If the twin threats to public pensions continue, African American retirees may lose much of the retirement security they’ve gained over the past half-century.

Public sector jobs, with the pensions they provide, have been one of the most important ways for black families to enter the middle class since the 1960s, when civil rights legislation and the expansion of the federal government opened the door for African American workers to enter public service. In particular, the establishment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was responsible for enforcing workforce anti-discrimination provisions in the Act, and President Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order 11246, which prohibited government contractors from discriminating on the basis of race and other categories, created opportunities for black workers to enter civil service en masse. Between 1961 and 1965, black workers were hired for 28 percent of new positions in the federal government despite comprising just 10 percent of the U.S. population. The importance of public sector employment for African American workers has continued to the present day, with 21.2 percent of all black women and 15.4 percent of all black men working in the public sector, compared to 17.5 percent and 11.8 percent of white women and men, respectively.

Despite decades of efforts to reduce employment discrimination in the private sector, public employment remains important to African American workers as a source of income security, helping to close the wage gap between white and black workers. In 2014, black private sector workers earned just 78 percent, on average, of the wages of their white counterparts. In the public sector, however, this gap was significantly smaller: black public sector workers earned 90 percent of the wages of white public sector workers. Even when broken down by education level, the earnings gap between black and white workers was smaller in the public sector for workers of all levels.

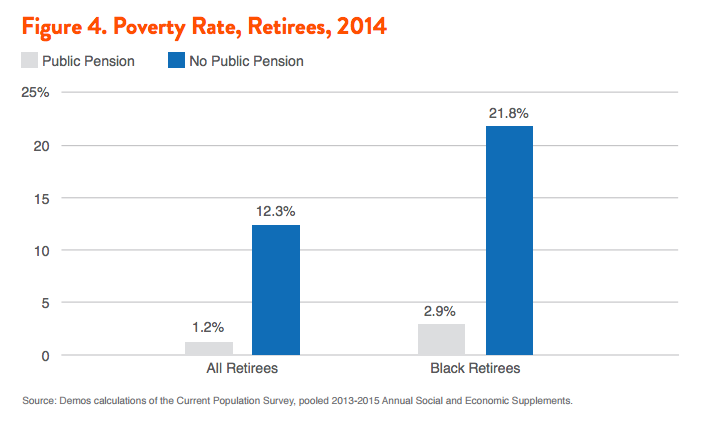

As important as public employment is to the black middle class, the pensions provided by public employment are perhaps even more crucial to the retirement security of black workers. This brief uses data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement to examine the importance of public pensions to black retirement security, and why the twin threats to public pensions—cuts to state pension benefits and the decline in public employment over the past two decades—particularly threaten the retirement security of African American workers. We find that public pensions are vital to ensuring a decent standard of living for black retirees: the poverty rate among black retirees without public pensions is nearly 20 percent higher than the poverty rate among black retirees with public pensions—almost double the difference in poverty rates between all retirees with and without public pensions. These figures show that if the twin threats to public pensions continue, African American retirees may lose much of the retirement security they’ve gained over the past half-century.

Public Pensions and Black Retirement Security

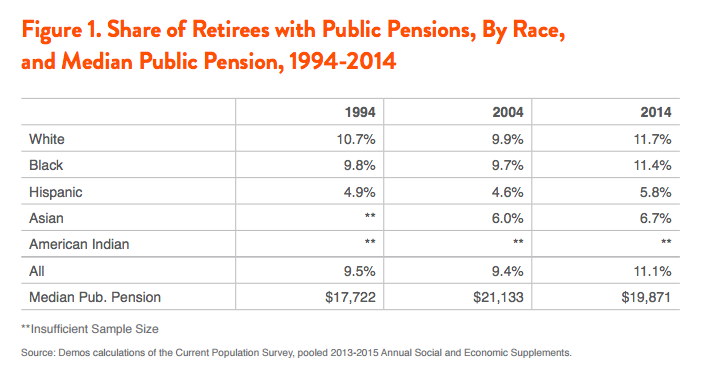

Over the past twenty years, many of the African American workers who entered public service during the boom in black public employment in the middle of the last century have begun to retire. As Figure 1 shows, over the past two decades the share of black retirees with public pensions has increased sharply as well, from 9.8 percent to 11.4 percent, mirroring the rise in the overall share of retirees with pensions. The median pension has also risen, increasing more than 11 percent since 1994. Looking by gender, smaller shares of retired women of all races have public pensions than do men; women’s pensions are smaller than men’s as well, though both gaps have narrowed in the past two decades. The share of retired black women in 2014 with public pensions, 11.7 percent, has caught up to the share of black male retirees with public pensions, 11.0 percent, up from 8.9 percent and 11 percent, respectively, in 1994.

