Introduction

Arizona has a proud tradition of affordable public higher education. In fact, written in the state constitution is a promise that, at public colleges, “the instruction furnished shall be as nearly free as possible.” The Grand Canyon state boasts a large system of public 2- and 4-year schools—institutions that engender state pride and drive local and regional economies.

Today, over 460,000 students attend Arizona’s public colleges and universities. Over half—nearly 280,000—are enrolled in Arizona’s community college system. For each of these students, postsecondary education is a key step in achieving their professional and personal dreams and hoping to guarantee some financial stability. And yet policymakers in Arizona have made this step harder, through continuous divestment in Arizona’s public higher education system, resulting in skyrocketing college prices. This has coincided with record increases in the cost of living in parts of the state, as well as the rising cost of childcare and other necessities upon which all families rely. As a result, today over 840,000 Arizonans hold more than $29 billion in federal student loans.

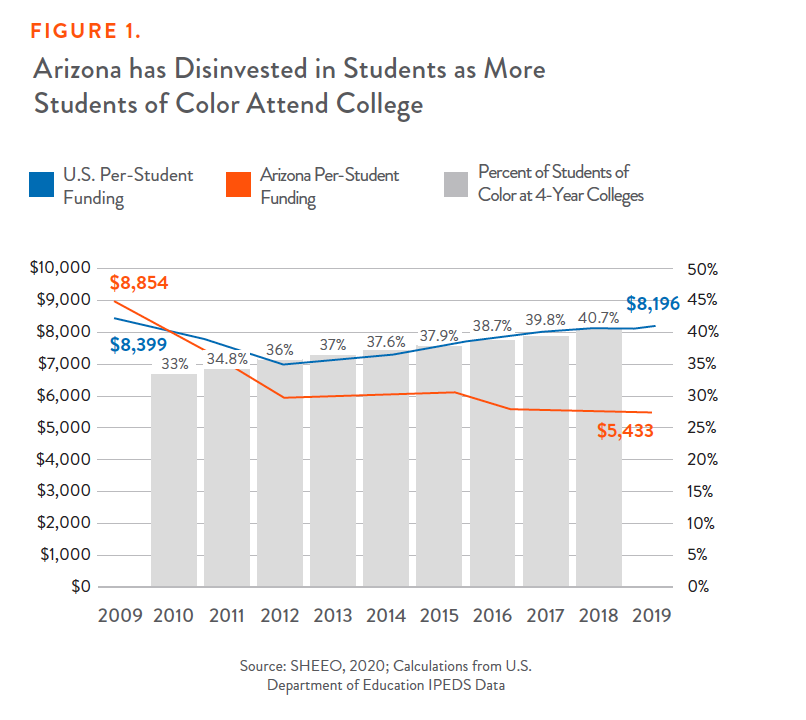

The soaring costs and shrinking state support have taken place as the very face of the Arizona college student has changed. The percentage of students of color at Arizona’s public 4-year colleges has increased from 33 percent to 40 percent over the past decade alone. During the same time period, policymakers have seen fit to cut per-student funding by nearly 40 percent. For policymakers obligated by the state constitution to make college affordable, reversing these deep funding cuts is a first step to ending the affordability crisis—particularly for the state’s Black and brown students, who face greater financial burdens from racially unjust housing and labor markets.

The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic crisis has upended Arizona’s budget and forced hard conversations around what the state should do to secure families’ finances. The pandemic has hit Black, brown, and Native Arizonans particularly hard, and exposed the deep economic and public health divides facing the state. Lawmakers need to do everything in their power to help families weather this crisis, by assisting those experiencing unemployment, housing and food insecurity, and uncertainty about their future. At the same time, Arizona’s policymakers must not take this as an opportunity to saddle institutions, families, and students with deeper cuts and higher college costs, all of which take a greater toll on Black and brown families and communities. Doing so would only increase student debt for some and close the doors of educational opportunity for others who feel that the cost of attendance is out of reach. It will make the recovery longer and more difficult and move Arizona further away from the goal of building an inclusive economy.

Coming out of the recession, Arizona has an opportunity to make good on the promise embedded in the state’s constitution for the most diverse generation of students in its history. The federal CARES Act was a preliminary effort to help Arizonans hold on through the crisis and stay in their homes, and help colleges backstop some funding cuts. Congress allocated funds to Arizona colleges based on both the full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment and the FTE enrollment of Pell Grant recipients (a proxy for low-income students), and also allowed student borrowers to pause their debt payments through the current crisis. Yet the funding was insufficient to fully prevent budget cuts, and the economic recovery is likely to be slow. Additional federal support finally committed in late 2020 will not meet the need. Students facing a rent crisis, food insecurity, or a debt burden that still must be repaid are in desperate need of help from Arizona’s lawmakers for as long as Congress continues to provide insufficient and lagging support.

