Executive Summary

Although each major party presidential candidate will likely break previous fundraising records, the big story of the 2012 election has been the role of Super PACs, nonprofits and outside spending generally.

Demos and U.S. PIRG Education Fund analysis of Federal Election Commission (FEC) data and secondary sources on outside spending and Super PAC fundraising for the first two quarters of the 2012 election cycle reveals:

Outside spending by organizations that aggregate unlimited contributions from wealthy individuals and institutions is playing a significant role in the 2012 election cycle, and much of it is not disclosed.

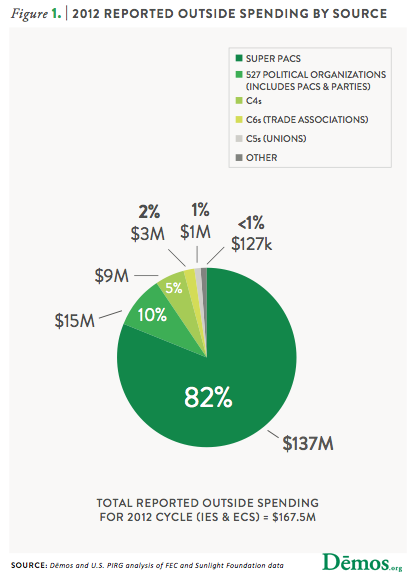

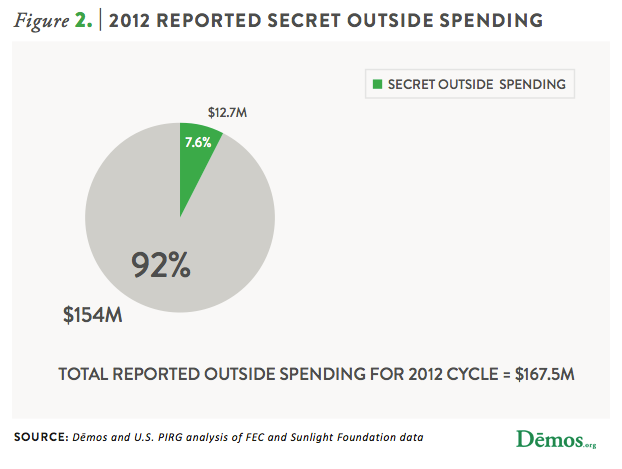

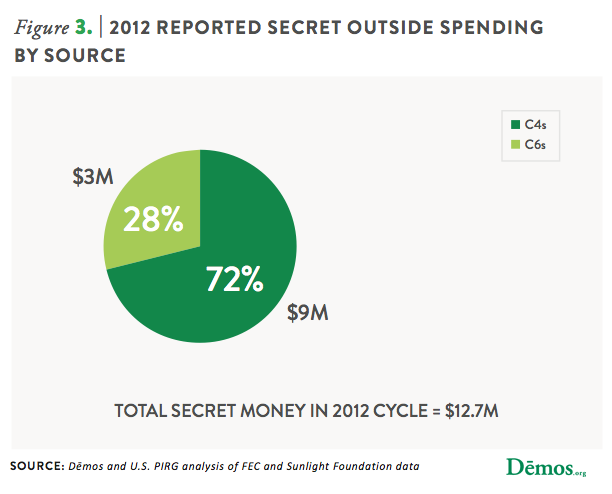

- Outside spending organizations reported $167.5 million in spending to the FEC. Of this, $12.7 million (7.6% of the total) was “secret money” that cannot be traced back to an original source.

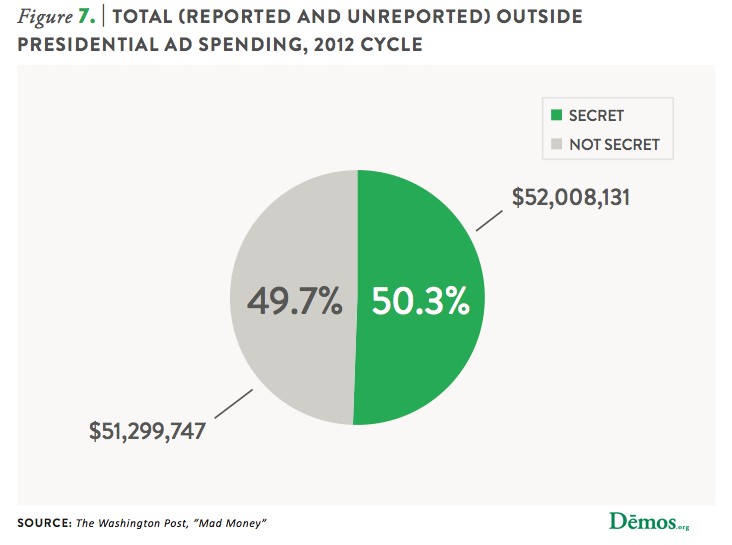

- But, because of gaps in reporting requirements, spending reported to the FEC is only part of the picture. When all types of outside spending on television ads related to the presidential race are taken into account, just over 50% of the spending has been by “dark money” groups that do not disclose their donors. According to Kantar CMAG data, the top four 501(c)(4) spenders on the presidential race have spent $43.3 million through July 1st on advertising in the presidential race alone, but our analysis shows these same groups have only reported $418,920 in spending collectively on all races to the FEC through June 30th. This means that these groups are currently reporting less than 1% of their total spending.