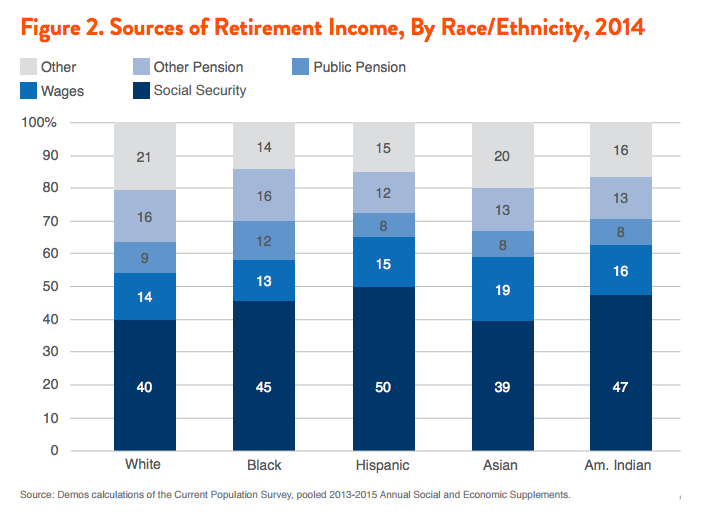

Public pension income is particularly important to African American retirees, providing a larger share of income for them than for retirees of other races and ethnicities. Figure 2 depicts the shares of retirement income that retirees receive from five major income categories: Social Security, wages, public pensions, other pensions (including defined contribution plans and private defined benefit plans), and other income (including income from interest, dividends, businesses, farms, and rent). It shows that in 2014, public pensions and Social Security together accounted for 57 percent of black retirees’ income compared to 49 percent for white retirees. By gender, Social Security accounted for a far larger share of the retirement income of women of all races in 2014 than it did for men; conversely, other pension income made up a smaller share of women’s retirement income than it did men’s. Social Security and public pension income is particularly important for black women: together, the two income sources accounted for 63 percent of the total retirement income of black women, the highest share of any race and gender; black men, in comparison, received 51 percent of their income from the two sources combined.

Figure 2 also illustrates another important trend: the increasing share of retirement income provided by wages for all retirees. Between 1994 and 2014, the overall share of retirement income from wages increased from 3 percent to 15 percent, due to the increasing number of older Americans who continue to work after taking Social Security. Although many of them are in the upper half of the income distribution, many Americans in the bottom half of the income distribution are working past age 65 as well. Various factors drive this trend of older and post-retirement work, but the biggest contributors are the increase in the Social Security Full Retirement Age from 65 to 67, the decline in labor force participation of younger Americans (largely because of increased pursuit of higher education), delayed family formation by younger Americans, and the decline of private pensions—each of which has either forced or incentivized older Americans to work longer.

