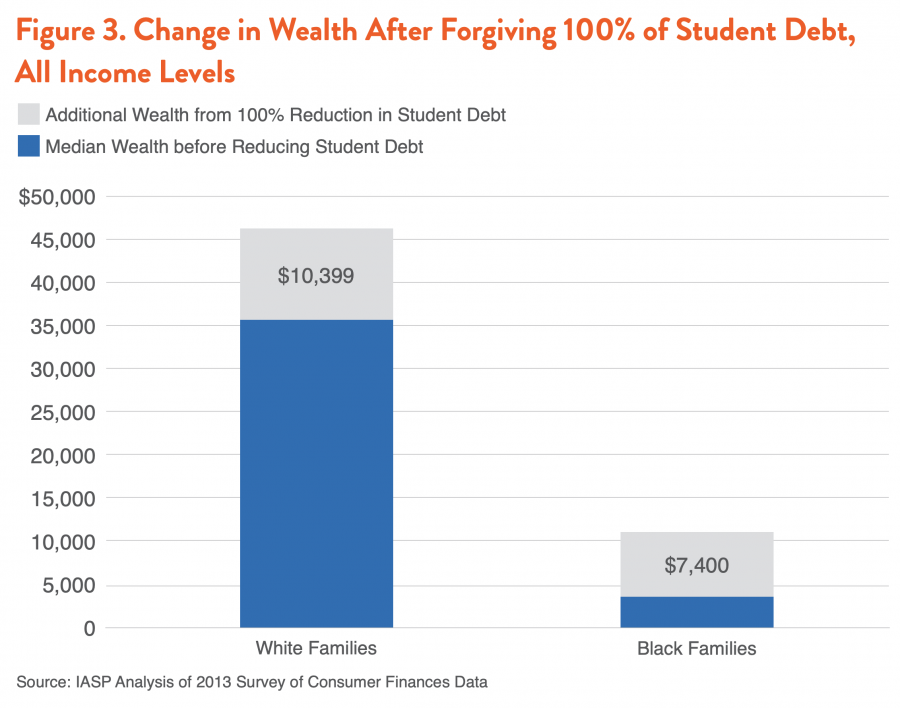

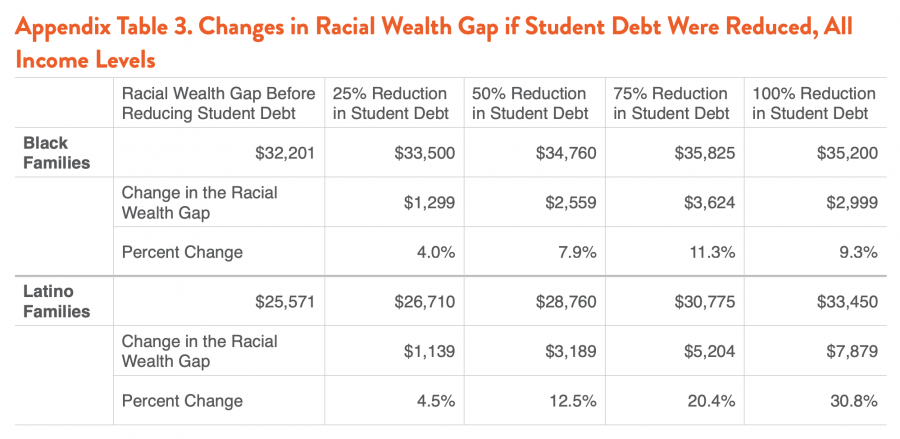

Our analysis found that, while eliminating student debt for all households regardless of income increases the median net worth for white and Black young adults alike, it also has the effect of increasing the racial wealth gap. Essentially, the typical white family would see a greater total benefit than the typical Black family (See Table 3 and Figure 4). For example, eliminating 100 percent of student debt would expand the divide between median Black and white wealth by an additional 9 percent, or nearly $3,000.

Since (as mentioned above) white households attend college— and also seek out advanced degrees — in greater numbers (see Table 1 above), they may stand to benefit more from a loan reduction policy that does not take income or financial circumstances into account. Thus, reducing student loans for all households regardless of income may actually be counterproductive in reducing racial wealth disparities, indicating that targeted relief and scholarship programs may be preferable. This finding reveals that universal debt relief may go to students with less need and more capacity to pay back loans, especially advanced degree holders who tend to have the highest incomes.

