Introduction and Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically altered the way Americans access the ballot box, with millions more Americans expected to vote by mail compared to previous election cycles. While expanded voting by mail (VBM), also called absentee voting, is a necessary and safe tool to help voters who face barriers to in-person voting, it does not eliminate systemic, and often intentional, hurdles Black voters confront when casting their ballot. In the same way that COVID-19 has exposed long-standing racial inequities in our health system and economy, it is also revealing the structural cracks in our democracy. For example, Black and brown communities face burdensome requirements in getting a ballot, and are more likely than white voters to have vote-by-mail ballots rejected. At a time when many are experiencing housing instability, the need for a permanent address often makes it more difficult to register and receive an absentee ballot. The COVID-19 crisis has not only exacerbated long-standing inequities, it has also created new barriers that our lawmakers must address before the general election.

Prior to this pandemic, white voters used mail-in ballots with greater frequency than Black voters. In the November 2018 elections, nearly a quarter (24 percent) of white voters voted by mail nationwide, compared to only 11 percent of Black voters who voted by mail. These trends continued in some of the 2020 primary elections as well. For example, in several cities in Wisconsin and Ohio, predominantly white neighborhoods applied for absentee ballots at higher rates compared to predominantly Black neighborhoods; unsurprisingly, this led to significantly higher voter turnout in predominantly white neighborhoods compared to Black neighborhoods. Further, existing slowdowns in U.S. mail delivery and the Trump administration’s threatened cuts to the postal service could prevent Black and brown voters, who are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, from sending in their ballots by the respective deadlines.

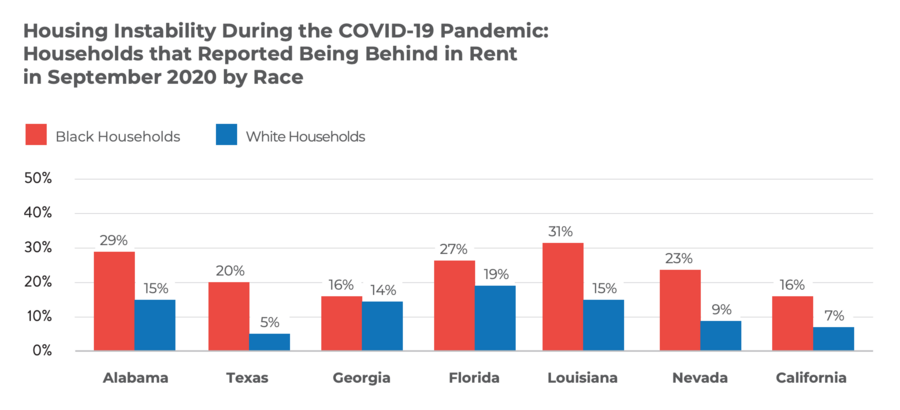

While some states have expanded their absentee ballot eligibility and procedures in response to the pandemic, other states have retained strict vote-by-mail eligibility criteria and requirements for returning a mail-in ballot. Voters face confusing absentee ballot eligibility requirements in states like Texas, and strict notary or witness requirements in states like Alabama, which pose more barriers for voters of color who have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and have a greater need to quarantine to keep their families and loved ones safe. New procedures in states that will allow all registered voters to vote by mail have not eradicated the hurdles that stem from housing instability. For example, Nevada will send “active registered voters” absentee ballots, but will not send them to “inactive” registered voters (voters who had election mail returned as “undeliverable” and did not return a letter to confirm their voting address.) The housing and eviction crisis is disproportionately impacting Black communities nationwide: according to recent Census data, 22 percent of Black households reported that they were not up to date on their rent payments, compared to only 9 percent of white households nationwide. In Nevada, the voters who have recently moved or been evicted, and therefore could not get election mail or return official election mailers, will be placed on the inactive list and will not automatically receive an absentee ballot. Instead, voters without a stable address will need to show up to the polls to vote and potentially risk their health or face voter intimidation, long lines, or other forms of voter suppression.

Black Futures Lab has been actively engaging with voters in “Black to the Ballot States,” which include Alabama, Texas, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, Nevada, and California. Below, we provide an overview of the vote-by-mail eligibility criteria in the Black to the Ballot states and highlight the hurdles that Black voters may face. Many local jurisdictions, elected officials, and courts in these states still have time to amend vote-by-mail procedures—and they must do so immediately. These immediate reforms include expanding eligibility for absentee ballots, extending registration deadlines and instating same-day registration, extending deadlines to return ballots, and giving voters the ability to contest or appeal their rejected ballots. At the same time, the long-term work of building an inclusive democracy that works for all voters will require community organizing, power- and movement-building, and deep community engagement.