- The Top 5 outside spending groups have accounted for 58.5% of all outside reported spending in the 2012 cycle.

Super PACs continue to be tools used by a small number of wealthy individuals and institutions to dominate the political process.

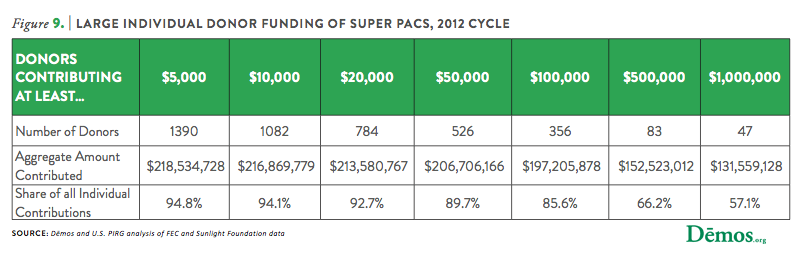

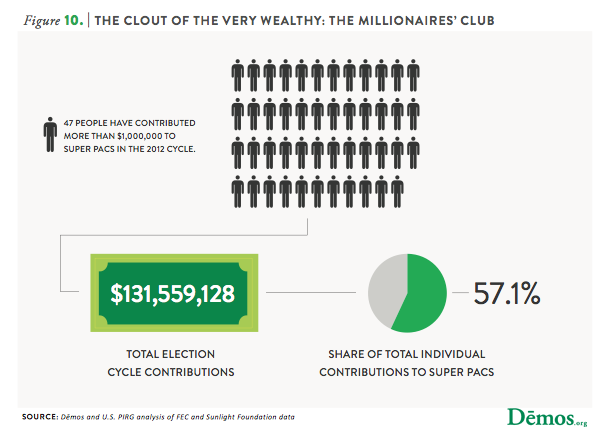

- Just over 57% of the $230 million raised by Super PACs from individuals came from just 47 people giving at least $1 million. Just over 1,000 donors giving $10,000 or more were responsible for 94% of this fundraising.

- Sheldon and Miriam Adelson have given a combined $36.3 million to Super PACs in the 2012 cycle. It would take more than 321,000 average American families donating an equivalent share of their wealth to match the Adelsons’ giving.

- For-profit businesses contributed $34.2 million to Super PACs, accounting for 11.0% of their fundraising. There are reasons to suspect business are contributing much more to nonprofit organizations and trade associations that do not disclose their donors.

Introduction

The Republican presidential primaries introduced the world to Super PACs—political committees empowered to raise unlimited funds from virtually any source and spend this money to influence U.S. elections. These “independent expenditure committees” were actually created back in 2010 as a result of a D.C. Circuit Court decision in the wake of Citizens United. They spent $65 million in the 2010 cycle. Yet few outside of Washington had heard of them before Sheldon Adelson gave $10 million to one and Stephen Colbert started his own.

Super PACs have fast become a favored tool for wealthy individuals and interests to drown out the voices of average citizens. At the end of the 2010 election cycle, there were 84 active super PACs. As of June 30, 2012 there were 220 active Super PACs, which have raised more than $312 million for the 2012 election. There’s even a Super PAC dedicated to ending Super PACs, proving the entity has truly arrived.

In February, we reported on the funding sources of Super PACs through 2011. With data now in for the first two quarters of 2012, fundraising trends for Super PACs continue to raise serious concerns for our democracy. The vast majority of Super PACs’ funds continues to come from a tiny minority of wealthy individuals giving tens of thousands, or even millions, of dollars. For-profit businesses continue to provide a significant portion of Super PAC funding. And, a small percentage of the money raised by Super PACs cannot be traced back to its original source.

But, Super PACs don’t have a monopoly on distorting our democracy. For all their problems, Super PACs have one significant virtue: transparency. They are required to report all of their spending on a real-time basis and all of their donors monthly or quarterly to the Federal Election Commission. As we move further into an election cycle that will almost certainly shatter all previous records for fundraising and spending, other, less transparent, forms of outside spending are coming increasingly to the fore.

