Introduction

A cornerstone of engagement in the democratic process is exercising one’s right to vote. Advocates who work with individuals struggling to make ends meet know the importance of lifting up in the democratic process the voices of communities affected by poverty, hunger, lack of resources for health care or housing, and racial discrimination. But all too often, a range of practices, including the lingering effects of Jim Crow laws and more recent efforts to restrict voting among eligible people, create obstacles that strip people of color, the hungry, and the poor of the fundamental right to vote.

More than 85 percent of citizens with family income at or above $150,000 reported being registered to vote in November 2016, compared to only 57.7 percent of those with incomes below $10,000. Rates of reported registration in November 2016 also varied by race and ethnicity: 71.7 percent among white people; 69.4 percent among black people; 56.3 percent among Asian people; and 57.3 among Hispanic people (of any race). If low-income citizens were registered at the rate of citizens with higher incomes, millions more Americans would be registered to vote, contributing to a healthier democracy that more fully reflects the nation.

Tens of millions of voting-age citizens interact with state public assistance agencies across the nation—applying for benefits, recertifying for benefits, or submitting a change of address—making these agencies a key venue to reach eligible people with voter registration opportunities.

Section 7 of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) of 1993—which applies to public assistance agencies—provides anti-hunger, anti-poverty, and health care access advocates with an often untapped opportunity to help close the voter registration gap. There are key steps advocates can take to help state public assistance agencies comply with the NVRA and ensure additional eligible people have the opportunity to register and exercise their right to vote.

The National Voter Registration Act

Congress passed the NVRA to increase the number of citizens registered to vote and to help address past discriminatory practices in voter registration. The best-known part of the NVRA requires states to offer voter registration opportunities when people apply for driver’s licenses, and it is often referred to as the “Motor Voter Act.”

The NVRA also includes an equally important provision which applies to agencies that administer several public assistance programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and state programs serving people with disabilities. Congress included health and public assistance programs in the NVRA to reach the varied populations—including persons of color, young adult and elderly citizens, lower-income households, highly mobile populations, and people with disabilities—who are less likely to drive or otherwise interact with the DMV, but who could be reached through these other government agencies.

Under Section 7 of the NVRA, state public assistance agencies are required to affirmatively provide clients with the opportunity to register to vote any time they apply for benefits, recertify their benefits, or submit a change of address. Among other duties, agency staff must:

- Provide a voter registration application to each person applying for benefits, requesting renewal of benefits, or making an address update, unless an individual affirmatively declines, in writing, the opportunity to register to vote.

- Ask the applicant, in writing, whether they would like to register to vote or update their voter registration address.

- Inform the applicant, in writing, that no one may interfere with their right to register to vote or not register to vote, the right to privacy while registering, and the right to choose a political party.

- Provide assistance to applicants in completing the voter registration application form, to the same degree as assistance is provided in completing the benefits application.

- Transmit completed voter registration application forms to the appropriate election official within strict time limits after the client completes the application.

Since its implementation in 1995, Section 7 of the NVRA has succeeded in facilitating the registration of millions of low-income voters and supporting a more diverse electorate. Based on data collected by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, 1.7 million individuals registered to vote at public assistance agencies in 2016, 1.6 million did so in 2014, and 1.8 million did so in 2012. Through an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data, Demos found that registration through public assistance agencies increases the diversity of registrants by adding more low-income people and people of color to the voting rolls.”

Despite the law’s success in diversifying the electorate, over the years many states have failed to provide voter registration opportunities in a way that fully complies with their obligations under Section 7 of the NVRA. As a result, millions of eligible potential voters who have interacted with state public assistance agencies across the nation have been denied the opportunity to register to vote, a precursor to voting and making their voices heard.

At times, lack of compliance is due to blatant disregard of the law, which may be fueled by an agency’s hostility to providing voter registration to the people they serve. Often, however, disregard of the NVRA stems from it being overlooked or deprioritized because of leadership’s failure to reinforce the importance of voter registration as a federally required obligation, a lack of consistent training of staff on their voter registration responsibilities, or both. Agencies may be struggling with implementing new systems or overwhelmed by caseloads such that they overlook their voter registration responsibilities, and their leadership may not make clear enough that providing voter registration is a requirement of federal law and a priority for the agency.

This points to the tremendous untapped potential of the NVRA, and the urgent need to do more to connect millions of people to the right to vote. Better implementation of Section 7 of the NVRA would create a more diverse and representative electorate and, in turn, strengthen our democracy.

