Introduction and Summary

For centuries, states have denied Black and brown voters the same rights to vote as their fellow citizens. Decades of policies and practices have contributed to the disenfranchisement of Black and brown Americans, including residential redlining, the criminal legal system, racist voter ID laws, voter purges, and modern-day poll taxes. This year, given the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic crisis, Black and brown voters face new barriers to democratic participation, including confusing rules, poll closures, and a massive wave of evictions that can jeopardize the ability to reliably receive and return mail-in ballots.

Although nowhere near exhaustive, this list of voter suppression tactics lays a foundation for understanding the conditions Black and brown voters encounter as they seek opportunities to participate in America’s democratic process in an election year unlike any we have seen. Our research finds that the COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed how Americans are accessing the ballot box—and is exposing systemic barriers that continue to keep Black and brown voters from participating in an election that is increasingly reliant on voting by mail.

To balance civic responsibility with protecting their health, growing numbers of Americans are opting to vote by mail, often known as “absentee.” The 2020 Ohio primary election, for example, was conducted entirely by mail over a months-long process that concluded on April 28th.

Expanding the ability to vote by mail should be one of several ways that policymakers guarantee a truly inclusive election. And while a cursory glance at voter turnout numbers may offer the comforting impression that overall voter turnout is up and more people are voting by mail this election cycle, the statistics rarely provide the substantive depth necessary to understand the barriers that communities of color face when accessing the ballot box. Indeed, new data reveal that our democracy may become even more unrepresentative.

As we discussed in our previous dissection of primary elections in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, looking at an analysis of overall voter turnout paints a limited picture. Many media outlets reported that voter turnout in the recent Wisconsin primary was “extraordinarily high,” but our breakdown based on race showed that voter turnout in Black and brown neighborhoods was significantly lower than turnout in white neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

New data tell us that Wisconsin is not an isolated example, and the same historic economic and political inequalities also affect whether Ohio’s Black and brown voters can engage in an election that is increasingly reliant on voting by mail. While overall primary turnout in Ohio fell between 2016 and 2020, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic and to an uncontested Republican presidential nomination and a Democratic race that had largely been decided, we still saw deep disparities across race.

In Cuyahoga County, Ohio, which includes Cleveland, voters in predominantly Black and brown communities were less likely to request and return an absentee ballot than voters in predominantly white communities. While this is due to a number of historical and policy reasons dating back many decades, the effects remain significant today.

We collaborated with Dr. Megan Gall and Dr. Kevin Stout at All Voting is Local to conduct an analysis of voter turnout in Ohio’s primary. Our analysis of the county’s 2020 primary, using Census data and data from Cuyahoga County Board of Elections, finds large disparities in absentee ballot request rates and voter turnout between predominantly white and non-white neighborhoods:

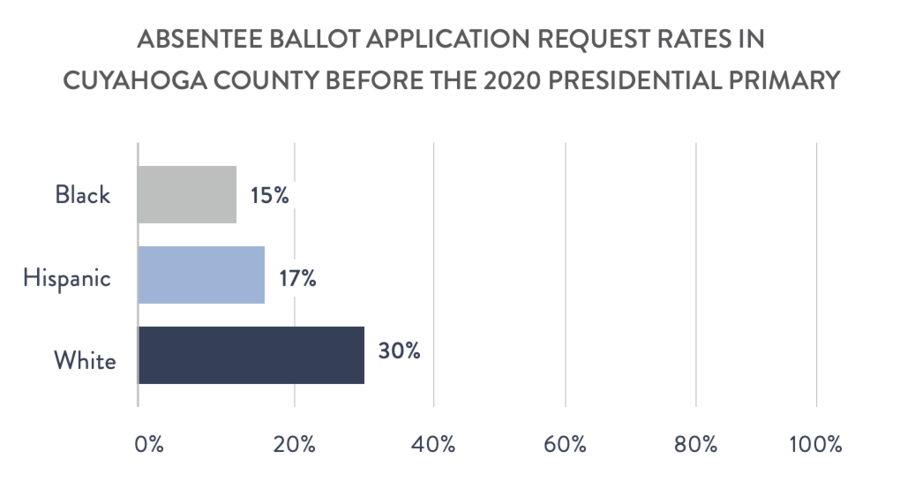

- A quarter of Cuyahoga County’s registered voters requested absentee ballots, but, on average, areas with larger Black and Hispanic populations had significantly lower absentee ballot request rates than areas with whiter populations— white neighborhoods in Cuyahoga County had a 30 percent absentee ballot request rate in the 2020 primary, while Black neighborhoods only had a 15 percent request rate, and Hispanic neighborhoods had a 17 percent request rate.