Though any debt reduction policy would serve to lower the total burden of student debt on young families, new policy initiatives should support both debt reduction and equity in reducing the racial wealth gap. Eliminating all student debt for all young adult households does not meet both of these criteria; thus, as we consider policy solutions for lowering the financial toll of student debt on young people today and decide how to direct public resources, it is important to understand that this approach does not promote equity.

However, given the finding that many Black households of modest incomes still have student debt (see Table 2 above), it stands to reason that a means-tested loan forgiveness policy may yield different results. Thus, we also tested the effects on the racial wealth gap of reducing student debt only for young households at or below median income. We tested the same loan reduction percentages for households making $50,000 (approximately the median U.S. income) and below, as well as the impact if eligibility were limited to those making half of median, or $25,000 or less annually.

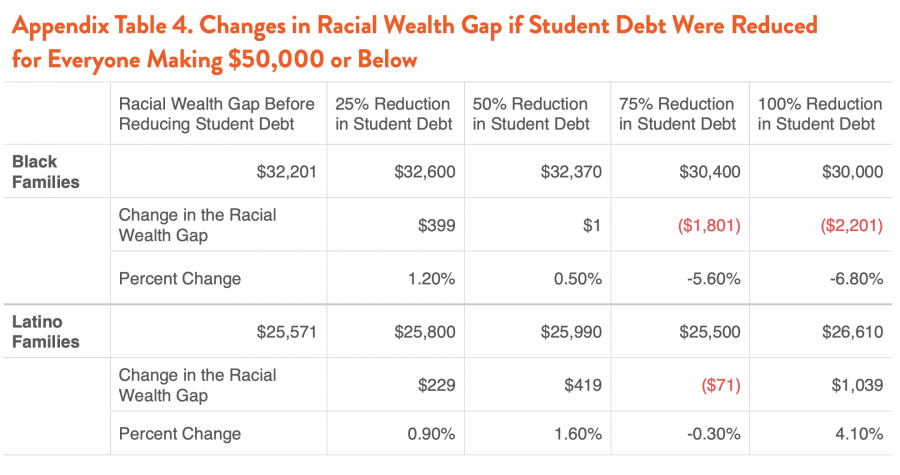

Indeed, limiting eligibility for loan forgiveness to low- and middle-income households reduces the racial wealth gap between Black and white households. The greatest reduction in the wealth gap between white and Black families occurs when families earning $50,000 or below see their loans completely forgiven. A policy of total loan forgiveness for these families would reduce the racial wealth gap between Black and white families by 7 percent, or $2,201.

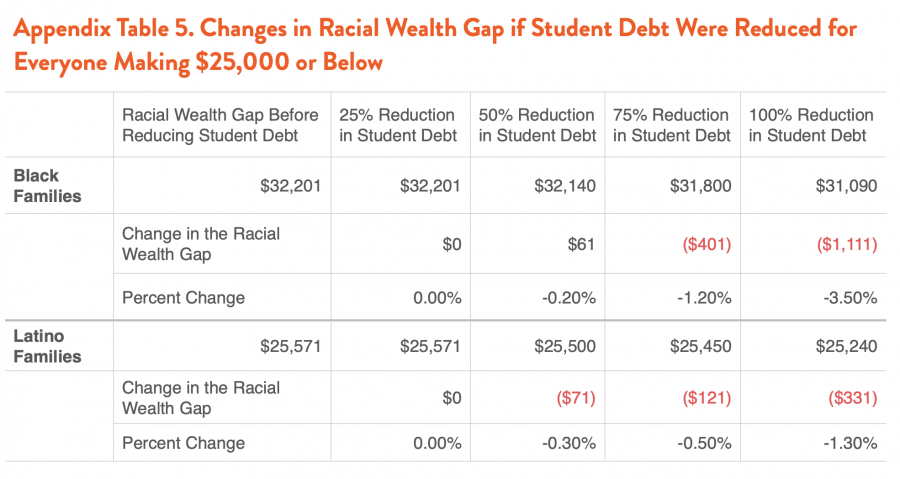

Further limiting the eligibility criteria to those making $25,000 or below also reduces Black-white wealth disparities by 4 percent, or $1,111. While these estimates may seem modest, given the numerous factors contributing to the Black-white wealth gap, a reduction of more than $1,000 in the racial wealth gap from a policy squarely targeted at those with very low incomes is quite a substantial impact.