Nonprofit “social welfare” organizations exempt from taxes under Section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code and trade or membership associations organized under Section 501(c)(6) are permitted to spend money to influence federal, state, and local elections, but are not required to disclose the identities of their donors or the amounts of their contributions.

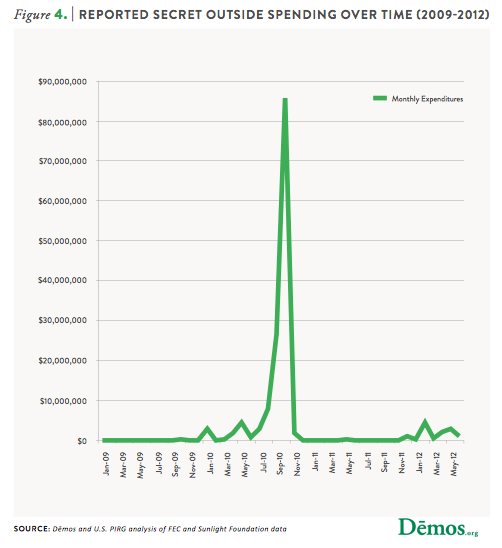

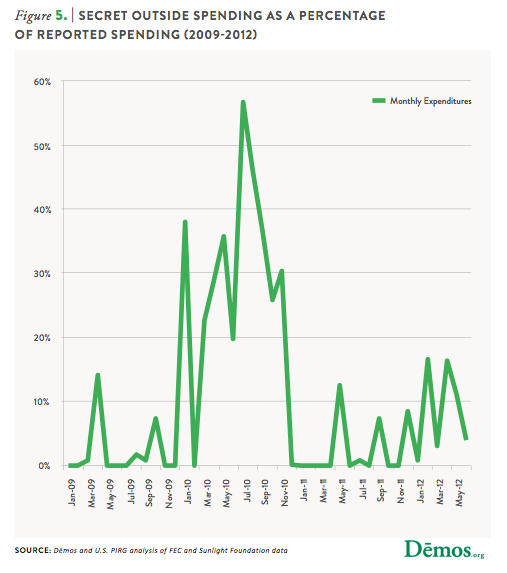

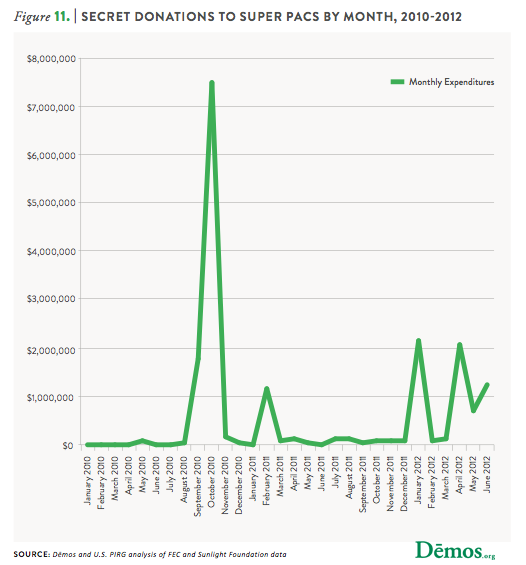

These “dark money” groups actually outspent Super PACs in the 2010 cycle by a substantial margin, and they are poised to have a significant effect on this year’s elections as well. But, we don’t have the full picture of secret spending in 2012 for two reasons.

First, if historical trends continue, secret spending will spike in the months immediately preceding the election. The data is not in for these critical final months, but in the following pages we report on trends from past years, which shed some light on what’s to come. Second, because of reporting gaps discussed in detail below, much of this spending is doubly-secret—not only do we not know the source of the donors, but the spending itself is not reported to the FEC or any other public agency.

Despite this incomplete picture, there is mounting evidence that nonprofits will again outspend Super PACs in 2012. In the pages that follow, we examine a cross-section of this evidence.

This report focuses on spending by outside, non-candidate groups attempting to influence federal elections. But, this is not because outside spending is inherently bad. There is nothing wrong with organized groups of Americans voicing their views about candidates and their positions on critical issues in the context of an election, as long as the strength of their voices has some relationship to the number of persons who support the views being expressed.

The reason that outside spending is currently distorting our democracy is that this unlimited spending is derived in large part from unlimited contributions. The vast majority of 2012 outside spending is being conducted not by grassroots organizations that are aggregating the power and voices of thousands or millions of people making small political contributions, but rather by a small number of organizations that aggregate the power and voices of a tiny minority of wealthy individuals, businesses, or interest groups contributing sums that are well beyond the reach of average-earning citizens.