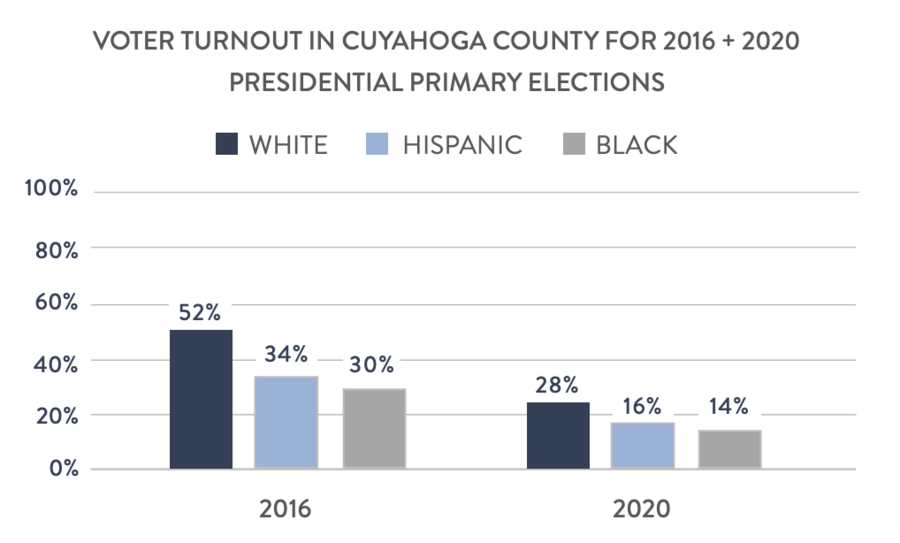

- Voter turnout among these groups was similar: white neighborhoods had a 28 percent turnout, while Black and Hispanic neighborhoods had 14 and 16 percent turnout, respectively.

In short, we cannot assume that voting by mail will erase, or even begin to shrink, disparities that have long existed in our democracy. Barriers to voting prevent Black and brown communities from electing officials who will fight for policies that address their needs and reflect their experiences in areas like policing, health care, education, housing, voting access, and employment.

In Ohio, low voter turnout puts voters at a higher risk of being purged from the voting rolls[.]

But there is also something more pernicious at play. In Ohio, low voter turnout puts voters at a higher risk of being purged from the voting rolls, due to a strict state rule that allows for the removal of those who do not cast a ballot in 2 federal elections. In 2018, the Supreme Court upheld an Ohio law that allows the state to purge voters who do not vote in 2 federal elections and do not responding to a “mailer/confirmation notice,” which are sent to the address used for registration. Research indicates that Ohio’s “use it or lose it” rule has a disparate impact on historically marginalized voters, and factors that impede access to applying for an absentee ballot have put these voters at a greater risk of being purged. Although states should not purge voters for inactivity 90 days before a federal election, and thus no additional voters are expected to be dropped from the rolls before November, this still puts Black and brown voters at a higher risk of being purged for future elections, especially if they cannot access a ballot for the November 2020 election.

In Cuyahoga County, Black and Latino Areas Cast Fewer Absentee Votes in the 2020 Primary

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, on March 25th, the Ohio House and Senate passed a bill that mandated Ohio's primary to take place via absentee voting. More than 1.9 million Ohio voters requested absentee ballots for the primary election, which was a 421 percent increase from absentee turnout in the 2016 primary. However, to apply for an absentee ballot, Ohio voters had to complete a detailed application, pay for postage, mail it to their county board of elections, and ensure it was received before the deadline. Secretary of State Frank LaRose and the Ohio Association of Elections Officials expressed concerns that the timeline in the bill was tight, and voters might not receive their ballots in time. Voter advocacy groups also critiqued the cumbersome application process, and noted that the compact timeline to request, receive, and submit a ballot was woefully inadequate. Ohio voters had to either pay for postage, or travel to the board of elections headquarters to return their application before the deadline, and then wait to receive their ballot in the mail. Advocates also protested the state legislature’s failure to offer meaningful in-person voting options for voters who did not get an absentee ballot on time or who prefer or need to vote in person, such as people experiencing homelessness, domestic violence survivors, and those voters with disabilities for whom in-person voting provides a private and independent way to vote.

We analyzed the effect on Black and brown communities in Cuyahoga County, which is home to Ohio’s largest Black voting base.