It is also notable that we see this change in the Black-white racial wealth gap, despite the fact that a relatively small percentage of households would be eligible for such a policy. That is, fewer African Americans have incomes below $25,000, while also holding student loans compared to those with incomes of $50,000 or less, or across all levels. This makes sense; student debtors tend to have higher incomes than non-debtors in absolute terms, due to the fact that college-goers earn more on average than those who never attend college.

Yet, as mentioned above (see Table 2) Black families face a particularly high burden of student loans in each income category studied. By targeting loan alleviation programs on the lowest income student debt holders, there is an opportunity to reduce the racial wealth gap and target assistance to those with the greatest financial need.

The Impact of Student Debt Reduction on Low-Wealth Households

Given the finding that many Black families have substantial negative net worth — their debts exceed their savings and assets — we also examined the impact of loan reduction policies on the racial wealth gap among those farther down the wealth distribution —those at the 25th percentile of net worth.

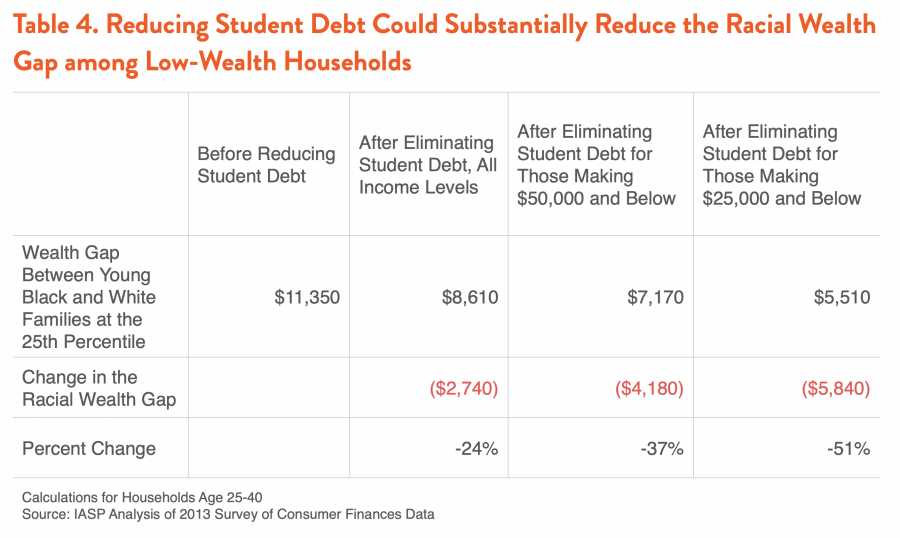

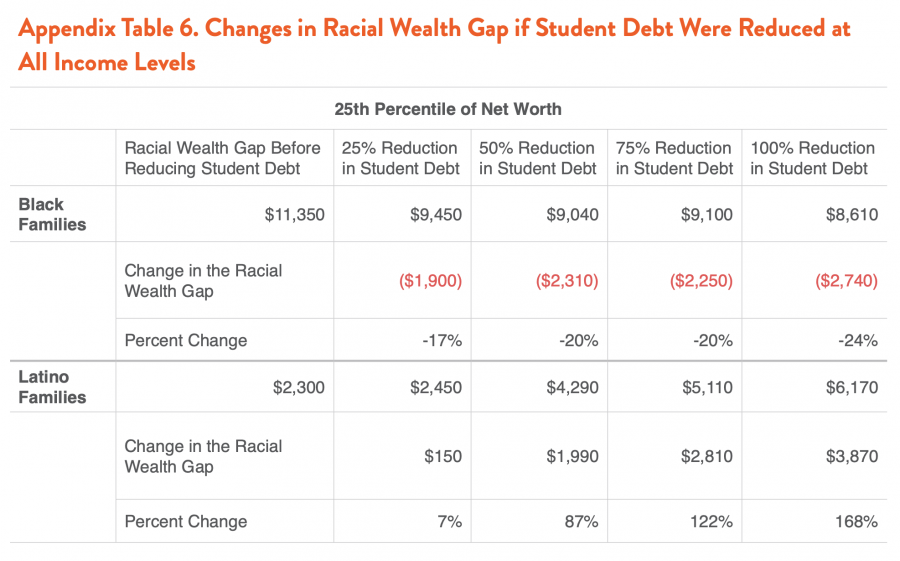

