Introduction

Democracies are healthiest when all people actively participate. Core to that participation—and among the most fundamental rights in our democracy—is the right to vote. However, ensuring that every eligible person has the right to vote, regardless of skin color, language spoken, or income, remains an elusive goal in our democracy. Barriers to voting are plentiful, especially today, amidst the most severe assault on voting rights since the Jim Crow era.

One of the highest hurdles is registration itself. The confusing, sometimes onerous process of registering to vote keeps more people from voting than almost any other barrier. Nearly 1 in 5 (18%) people who were eligible but did not vote in the November 2016 general election cited registration issues as their main reason for not voting. Registering—and keeping a registration up to date—can be especially burdensome for people of color, low-income Americans, and young people, who tend to move more frequently. Additional barriers erected by politicians make it even harder for eligible voters with limited mobility or means, like those who experience long-term illness or disability and those who have limited English proficiency. Taken together, the challenges of getting or staying registered account for a full quarter of eligible people who reported not voting in November 2016.

Automatic voter registration, same-day registration, pre-registration for 16- and 17-year-olds, and other policies that voting rights advocates are pursuing across the country hold great potential to help close the registration gap. Just as important as passing new laws, however, are efforts to preserve and advance existing laws that have already facilitated registration and access to the vote for tens of millions of Americans. Since its passage 25 years ago, few laws have done more to advance voter registration and facilitate voting than the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA).

Each election cycle, millions of U.S. citizens find elections more accessible thanks to the NVRA. The NVRA requires 44 states and the District of Columbia to actively offer voter registration through government agencies like motor vehicle bureaus and departments of health and human services; bans certain onerous state voter-registration policies; and mandates the development and acceptance of mail-in voter registration applications. The NVRA also increases the ability of citizens to remain registered and to update their voter registration records. When implemented properly, the NVRA benefits millions of voters each election cycle.

In enacting the NVRA, Congress presumed that registration through motor vehicle agencies would reach the largest number of people. However, recognizing that such “motor voter” registration would not reach everyone—and to reach as many eligible citizens as possible—Congress also included voter registration through agencies providing public assistance or serving persons with disabilities in Section 7 of the Act. A key, and sometimes underestimated, component of the NVRA, Section 7 requires states to offer clients the opportunity to register to vote through agencies serving households with low incomes and people with disabilities when they apply or recertify for benefits and when they change their address. Thanks to Section 7, millions of new, mostly low-income voters who may otherwise have a hard time registering can be added to the rolls and given the chance to make their voices heard.

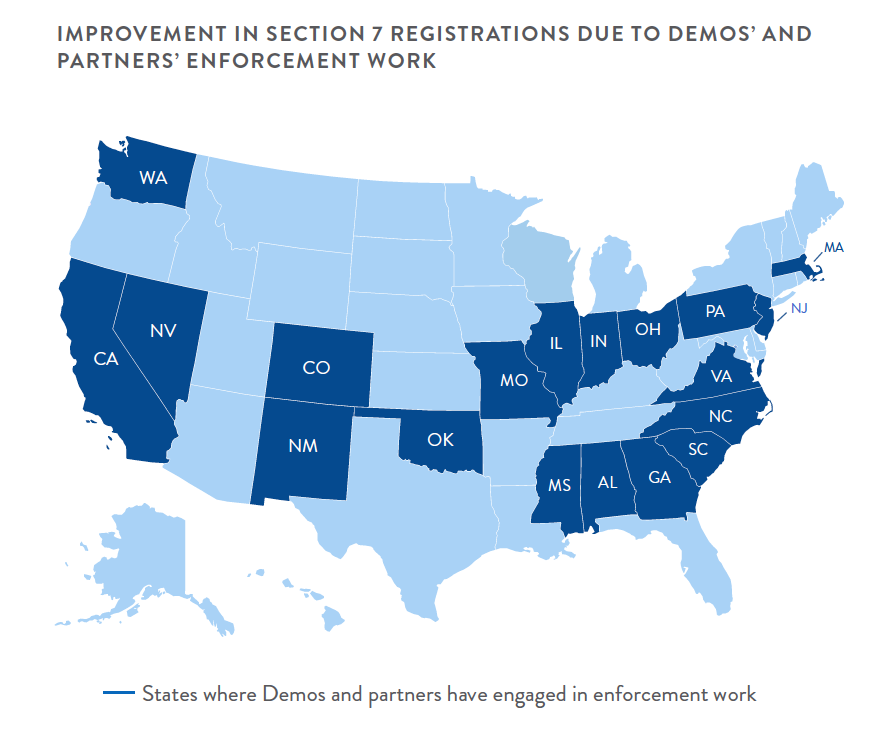

The NVRA has undeniably moved us closer to realizing the promise of democracy. However, achieving its full potential remains an unfinished project. Many states do not comply with various aspects of the law, especially Section 7, resulting at best in missed opportunities to bring millions more people into the political process and at worst the active suppression of certain communities’ voices. Over the last several years, Demos and partners such as Project Vote, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and others have worked to assess and improve compliance with the NVRA through collaboration with election administrators and state-based partners, advocacy, and, when necessary, litigation.