From Confusing Eligibility to Housing Instability, Black Voters Face Hurdles to Voting Absentee

Black voters face hurdles at every step of the vote-by-mail process: from unclear eligibility criteria to strict rules for returning and counting absentee ballots, the pandemic has created more obstacles for Black voters to participate in our democracy. This section will focus on barriers specific to certain state policies in the Black to the Ballot states, including Texas’s unclear absentee ballot eligibility requirements, Alabama’s witness and notary requirement for returning an absentee ballot, and Nevada’s policy to not send ballots to “inactive” registered voters, despite the nationwide housing crisis that is impacting the state’s Black voters. Fortunately, there is still time to amend policies that can help make the 2020 general election more equitable and inclusive. These policies include expanding absentee ballot eligibility to all registered voters, waiving strict notary and witness requirements, and ensuring that voters can appeal if their ballot is not counted. In a global pandemic, these measures are necessary to ensure that systemic hurdles do not prevent communities from accessing the ballot box.

Texas: Unclear absentee ballot eligibility requirements and pending lawsuits sow confusion for Black voters

In many states, including Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Nevada, and California, all registered voters are eligible to apply for an absentee ballot. However, in Texas multiple lawsuits are still pending less than a month before the election, leaving questions about who is eligible for an absentee ballot. These complex eligibility requirements increase the risk that some voters will stay home due to safety concerns or other barriers, while others may expect an absentee ballot that never arrives.

In Texas, currently the only voters eligible for an absentee ballot must meet the following criteria: 65 years or older; disabled; out of the county on Election Day and during the period for early voting by personal appearance; or confined in jail, but otherwise eligible. COVID-19 related eligibility is still unclear based on the “disability” eligibility criteria in the Texas Election Code, which defines disability as a “sickness or physical condition” that prevents a voter from appearing in person without the risk of “injuring the voter’s health.” The Texas Supreme Court said that it is up to voters to assess their own health and determine if they meet the election code's definition of disability, but Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton wrote that fear of contracting COVID-19 does not amount to a sickness or physical condition as required by the Legislature to request an absentee ballot. This causes more confusion for Black voters, who have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 in Texas: according to data from the Texas Department of Health and Human Services, Black individuals comprised 17 percent of COVID cases, but only about 13 percent of the total population; in comparison, white individuals comprise 30 percent of COVID cases, but make up 79 percent of the population. Additionally, according to Census data collected in September 2020, nearly a quarter (24 percent) of Black Texans over the age of 18 reported being uninsured, compared to 11 percent of white Texans over the age of 18. Extraordinarily high medical costs often prevent uninsured individuals from seeking medical attention, and it will be more difficult for Black voters to prove they are eligible for an absentee ballot for COVID-19 related reasons. Although absentee ballot eligibility criteria in Texas is still being litigated, which leaves voters unsure of their voting options less than a month before the election, the Texas legislature and secretary of state still have time to expand absentee voting eligibility and increase the number of ballot drop-off sites before the general election.

Alabama: Strict return requirements add a barrier for Black voters even if all registered voters can get an absentee ballot

Even in states that allow all registered voters to apply for an absentee ballot, return requirements can still confuse voters. In Alabama, the return requirements are stricter than in some other states: absentee ballots include an affidavit that must be returned with the ballot, and the absentee ballot must either be notarized or 2 witnesses who are over 18 years old must sign it. Not only does the witness/notary requirement add extra layers of verification (beyond checking if a signature matches) for voters to ensure their ballots get counted, it runs counter to the goal of preventing close contact during a pandemic—which poses particular concerns for Black voters, who are especially at risk for COVID-19. As we have already seen in other states like North Carolina, these strict criteria may disproportionately lead to higher rejections of ballots from Black voters. Public health officials have published ample research that shows how COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted Black communities, and Alabama’s witness requirements are harder to fulfill for sick individuals who want to protect their health and the health of their loved ones. Alabama officials still have time to waive these restrictions and count ballots that are submitted with an affidavit and a signature; this will help ensure that voters who are sick or otherwise unable to find a notary or 2 witnesses over the age of 18 are not disenfranchised.

Nevada: Housing instability and the “inactive” registered voter list add another barrier for Black voters

The housing crisis disproportionately impacts Black voters in all Black to the Ballot states, but Nevada serves as a unique example of how the housing crisis creates obstacles for Black voters, even in a state that allows all registered voters to vote by mail. In Nevada, all “active registered voters” are sent an absentee ballot, but “inactive” registered voters are not sent ballots. As of September 2020, there were 227,266 voters on the inactive list, 74 percent of whom are in Clark County. Clark County’s electorate is about 13 percent Black and 63 percent white, and it is home to 93.48 percent of Nevada’s Black voting population: 188,852 Black voters reside in Clark County out of the 202,018 Black voters statewide. According to the Nevada secretary of state, registered voters are put on the inactive list after a piece of election mail is sent to the voter and returned as undeliverable, and the voter does not respond to a mailer to confirm their voter registration information. Remaining on the active list requires having a stable address to register to vote and receive mail, and the fact that the housing crisis is disproportionately affecting Black communities means it is possible that more Black voters are on the inactive list for not returning the mailers. In fact, according to Census data collected in September 2020, 23 percent of Black households in Nevada reported being behind on rent payments, compared to only 9 percent of white families. In a state like Nevada, where the 2016 presidential election was decided by a less than 3 percent margin of victory (around 27,000 votes), access to the ballot box during a pivotal election is imperative. The current process amounts to a less obvious, but no less dire, form of voter suppression. Although these barriers will make it more difficult for voters of color to access the ballot box, Nevada voters who are facing housing instability and were unable to receive an absentee ballot still have options on Election Day: they can register in person on Election Day if they need to update their address and registration information, and Nevada offers emergency absentee ballots for voters who are hospitalized and cannot come to the polls.

