Five Ways Higher Education Can Stop Failing Black People

It is time for colleges, states, and the federal government to prove their commitment to Black students with policy action—not just well-meaning statements and gestures.

In the past few weeks, hundreds of colleges and universities have released statements addressing the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, and other Black and brown lives that have been taken by the state or fellow citizens. Some institutions, like the University of Minnesota, have been galvanized by this moment and taken concrete steps to reduce or end their relationship with local police. Other schools have formed task forces and hosted discussions on how they can, in theory, contribute to lasting social change. That these institutions are grappling with such questions during a global pandemic and domestic depression speaks to both the urgency and the cultural power of this moment and movement.

Statements and actions are two very different things.

Statements and actions are two very different things, however. This moment, if we are honest, will force us to ask some hard questions that move beyond sympathy or support. It should force us to recognize the fraught relationship between race and higher education, and ways that our system of postsecondary education too often perpetuates the social and economic exclusion of Black families, students, and faculty.

If we truly believe this to be a time to prove commitments to Black and brown students, then colleges, states, and the federal government have the choice to do something fundamentally different. Here are 5 ways they can start.

Policy Choice #1: Selective colleges should open their doors to Black students.

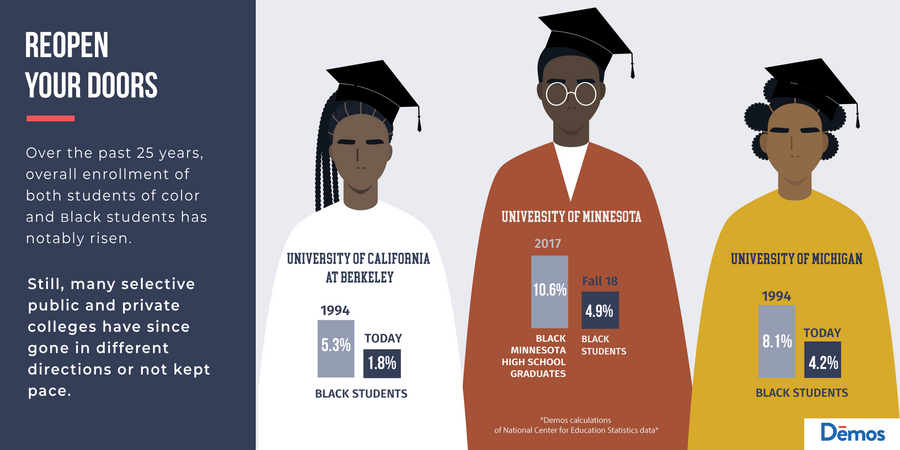

Over the past 25 years, while the overall enrollment of students of color and Black students has risen, many selective public and private colleges have gone in different directions or not kept pace.

For example, the University of California’s flagship campus at Berkeley, whose statement of solidarity with the Black community can be found here, has fewer than half as many Black undergraduates as it did in 1994. Twenty-five years ago, the undergraduate population was 5.3 percent Black; today it is 1.8 percent Black. At the University of Michigan, whose statement can be found here, 8.1 percent of the undergraduate population was Black in 1994; today it is 4.2 percent. At the University of Minnesota’s flagship campus, less than 7 miles from the spot of George Floyd’s murder, 4.9 percent of the undergraduate population was Black in the fall of 2018, despite the fact that 10.6 percent of the state’s high school graduates were Black in 2017-18.1

These dynamics persist for many reasons but at their core they reflect institutional and, in the case of public institutions, state priorities.

These dynamics persist for many reasons—rising prices, wealth disparities, and the dismantling of affirmative action, to name a few—but at their core they reflect institutional and, in the case of public institutions, state priorities. They are choices that can be unmade. As one example, California’s Board of Regents has taken a first step by advocating for the repeal of the state’s affirmative action ban. This is, of course, just a first step, and institutional leaders should not hide behind limitations on affirmative action as a reason for failing to enroll black students up to this point.

Save this infographic and share it on Twitter.

#2: Reward states that prioritize justice in their funding, and reward colleges that keep prices low and graduation rates high for Black students.

Federal policymakers have broadly decided that loans should be the primary way we finance college, despite the fact that debt has long been weaponized against Black and brown families. In addition, Title III and Title V funding is woefully insufficient to address the racial wealth and public funding disparities facing Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). State policymakers, by and large, have failed to fully restore cuts from the Great Recession that had a disproportionate impact on HBCUs and community colleges, which are more heavily reliant on public funding. Institutions like community colleges that more often reflect the racial and socioeconomic makeup of their state or community are not rewarded for doing so.