By focusing on compliance at public assistance offices, advocates have sought to diminish the persistent gap in registration rates between low-income communities and wealthier populations. These strategies have made a real impact: We estimate that this compliance work across nearly 2 dozen states has resulted in over 3 million new voter registration applications through public assistance agencies covered by Section 7 of the NVRA.

In recognition of 25 years since the NVRA's passage, this report reviews some of the achievements, challenges, and unmet potential of Section 7 of this landmark voting rights law. Key findings include:

- The National Voter Registration Act boosted the voter registration rate nationally to 73 percent and resulted in 27.5 million new voter registration applications during the first election cycle after its enactment.

- Communities that have historically faced higher barriers to registering and voting—including low-income communities and some communities of color—benefit from the NVRA, especially through registration at public assistance agencies under Section 7 of the law.

- The NVRA’s full potential is left untapped by states that do not consistently comply with their obligations under the law, but enforcement work by Demos and partners leads to significant improvement in registration rates at Section 7 agencies.

- States can do more to improve their compliance with the NVRA, to make voter registration more accessible to all eligible residents, and to reduce the registration gap between communities—from incorporating automatic voter registration and improving technology in agency transactions, to enhancing training and oversight of voter registration responsibilities and expanding the types of agencies that provide voter registration.

Need: Ongoing Barriers to Voter Registration

For much of our nation’s history, states and the federal government have limited or prevented the right of non-wealthy, non-white people and women to vote. Whether through violence and explicit prohibitions that restricted the franchise to white, land-owning men, or via de facto exclusion through poll taxes, literacy tests, and other suppression devices, for nearly 2 centuries, millions of Americans—especially African Americans and other communities of color—were denied the opportunity to cast a ballot and make their voices heard. Even after the 15th amendment guaranteed men the right to vote, states, especially in the South, that sought to deny the franchise to black and brown Americans used the registration process itself as a voter suppression tactic.

Alabama, for example, passed a new constitution in 1901 with the express purpose, as convention president John B. Knox reminded attendees in his opening address, of “establish[ing] white supremacy in this State.” The constitution laid out new requirements for anyone wishing to register to vote, including poll taxes, literacy tests, and employment and property qualifications, which together prevented virtually all black Alabamans from registering, along with many poor whites. Further cementing the purpose of the provisions, the constitutional framers included a temporary provision, a “grandfather clause,” that allowed anyone descended from a confederate soldier—which covered poor whites but excluded blacks, who were not allowed to serve in the military—to register and to carry their registration with them for life.

Discriminatory voter registration procedures continued to evolve throughout the Jim Crow era. In another example, Georgia’s Registration Act of 1958 created new barriers for would-be voters who could not read or write, requiring that before they could register to vote, they answer questions about how a writ of habeas corpus may be suspended, the process to amend the U.S. Constitution, and the qualifications of a representative to the state General Assembly. Such onerous and arbitrary registration requirements were common across the South and were applied unequally to keep certain people—especially African Americans—from accessing the franchise.

Congress passed, and President Lyndon Johnson signed, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) to prevent these and other discriminatory policies and practices. The VRA made significant strides toward ending discriminatory exclusion and making voting more accessible to those who had for centuries been kept from the polls. In addition to other reforms, the VRA eliminated many unnecessary restrictions on voter registration, which were among the factors driving the registration divide in the South and across the country. However, while the VRA eliminated the most egregious and racially discriminatory obstacles to registration like poll taxes and literacy tests, it left in place what the U.S. House of Representatives in 1993 called “a complicated maze of local laws and procedures, in some cases as restrictive as the outlawed practices, through which eligible citizens had to navigate in order to exercise the right to vote.”

States erected arbitrary restrictions on who could conduct registration drives, limited where registration could be offered, and underfunded voter registration sites and materials. In Michigan, for example, those hoping to register voters had to be separately deputized and trained in each county, and local election officials were authorized to refuse to deputize people without explanation. Across several states, registration volunteers were regularly barred from waiting rooms at unemployment and welfare offices, and one volunteer in 1984 was arrested and strip-searched for attempting to register voters at a welfare office in Cincinnati.