Testing the same loan reduction policies with the same eligibility criteria as seen above, we find that, while the impact on the racial wealth gap at the median was somewhat modest, yet still notable, there seems to be an even larger potential effect of loan reduction policies on the racial wealth gap at this point in the wealth distribution. For example, reducing 100 percent of student debt with no income eligibility criteria would reduce the wealth gap between Black and white families at the 25th percentile by 24 percent, or $2,740.

While a universal approach moves us in the right direction for those at the 25th percentile in terms of reducing racial wealth disparities, once more, we see that a more targeted approach focusing loan reduction efforts on lower-income households does even more to reduce the racial wealth gap among lower-wealth young households. Again, we tested the effects on the racial wealth gap of reducing student debt only for young households making $50,000 or below, and $25,000 or below, but this time examined its impact on those at the 25th percentile.

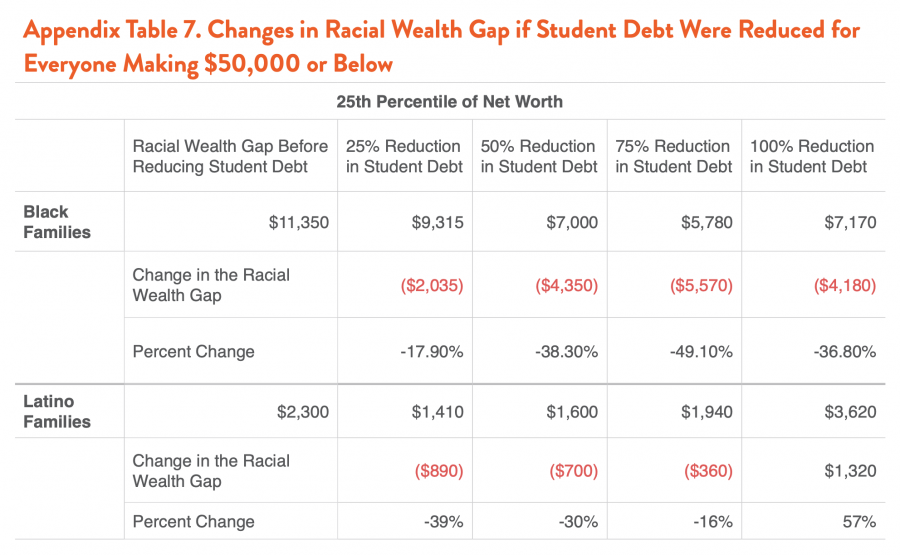

Similar to what we found at median net worth, a more progressive approach to loan reduction policy is more successful at reducing the racial wealth gap. For example, forgiving all student debt for families making $50,000 or below yields a 37 percent, or $4,180, reduction in the wealth gap between low-wealth Black and white families (see Table 4 above). Lowering the eligibility for loan forgiveness even further to those making $25,000 or less produces an even greater reduction of the Black-white wealth disparity among low-wealth households.