Meanwhile, there is no concerted federal effort to reward colleges that graduate or successfully transfer high numbers and high percentages of Black and Brown students. Colleges are not rewarded with extra federal funding, through the Pell Grant program or any other, for guaranteeing affordability, keeping net prices low, or eliminating borrowing for students, especially those from communities of color.

Instead, over the past decade, many states were implementing “performance-based” or “outcomes-based” funding.

Instead, over the past decade, many states were implementing “performance-based” or “outcomes-based” funding which prioritized increasing graduation rates, among other metrics. The result of these efforts, in some cases, was to make some institutions less racially and socioeconomically diverse. Another choice might have been to massively expand funding to the colleges that enroll and graduate high numbers of black students, or those that prioritize no debt as an outcome for black students. It’s a choice that could be made by states and Congress today.

#3: Reward schools, states, and municipalities that prioritize education over policing.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the deep recession, cities and states have been forced into difficult budget decisions. These decisions have, at least preliminarily, meant disaster for higher education. While the CARES Act provided $14 billion to colleges and universities to backstop some of these cuts and provide aid to students,2 the scope of cuts will likely be much higher. Local higher education funding is also likely to be decimated, affecting community colleges most acutely.

Yet even in a moment of budget crisis, there is room to prioritize Black people.

Yet even in a moment of budget crisis, there is room to prioritize Black people. For example, under Mayor Bill de Blasio’s FY2021 budget, the New York Police Department would see a cut of less than 0.4 percent, while the New York Department of Education would be cut by 3 percent. While the City University of New York—an engine of mobility for working-class students and the city’s Black and brown students—faces dire budget cuts, the city still prioritizes police funding.

Into the breach have stepped student leaders and activists, who are pushing colleges and states to rethink campus policing altogether. While the University of Minnesota was among the first to announce a partial end to their relationship with local police, students elsewhere are pushing administrators hard on where their campus dollars flow. In Washington, DC, students from American University, Catholic University, Gallaudet University, George Washington University, Georgetown University, Howard University, and University of the District of Columbia have all asked their institutions to end the relationship with the Metropolitan Police Department. The federal government could easily step in and reward colleges that move resources away from police and toward aid and student services.

#4: Prioritize faculty of color and leadership.

Research shows that a diverse faculty can have a positive impact on student success, especially for students of color. Yet our higher education system has moved slowly to expand opportunities for faculty and leaders of color. Five percent of college presidents are women of color, even though women of color make up nearly a quarter of the total enrollment in colleges and universities. While the percentage of faculty of color has ticked up slightly over the past few decades, that growth has largely come from those in adjunct, non-tenure track, and part-time positions. Even these gains are fragile: the budget cuts after the COVID-19 pandemic and recession are likely to fall most heavily on adjunct or contingent faculty.

These are institutional, and in some cases state, choices to have an unrepresentative faculty or allow diversity to be gained only from tenuous or low-pay jobs. There is no federal effort of note to incentivize institutions to hire more faculty of color. There is no good reason for this.

#5: Stop responding to the Black student debt crisis with indifference or modest reform.

Unmanageable debt for Black students is largely ignored because white graduates do quite well, in terms of earnings, debt payments, and other economic outcomes.

The move to a system of college financing that prioritizes loans over grants, or loans over generous per-student funding, has been a slow-rolling choice for decades. It is a move that has had catastrophic consequences for Black college students, who borrow more, default at higher rates, take longer to repay loans, and build less wealth than even non-college educated white families.

We should be frank about the drivers of this. There has long been a concerted, bipartisan push to increase college enrollment. During the 1990s and early 2000s, this allowed predatory institutions to expand and load up Black and brown students with debt. In the past decade, as the Obama administration and some states sought greater accountability in the for-profit college sector, many policymakers and higher education leaders have too often waved away the genuine anxiety about debt and rising prices, explaining that the average degree-holder tends to fare better in the job market.

They can do this primarily because white college graduates are likely to build hundreds of thousands of dollars in wealth—never mind that they also receive massive financial support from parents or grandparents—and can be lifted up as proof that, despite rising debt levels, things are not all bad.

It is a choice to look at a debt crisis in Black communities and respond with anything but comprehensive reform.

But it is a choice to look at a debt crisis in Black communities and respond with anything but comprehensive reform. It is a choice to take comfort in cutting higher education budgets, and barely increasing grant aid, knowing that the impact on white students will be relatively minimal. This is not asking institutions to move heaven and earth, and instead take concrete and achievable steps to make postsecondary education less risky for Black folks.

We find ourselves at a moment of reckoning around how our country addresses the relentless acts of violence against Black and brown Americans. It is a moment that calls for protest, anger, reflection, and deep listening, and above all, new thinking on how we design systems and institutions. It’s a choice to put out a statement, and another one altogether to build real, lasting change.