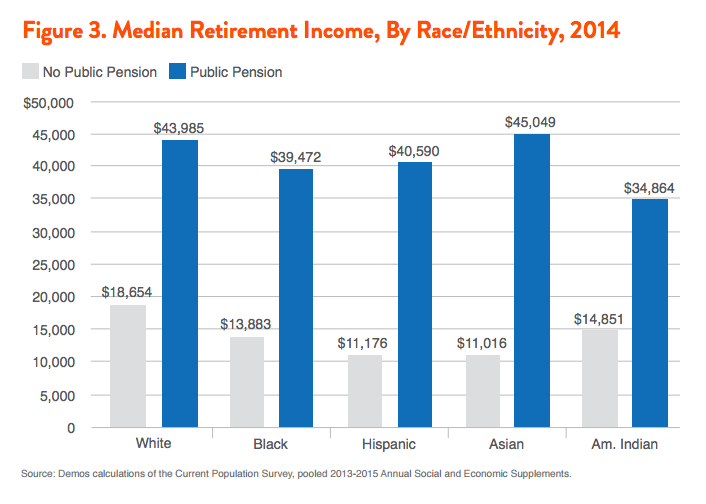

Examining the incomes and poverty rates of retirees with and without public pensions provides the most striking evidence of black retirees’ reliance on public pensions. Figure 3 shows that the median income in 2014 for retirees without public pensions was near or below the individual poverty line ($11,367 a year in 2015) for retirees of any race, because the majority of retirees without public pensions rely on Social Security for nearly all of their retirement income. For African American retirees and other retirees of color, a public pension is literally the difference between a secure retirement and one spent in or near poverty.

The importance of public pensions to black retirement security is perhaps mostly starkly illustrated by the huge difference between the poverty rates of black retirees with and without public pensions. Less than 3 percent of black retirees with public pensions lived below the poverty line in 2014, which is nearly 87 percent lower than the 21.8 percent of black retirees without public pensions who lived in poverty, as shown in Figure 4. Black retirees were nearly twice as reliant on public pensions to provide a secure retirement as the retiree population as a whole.

Public pensions make an even greater difference in the poverty rates for retired women. Higher shares of retired women of all races live in poverty than do retired men, both for retirees with and without public pensions. Public pensions make the greatest difference in retirees’ chance of being in poverty for black women: nearly a quarter (24 percent) of retired black women without public pensions are in poverty, while just 3 percent of black women with public pensions are. This is a significantly larger difference than for retired black men: 19 percent of retired black men without public pensions are in poverty, compared to 3 percent of retired black men with them.

How Cuts to Public Employment and Pensions Hurt Black Retirees

Given the crucial role of public pensions in African American retirement security, the decline of both public sector employment and the pensions these jobs offer has already hurt the retirement prospects of current black workers; if this decline continues, the impact on black retirement security may be catastrophic. The reduction in public employment has meant fewer stable middle-class jobs for black workers, who have relied on public employment as a pathway to the middle class for more than half a century. The cuts to public pensions mean that even for those black workers fortunate enough to get one of the shrinking pool of public sector jobs, they’re forced to shoulder an increasingly large share of the retirement security burden. And given the poverty rates cited above for black retirees without public pensions, we can predict that the impact of these cuts will be grim indeed.