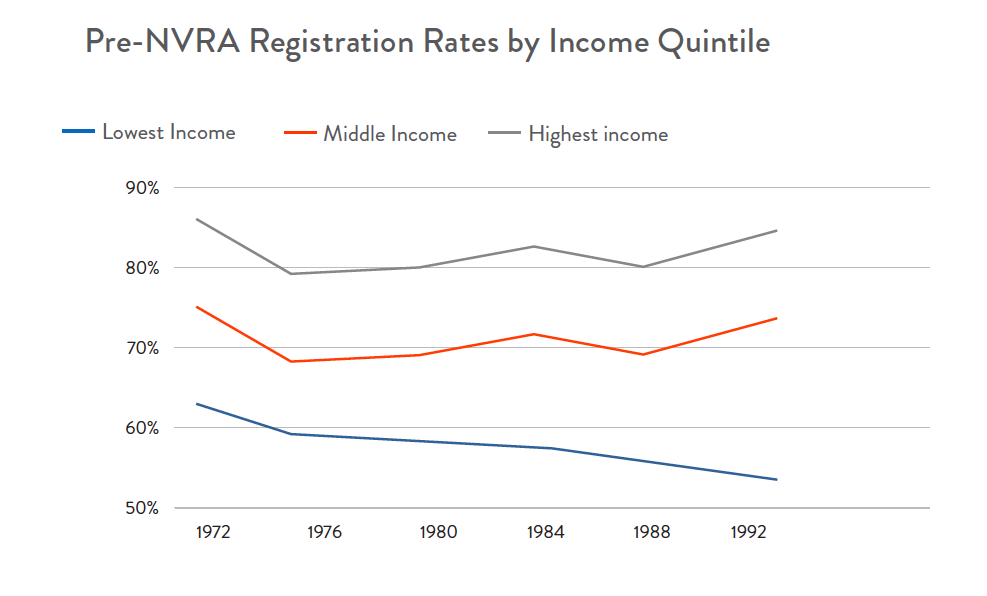

As a result, even with the VRA, disparities in registration rates between communities, particularly based on income, endured. In 1972, the first presidential election after the first reauthorization of the VRA and the passage of the 26th Amendment granting 18-year-olds the right to vote, people in the lowest-income quintile were registered at rates 20 percentage points lower than those in the highest-income quintile; by 1992, the gap had widened to more than 30 percentage points.

By the early 1990s, it was clear that federal legislation was necessary to effectively regulate the voter registration process and ensure registration was available to all eligible Americans, regardless of race, income, or other characteristics. For advocates working to pass such legislation, in addition to simply registering more eligible people, an explicit goal was to reduce inequalities in the registration rate—a policy goal central to making democracy more representative. Congress agreed, designing the NVRA in part to address its finding that:

[D]iscriminatory and unfair registration laws and procedures can have a direct and damaging effect on voter participation in elections for Federal office, and disproportionately harm voter participation by various groups, including racial minorities.

In explaining the reason for including public assistance agencies and agencies serving persons with disabilities specifically, Congress also noted that:

If a State does not include [such agencies] … it will exclude a segment of its population from those for whom registration will be convenient and readily available—the poor and persons with disabilities who do not have driver's licenses and will not come into contact with the other principal place to register under this Act.

Congress introduced and passed the National Voter Registration Act in early 1993, and on May 20, 1993, President Bill Clinton signed the NVRA into law. The reform’s impact was as immediate as it was significant.

Impact: Progress and Potential of Section 7 of the NVRA

Voter registration nationally rose as a result of the NVRA. The Federal Election Commission, the agency initially tasked with monitoring progress of the NVRA, estimated that voter registration grew to 73 percent of the voting age population in 1996, the year after implementation, marking the highest voter registration rate since reliable data became available in 1960. During the 1995-1996 election cycle, 27.5 million new registrants were added to voter rolls across the 44 states (and the District of Columbia) covered by the NVRA, thanks to the new law.

While improvements in registration rates overall are impressive, the success of the NVRA should be especially noteworthy to those interested in closing the registration gap for low-income people, people of color, and other historically disenfranchised populations. The NVRA—particularly Section 7—plays an important role in achieving this principal goal of decreasing voting inequality.

Section 7 of the NVRA requires people be offered the opportunity to register to vote, or to update their registration due to a change of address, when they apply for or receive public services or assistance at state agencies providing public assistance, offices providing services to people with disabilities, armed forces recruitment offices, and any other offices or agencies designated by the state.