One might think of today’s outside spending groups as megaphones for moguls and millionaires. The more money they pump in, the louder they’re able to amplify their voices—until a relatively few wealthy individuals and interests are dominating our public square, drowning out the rest of us.

This type of distortion is worse when much of the spending is secret, insulating big spenders from accountability and denying voters both critical information to make informed choices and a holistic picture of just how distorted the system is.

Candidate fundraising is distorted too—candidates have long raised the majority of their funds from a small minority giving $1000+ contributions. But candidate funding is limited and disclosed, and so in today’s campaigns, outside spending is where the distortion is most extreme.

This distortion violates our shared commitment to political equality and the principle of one-person, one-vote. It shapes a political system in which the size of a citizen’s wallet determines the strength of her voice.

What can be done to correct this distortion and create a democracy that is truly of, by, and for the people? The Supreme Court has caused much of the problem by turning the First Amendment into a tool for wealthy individuals and institutions to use to dominate political campaigns. This means that we ultimately need to take back the First Amendment—either by appointing justices who will interpret it properly, or by explicitly amending the Constitution. In the meantime, there is plenty that our democratically elected leaders can do to repair our distorted democracy. We provide specific policy recommendations after our analysis.

Reported Outside Spending

The following analysis details all of the money spent independently of candidates to influence federal elections that is reported to the FEC. As we note below, because of gaps in reporting requirements this does not provide the full picture of outside spending, or of outside spending funded through secret sources.

The top five outside spending organizations were responsible for 58.5 percent of reported outside spending thus far in the 2012 cycle.

Of the spending reported to the FEC, $12.7 million, or 7.6 percent was secret spending, not traceable to an original source.

Total Outside Spending Estimates

Known Unknowns and Unknowns Unknowns: Doubly-Secret Spending

We define “outside spending” here as spending intended to influence a federal election that is not conducted by or coordinated with a candidate for federal office. The three components of such spending are “independent expenditures,” “electioneering communications,” and “issue advocacy” that is in fact intended to influence elections. Unfortunately, current reporting standards are insufficient to describe the full picture.

An “independent expenditure” is defined by the FEC as an expenditure for a communication "expressly advocating the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate that is not made in cooperation, consultation, or concert with, or at the request or suggestion of, a candidate, a candidate’s authorized committee, or their agents, or a political party or its agents." An “electioneering communication” is any broadcast, cable or satellite communication that refers to a clearly identified federal candidate; is publicly distributed by a television station, radio station, cable television system or satellite system for a fee; and is distributed within 60 days prior to a general election or 30 days prior to a primary election for federal office. Any entity that conducts either of these two types of spending must report the amount of the spending and the candidate(s) supported or opposed to the FEC with 24 or 48 hours.

Some groups, however, attempt to influence elections through “issue advocacy.” Some of these communications are as they sound—legitimate efforts to influence elected officials to support or oppose legislation or other pending matters. But, other “issue advocacy” communications are actually thinly veiled efforts to convince voters to support or oppose a particular candidate. An ad that looks exactly the same as an electioneering communication is considered “issue advocacy” if it falls outside of the windows of time described above. This type of sham issue advocacy is not tracked by the FEC or any public agency. While there are some private organizations that track these issue ads, there is no free central public database.

A recent Federal Communications Commission rule will require broadcasters to make this information available online. But, the information will not be in a searchable format. And, the requirement will initially only apply to affiliates of the four major networks in the top 50 media markets; remaining stations have until July 2014 to comply. Media tracking firm Kantar CMAG estimates that the rule will cover 60 percent of the political ads in the 2012 cycle.

This reporting gap prevents us from giving a complete picture of all the outside spending by those attempting to influence the election. But, we do know that many groups that spend on such communications are 501(c)(4) nonprofits that do not have to disclose their donors. According to data from Kantar CMAG, the top four 501(c)(4) spenders on the presidential race have spent $43.3 million on advertising in the presidential race alone through July 1st, but our analysis shows that these same groups have only reported spending $418,920 collectively on all races to the FEC through June 30th. This means that these groups are currently reporting less than 1% of their total spending.

Thus the numbers reported in the above section, which do not include issue advocacy, are a vast underestimate of the true amount of secret money in this year’s election cycle and there is good reason to believe that outside spending by secret sources will eclipse that of transparent sources when the FEC begins to track many of these expenditures as electioneering communications when the general election window opens on September 7th.

Flashes of Light in the World of Dark Money

There are a few ways to estimate the actual proportion of secret money in the current election cycle. First, we can look at past practice. A study by the Center for Public Integrity and Center for Responsive Politics found that, in 2010, 501(c) groups outspent all Super PACs for the entire cycle by a ratio of three-to-two—only counting independent expenditures and electioneering communications reported to the FEC, not counting any issue advocacy.

