What do people mean by “money in politics” or “campaign finance reform”?

Running for office requires money—for staff, travel, TV ads, etc. In many countries, much of the cost of public elections is paid for by public funds, so the voters control the process and candidates are only accountable to their constituents. But in most places in the U.S., election campaigns are funded only with private money, most of it coming in the form of large checks from wealthy donors.

Many concerned citizens want to change the way election campaigns are funded so elected officials are more responsive to voters rather than donors. And many are also concerned that the billions of dollars special interests spend lobbying legislators skews our elected officials’ priorities.

Why is the role of money in politics a problem in the U.S.?

In a democracy, the size of a person’s wallet isn’t supposed to determine the strength of her voice. The principle of “one person, one vote” means we’re all supposed to have an equal say over the decisions that affect our lives. But right now the rich have more say than the rest of us.

Running for office in the U.S. typically requires raising lots of money from wealthy donors, and this means the “donor class”—those who can afford to give $1,000, $10,000, or even $1 million to campaigns—ends up with much more influence than the rest of us. These rich individuals and institutions even act as gatekeepers, using their money to decide who’s able to run for office, who wins elections, and what issues get attention from elected officials.

Is it getting better or worse?

The problem has been getting worse in two important ways. First, the cost of running for office is rising sharply, which means that people who aren’t rich themselves and don’t have rich friends or associates have trouble getting a campaign off the ground. To match the median winner in 2014, a candidate for U.S. Senate had to raise $3,300 every single day for six years. That’s really hard to do unless you’re bringing in $1,000 to $5,000 checks. Which leads to the next way the problem is getting worse: a greater percentage of the money is coming from a tiny fraction of the public giving big bucks. These large donors are whiter and wealthier than the rest of us, and have very different views on critical issues such as living wages and protections against Wall Street abuses.

What does the public think about all this?

The vast majority of Americans—regardless of party or ideology—think this is a serious problem and support a whole range of solutions. Three quarters of voters think wealthy companies and individuals have too much influence over elections, and this was a top concern in the 2016 election. More than 80 percent of Democrats and more than 70 percent of Republicans support limits on campaign spending.

What has Congress done to address the problem?

After the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, Congress passed a law that limited campaign contributions and spending, required disclosure, launched a system of public funding for presidential campaigns, and created the first agency to actually enforce the law, the Federal Election Commission (FEC). Unfortunately, the Supreme Court struck down spending limits; congressional inaction in the face of rising campaign costs has left the presidential system ineffective; and the FEC is hobbled by a structure that often leads to tie votes and lack of enforcement.

By 2002, corporations and other rich donors were finding ways around the law, so after the Enron scandal Congress tried again, banning unlimited “soft money” contributions to political parties as well as corporate and union spending on ads meant to look like advocacy around issues but actually intended to influence elections. But the Supreme Court struck down key parts of that law too.

What about states and cities?

States and cities have been leading the way on money in politics reforms, especially in recent years. States like Maine, Arizona, and Connecticut give public funding grants to candidates who show sufficient grassroots support, so they don’t need to depend upon wealthy donors. Cities such as New York and Los Angeles match small contributions with public funds, giving candidates the incentive to reach out to low- and middle-income constituents who can only afford to give $20 or $30. And Seattle recently created an innovative system making $100 in “democracy vouchers” available to every eligible voter to give to any candidate for city office. These programs can diversify the donor pool, and encourage more candidates of different backgrounds to run for office.

States have also passed contribution limits set at levels average Americans can afford to give. But these low-limits programs have been undermined by Supreme Court rulings opening the floodgates to unlimited spending by billionaires and outside interest groups. Strictly limiting candidates’ fundraising, but not fundraising or spending by outside groups, can result in candidates’ voices being overwhelmed by all the outside money. In addition, the Supreme Court has struck down some low limits directly.

What has been the role of the Supreme Court?