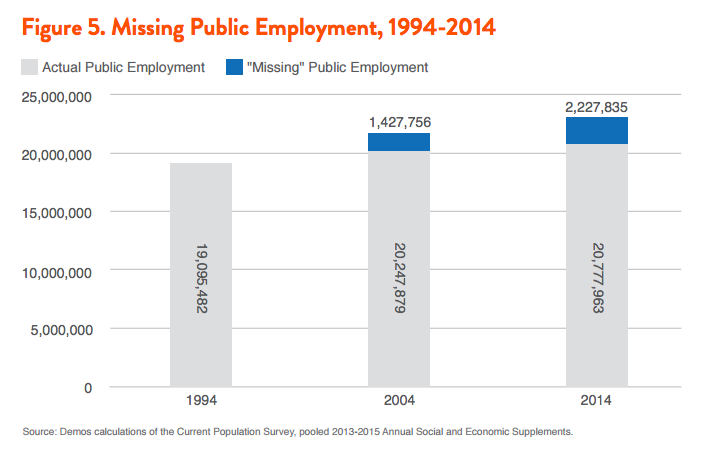

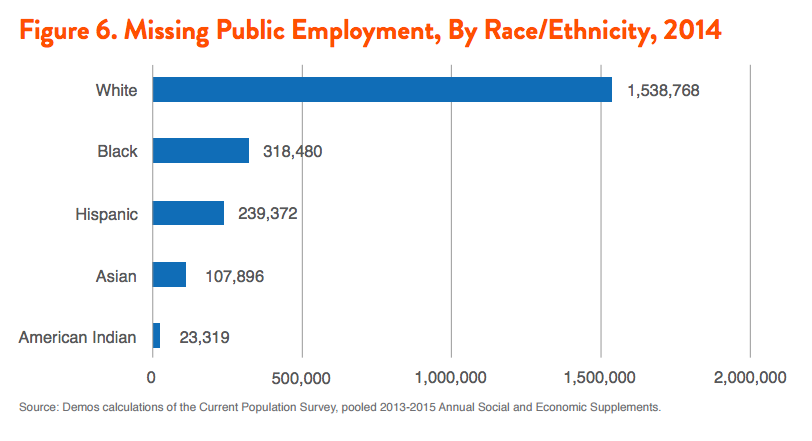

Figure 5 shows total federal, state, and local government employment between 1994 and 2014. Although total public employment has risen slightly—by about 9 percent—over the past two decades, the total U.S. labor force grew much faster over the same period, rising by 21 percent. This means that the share of all workers employed by the government has fallen since 1994, reducing government’s capacity to serve our ever-growing population. If the share of workers in public employment had merely held constant over the past 20 years, there would be nearly 2.3 million more public jobs today; this is the “missing” public employment that Figure 5 depicts. Given that 14.3 percent of public workers in 2014 were black, this translates to almost 320,000 lost public jobs for black workers in the past two decades, a huge blow for the black middle class and their retirement security. Figure 6 breaks down the missing public employment by race/ethnicity based on current composition of the public employee workforce.

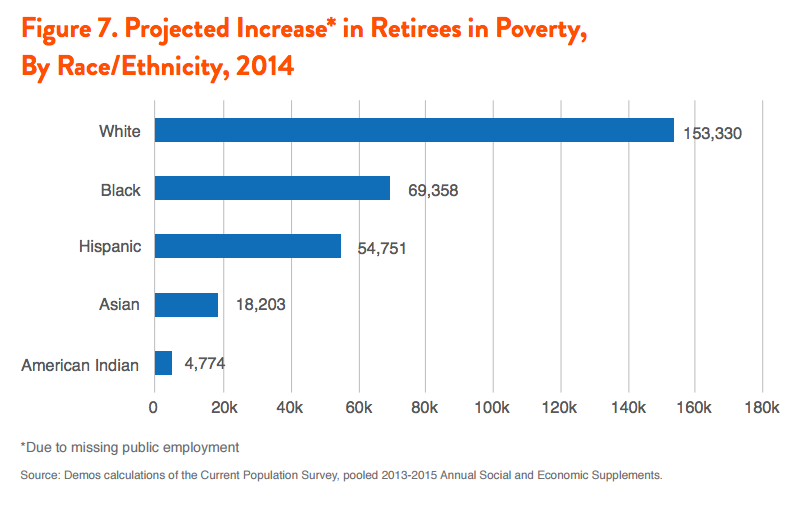

In addition to the decline in economic security during workers’ careers, this missing public employment will impact workers’ future retirement security as well. Figure 7 shows the projected additional number of retirees living in poverty due to lost pensions from missing public employment. We project that more than 275,000 additional workers will suffer impoverished retirements from these cuts, including nearly 70,000 black retirees. In this way, missing public employment is really a double blow to workers, hitting them with decreased economic security and a lower standard of living both during their working lifetimes and after they retire.

The impact of the recent cuts to public pensions is harder to quantify, because we won’t know how the cuts have affected workers’ retirement security until the workers affected by the cuts retire. The majority of African American retirees in 2014 who worked in the public sector began their careers between the 1960s and 1980s, before the recent waves of pension cuts were enacted. However, by examining the breadth and magnitude of recent cuts, we can form a reasonable prediction of their effects on the retirement security of future retirees.