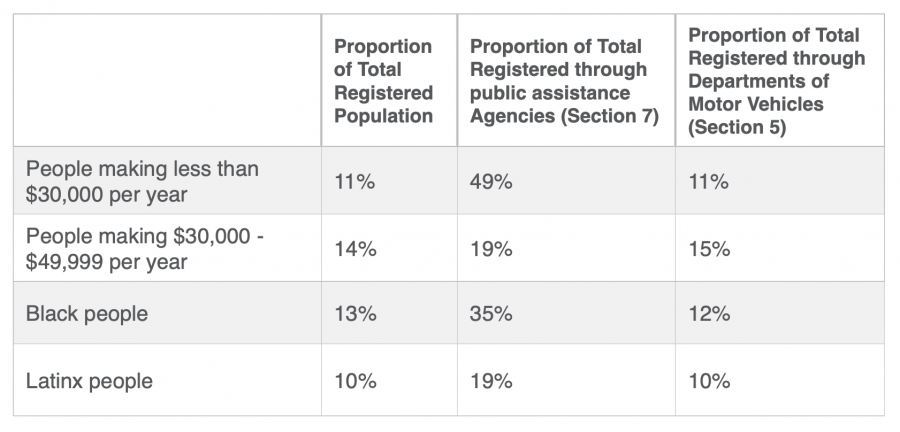

While voter registration at public assistance agencies accounts for a relatively small share of overall registrants, Section 7 is an important mechanism for registering individuals who may otherwise be left out of the democratic process. The table below compares the demographics of people who registered at public assistance agencies (Section 7), those who registered at departments of motor vehicles (Section 5), and all registered people. These comparisons indicate that registration through public assistance agencies increases the diversity of registrants by adding more low-income people and people of color to the voting rolls.

The lowest-income people—those making less than $30,000 per year—are disproportionately represented among those registered through public assistance agencies. In 2016, registrants making less than $30,000 per year were only 11 percent of the total registered population, while they represented nearly half (49 percent) of those who registered to vote through public assistance agencies. Registrants making between $30,000 and $49,999 also registered using Section 7 at disproportionate rates.

Similarly, people registering at public assistance agencies are significantly more likely to be from communities of color. In 2016, black registrants made up 13 percent of the total registered population, but represented 35 percent of those who registered to vote through public assistance agencies. Latinx registrants made up 10 percent of all registered people but 19 percent of those registered through public assistance agencies.

While the NVRA is best known for its Section 5 registration—it is often called the “Motor Voter Law”—these data suggest that Section 7 is performing its intended role to reach people left out of ”motor voter” registration and, as a result, is playing an even more important role in addressing the persistent registration gap facing historically disenfranchised communities.

Despite its impact to date, the NVRA could be doing more. Inequality in registration rates persists across communities, particularly across income groups—a challenge the NVRA was explicitly designed to address. This unfulfilled potential is partially a result of varying compliance on the part of states. Since 1995, tens of millions of eligible voters have been added to the rolls thanks to the NVRA, but millions more eligible voters have been left unregistered, as states have failed to fully meet their responsibilities under the law.

Since the early years of implementation, states have demonstrated differing levels of compliance with their obligations under each section, and particularly under Section 7. Two years into implementation, only 21 covered states had designated more than one state agency to participate in voter registration, as required under Section 7, and 4 states had not designated any agencies to participate at all. Even after many of these early deficiencies were overcome, audits and investigations by Demos and other voting rights advocates in the years since have revealed additional problems—including failure to offer voter registration during agency interactions, to provide support completing those applications, or to transmit completed applications to election officials in a timely way.

To address this non-compliance and move the country closer to full registration, in 2005 Demos and its organizational partners began to conduct NVRA enforcement work across the United States. This ongoing work includes assessment of states’ compliance through data analysis, public records review, field investigations, and engagement with community partners; collaboration with state officials when possible, advocacy when appropriate, and litigation when necessary; and post-intervention technical support and settlement monitoring. After Demos’ and partners’ enforcement work began in 2005, the number of overall voter registration applications received from public assistance agencies increased dramatically—and they have continued to increase almost every year.

Between 2007 and 2016, the federal Elections Assistance Commission (EAC) reported 7.5 million new voter registration applications from public assistance agencies across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. As the map and chart below show, Demos’ and partners’ work is directly responsible for more than 3 million new voter registration applications through public assistance agencies in 21 states across every region of the country.

a. California’s intervention impact number reflects the number of voters registered through the state’s health benefit exchange since 2014. California was the first state to designate its state-run health benefit exchange a voter registration site, after advocacy by Demos and partners. There are no pre-intervention data because the state-run ACA exchange was not in operation prior to 2014.

b. The Department of Justice intervened in Illinois after Demos alerted the Department to the enforcement issue and advocated for its intervention. Actual registrations post-reform calculated using EAC data.

c. Massachusetts’ intervention impact number includes both improvements in monthly registrations and the 31,453 applications generated by a one-time remedial voter registration mailing that the state sent in the summer of 2012.

d. Actual registrations post-reform calculated using EAC data.

e. Actual registrations post-reform calculated using EAC data.