And as the movement for free or debt-free college sweeps across the country, including in neighboring New Mexico, Arizona cannot afford to fall further behind in investing in the state’s talent, workforce, or people. Making such an investment will require tackling the direct cost of college and reducing (or even eliminating) tuition and fees, but it will also require recognizing that these are but one part of the college affordability puzzle. Families still need to pay rent for themselves and their children, pay for childcare each month, and work their way through school. A guarantee of debt-free college must include bold policy that ensures anyone who wants an education is not forced to drop out or take on debt to pay for these basic expenses.

More Students of Color Seek Opportunity

Just over a decade ago, Arizona’s per-student funding of public higher education was higher than the national average. Arizona invested $8,854 per student in 2009, compared to just under $8,400 across the United States. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, though, Arizona’s lawmakers took a hatchet to higher education funding and continued to do so through the economic recovery. Arizona now ranks 46th out of 50 in per-student appropriations. This rapid descent in public funding has coincided with an increase in the number of students of color attempting to access college. At Arizona’s public 4-year schools, students of color made up one-third of those enrolled in the fall of 2009, and now make up over 40 percent. Just as non-white students began seeking opportunity in greater numbers, Arizona’s lawmakers decided not to extend the same investment as previous generations enjoyed (see Figure 1).

Unsurprisingly and unfortunately for this generation of Arizona students, tuition has increased and now makes up a far greater portion of overall college funding, as Figure 2 shows. Whereas tuition funding made up 38.7 percent of Arizona’s educational appropriations in 2009 (roughly in line with the national average), it now makes up nearly two-thirds (62.7 percent). What was once a public good, funded primarily through state and local appropriations, is now primarily paid for by students themselves.

In other states, students can often hope to counteract tuition expansions with state financial aid that can defray the cost of higher education. But Arizona has no student aid to speak of, as Figure 3 illustrates; on average, states spend $808 per full-time student per year in financial aid (which students can add to Pell Grants and other institutional scholarships to reduce their debt burden). For Arizona students, that number is $39, less than the cost of one textbook.

Arizona’s Affordability Crisis is Growing

Due to disinvestment, a lack of grant aid, and the rising cost of living, Arizona’s students face a steep hill in paying for college. The average net price of college—the total cost of attendance minus any grant and scholarship aid—at Arizona’s public 4-year colleges is over $12,735, an increase of nearly $3,000 a year over the past decade (see Figure 4). For students from low-income households (earning under $30,000 a year), the annual burden is over $8,500, an increase of more than $1,600 over 10 years’ time. Multiplied over 4 years, it becomes nearly impossible for poor and working-class Arizonans to pay for public college without taking on loans.

At Arizona’s community colleges, ostensibly the affordable or “nearly free” option, students still face high net prices, as Figure 5 indicates. While tuition averages just over $2,000 a year at Arizona’s community colleges, the average student and the average low-income student both owe more than $7,000 a year to attend a public 2-year school once all other expenses are factored into the equation. In other words, Arizona’s lawmakers cannot assume community colleges are easily accessible and affordable based on tuition alone.

Unequal and Unaffordable for Black and Brown Families, Native Families, and Single Parents in Arizona

Skyrocketing college prices harm all families and betray the promise of higher education as a public good. But as with so much in Arizona’s economy, college costs place a particular burden on Black and Latinx families who faced structural racism in the labor market, housing discrimination, and other economic headwinds well before the recent pandemic and recession. For white non-Hispanic families, the average net price of college takes up a sizeable percentage of typical household income: nearly 19 percent. For Black and Latinx families though, the net price of college equals over 24 percent of a typical household’s income. For American Indian families, college prices take up nearly a third of all annual income. And for single mothers, college prices make up nearly 40 percent of a year’s earnings (see Figure 6). Combined with the rising cost of childcare and other necessities, this makes college without debt effectively out of reach.

The COVID-19 Economy Worsens the College Affordability Crisis, and the College Affordability Crisis Worsens the Recovery

Arizonans are facing a new and often horrifying economic reality since the COVID-19 epidemic and the ensuing economic downturn. As Arizona struggled to contain the virus throughout the summer of 2020, families faced a public health disaster and economic precarity for which they could not possibly have prepared. The impact on Arizona families—especially Black, Latinx, and Native families—has been well-documented, worsening what was an already unequal economy.

Before the pandemic, renters across the state faced a growing burden in terms of paying rent, as Figure 7 illustrates. In many Arizona cities, families were facing a rent crisis: in Tucson, for example, over half (53 percent) of renters were “cost-burdened,” or paying more than the recommended 30 percent of income on rent. In Phoenix, home to the fastest-rising rents in the nation, nearly half of all rental households reported being cost-burdened.