Those fears were realized when voters reported receiving absentee ballots after the election—if they received them at all. We analyzed the effect on Black and brown communities in Cuyahoga County, which is home to Ohio’s largest Black voting base. Cuyahoga County’s electorate is roughly 29 percent Black and 66 percent white, while Ohio’s total electorate is about 12 percent Black and 84 percent white. A quarter of Cuyahoga County’s registered voters requested absentee ballots (215,790 applications), but areas larger with Black and Latino populations had significantly lower absentee ballot request rates than areas with whiter populations. While white neighborhoods in Cuyahoga County had a 30 percent absentee ballot request rate in the 2020 primary, while Black neighborhoods only had a 15 percent request rate, and Hispanic neighborhoods had a 17 percent request rate.

Based on the gap in application rates by racial group, it is unsurprising that there were large differences in turnout between Black and Latino homogeneous precincts as compared to white homogeneous precincts in Cuyahoga County, where about 90 percent of absentee ballots were returned and counted for the 2020 primary. Overall, Ohio had about a 21 percent voter turnout in the 2020 primary election, compared to 44 percent turnout in the 2016 primary.

In the 2020 primary, voters in primarily white neighborhoods of Cuyahoga County were nearly twice as likely to return an absentee ballot and have it counted as voters in majority Black neighborhoods. While white neighborhoods had a 28 percent turnout rate, Black neighborhoods had a 14 percent turnout rate and Hispanic neighborhoods had a 16 percent turnout rate. In comparison, in the county’s 2016 primary elections, voter turnout was higher for all groups but disparities were still apparent: white neighborhoods had a 52 percent turnout, while Black neighborhoods had a 30 percent turnout, and Hispanic neighborhoods had a 34 percent turnout.

Housing Instability May Play a Role in Vote Suppression

Black and brown communities are more likely to experience housing insecurity because of racist housing policies and a widening racial wealth gap.

We may continue to see deep racial disparities in mail-in voting in 2020, due in part to one requirement: to apply for an absentee ballot, an individual must provide a residential mailing address. Black and brown communities are more likely to experience housing insecurity because of racist housing policies and a widening racial wealth gap. The pandemic has further exacerbated this challenge, creating massive job losses that leave people across the country, particularly renters, unable to pay for their housing. In Ohio, according to a Census survey on the impact of COVID-19, 19 percent of white renters reported not paying their rent or deferring their rent, compared to 42 percent of Black renters and 46 percent of Hispanic renters.

To temporarily alleviate the national eviction crisis, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (or CARES) Act, adopted in March, included a 120-day moratorium on evictions. The moratorium prevents landlords with federally backed loans from initiating eviction proceedings and from charging fees or penalties until July 25, 2020. This temporary moratorium will prevent housing instability for some residents for 120 days, but it does not address the root causes of housing instability for Black and brown communities, nor does it address how housing instability will be exacerbated for these communities because of the impact of COVID-19.

In Cuyahoga County, ending the eviction moratorium could have a disproportionate effect on Black voters. According to 2018 ACS 1-year estimates, 45.8 percent of renter-occupied housing units in the county were occupied by Black residents (105,253 Black renter-occupied housing units). If a portion of these disproportionately Black renters lose their housing, they may also lose the stable residential address needed to vote by mail.

Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of Barriers to the Ballot Box

A lack of access to the ballot box, whether in person or via the mail, has lasting implications on future elections and each voter’s ability to vote for policies that benefit their community. Black and brown voters already faced hurdles, such as inaccessible polling locations, no time off work to vote, no childcare, and/or no public transportation, that prevented them from having their voices heard. And we now know that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on Black and brown communities, making it urgent that policymakers do everything to conduct inclusive, safe, and fair elections that address the historic and current barriers voters of color face. In Ohio, low voter turnout is particularly damaging to marginalized voters because of the state’s “use it or lose it” voter purges.

When examining the disparities between Black and brown voters and their white counterparts, it’s easy to dismiss the difference as an enthusiasm gap or consider it a one-time problem caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As with so many areas of society, COVID-19 did not create the confluence of events that disenfranchise Black and brown communities; it merely exposed them. In the small window of time that we have between the primary and general elections, lawmakers and election officials in Ohio have an obligation to act immediately and ensure equity at the ballot box.

Ohio will be sending all registered voters an absentee ballot application for the general election, but this does not fully address the issues with low absentee ballot application rates and turnout among Black and brown voters. Ohio and other states need a comprehensive plan to ensure that every citizen’s path to the ballot box is unimpeded. Such a plan should remove barriers to voting by mail, from eliminating burdensome requirements to providing postage-paid return envelopes well in advance of voting. But the plan must also include safe options for in-person voting and creating robust systems and voter education efforts for online and same-day voter registration. Thus far, voting by mail has not solved or reduced disparities in voter turnout. Improving it is vital for the health of Ohio’s, and America’s, democracy.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Dr. Megan Gall and Dr. Kevin Stout with All Voting is Local for their quantitative analyses, research contributions and thought partnership on this paper.