One might think that this cycle will look quite different thanks to the unprecedented size of the candidate-specific presidential Super PACs. But, the limited available data suggests otherwise. Kantar CMAG data posted online by the Washington Post allows us a decent view of issue ad spending on the presidential campaign and gives us some evidence about the size of the gap between what’s reported to the FEC and what’s actually being spent.

Data on ad buys can tell us quite a bit about dark money in federal races beyond just the presidential campaign as well. A Washington Post analysis of Kantar CMAG data found that 91% of the spending on campaign ads through April 22, 2012 was by nonprofit organizations that do not disclose their donors.

Furthermore, although these nonprofits are not required to report their issue ad spending, some have publicly declared their intention to spend huge sums. Lee Drutman of Sunlight Foundation produced a very helpful tally showing that just a few top dark money groups have already spent more than the 2010 total for all dark money groups, and have plans to spend up to $900 million through the 2012 cycle. If these top spenders fulfill their objectives they will spend almost triple the $312 million Super PACs have raised so far this cycle.

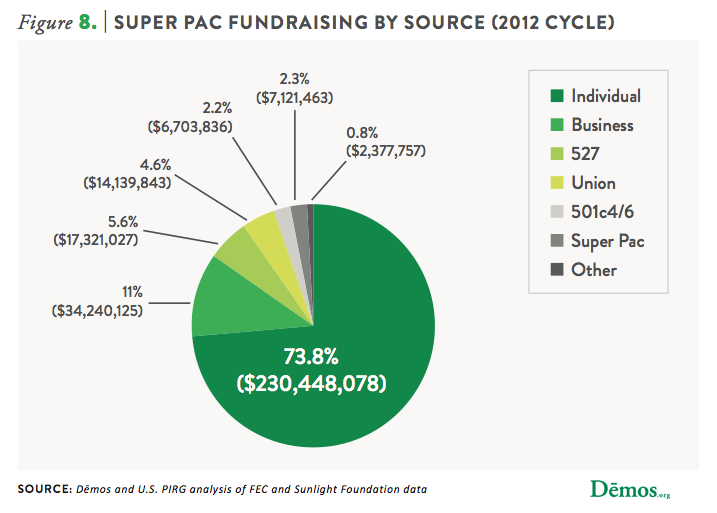

Super PACs

Our analysis of FEC data through June 30, 2012 shows that Super PACs continue to raise the majority of their funds from wealthy individuals, a significant amount of money from for-profit businesses, and a small amount of “secret” funds that cannot be traced back to an original source.

Wealthy Individuals

A small number of wealthy individuals have been dominating the financing of political campaigns since long before the courts created “independent expenditure-only committees.” But Super PACs have made a bad situation worse, and our analysis of 2012 cycle FEC data reveals the disproportionate influence of the wealthiest donors.

Individuals are responsible for the majority of Super PAC funds: 73.8 percent. The average itemized contribution from an individual to a Super PAC in the 2012 election cycle was $19,944.

Of all money Super PACs raised from individuals in the 2012 cycle, 94.1 percent came in contributions of at least $10,000—from just 1082 individuals, or 0.00035 percent of the American population. More than half (57.1 percent) of individual Super PAC money came from just 47 people giving at least $1 million. These same 47 people were responsible for 42.1% of all the money Super PACs raised for the cycle (counting contributions from both individuals and organizations).

Business Money

Allowing for-profit businesses to spend treasury funds to influence elections allows those who have generated wealth by making widgets or selling cell phones to translate this economic success directly into amplification of their political voice, and therefore power. This runs contrary to basic principles of political equality.

Yet, 515 for-profit businesses have contributed $34.2 million to Super PACs in the 2012 cycle, accounting for 11.0% of total Super PAC fundraising.

The percentage of Super PAC funds coming from for-profit businesses is down for the 2012 cycle compared with all Super PAC fundraising through the end of 2011 (when it was 17 percent). This is due in part to increased individual contributions to Super PACs and in part to businesses giving relatively less to Super PACs in the past six months.

The reduced level of business contributions is likely because Super PACs must report their donors and for-profit businesses have other avenues for political participation that do not risk negative exposure. A few accidental disclosures in recent months—for example, Aetna’s inadvertent reporting of $7 million dollars given to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and a 501(c)(4) corporation for—have given credence to the suspicion that secret contributions are the new favorite avenue for businesses to influence elections.

Secret Money

As noted above, most secret spending in this election has not flowed through Super PACs. While there was considerable initial concern that Super PACs were setting up non-profit arms in order to funnel money to themselves while hiding the identity of their donors, it turns out that non-profits have tended to spend money directly rather than sending it first to a Super PAC. Nonetheless, a small percentage of Super PAC funds cannot be feasibly traced to its original source.