Naturally, the recession has threatened to deepen this housing crisis, and in so doing turn higher education from a burden to an impossibility. In September 2020, 1 in 10 Black Arizona renters and 1 in 8 Latinx renters reported being behind on rent payments. Nearly 1 in 6 Black Arizonans reported experiencing at least some food scarcity as well (see figure 8).

Obviously this is the result of a labor market being upended, and circumstances may yet get worse for many families. A staggering 52 percent of Latinx Arizonans and 60 percent of Arizonans age 18-24 reported a loss of income since March—and 27 percent and 31 percent, respectively, reported an expectation that they would lose income in the next 4 weeks, as Figure 9 shows.

This is a crisis for all Arizona families, not just students or those who plan to send their children to college. However, addressing these basic needs has important and long-lasting implications for Arizona’s higher education system. Traditionally, college-going increases in recessions, as jobs become scarce and many workers return to school to retool their skills or learn a new trade or discipline. But with Arizona facing an $800 million budget shortfall, and so many families losing access to basic needs, colleges may experience less funding and uncertain demand. Further, the more that families have to pay out of pocket or go into debt for an education, the fewer resources they will have to spend or save elsewhere, thus contributing to a slow recovery. In other words, families are in a no-win spot: put their educational dreams on hold because of the economy, or face higher costs and greater financial uncertainty on the other side of the crisis.

Indeed, COVID-19 is upending the higher education plans of many Arizona families (see Figure 10). Nearly half of all families where at least one person expected to take college classes in the fall of 2020 reported that classes had either been cancelled or their course loads reduced. Some of these students will return to college; others will not. A drop in enrollment in Arizona’s colleges not only harms students, but puts community colleges—which have seen a precipitous drop in state and local funding, and are more likely to enroll poor and working-class students and students of color who may need extra financial support during the pandemic—in an even more precarious financial spot.

Arizona Lawmakers Cannot Continue to Cut Higher Education and Must Make a Down Payment on Debt-Free College in 2021

Early in 2020, Arizona lawmakers were discussing how to allocate a budget surplus, yet due to the economic crisis, they are now presented with an uncertain budget picture in an economy where families face tattered finances and a need for relief. Recent estimates suggest that the economic fallout from COVID-19 will result in a 7-8 percent budget decline in Arizona this year. Given this, it may not seem like a time to focus on debt-free college in Arizona. And yet, given the years of disinvestment and the needs of Arizona’s students—particularly the growing proportion of students of color—it is vital that lawmakers consider a major down payment on college affordability.

While overall fall college enrollment is down slightly in Arizona due to the unique factors of the pandemic, we know from previous recessions that the ranks of those going to college will likely increase if broad economic pain lingers and jobs remain scarce. With families, particularly Black, brown, and immigrant families, digging out from under an economic collapse for which they had no way to plan, the idea that college prices will simply continue to grow is both cruel and counterproductive.

In the spring of 2020, a full 58 percent of college students, including 71 percent of Black students, reported insecurity in addressing basic needs such as food and housing, according to a report from the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. Making a down payment on affordable or debt-free college now would help the long-term economic outlook in Arizona while addressing the current crisis facing students.

Policy 1: First-Dollar Free College

Arizona lawmakers should increase funding to public 2- and 4-year institutions through a “first-dollar” free college program, in which the state eliminates tuition and allows students to use any grant or scholarship aid on living expenses and other non-tuition costs. Nearly 20 states have a free college program, though many programs only offer funding once students have exhausted financial aid, and do not cover costs beyond tuition. Lawmakers in Arizona have an opportunity to create a truly comprehensive and progressive model that can be scaled up as budgets rebound. They can start by eliminating tuition up front and allowing Pell Grants and other aid to be used to defray the costs of housing, food, childcare, and other essentials—and by focusing this program on working-class students most affected by COVID-19, students attending community college or colleges that enroll high numbers of Black and brown students, as well as frontline and essential workers and their families (as other states have begun to do.) As budgets return to normal, and ideally once the federal government has backstopped state and local governments, such a program could be expanded to include more students.

This approach is equitable and generous: all eligible families would receive the benefit of $0 tuition, while those receiving the federal Pell Grant can use funds to pay rent, childcare, books, and transportation costs that might otherwise put even a tuition-free college education out of reach.

Policy 2: Increase State Aid, Including Emergency Aid to Students

As mentioned, Arizona spends just $39 per student on grant aid, and the average net price of college for low-income Arizona students is over $8,500 a year, showing that even after demonstrating financial need and receiving grant aid, students face considerable costs. Crucially, Arizona lawmakers must increase state need-based aid through the Arizona Financial Aid Trust Fund and other sources, all of which have been underfunded for years.