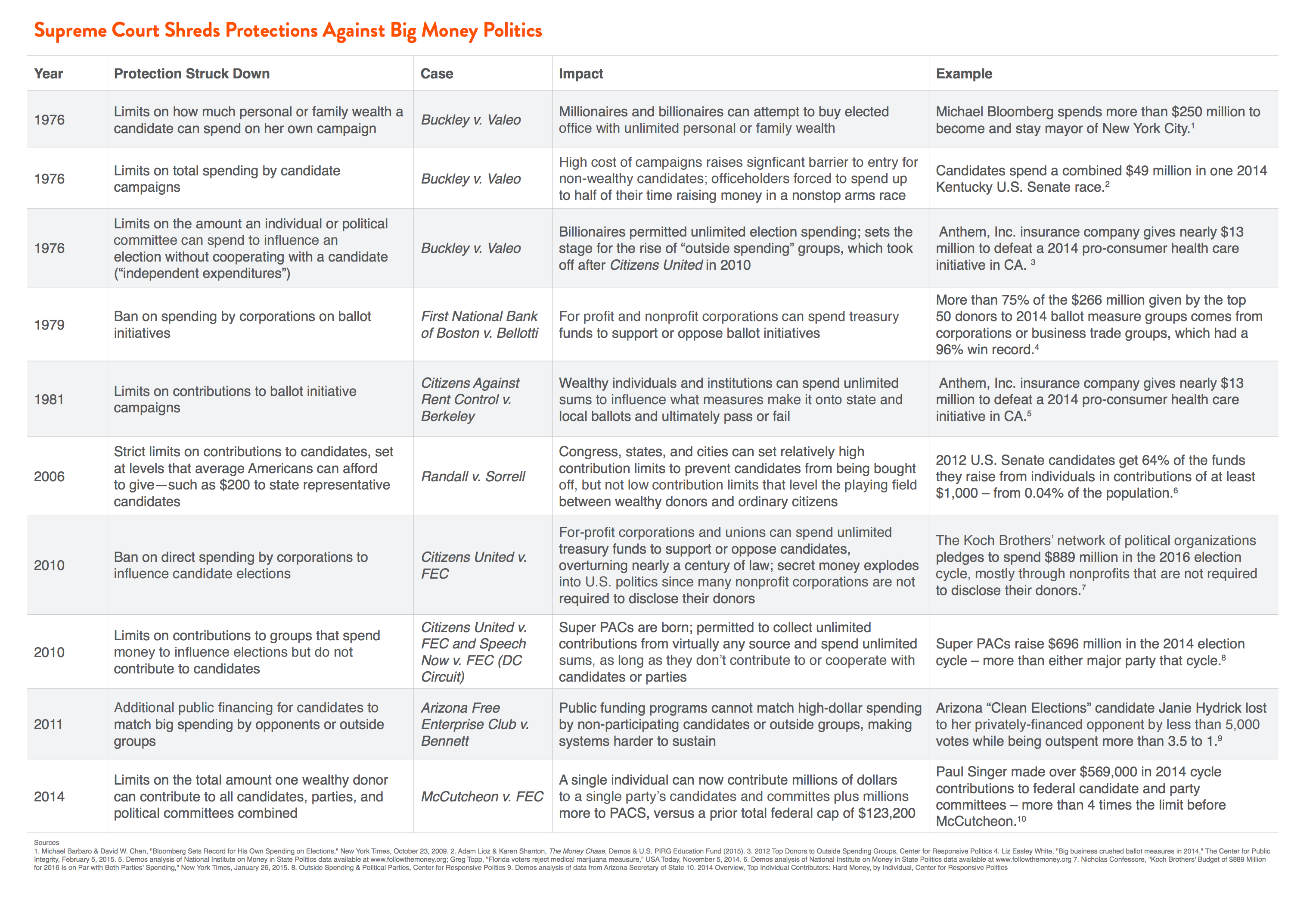

The Supreme Court has been the single biggest obstacle to creating a fair system. In 1976, the Court said that unlimited campaign spending is like free speech, and struck down key parts of Congress’ post-Watergate law. In the four decades since, the justices have gutted common-sense protections against big money time and again. The most famous case is Citizens United from 2010, but there have been plenty of others.