Our analysis of FEC data shows that 2.8% of the funds raised by Super PACs in the 2012 cycle was “secret money.”

Seventeen percent of active Super PACs received money from untraceable sources. Four out of the 10 Super PACs that raised the most money in the 2012 cycle received money from untraceable sources.

Why Unlimited & Secret Outside Spending is Bad for Democracy

Justice Louis D. Brandeis famously said, "We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can't have both." He might have also said, “We can have democracy write the rules for capitalism, or we can let private wealth control public power—we have to choose.”

We live in a representative democracy with a capitalist economy. This means that we hold different values dear in the economic and political spheres.

Most Americans will tolerate some economic inequality, so long as it results from meritocratic competition, because we respect that other values such as efficiency and proper incentives have a role to play in structuring our economy. One’s political ideology to a certain extent determines how much inequality one is willing to sanction in the name of other values—with, all else being equal, self-identified conservatives comfortable with a wider income gap than self-identified liberals or progressives.

Political equality, on the other hand, is a core American value. Regardless of partisan or ideological affiliation, the vast majority of Americans agree that it is critical that we all come to the political table as equals. Through multiple amendments and Supreme Court decisions, the concept of political equality (“one person, one vote”) has become a core constitutional principle.

But, we cannot maintain a democracy of equal citizens in the face of significant economic inequality if we allow those who are successful (or lucky) in the economic sphere to translate wealth directly into political power. Our democratic public sphere is where we set the terms for economic competition. It is where we decide—as equals—how much inequality, redistribution, regulation, pollution we will tolerate. These choices gain legitimacy from the fact that we all had the opportunity to have our say. If economic incumbents are able to rig the rules in favor of their own success it undermines the legitimacy of the economic relations in society.

In short, democracy must write the rules for capitalism, not the other way around. And, the only way to ensure this happens is to have some mechanism for preventing wealthy individuals and institutions from translating their wealth into political power. Campaign finance rules are that mechanism. These common sense restrictions on the unfettered use of private wealth for public influence are the bulwarks or firewalls that enable us to maintain our democratic values and a capitalist economy simultaneously. When we remove these protections, we risk creating a society in which private wealth and public power are one and the same.

Non-candidate spending in federal elections is not inherently bad. But, in our current system, outside spending amplifies the voices of the wealthy and allows a tiny minority of wealthy individuals and interests to drown out the voices of the vast majority of average-earning citizens.

As noted above, many outside spending organizations do not report the source or amount of their contributions. But, what we do know demonstrates that a huge percentage of the money raised and spent by these groups is coming from a tiny number of wealthy individuals and institutions.

Wealthy Individuals

One example reported recently by Mother Jones magazine illustrates the problem clearly. Sheldon Adelson, the billionaire casino magnate, and his wife Miriam have given a combined $36.3 million to Super PACs this election cycle. That’s a lot of money—but not to them. The Adelson family has an estimated net worth of $24.9 billion, which means that $36.3 million is just 0.15% of their total wealth. That’s the equivalent of the average middle class family (with a net worth of $77,300) spending $113 on this election. Mr. Adelson has said he’s willing to spend up to $100 million to support conservative causes and candidates this cycle—the equivalent of $310 to a motivated middle class family.

"What the Supreme Court did in Citizens United is to say to these same billionaires and the corporations they control: 'You own and control the economy; you own Wall Street; you own the coal companies; you own the oil companies. Now, for a very small percentage of your wealth, we're going to give you the opportunity to own the United States government.' '' – U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders

One could view Mr. and Mrs. Adelson as just like tens of thousands of other American couples who hold clear political views and want to do their part to make a difference—so they write a few checks that add up to a relatively trivial percentage of their net worth. The average family might cut a $75 check to the NRA or Sierra Club, and then make a $40 online gift to a presidential candidate and contribute $25 at a local congressional fundraiser. They have their voices heard, but have a small chance of making a marginal difference in any given race—similar to voting.

For the Adelson family, that same “small” set of gifts ads up to $36.3 million which can fundamentally alter the course of a presidential race. The Adelsons may not care more about politics than the average family—after all, if they did why not dig a little deeper?—but they certainly have more influence.

It would take more than 321,000 American families making the same sacrifice as the Adelsons to equal their political giving. Every single 2008 voter in the United States would have to contribute 27 cents to equal the Adelson family’s giving.

The problem is not restricted to wealthy conservatives. Noted film producer (and liberal) Jeffrey Katzenberg has contributed $2.1 million to Super PACs this cycle. Forbes estimated his net worth at $1 billion in 2005. This would make his contributions this cycle just 0.21% of his total wealth—but enough to pay for a lot of airtime to support his favorite candidates.