Improving NVRA Compliance at State Public Assistance Agencies Can Make a Difference

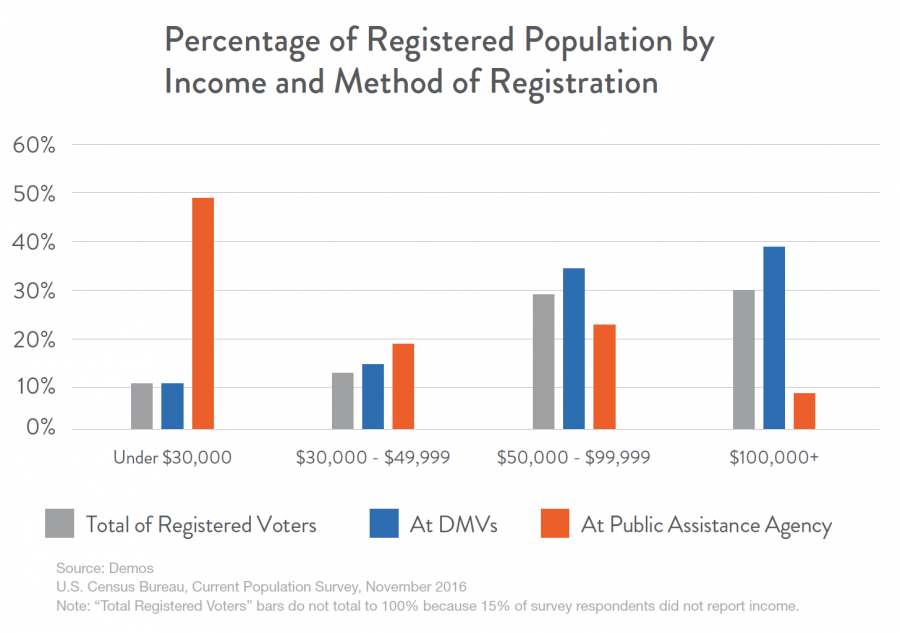

With more focus on harnessing the potential of the NVRA at state public assistance agencies, advocates can ensure more of the millions of eligible, unregistered low-income people and people of color have the necessary access to vote. A look at the promise of Section 7 of the NVRA in closing the voter registration gaps for low-income people and people of color is represented in these charts from Demos:

The lowest income registrants—those making less than $30,000 per year—register at public assistance agencies at disproportionately high rates. In 2016, registrants making less than $30,000 per year were only 11 percent of the total registered population, while they represented nearly half—49 percent—of those who reported registering to vote at public assistance agencies.

Some communities of color register at public assistance agencies at much higher rates than their presence in the general registered public. In 2016, black registrants made up 13 percent of the total registered population, but they represented 35 percent of those who registered to vote at public assistance agencies. Latinos made up 10 percent of all registered people but 19 percent of those registered at public assistance agencies.

If a state adopts automatic voter registration at its Department of Motor Vehicles, does that eliminate the need for voter registration through public assistance agencies?

No, it does not. A growing number of states are implementing automatic voter registration (AVR) for individuals applying for or renewing a driver’s license, with very promising results. AVR is a voting system modernization that allows states to efficiently and cost-effectively register eligible individuals to vote. Through data matching and the pre-population of forms, AVR enables states to use information an eligible person provides during an interaction with a state agency, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), for voter registration. This results in more individuals being registered, and time and cost savings for states. Despite the successes of AVR in helping register millions of voters, in most states AVR is only available for people who interact with the DMV.

Low-income people may be less likely to benefit from AVR because they are less likely to have a driver’s license than high-income people or may be less able to renew their driver’s license if they have fees or parking fines they are unable to pay. Low-income people also may face challenges if DMV locations are far from their homes and transportation options are limited. People may not be able to incur the costs of missed wages or bus fare.

Congress was explicit about the inclusion of public assistance agencies and the reason for doing so when designing the NVRA: “If a State does not include [such agencies] … it will exclude a segment of its population from those for whom registration will be convenient and readily available—the poor and persons with disabilities who do not have driver’s licenses and will not come into contact with the other principal place to register under this Act.”

If a state has online voter registration, does that eliminate the need for voter registration through public assistance agencies?

No, it does not. Online voter registration is available in almost 40 states, making it more convenient for people to register, and resulting in cost savings for states. However, this promising modernization does not reach everyone. Low-income people may not be able to use their state’s online voter registration system because most systems require that the prospective user have a driver’s license or a state-issued identification. Or, they may not have access to a computer or broadband to use the system. Some states are working to expand access to these systems, but improvements like this take time and will not negate the need to provide voter registration opportunities at public assistance agencies.

Voter registration system modernizations are helping millions of eligible people more readily register to vote. These modernizations, however, sometimes have features that unintentionally exclude some eligible people, particularly members of the electorate who have historically been most disenfranchised, such as low-income people and people of color. The NVRA continues to play a fundamental role in ensuring access to voter registration among low-income people and people of color, and it is critical to continue ensuring its effective implementation alongside other voter registration modernizations.

Advocates Can Take Steps to Help Low-Income People Register to Vote

Engaging in work to improve agency NVRA practices is a permissible activity for 501(c)(3) organizations. Nonprofit groups can get involved in advocating for better NVRA compliance, because it is a nonpartisan way of encouraging registration. The NVRA prohibits states from influencing a person’s decision about registering to vote, promoting a political party, telling people how to vote, or requiring people to register to vote.