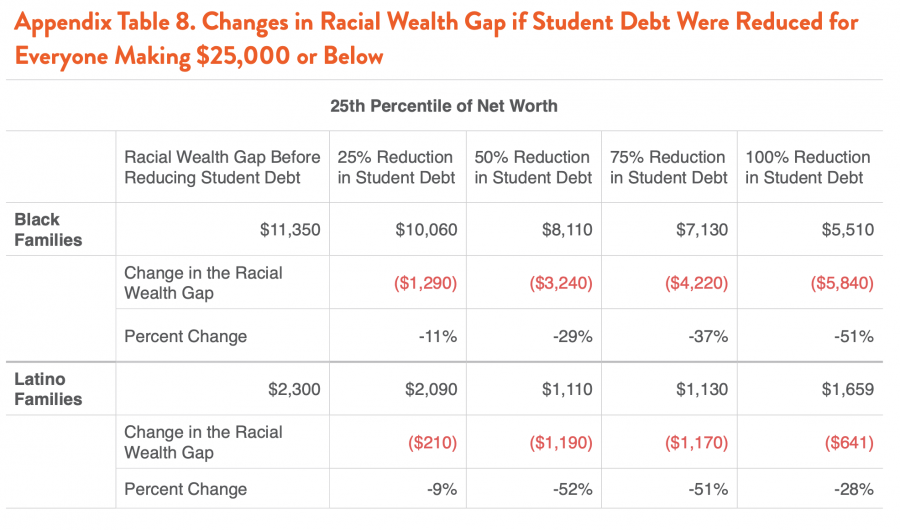

Such a policy yields a 51 percent, or $5,840, reduction in the wealth gap between Black and white families. These results are particularly dramatic. The fact that the racial wealth gap at the 25th percentile for whites and Blacks is reduced by one third to one half with a progressive elimination of student loans highlights how large a role student debt plays in racial disparities in wealth between young adults today. These results suggest that for the most vulnerable student loan debtors by income, we can reduce substantially the racial wealth gap at the 25th percentile for young Black households by developing policies which eliminate and reduce the need for low-income households to take on student loans.

Student Loan Policy Matters for Reducing the Racial Wealth Gap

These results speak to the importance of careful public policy design. If policymakers are concerned about the growing racial wealth gap as well as the growing level of educational debt among today’s young people, they should design interventions that not only reduce the overall burden of student debt, but do so in ways that do not expand existing racial wealth divides. As these analyses show, the greatest reductions in the racial wealth gap, both at the median and at the 25th percentile of the wealth distribution, come from targeted forgiveness for low- and middle-income households.

Targeted grant aid, lower tuition, and debt relief for those with tighter household budgets appeal to our sense of fairness about access to higher education, while also contributing to reductions in the racial wealth gap. By contrast, lowering debt levels and expanding assistance for all households could actually exacerbate wealth gaps by providing aid to households that have greater capacity to pay off their debts.

We know that disparities in higher education attainment and student loan burdens only account for a portion of the racial wealth gap, and policymakers should look beyond student debt to help households build wealth in the labor and housing markets in ways that reduce divides by race. However, given the substantial impact of targeted reductions in student debt on the racial wealth gap, particularly among those with lower income and wealth levels, a number of policies could be enacted that may make a sizeable difference. These include:

- Guaranteeing debt-free public higher education for low-income and middle-class households. Currently, the burden of undergraduate borrowing is disproportionately borne by low-income students and students of color. Similarly, Black students are more likely to take on loans but not complete college, which results in higher rates of delinquency and default, even with relatively low loan balances. Providing a guarantee of debt-free public higher education in a way that targets subsidies toward those who are most likely to face unmet financial need for college could increase both college attendance and completion rates, while having the effect of eliminating borrowing for most students of color.

- Institutional accountability and debt forgiveness for students attending low-quality institutions. Many students face trouble repaying student loans due to attending a college that required borrowing but provided specious value in the labor market. Students at these institutions, many of which reside in the for-profit college sector, often have very little recourse to have debt forgiven, even in instances of fraud and abuse. A mechanism of loan forgiveness for these students would target those who need forgiveness the most — frequently low-income and students of color. Tighter oversight of colleges and degree programs, including the strengthening of Gainful Employment regulations, would also ensure that these institutions’ access to federal financial aid and loan dollars are restricted, and that students enter a fairer higher education marketplace.

- Incremental debt forgiveness for students in public, low-wage professions. Currently, the federal government provides loan forgiveness for those who work in public service professions for 10 years, and have made 10 years of payments on their student loans. This benefit, Public Service Loan Forgiveness, aligns debt reduction with those whose incomes are low enough as to be unable to pay off their loans in that timeframe. That said, the program does not have an income eligibility criterion and is scheduled to provide a substantial portion of forgiveness to graduate degree holders, many of whom have above-average incomes. Low-wage public service workers with undergraduate debt are less likely to see the same type of benefit, in many cases because their loan balances are far smaller. Ensuring that those who work in low-wage public service professions, including social workers, teachers, educators, and first responders, also receive forgiveness, perhaps by providing a reduction incrementally rather than at one time after 10 years, has the potential to reduce the racial wealth gap by targeting those with lower incomes.