Housing instability adds another barrier for Black voters in voting by mail in all Black to the Ballot states

In an election increasingly dependent on voting by mail, housing instability and a wave of evictions will fundamentally alter the ability of voters to register to vote or receive and cast a ballot. Before the pandemic hit and pushed millions of Americans out of work, Black and brown populations were already overrepresented in the renting and homeless population, due to centuries of housing discrimination, racism in the labor market, and an increasing racial wealth gap. The pandemic has exacerbated housing instability and created another barrier to the ballot box for Black communities: according to Census data from September 2020, 22 percent of Black households nationwide reported that they were not up to date on their rent payments, compared to only 9 percent of white households. (See chart below for a breakdown of each Black to the Ballot state.) Additionally, during the same time, 14 percent of Black households reported having “no confidence” in their ability to make next month’s rent, compared to 7 percent of white households.

The requirement of a permanent address to receive a mail-in ballot amounts to voter suppression for the millions of Americans who are living in or near poverty and are now facing increased insecurity because of the pandemic. This voter suppression functions at every step of the voting process: not only are entire communities logistically unable to register to vote and receive a ballot if they have no home and no address, but families pushed to the economic brink are unlikely to have the time or inclination to deal with figuring out how to cast a ballot. Voters must provide an address and request a mail-in ballot before the election, and in some states like Louisiana, voters must apply for an absentee ballot with a secured address 2 full weeks before the election. Further, many voters who otherwise would have the opportunity to correct a missing or mismatched signature on a ballot would be impossible to reach if they are evicted from their primary residence. While states and the federal government have issued moratoriums on evictions, many have begun to expire, and a recent extension by the Centers for Disease Control contains narrow eligibility criteria to qualify for the extended eviction moratorium, and will not protect all renters impacted by COVID-19.

Impact/Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only exacerbated the systemic inequities that Black voters faced in previous election cycles, it has also created new barriers to the ballot box for Black communities trying to vote by mail during a pandemic. The inability to vote erodes the political power and the overall civic participation of Black communities. Those who are disenfranchised will have less power to hold their elected officials accountable for unjust policies, and less leverage to pressure these same officials to pass reforms that will help their communities. Voter suppression of Black and brown people and communities that have been devastated by the impact of COVID-19 will reverberate into every area of public policy, including housing, health care, economic stability, and criminal justice reform. Importantly, Black Futures Lab is working with grassroots groups and movement leaders to engage with voters to ensure that they can meet registration deadlines, have plans to vote by mail or in person, and can receive accurate information about absentee ballot eligibility and procedures.

In addition to the robust organizing work that BFL is doing in Black communities, government officials and policy makers still have a responsibility to protect the vote for Black and brown voters. Elected officials, secretaries of state, and Board of Election offices in various states can help ensure that the election is more equitable by instating the following measures:

- Increase VBM by expanding absentee ballot eligibility to all registered voters, but also offer safe, in-person voting options and accessible polling locations.

- Texas should expand absentee ballot eligibility to allow all registered voters to vote by mail. More than half of the states are allowing all registered voters to request absentee ballots, including Alabama, California, Nevada, Florida, and Georgia, and there is still time for Texas to expand eligibility criteria before the general election.

- All Black to the Ballot states should offer safe, conveniently located polling stations so voters who do not receive their absentee ballots, or did not qualify for an absentee ballot, can vote in person.

- Ensure all eligible voters have time to register to vote by extending deadlines and allowing voters to register on Election Day.

- All Black to the Ballot states should automatically send all registered voters absentee ballots and extend registration deadlines for those who want to vote by mail.

- Alabama, Texas, Georgia, Florida, and Louisiana should allow same-day voter registration, as California and Nevada already do.

- Provide prepaid return postage for all ballots and ballot applications.

- All jurisdictions in Texas, Florida and Alabama should either not require paid postage to return absentee ballots, or should provide voters with the required postage, as some—but not all—jurisdictions in these states currently do. Postage is either prepaid or not required in Louisiana, Georgia, Nevada, and California.

- Extend deadlines for mailing in and receiving ballots.

- Louisiana should extend their deadline for receiving ballots; the current deadline is 4:30 p.m. CST on the day before Election Day.

- All Black to the Ballot states should count ballots that have been received after Election Day to account for mail delivery. California will count ballots received by county elections offices no later than 17 days after Election Day.

- Extend deadlines for voters to contest or appeal rejected ballots, and process appeals efficiently.

- All Black to the Ballot states should instate efficient procedures to process appeals of ballot rejections, so rejected ballots can be remedied and counted.