Anti-hunger, anti-poverty, and health care access advocates are well-positioned to play an important role in ensuring NVRA implementation because of their strong relationships with many of the state agencies that administer SNAP, Medicaid, and TANF and their expertise in how state public assistance agencies operate. Advocates also have strong connections to the clients served by these agencies and are more likely to understand the importance of engaging low-income people and people of color in the democratic process.

Below are 5 ways advocates can support opportunities to register people to vote through public assistance agencies:

1. Reflect on the importance of political participation by low-income communities to your organization’s mission.

Advocating to help low-income people and people of color exercise their right to vote is essential to work to end hunger and poverty, and to address racial inequality. Due to disparate rates of voter registration, many of the clients your organization serves are likely missing out on the opportunity to participate in the democratic process fully and to voice their support for actions that address their needs. Candidates and elected officials take notice when people in a community vote and do not vote; they are less likely to focus on issues—such as hunger and poverty—and solutions—such as federal programs—that are critically important to non-voters.

2. Be at the table.

You don’t have to be an expert on the NVRA; just reach out to those who are. By bringing new voices to efforts to ensure NVRA compliance at public assistance agencies, you can support the expertise and efforts of nonpartisan voting rights groups working in the anti-hunger and anti-poverty space. Get to know the groups in your state so you can draw on their knowledge and share the expertise you have to offer. Many national groups, like Demos, League of Women Voters, Nonprofit VOTE, Rock the Vote, and State Voices, have state affiliates or partners. Get to know them to stay informed of opportunities to share expertise with other advocates that can make a difference.

3. Become a Section 7 NVRA champion.

If you are already working with staff at public assistance agencies, it doesn’t take much time to be an NVRA champion. Simply asking a question about what the state agency or local office is doing around Section 7 of the NVRA can unleash a flurry of behind-the-scenes questions about whether training for agency staff has been offered recently, whether voter registration is being offered with each transaction (in-person, online, by telephone, by mail), whether voter registration applications completed by clients have been submitted to election officials in a timely way, or whether there is an NVRA coordinator at the agency (an agency staff member who should be familiar with the requirements of the NVRA, responsible for coordinating and overseeing compliance with the NVRA within the agency, and ensuring regular NVRA education and training programs are provided for agency staff).

Posing the following questions during your meetings with agency staff can be helpful in reminding busy agency staff about the need to comply with this critical voting rights law:

- When was the last time you trained staff on their voter registration responsibilities under the NVRA?

- When do you plan to hold the next training?

- Do you have voter registration applications on hand in your offices?

- When someone applies for benefits online or by telephone, how are they connected to voter registration opportunities?

- Have you thought about improving voter registration opportunities during the next upgrade, and when will the upgrade occur?

- What happens when someone checks the box that they want register to vote on the online or paper application?

- How does your office ensure that voter registration applications are submitted to election authorities in a timely way?

- When people apply for public benefits renewal, are they provided voter registration opportunities and assistance completing the application?

- When people are submitting change of address information, are they offered voter registration opportunities and assistance completing the application?

- Is compliance with voter registration responsibilities included in your staff review or performance appraisal process?

- Who is your NVRA coordinator and do you have their current contact information?

4. Make your asks timely.

A key asset you have that voting rights groups often don’t is in-depth expertise on how state public assistance agencies function. You can help identify points in time that are prime to improve NVRA compliance, and share this information with voting rights partners. For instance, if you know that the online system to apply for benefits is being upgraded, remember to ask how the agency plans to incorporate voter registration requirements. If the state is revising its recertification packet or adding staff to a call center, ask how the plans include complying with Section 7 of the NVRA. Likewise, let voting rights groups know about your concerns about balancing demands on the agency. For instance, let them know if you believe that pushing for better NVRA compliance when the agency is failing to process SNAP or Medicaid applications in a timely manner raises delicate questions about pursuing both goals.

5. Help foster a positive voter registration climate at public assistance agencies.

Busy state public assistance agency staff are more likely to comply with the NVRA and connect people to voter registration opportunities if there is institutional buy-in. Staff need support, materials, and training to seamlessly include voter registration activities in their existing work flow; they need to know that their work on voter registration is valued by supervisors. Advocates also need to applaud state agencies for doing good work on this issue and be valuable partners in this effort.

Conclusion

The NVRA is one of the most important and effective ways to ensure better participation and representation of low-income people in the political process. Encouraging and increasing implementation of voter registration requirements at public assistance agencies can expand the numbers of people who register to vote through these agencies. Anti-hunger, anti-poverty, and health care access advocates bring new voices and energy that can help harness the untapped potential of Section 7 of the NVRA and ensure that more low-income citizens have their voting rights protected. By engaging in NVRA advocacy, advocates can make voting more accessible to disenfranchised people, help build stronger communities, and make sure that all Americans have a voice in the political process, including efforts to end poverty, hunger, and racial discrimination.