The fact that a tiny number of very wealthy Americans have such a louder voice in our democracy is inherently unfair. But, it would not necessarily skew political outcomes and have real-world consequences if the extremely rich and the merely rich had the same policy preferences and priorities as average-earning citizens.

A growing body of academic research, however, has demonstrated what common sense tells most of us already: very wealthy people don’t work, live, or think like the rest of us. This means that when their wealth gives their views and priorities greater weight, our elected officials focus differently and actual policy outcomes are affected.

Sheldon Adelson is one example. His most prominent policy position may not be slanted by his vast wealth, but this wealth puts extra (undemocratic) heft behind that view. The Atlantic has reported that Mr. Adelson opposes a two-state solution in the Middle East and has feuded with AIPAC, the pro-Israel lobby in Washington, for conducting activities he saw as “unduly pro-Palestinian.” Contrast this with a June 2011 Pew poll in which only 21% of Americans said President Obama was favoring Palestinians too much.

But, his other major political priority seems to be directly tied to his wallet. The New York Times recently noted that

"[Mr. Adelson] rails against the president’s ‘socialist-style economy’ and redistribution of wealth, but what he really fears is Mr. Obama’s proposal to raise taxes on companies like his that make a huge amount of money overseas. Ninety percent of the earnings of his company, the Las Vegas Sands Corporation, come from hotel and casino properties in Singapore and Macau….Because of the lower tax rate in those countries (currently zero in Macau), the company now has a United States corporate tax rate of 9.8 percent, compared with the statutory rate of 35 percent. President Obama has repeatedly proposed ending the deductions and credits that allow corporations like Las Vegas Sands to shelter billions in income overseas, but has been blocked by Republicans."

Contrast this view with the 90% of small business owners (a plurality of whom identified as Republican or leaning Republican) who believe that big corporations use loopholes to avoid paying taxes that small businesses pay, according to a February 2012 poll by the American Sustainable Business Council.

Business Spending

Contrary to the Citizens United ruling, for-profit businesses should not be permitted to spend money to influence elections. There is no more direct violation of the principle of democracy writing the rules for capitalism than to allow for-profit businesses to craft those rules by influencing who writes them.

Business spending on elections also presents challenges for shareholders who may see their money spent by managers on candidates that they do not support in a way that may bear only a tangential, or even negative, relationship to the business bottom line. In fact recent studies have shown that corporate political spending has either no effect or a negative effect on profits.

Secret Spending

Unlike limits on campaign contributions and spending, support for transparency in campaigns has traditionally been strong across the political spectrum, and the Supreme Court extolled its benefits in the very decision that laid the groundwork for Super PACs. Big spending by individuals and for-profit businesses distorts our democracy by giving some a greater voice. Secret spending presents three different types of harm.

First, and most obviously, secret spending denies voters the opportunity to “follow the money” and understand the motives behind the messages that are flooding the airwaves during election season. One might be more skeptical of an ad praising a candidate’s environmental record if one knows it is sponsored by an oil company. Senator Mitch McConnell, a leading opponent of campaign finance restrictions referred to this value when he said in 1997 that “[p]ublic disclosure of campaign contributions and spending should be expedited so voters can judge for themselves what is appropriate."

The second problem with secret spending is that it denies citizens the opportunity to hold political actors accountable for their actions in the public sphere. This reduces the incentive for groups to provide accurate information to the public, and tends to coarsen our public discourse generally. A recent Annenberg Public Policy Center study found that, “from December 1, 2011 through June 1, 2012, 85% of the dollars spent on presidential ads by four top-spending third-party groups known as 501(c)(4)s were spent on ads containing at least one claim ruled deceptive by fact-checkers at FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, the Fact Checker at the Washington Post or the Associated Press.”

It also makes other forms of accountability difficult or impossible. Consumers, for example, might not want the money they spend on hamburgers or plastic deck chairs funneled into causes or candidates they oppose. Target Corporation experienced this type of healthy accountability when its customer base reacted strongly to revelations that it contributed to an organization supporting a gubernatorial candidate who opposes equal marriage rights for same-sex couples.

Support for this concept of public accountability comes from notably conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who wrote “[r]equiring people to stand up in public for their political acts fosters civic courage, without which democracy is doomed. For my part, I do not look forward to a society which campaigns anonymously…and even exercises the direct democracy of initiative and referendum hidden from public scrutiny and protected from the accountability of criticism. This does not resemble the Home of the Brave.”