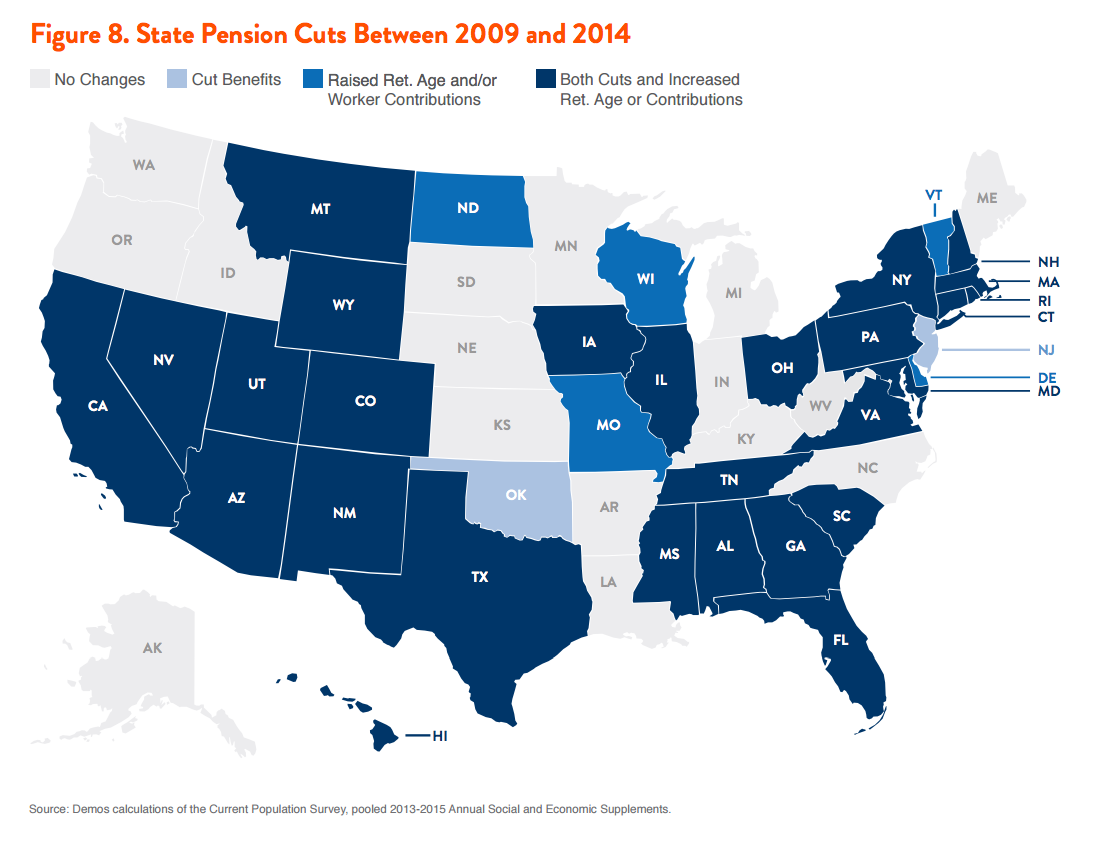

Unfortunately, in the past five years, state pension cuts have been widespread. Figure 8 maps state pension cuts since 2009. Thirty-four states have either cut benefits for new workers, raised their retirement age (which is effectively a benefit cut) or increased workers’ required pension contributions (which, though not a benefit cut, is in essence a salary cut), or enacted multiple reductions, as has happened in the majority of states that have made pension cuts. And these cuts have been far from minor: in the 24 states that made direct cuts to pension benefits—i.e. changed the formula by which benefits are calculated—such cuts averaged 7.5 percent of a future retiree’s projected annual benefit. Nine states cut benefits by 10 percent or more, and four—Alabama, Maryland, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania—cut benefits by at least 19 percent. These cuts mean that public workers in these 24 states will have to save an average of an additional $50,022 each in individual retirement savings to replace the retirement income lost through the cuts enacted in just the past 5 years.

The twin threats of declining public sector employment and cuts to public pensions pose a grave threat to the retirement security of current and future African American workers. The overall poverty rate of black retirees in 2014 was 19.7 percent, 75 percent higher than the overall retiree poverty rate of 11.3 percent. If public jobs continue to disappear and public pensions continue to be cut, future black public workers will be forced to rely on defined contribution plans—401(k)s, IRAs, etc.—to supplement Social Security to provide adequate retirement income. But the documented failure of 401(k)-type plans to provide retirement security for private sector workers make this a dangerous path indeed. The high fees and multitude of risks that 401(k)s force savers to shoulder make these plans entirely unsuitable to be workers’ primary supplement to Social Security for retirement income. Clear evidence of the insufficiency of 401(k)-type plans is apparent in the incomes of retirees without public pensions, illustrated in Figure 3 above. As the figure showed, the median income of retirees without public pensions in 2014 was just $17,184, meaning that more than half of private-sector retirees receive nearly all of their income from Social Security, leaving them far from the dignified retirement once promised to most hard-working Americans.