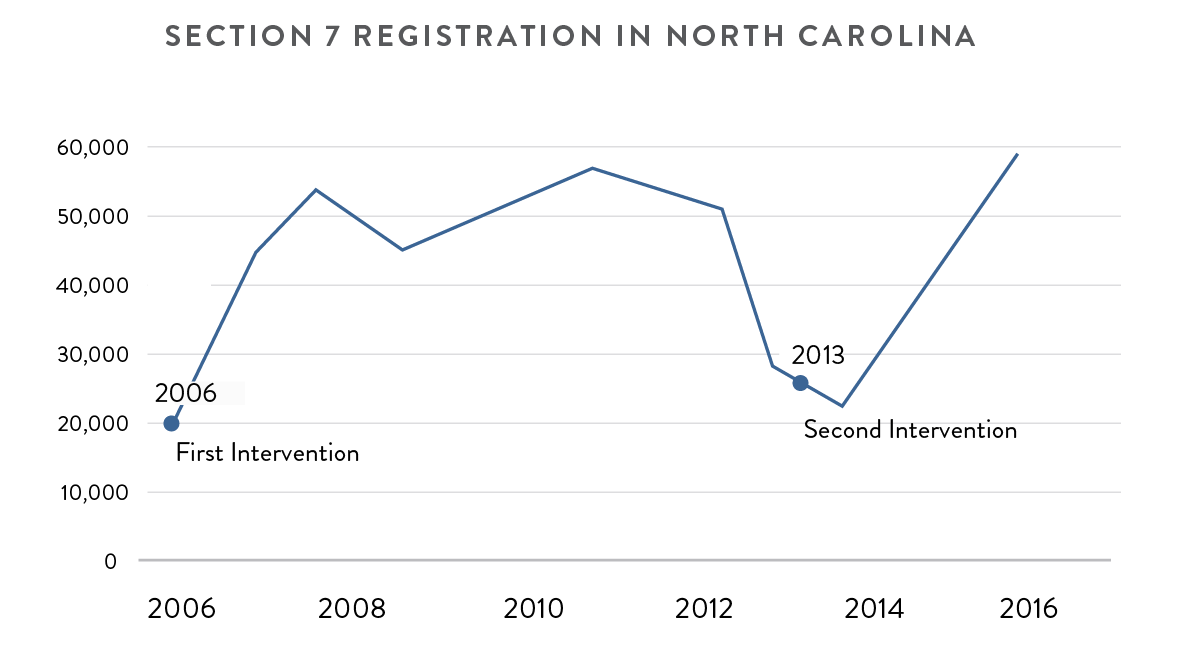

f. North Carolina had two interventions. The first involved technical assistance and several years of improved compliance. The second, after a change in the state’s political leadership and subsequent poor compliance, involved lengthy litigation that ultimately led to a settlement agreement.

A state’s projected registration totals without reform are calculated using voter registration applications at public assistance agencies, as reported to the Election Assistance Commission, and initial applications for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits during the pre-intervention period. With 3 exceptions, actual registration totals with reform come from administrative data provided by states under settlement agreements or cooperative arrangements, which advocates use to monitor progress during the intervention period. In Illinois, Missouri, and Montana, limitations of state administrative data require us to use EAC data for our post-reform calculation as well. The intervention impact number represents the difference between the registrations projected without reform and the actual registrations post-reform: more than 3 million voter registration applications that likely would not have been submitted without Demos’ and partners’ enforcement efforts.

These impact estimates are conservative and likely an underestimate of the actual impact of Section 7 enforcement work. Since many states stop providing administrative data after the settlement Demos and partners achieved expires, these estimates do not account for the continued heightened registration at public assistance agencies after an official settlement period ends. Judging by publicly available EAC data, in many cases states continue to register people at public assistance agencies at higher rates than they did before our engagement. Additionally, some states include voter registration applications in mailed recertification applications, and such registrations returned to the Secretary of State may not be captured as public assistance agency-initiated registrations.

Despite lingering issues in some places, improvements in compliance brought about by advocacy and litigation have resulted in significant increases in voter registrations through Section 7 agencies. In some states, these increases have been particularly dramatic. Mississippi saw an 1800 percent increase in the number of Section 7 voter registration applications generated during the intervention period, with nearly 222,000 additional Mississippians completing voter registration applications. Pennsylvania experienced a 1600 percent increase, leading to 319,000 additional residents applying to register to vote. And Georgia achieved a 1000 percent increase, meaning 250,000 additional Georgians were able to submit voter registration applications during the intervention period.