The third problem with the lack of transparency in our system is that without the full picture of election spending it is more difficult to build the case for reform. As any doctor knows, the first step to heal a system is to properly diagnose the problem. This is more difficult to do without a complete picture. As Demos C. Edwin Baker Fellow Rakim H.D. Brooks has written:

"Having complete knowledge about who is bankrolling political ads would permit the American people to finally have an empirical conversation about corporate influence in, and elite domination of, our political debates. Imagine if, tomorrow, the New York Times revealed that 90 percent of all political ads were sponsored by the same 100 people. It might not change our reflections on the substance of the ads. Again, I believe we can ascertain…fact from fiction well enough now. But we might ask the more fundamental question of whether it is fair for so few to speak so frequently."

Right now, even by diligently searching FEC filings, a citizen cannot know exactly how few people or institutions are responsible for how many decibels in the public debate over the 2012 elections.

Conclusion

Outside spending is not inherently bad. But, our research shows that outside spending groups that aggregate unlimited contributions are distorting our democracy, functioning as megaphones for (sometimes unseen) millionaires and moguls.

We know that the vast majority of the funds raised by transparent organizations such as Super PACs is coming from a small number of wealthy individuals and for-profit businesses. Other groups are spending millions to influence our votes without reporting their donors. And, millions of dollars of this “dark money” is doubly-secret—not only are the donors undisclosed, but the spending itself is not reported to the public in any systemic way.

This undermines political equality and accountability, and denies voters the opportunity to properly evaluate messages targeted at them, and the ability to see the full scope of distortion. In the following section we provide recommendations for mitigating the undemocratic influence of these organizations.

Recommendations

- Amend the Constitution to clarify that the people have the right to democratically enact content-neutral limitations on campaign contributions and spending by individuals and corporations in order to promote political equality. Short of a dramatic turnover on the U.S. Supreme Court, the only complete solution to the problems presented by unlimited outside spending is to amend the U.S. Constitution to clarify that the First Amendment was never intended as a tool for use by corporations and the wealthy to dominate the political arena.

- Encourage small political contributions by providing vouchers or tax credits. Encouraging millions of average-earning Americans to make small contributions can help counterbalance the influence of the wealthy few. Several states provide refunds or tax credits for small political contributions, and the federal tax code did the same between 1971 and 1986. Past experience suggests that a well-designed program can motivate more small donors to participate. An ideal program would provide vouchers to citizens up front, eliminating disposable income as a factor in political giving.

- Match small contributions with public resources to encourage small donor participation and provide candidates with additional clean resources. Candidates who demonstrate their ability to mobilize support in their districts should receive a public grant to kick-start their campaign, and be eligible for funds to match further small donor fundraising. This would both encourage average citizens to participate in campaigns and enable candidates without access to big-money networks to run viable campaigns for federal office.

- Require disclosure of all funds spent to influence federal elections and the donors behind these funds. Congress and the FEC should expand disclosure requirements to shine light on “dark money” and give citizens the information they need to make informed decisions and hold political actors accountable. Donors whose funds are used for political spending should be disclosed above a reasonable threshold (such as the current FEC $200 threshold for itemized contributions).

- Set clear standards for political activity for 501(c) tax-exempt organizations to ensure that influencing elections is not a substantial part of their activities. The Internal Revenue Service should clearly define its “primary purpose” test so that political activity is an insubstantial portion of an exempt organization’s budget and activities.

- Protect the interests of shareholders whose funds may currently be used for political expenditures without their knowledge or approval. Congress should require for-profit corporations to obtain the approval of their shareholders before making any electoral expenditures, including contributions to other organizations that engage in political activity (such as 501(c)s and Super PACs); and require any for-profit corporation to publicly disclose any contributions to a 501(c)(4) or 501(c)(6) organization that makes an independent expenditure, funds an electioneering communication, or contributes to a Super PAC.

- Tighten rules on coordination. Current rules prohibiting coordination between Super PACs and candidates are riddled with loopholes. The Federal Election Commission should issue stronger regulations that establish legitimate separation between candidates and Super PACs. For example, the Commission could prevent candidates from raising money for Super PACs; prevent a person from starting or working for a Super PAC supporting a particular candidate if that person has been on the candidate's official or campaign staff within two years; and prevent candidates from appearing in Super PAC ads (other than through already-public footage). If the FEC refuses to act, Congress can pass these same rules through statute.

- Expand the “electioneering communications” windows to account for the length of modern campaigns. To facilitate full disclosure of election-related activity in the modern campaign era, the electioneering communications windows should be expanded to begin 120 days before the first presidential primary and January 1st of each election year for congressional elections.

- Require Super PACs to include basic information about the tax and political committee status of their institutional donors in disclosure filings. This simple adjustment would make it far easier for concerned citizens to “follow the money.”

To view the methodology of this report please download the PDF