Why are 401(k)s such inadequate replacements for defined benefit pensions? Workers with 401(k)s find their retirement savings exposed to a number of significant risks and costs, which together make it difficult for workers to save enough for retirement to maintain their standard of living. Defined benefit pensions largely protected workers from these risks and costs, which explains a significant share of the gap in retirement income, depicted in Figure 3 above, between workers with and without public defined benefit pensions. These risks include:

- Investment Risks: As individual accounts, a worker’s 401(k) balance at retirement is dependent in large part on the ability of each worker to choose the right investments for their savings, and the performance of those investments. Forcing savers to make complex investment decisions with long-term consequences naturally leads many to make poor choices: they invest too heavily in low-performing options such as bonds and money market accounts, sell investments when markets drop, or simply contribute too little, all of which can lead to insufficient retirement savings. Defined benefit pensions, whose assets are invested by professional investment managers, protect workers from these risks, leading to better performance.

- Leakage Risk: 401(k)s, unlike defined benefit pensions, allow workers to withdraw from their savings pre-retirement. Because 401(k)s depend on the long-term compounding of investment returns over workers’ entire careers, early withdrawals from retirement savings, particularly early in workers’ careers, can significantly reduce the size of 401(k) nest eggs at retirement. But many workers, particularly low- and middle-income workers with little or no additional savings, are forced to make damaging early withdrawals to pay for unexpected medical expenses, down payments on homes, or educational expenses for themselves or their children. And the impact of these withdrawals on individual retirement savings is considerable: in 2010 alone, early withdrawals totaled $82.4 billion, effectively offsetting nearly a quarter of all contributions to individual accounts that year.

- Longevity Risk: Unlike defined benefit pensions, which provide a steady stream of income throughout retirement, retirees with 401(k)s must attempt to make their savings last the rest of their lives. Annuities available through private markets are often expensive, costing workers a large chunk of their savings. Because of this, retirees with 401(k)s are forced to either self-annuitize by living off only their investment returns or attempt to predict how long they will live, both of which lead to a lower standard of living.

- Disability Risk: 401(k)s are also a bad deal for workers who become disabled during their working lives. Although workers who become permanently disabled can make withdrawals from their 401(k)s without paying the 10 percent penalty typically incurred by early withdrawals, their post-disability standard of living is likely to suffer because of the “back-loaded” nature of 401(k) investment returns: because of the way compound interest functions, workers with 401(k)s earn the vast majority of their investment returns in the years approaching retirement.

- Fee Risk: Participants in any type of retirement plan, whether a 401(k) or traditional pension, pay fees to financial services companies for a variety of services, including administration, recordkeeping, and investment management. However, because of the plans’ individualized nature, 401(k) participants typically pay significantly higher fees than workers with defined benefit plans. And though these fees may seem small, averaging 1-2 percent of savers’ account balances each year, over a lifetime, they can significantly reduce the size of workers’ nest eggs at retirement. In a previous study, Demos showed that an average two-earner household that saves between 5 and 8 percent of its income each year in a 401(k) and pays fees averaging 1.5 percent will have, by retirement, lost nearly $155,000 in fees and lost returns, reducing the size of their nest egg by more than 25 percent.

For a more in-depth explanation of the risks of 401(k)s and the impact of fees on retirement savings, see two prior Demos papers: The Failure of the 401(k) and The Retirement Savings Drain.