What kinds of laws has the Supreme Court struck down?

The Court has struck down a range of protections from limits on how much a wealthy candidate can spend on his own campaign, to bans on corporations helping to elect candidates who are good for their bottom lines, to limits on the total amount that a single wealthy donor can pump into the system in an election cycle. You can find a rundown of the most important protections the Court has gutted on the back of this FAQ.

Why has the Court been striking down common-sense protections against big money?

Back in the 1970s, the Court ruled that unlimited campaign spending is like free speech, which means that those with more money get more speech. The Court also ruled that the only reason we’re allowed to put any limits on contributions or spending is to fight corruption or its appearance. The justices said we’re not allowed to level the playing field between wealthy donors and the rest of us—even though our democracy is supposed to be based on equal citizenship.

More recently, the Roberts Court has said that we’re not even allowed to tackle systemic corruption or big donors getting increased access and influence—our laws can only target actual bribery of elected officials. We can’t pass a law unless we can show there’s a significant risk of someone being bought off. That’s why billionaires are allowed to spend as much money as they want to support their favorite candidates, as long as they don’t talk to the candidates about it; the majority of the Court claims that no discussion must mean no bribery.

But bribery isn’t that common in the U.S., and it’s not the primary way special interests and rich people get what they want from government. Using their contributions as leverage, big donors determine who can run for office, who has the best chance to win elections, and which issues get attention from legislators. But since none of that involves cash-for-vote exchanges, the Supreme Court finds nothing wrong with it and says we can’t limit big money to fight it.

What have been the consequences for our democracy?

The Court’s decisions in money in politics cases have distorted our democracy, stacked the deck in favor of the wealthy and against ordinary voters, and made a mockery of the one person, one vote principle. And because people understand this, rulings like Citizens United have reduced the public’s confidence in our system and the people who serve within it. In fact, 85 percent of Americans think we need to “fundamentally change” or “completely rebuild” our system for funding campaigns.

And for our economy?

Since the 1970s, the top 1 percent has monopolized the vast majority of the nation’s economic growth, while inter-generational mobility has stalled. The Court’s money in politics decisions have helped structure a society in which wealthy interests can freely translate economic might directly into political power, and write rules that keep themselves rich while the majority of Americans struggle to get ahead, or even stay afloat. The Court launched a vicious cycle of political and economic inequality, and a big-money political system that holds back our struggle for economic justice.

What about racial equity?

Centuries of state-sponsored oppression have created a huge racial wealth gap in the U.S., and our big-money system translates this inequality into political voice. The donor class is much whiter than the rest of America, and often pursues agendas that disproportionately affect people of color—such as rejecting strong investments in affordable college education. And the need to raise big money is a barrier to candidates of color running for elected office.

What difference could the next justice confirmed to the Court make?

The stakes couldn’t be higher. The Court is currently split 4-4 on money in politics, and many other issues. The next justice will decide whether we lose even more protections against big money (like the ban on contributions from corporations to candidates) or if we can actually turn the tide and end Super PACs, get corporate money out of our elections, and bring back reasonable limits on contributions. With a justice committed to core democratic principles, we can restore our pro-democracy Constitution, and finally get government that is truly of, by, and for the people.

What should senators know about a Supreme Court justice nominee’s views on money in politics before voting on his or her confirmation?

Every senator should ask the nominee: Is fighting bribery the only valid reason for limiting big money in politics, or do We the People have the power to enact common-sense protections so that Americans of all incomes, races, and backgrounds can run for office and have our voices heard?

Why is it important that we have Supreme Court justices who understand the Constitution gives us the power to protect our democracy from big money?

Right now we’re fighting big money with one hand tied behind our backs—because the Supreme Court has taken away some of our best weapons, such as strong limits on political contributions and spending. To tackle our nation’s biggest challenges—from climate change to economic and racial injustice—we’ll need to build a democracy where the strength of our voices doesn’t depend upon the size of our wallets. We can do that together, as long as the Supreme Court gets out of our way.