The nature of Demos’ and partners’ enforcement work varies by state, as does its impact. The following examples highlight distinct enforcement avenues, ranging from cooperative work with agency officials and election administrators to litigation and formal settlement agreements.

Alabama: Negotiation and Cooperation

In early 2012, public records review and a field investigation revealed widespread Section 7 non-compliance at Alabama’s Department of Human Resources (DHR) and Medicaid offices. Negotiating on behalf of the Alabama chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Demos, Project Vote, and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law secured a voluntary settlement agreement with the Secretary of State, DHR and Medicaid in 2013 to improve compliance and avoid litigation.

Prior to our intervention, Section 7 agencies in Alabama were registering just 4 percent of clients who came through their doors, an average of 874 voter registrations per month. After working with Demos and other advocates to improve compliance, Alabama Section 7 agencies began offering voter registration consistently and improved their registration rate to 14 percent of eligible clients, or an average of 3,649 voter registration applications per month.

Regina Cowarts is an Alabaman and a Medicaid and DHR client who had not received the opportunity to register to vote through either agency. Improved compliance due to our intervention and the settlement meant that Regina successfully registered before the 2012 general election, and her sons also became voters. Regina describes the profound impact more accessible registration had on her family:

“Both of my sons are registered voters now after receiving the voter registration form from the food stamp office in my reapplication envelope. Now our house is a 3-voting household thanks to this program. It only took a few moments to fill out the application and within a month they had their voter cards. They were both able to vote in our last election and will be able to vote in the upcoming election. It was a proud day for me to walk in with my oldest son to vote in the presidential election. And he was pretty pumped up about it, too.”

North Carolina: Initial Cooperation, then Political Change and Litigation

Demos and its partners prefer to collaborate with states on NVRA compliance before pursuing any litigation. However, these collaborations can be fragile, especially as state politics and personnel change. Demos first engaged with North Carolina in 2006, after discovering the state was severely out of compliance with the NVRA. Surveys conducted outside public assistance offices in 2 of North Carolina’s major cities, Raleigh and Greensboro, yielded not a single person who was offered voter registration services in interactions with the agency. Data submitted by North Carolina to the Federal Election Commission and Election Assistance Commission indicated a 73.5 percent decline in public-assistance voter registrations in the state between initial implementation of the law in 1995-1996 and the 2003-2004 reporting period. After Demos and Project Vote notified the state of its non-compliance, North Carolina swiftly sought technical support to improve voter registration at Section 7 agencies. Through active collaboration with Demos and Project Vote, the state quickly increased its Section 7 voter registration rate from 3 percent to 10 percent. Over the course of the partnership, North Carolina generated some 233,000 voter registration applications at Section 7 agencies, many more than would have otherwise been registered.

After a change in state leadership and Board of Election personnel in 2012, North Carolina again began to report dramatically fewer voter registrations at public assistance agencies. A field investigation conducted by Demos in conjunction with the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, Project Vote, and the Lawyers’ Committee confirmed that the state was falling out of compliance. Specifically, clients reported not being offered the chance to register and not seeing a voter registration question on forms, and several Section 7 offices lacked voter registration forms altogether. This time, no agreement could be achieved outside of litigation. Demos and partners sued the state, winning a preliminary injunction and ultimately forcing compliance through a court-ordered settlement agreement. Voter registrations at Section 7 agencies have improved once again.