What Needs to Be Done

If we wish to prevent the erosion of the retirement security of African American workers, and all workers, we need a significant shift in our country’s retirement policy. And we need to act now, before this erosion becomes too difficult to stop. Moreover, we also need to strengthen retirement security for those workers, particularly private sector workers, who are at risk of poverty or significantly-lowered living standards in retirement. Ensuring retirement security for all workers, particularly those most vulnerable or at-risk, requires substantial policy change, equal to the magnitude of the growing retirement crisis. To truly confront the crisis, we need to reform and strengthen each of the three legs of the apocryphal “three-legged stool” of retirement security: public defined benefit pensions, individual retirement savings, and Social Security.

- Protect public pensions: Defined benefit pensions are the safest and most efficient means of providing supplemental retirement income: they have lower average fees than 401(k)-type plans, ensure a steady and predictable stream of income that is guaranteed to last through retirement, and deliver higher average returns. Unfortunately, defined benefit plans have all but disappeared from the private sector, but many public sector jobs still provide them. Protecting public sector defined benefit plans is necessary to ensure the continued retirement security of public workers. Specifically, we need to:

- Prevent further cuts to defined benefit plans: As Figure 6 showed, a majority of states have cut their public pensions in the past 5 years. These cuts have not only damaged public workers’ retirement security, but are unnecessary: the majority of state pension systems are adequately funded, and funding gaps are largely due to states skipping pension contributions, not overly-generous benefits. States and localities need to refrain from cutting further, and protect benefits for both current and future workers.

- Avoid conversions to “hybrid” pension systems: Five states have converted their pension systems to “hybrid” plans, replacing their defined benefit pensions with a combination of a smaller defined benefit pension and a defined contribution plan. As introduced in the previous section, the risks and fees of defined contribution/401(k)-type plans make them inadequate vehicles for providing retirement security. If we aim to preserve public sector retirement security, we must avoid hybrid plans.

- Reform/Replace the 401(k): Private sector workers, who generally don’t have access to defined benefit plans, need a better retirement savings vehicle than the 401(k)-type plans that are the private-sector norm. The problems with 401(k)s have been well-documented, as their multitude of risks and high fees make it nearly impossible for workers to save enough for retirement. To ensure retirement security for private sector workers, we need to provide a retirement savings plan that protects workers from the risks and fees of 401(k)s; i.e. a plan that has many of the advantages of defined benefit plans:

- Create American Retirement Accounts: Demos has proposed creating new retirement savings accounts called “American Retirement Accounts,” which would provide many of the advantages offered by defined benefit plans. The accounts would be available to all workers, completely portable between jobs, provide a guaranteed minimum inflation-protected return, and allow workers to annuitize their balances at retirement. We also propose converting the existing tax deduction for 401(k) savings to a flat contribution from the federal government into each worker’s American Retirement Account, benefitting lower-income workers who currently receive little to no benefit from the deduction.

- Protect and expand Social Security: Since its inception, Social Security has been, and continues to be, the primary source of retirement income for lower-income workers, and is particularly important for workers of color, who are less likely to have access to a workplace pension. To ensure that Social Security continues to provide a basic standard of living for lower-income retirees, we need to:

- Ensure the long-term solvency of the Social Security Trust Fund: The Social Security Trust Fund is currently projected to be exhausted in 2034, after which payroll taxes are projected to be able cover just 79 percent of promised benefits. There are many ways that the funding gap could be closed, but most, including the “default” option of across-the-board benefit cuts or a universal payroll tax increase, would be particularly detrimental to the retirement security of workers of color and low-income workers. The best policy option for closing the funding gap is to eliminate the cap on earnings subject to the Social Security payroll tax, currently set at $118,500. Eliminating the earnings cap would close approximately 86 percent of the program’s funding gap, and is the fairest way to ensure the program’s solvency for generations to come.

- Raise benefits for low-income workers: As of October 2015, the average annual Social Security benefit for retired workers was $15,511. Of the half of retirees who receive the average benefit or less, many have little to no additional retirement income; thus, low Social Security benefit levels consign them to a retirement in poverty, or just above it. We need to increase Social Security benefits for low-income workers so that the program can provide an adequate retirement income floor.

By protecting existing public pensions, creating new retirement savings accounts for private sector workers that provide many of the benefits of defined benefit plans, and protecting and strengthening Social Security, we can ensure that workers today and in the future—particularly workers of color—have the chance to retire with dignity, a key part of the American dream.