Through the CARES Act passed by Congress and signed into law in March 2020, Arizona institutions received funding for emergency financial aid for students facing economic costs of COVID-19. Arizona State University, the University of Arizona, and Northern Arizona University received $32 million, $15 million, and $11 million, respectively, through this fund, while large community colleges such as Glendale Community College and Mesa Community College received between $3 and $4 million each for students. These funds were necessary—if likely insufficient—to help students make up for a loss of income, housing or food insecurity, or other unexpected costs related to COVID-19. For example, Eastern Arizona College used funding for $600 grants to students, a helpful start but likely not enough to make students completely whole.

While the funds come from a federal program, and additional federal support is desperately needed for vulnerable students, Arizona lawmakers should establish a state emergency aid fund for students beginning in 2021. Given the financial precarity facing Black, Latinx, and Native Arizonans, and the likely event that any economic recovery will be slower for families of color, a robust emergency aid fund will help families tap resources in future years as the job market continues to be shaky.

Policy 3. End Disparities in College Funding and Encourage Inclusion at Larger Public 4-Year Schools

When providing a guarantee of debt-free college, or expanding aid to students, Arizona lawmakers should consider historic disparities in funding between community colleges, regional colleges, and larger, well-resourced institutions. In designing any program, Arizona should first look to provide greater subsidies for community colleges, open-access 4-year colleges, and public Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs).

Simultaneously, Arizona needs to ensure not only that the institutions that enroll the lion’s share of working-class students and students of color be able to provide a low-cost education to students, but also that new investments are made through a reparative lens. For example, Black and Latinx students are underrepresented at both the University of Arizona and Arizona State University.

Any affordability promise to larger institutions like the University of Arizona and Arizona State could include a mandate that they take steps to enroll a more economically (and ideally, racially) diverse student body, or that they contribute a portion of endowment or other funds to providing need-based aid to underrepresented groups as a condition of their commitment.

Policy 4: Keep Families in Their Homes and Offer Rent Relief

Students cannot hope to learn, particularly in an age of online and hybrid courses, without a roof over their heads. While Arizona Governor Doug Ducey extended a moratorium on evictions through October 2020, families—many of whom were rent-burdened before this crisis—are now staring down the burden of housing costs like never before. It is not enough to offer a halt to evictions. Arizona must offer real rent relief and affordable housing for all families, especially those hoping to attend school. While there has been modest relief for Arizona renters, applications remain backlogged and evictions are still occurring: in Maricopa County, despite some rental relief and a COVID-19 eviction moratorium, over 10,000 families have been evicted since March 2020.

Lawmakers must also invest in the Arizona Housing Trust Fund, which helps finance affordable housing construction and assists vulnerable communities to afford rent and stay in their homes. In 2007, Arizona committed over $40 million to the Housing Trust Fund, and despite a few recent increases in funding, it stands well below its pre-recession peak. Arizona lawmakers need to address the affordable housing crisis for all families. For students, affording a home can mean the difference between staying in school and dropping out, and some families take on student loans just to keep their families from losing a home.

Policy 5. Bold and Targeted Loan Forgiveness and Protection for Current Borrowers

While most student debt comes in the form of federal loans, there is nothing stopping states from addressing the burden of student debt for their residents. Arizonans hold $29 billion in federal student loans—and while borrowers were exempt from making payments through the end of 2020 due to the CARES Act and an executive order from the Trump administration, that debt will still be on the books awaiting repayment when the federal government deems the economic crisis to be less of a worry.

Arizona should consider canceling a portion of debt for residents who attended college in the state. A one-time debt payment—of $5,000 per borrower, for example—would work to jump-start Arizona’s economic recovery. It would also eliminate debt for those with relatively low balances, or those who have taken on debt but not graduated, who research suggests are exceedingly likely to default on a loan.

Additionally, many states, including neighboring California, have begun experimenting with worthwhile protectionary measures for student borrowers. Some efforts, such as creating a Student Borrower Bill of Rights, are aimed at expanding oversight of loan servicers operating within a state, reviewing borrower complaints, compiling data on student debt, and empowering attorneys general to bring cases on behalf of students who see their payments mishandled or are otherwise misled by their loan servicer.

It’s Time to Invest in Arizona’s Students

Embedded in the state constitution is a belief that the more Arizona puts into its people, the more it gets back. The state once committed to an affordable or “as free as possible” education for families, but broke that promise when Black, Latinx, and Native families began knocking on the doors of Arizona’s colleges and universities. Today, right when a college degree is more important than ever, and as families face an economy more uncertain than any in recent memory, Arizona’s leaders have backtracked on commitments for public colleges. And in fact, going to school is even harder to do given the cost of rent, childcare, and other necessities. It’s time to recommit to policies that help families thrive, that built world-class public colleges for all Arizonans, that allow everyone to get a degree without going into debt or going broke trying to avoid it. We need to ensure Arizona is a state where families can dream big, develop their potential, and realize their greatest aspirations—and that means making public 2- and 4-year colleges truly affordable to everyone.