Ohio: Litigation and Sustained Change

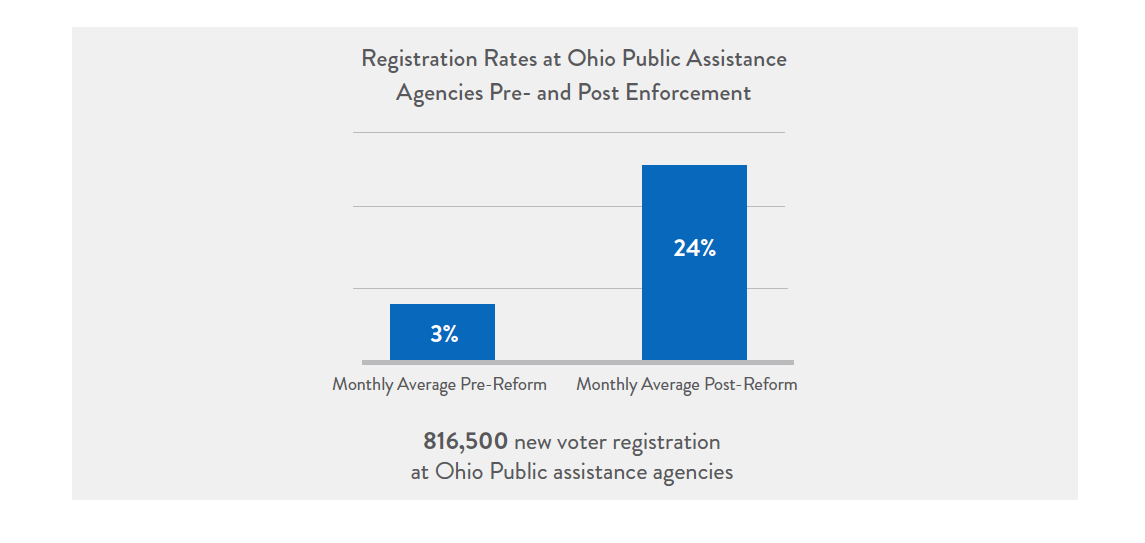

In 2005, Ohio’s Section 7 agencies were registering just 3 percent of eligible clients to vote. After a 2006 notice letter failed to prompt change, Demos and partners opened litigation against the state for non-compliance. As a result of the litigation and subsequent settlement agreement, Ohio improved its Section 7 registration rate from just 3 percent to nearly 25 percent of all eligible clients. Between January 2010 and June 2016, approximately 816,000 Ohioans interacting with public assistance agencies applied to update their registration status or to register for the first time.

Ohio continues to address compliance with Section 7 of the NVRA. Through advocacy efforts, Demos and the ACLU of Ohio addressed compliance concerns in the Ohio Benefits Self-Service Portal (online) in 2018. In September 2018, the Ohio Department of Jobs and Family Services and the Ohio Department of Medicaid agreed to distribute voter registration forms, provide required NVRA disclosures, and offer assistance with completion of the voter registration forms. As more and more states transition to online portals for public assistance and health benefits, it is crucial that measures like these are implemented to ensure continued opportunities for voter registration.

DMV Registration: Another Critical Component of the NVRA

Section 5 of the NVRA, known as “Motor Voter,” requires that eligible persons be given the opportunity to register to vote when applying, renewing, or changing an address for driver’s licenses and non-driver identifications. In 2014, Demos began investigating compliance with this part of the law, bringing to light that many states were out of compliance with Section 5, and that the rates of voter registration through motor vehicle agencies varied dramatically from state to state. Demos estimated that improved compliance could generate millions of additional voter registration applications if states implemented better practices.

The goal of Section 5 of the NVRA is to allow people to register to vote with minimal effort while completing a covered transaction at the DMV. Voter registration is integrated into the transaction form and involves only the additional steps of choosing a political party affiliation, reviewing the eligibility qualifications, and signing a certification of eligibility. In addition, the law requires that changes of address be automatically updated for voter registration purposes unless the voter indicates that the change of address should not apply to voter registration. This “opt-out” system is a vital protection for ensuring that voters are not dropped from the rolls when they move.

Since 2015, Demos, other advocates, and the Department of Justice have worked in a variety of states to improve voter registration at DMVs. Through advocacy, demand letters, and litigation, Demos has helped improve compliance in California, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Oklahoma, and has active efforts in Arizona, Missouri, and other states. The Department of Justice has successfully intervened in Alabama, Connecticut, and New York. After 3 years of enforcement activity, our interventions have produced encouraging results. In all states where data were available, the monthly average of voter registrations produced by the DMV increased dramatically.

Connecticut, for example, adopted comprehensive reforms and improved its monthly number of voter registration applications by 900 percent. In California, advocacy by Demos, Project Vote, and the ACLU of Southern California for improvements in Section 5 compliance helped move the state to implement automatic voter registration, and the number of voter registration applications at DMVs has skyrocketed. During the 2013-2014 election cycle, before advocates intervened, 854,000 Californians registered or reregistered to vote through DMVs. In the just over six months between automatic voter registration implementation in late April 2018 and the end of October 2018, 1.9 million Californians registered or re-registered to vote at DMVs, well over twice as many as were registered at DMVS during the entire 24 month election cycle of the last midterm elections.

