COVID-19 Silenced Voters of Color in Wisconsin

Our analysis of 2020 election data shows how COVID exposed the flaws in our current election system and disproportionately affected Black and brown voters in Milwaukee. All cities and counties should take note to pass the necessary policies to protect voters.

The authors updated this piece with an addendum, below, on May 19, 2020

The spread of COVID-19 has had an unprecedented and disproportionate impact on Black and brown communities in the United States. While much of the policy discussion has rightly focused on COVID-19’s impact on the health and economic well-being of communities of color, decision makers must also urgently confront how the pandemic is silencing voters of color and harming our democracy.

Data show significant gaps in voter participation across racial groups in Wisconsin.

From recent headlines, you might think election concerns are overblown. Media reports after Wisconsin held its presidential primary on April 7 called voter turnout “extraordinarily high,” even though the election took place during a global pandemic. Unfortunately, this optimism misses an important and extremely troubling dynamic: Data show significant gaps in voter participation across racial groups in Wisconsin. As we have seen with the public health and economic fallout, the COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed the flaws in our current election system and disproportionately affected Black and brown voters.

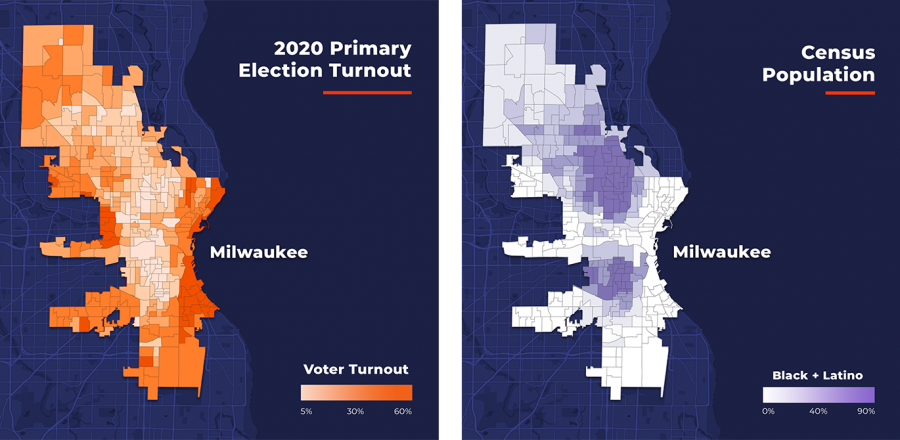

Nowhere was this more apparent than in Milwaukee. A new analysis of 2020 election data in Milwaukee City shows that wards with higher Black and Hispanic populations had significantly lower voter turnout compared to wards with a high percentage of white residents. Average voter turnout in Black and Hispanic wards was 30 percentage points lower than the average voter turnout in white wards.1

On April 7, thousands of Wisconsin residents risked their lives to vote in person. Many voters reported facing hurdles and health risks while attempting to vote, including people who applied for absentee ballots but did not receive them by Election Day, as well as people who were forced to wait in line for hours to vote. In Milwaukee, which is home to 60.32 percent of Wisconsin’s Black voters and 29.69 percent of the state’s Hispanic voters, officials decreased the number of polling locations from 180 to just 5. In the days leading up to the primary election, COVID-19 was spreading in Wisconsin, and it was particularly rampant in Black neighborhoods in Milwaukee—statistics from the first week of April show that African Americans made up almost half of Milwaukee County’s COVID-19 cases, and 81 percent of the county’s COVID-19 deaths.

While white wards had an average of 49 percent voter turnout, Black and Hispanic wards had an average of about 18 percent turnout.

Although a record number of absentee ballots were returned during the 2020 primary election in Wisconsin, overall vote counts do not tell us how COVID-19 is impacting access to the ballot box for different racial groups. While white wards had an average of 49 percent voter turnout, Black and Hispanic wards had an average of about 18 percent turnout.

In comparison to the 2016 primary elections, there was lower voter turnout across the board in 2020 among white, Black, and Hispanic groups, but the gap in voter participation between Black and brown communities and white communities remained large. In 2016, white wards had an average of 70 percent voter turnout, compared to 37 percent turnout in Black wards, and 42 percent turnout in Hispanic wards. The continuing disparities in voter turnout indicate that Wisconsin’s current absentee ballot and vote by mail procedures are clearly inadequate and do not alleviate issues with low voter turnout in Black and brown communities.

There is a dire and immediate need for all cities and counties to create measures that ensure eligible voters can safely and securely participate in future elections.

There is a dire and immediate need for all cities and counties to create measures that ensure eligible voters can safely and securely participate in future elections. Centuries of voter suppression and disenfranchisement have led to low voter turnout among communities of color. This compromises our democracy by silencing historically marginalized voters. Providing equal access to the ballot box is the only way to ensure that communities of color can exercise their right to vote and support policies that would benefit their communities, including better health care and economic safeguards.

Access to the ballot box in 2020 also has a lasting impact on future elections and our collective well-being. Due to unfair voter purge practices, voters of color will be more likely to be purged in future elections for failing to vote in this one. Black and brown communities will be unable to have a say in the policies that govern their lives, including housing, education, and other public services.

On May 4, Milwaukee Common Council passed a measure to send all registered voters an absentee ballot application and postage-paid return envelope for the general election. This is a step forward, but it is critical to go further by extending the deadline for receipt of absentee ballots, waiving the requirement that absentee ballots be signed by a witness, and prioritizing health and safety precautions for poll workers and voters with safe opportunities to vote in person—particularly for people without internet access or mail service, voters who need language assistance, and voters with disabilities. No one should have to choose between their safety and making their voice heard. This is the moment to pass policies that safeguard voters. Failing to do so will allow the continued disenfranchisement of Black and brown voters.

Addendum

We ran correlations at the ward level, using demographic data estimated from Census data and turnout data available from the City of Milwaukee. We found that as the percentage of Black or Hispanic residents in a ward increased, we saw a lower turnout rate. The opposite was true for white residents, where a higher population was correlated with a higher turnout rate. These correlations were statistically significant. For example, when we looked at the most extreme wards, or the wards with the highest percentage of one racial group, we found larger disparities in voter turnout in 2020: Ward 243 is about 95 percent white and had 59 percent voter turnout, while Wards 147 and 229, which are about 98 percent Black and 82 percent Latino, respectively, had a 15 percent turnout.

To illustrate our findings for this piece, we additionally conducted a homogeneous precinct analysis. When we compared the most homogenous wards in Milwaukee City, or the wards with the most residents from a racial group, we saw a notably large disparity in voter turnout in 2020 among racial groups.

Results are robust. We reported the average turnout using the top 3 percent of precincts with the highest percentages of each racial/ethnic group. Using that threshold, average voter turnout in Black and Hispanic wards was 30 percentage points lower than the average voter turnout in white wards. We relaxed that threshold to include the top 30 percent of precincts, and found that the disparity with white voters is still 17 points for Black voters and 13 percent for Hispanic voters. These findings echo the statistical correlations.

- 1We conducted a homogenous precinct analysis. Homogeneous precincts are precincts in the top 3 percent in terms of percentage for a racial/ethnic group. The white homogeneous precincts would be the 3 percent of precincts that have the highest percentage of white residents. The process is repeated separately for Black and Hispanic wards.