- Allow student loans to be discharged in bankruptcy. Unlike other forms of consumer debt, student loans are extremely difficult to be discharged in bankruptcy. Those seeking to discharge student loans must satisfy an onerous and ill-defined “undue hardship” standard, in some cases effectively making it impossible to discharge loans even in the most hopeless of financial circumstances. The barrier is so high that 99.9 percent of individuals with student loan debt who file bankruptcy do not even bother to allege an “undue hardship.” Reforming our bankruptcy code’s treatment of student debt would, by definition, provide loan forgiveness and reduce debt to those who face the greatest financial hardship, and thus, has the potential to reduce the racial wealth gap.

Appendices

Appendix A: Latino Student Loan Debt and the Racial Wealth Gap

While this analysis focuses primarily on differences in Black-white wealth, we also examined the impact of student debt reduction on young Latino households. Our findings confirm that the patterns of student loan debt and barriers to educational access differ between Black and Latino students making distinct discussions of the key student debt concerns appropriate. According to data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Latino households attend and graduate from college at lower rates than both Black and white households. Our analyses also point to the much lower household wealth levels among Latinos relative to white families. Likely due to lower rates of college attendance and attainment, the percentage of Latino households with student debt (21%) is lower than that of both Blacks and whites. Thus, the dynamic of student loans is different for Latinos than that seen among Black households, who despite lower college attendance and completion rates than whites, are far more likely to hold debt.

Evidence also suggests that Latino students may be more adverse to taking on student loans even when they face substantial financial need for school, and Demos has found that while Latino students tend to borrow less than Black and white students at public institutions, they borrow at comparable — or even higher — amounts at private for-profit institutions, where they also drop out with debt at high rates.

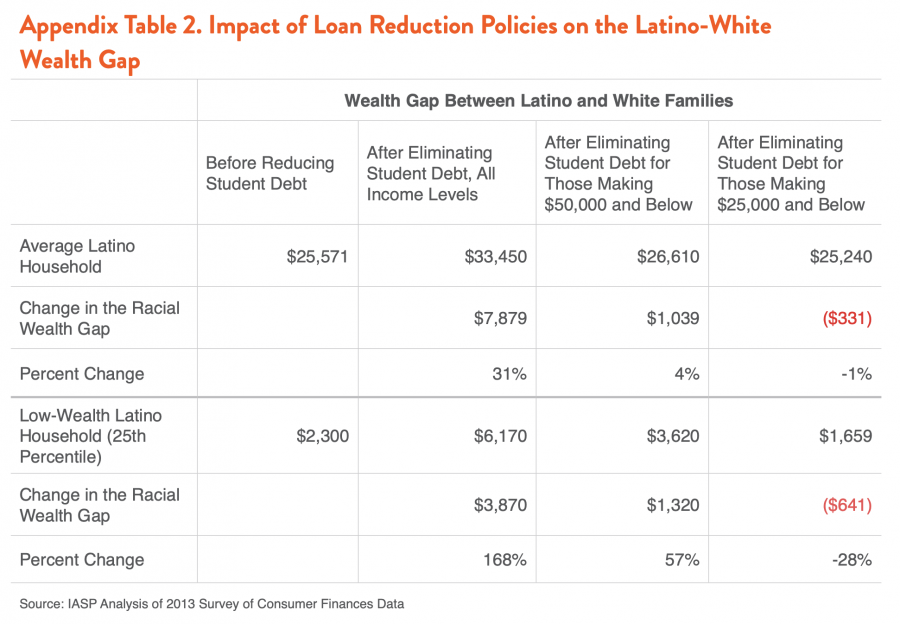

Our model suggests that loan reduction policies may play out differently for the Latino-white wealth gap (see Table 6), perhaps due to differences in educational attainment (see Table 5). Universal debt reduction policies would benefit Latinos modestly but would expand the racial wealth gap among both typical and low-wealth households, even when the policy is targeted squarely at borrowers making $50,000 and below.

Again, this is not because loan reduction would reduce Latino wealth per se, but rather that white families see a larger benefit than Latino families in this scenario. However, a loan reduction policy targeted at those making $25,000 or below would reduce the racial wealth gap at both the median and among low-wealth households, though the reduction is less than that seen for Black-white wealth differences. We posit that these results stem in large part from the fact that the lowest wealth Latino households face numerous barriers to higher education making them less likely to begin college and take out loans.

Appendix B: Modeling Student Loan Reduction Policies on the Racial Wealth Gap