Moving Forward: Recommendations for Realizing Full Voter Registration, the Goal of the NVRA

Progress in voter registration since the passage of the NVRA—and particularly in reducing the registration gap—is undeniable. However, even more can and should be done to achieve the promise of the NVRA and to fully close the registration gap for low-income communities and communities of color. There are several ways states can improve access to voter registration and expand the impact of the NVRA:

Adopt automatic voter registration. One important means for strengthening voter registration opportunities through public assistance offices is to incorporate automatic voter registration (AVR) in public assistance agency transactions. AVR works by ensuring that persons whose eligibility can be verified through existing state data sources (for example, data on file with driver’s license agencies) will be automatically registered to vote when they apply for services from the agency, unless the eligible individual affirmatively declines registration. To date, 15 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws or administrative procedures providing for automation of voter registration in some form. Only a few states, however, have included the option of automatic voter registration through agencies beyond the DMV. State Medicaid agencies may be a particularly attractive target for incorporating AVR because they serve a large population and because the record-keeping and eligibility procedures used for Medicaid applications lend themselves well to the goal of identifying eligible persons and seamlessly adding them to the voter rolls.

Use technology and design to upgrade public agency voter registration. By streamlining agency processes with up-to-date technology, public agency voter registration can be “nudged” in the right direction. The most significant first step in this regard is for a state to establish electronic transmission of voter registration applications from agencies to elections authorities. Additionally, when agencies implement new software and technology systems for processing their own benefits applications, they should also take advantage of the opportunity to make the voter registration component of the application as streamlined and user-friendly as possible. For example, such upgrades could incorporate automatic voter registration, as described above. Short of that, upgrades could create integrated voter registration applications that incorporate voter registration into existing forms clients complete when applying for benefits through public assistance agencies, similar to the forms used at DMVs (as mandated under Section 5 of the NVRA). Additionally, agencies should consult with designers who have experience in creating forms and instructions that are accessible and understandable to the public. This should include usability studies among agency clients to confirm that the forms and instructions will be understood as intended.

Strengthen procedures for NVRA compliance. In addition to expanding AVR to public assistance agencies and leveraging technology and design, states should take simple but important steps to ensure compliance with the NVRA by public assistance agencies. Specifically, states should:

- Appoint a state-level NVRA coordinator for each agency and local coordinators for each local office.

- Review procedures to ensure voter registration policies and procedures are in compliance with the NVRA.

- Ensure that the opportunity for voter registration remains clear, straightforward and accessible for online, mail, and telephone transactions as well as for in-person transactions.

- Provide regular training and easy availability of voter registration policies and procedures to frontline agency employees.

- Include compliance with voter registration responsibilities as part of the annual review for both frontline and supervisory agency employees.

- Ensure adequate supply of voter registration applications and voter preference forms for each office.

- Track and publicly report the numbers of covered transactions and voter registration applications generated at each office, and require NVRA coordinators to monitor data to spot and respond to significant drops or changes in voter registration numbers that could reflect compliance problems.

Expand voter registration to additional agencies. The NVRA specifically directs states to designate additional agencies and offices as voter registration sites, but few states have been creative or expansive in their approach to doing so. Many of the government and non-governmental institutions people interact with on a daily basis could easily serve as registration agencies, which would benefit everyone and especially make a difference for low-income communities. Potential additional places to offer voter registration include:

- Public housing agencies

- Prisons, jails, probation and parole offices, and re-entry agencies

- Departments for the aging

- Youth and community services agencies

- High schools, community colleges, and other institutions of higher education

- State licensing offices, e.g. occupational licensing offices, marriage licensing offices, etc.

- Federal agencies such as veterans affairs’ medical services offices, Indian health services, and USCIS (in its conduct of naturalization ceremonies)

- Non-profits that provide services to low-income communities, including homeless shelters and community medical clinics.

Enact additional policies that expand voter registration. Agency-based voter registration, of course, is not the only policy with the potential to increase voter registration. Policies such as same-day and Election-Day registration, online voter registration, and pre-registration of 16-and 17-year-olds, among others aimed at expanding the electorate, can also play an important role.

Conclusion

The National Voter Registration Act has brought millions of new Americans into the political process since its passage a quarter of a century ago. In lowering one of the highest barriers to voting—registration—the NVRA has helped to close gaps in civic participation between communities and, in turn, made our democracy more accessible, more equitable, and stronger. Section 7 of the Act plays a particularly important role in making registration accessible to low-income communities and communities of color, 2 constituencies that have faced barriers to voting since the nation’s founding. Moving ahead, states should adopt automatic voter registration and other policies that make registration more accessible, improve technology and design of voter registration at public agencies, strengthen procedures for NVRA compliance, and expand agency-based voter registration to additional agencies. While there is more to do to bring the reality of our democracy in line with our ideals, the significant and enduring progress of the NVRA should be a reference and a guide for the work ahead.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Ford Foundation, the Open Society Foundation, and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. Demos is also grateful to Douglas R. Hess for his substantial contributions to this report and to Lisa J. Danetz and Sarah Brannon for their advice and review. Finally, we would like to thank Connie Razza, Chiraag Bains, Mark Huelsman, and David Perrin for their contributions to the production of the report. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.