Key Points

In the U.S., it is long-standing practice to count every individual in the country for the purposes of drawing legislative districts. However, recent federal and state efforts seek to change this practice in a way that would reduce the political power of—and the resources provided to—Black and brown people:

- Counting every person for purposes of apportionment allows lawmakers to fairly allocate resources to communities for crucial public services, and gives a voice to populations, from children to non-citizens, including undocumented immigrants, who may not be eligible to vote but nonetheless are integral to their community.

- Through a recent memorandum, the Trump administration has signaled its intent to systematically exclude undocumented adults and children from the process for determining congressional apportionments, deliberately increasing white political power and reducing representation and funding for Black and brown communities.

- In some states, lawmakers have discussed or are attempting to erase children, non-citizens, and other groups from apportionment counts.

- In Missouri, lawmakers passed a law earlier this year that has placed a proposed constitutional amendment—Amendment 3—on Missouri’s November 2020 ballot. If passed, Amendment 3 would open the door to counting only the citizen voting-age population for legislative apportionments, which would exclude 1.4 million children and 126,000 non-citizens from representation, and drastically lower representation for Black and brown communities.

- Exclusion of non-citizens and children from apportionment counts would also result in moving political power away from more diverse suburbs and cities to rural areas with predominantly white populations.

Introduction

In a representative democracy, political power starts with being counted. Ensuring that we count all members of our communities for the purposes of drawing legislative districts and allocating public resources is fundamental to a government that is responsive to everyone. This is especially true for Black, brown, and immigrant communities, who have so often been denied representation and political power in our country.

This principle is clear in our founding documents. The United States Constitution mandates that, when apportioning congressional seats or redistricting, all individuals must be counted. Throughout our history, Congress and the courts have reaffirmed that congressional seats are determined by counting all residents within a state, regardless of age, race, documented status, or eligibility to vote. From the 14th Amendment’s mandate that "the whole number of persons in each State" must be counted for congressional apportionment, to the Supreme Court’s reaffirmation that an undocumented individual living in the United States “is surely ‘a person’ in any ordinary sense of that term,” “[w]hatever his status under the immigration laws,” the law is explicit: representation shall be determined based on the total resident population. How we count individuals determines who has political representation and political power, as it is the basis on which district lines are drawn. The count also determines the distribution of federal funds for many vital government services, such as health care and nutrition assistance.

Further, every U.S. state currently uses its total population count when drawing state legislative maps. This federal and state practice recognizes that, while members of our communities may not be able to cast a ballot—be they young, a non-citizen, or someone stripped of their voting eligibility due to a felony conviction, mental incapacity, etc.—each of these individuals matters and each must be counted if we are to guarantee that communities are properly resourced and people receive necessary services.

Unfortunately, this shared principle is being threatened at the federal and state level through a group of racist, anti-immigrant measures. As a result, millions of individuals are at risk of losing representation in our democracy and face potential budget cuts that will prevent their communities from thriving.

Trump Administration and Missouri Lawmakers’ Efforts to Change Who is Counted

Today, the Trump administration is attempting to fundamentally change how apportionment is done, by ordering federal agencies to collect data on undocumented populations and share that data with states for the purpose of excluding undocumented people from political representation. This would have the impact of excluding over 10 million people from the apportionment base, diluting the political voice of Black and brown communities, and reducing funding for many communities’ public services. Several lawsuits were filed to block the Trump administration from executing this plan, and resulted in multiple rulings that the administration's plan is unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has fast-tracked the case and is set to hear it on November 30, 2020.

Simultaneously, lawmakers in Missouri are advancing a plan that could exclude both children and non-citizens from legislative apportionment by counting only the “citizen voting-age population” (CVAP) instead of the total population, which would distort political power and funding away from families and toward older, predominantly white communities. Voters in Missouri will be faced with this proposal—Amendment 3—on the November 2020 ballot. The adoption of either of these measures would be unprecedented and impact the allocation of political power and resources for at least the next decade.

Gerrymandering experts, even those sympathetic to the administration’s efforts, have acknowledged that counting exclusively the voting-eligible population would not only run counter to our current standard, it would also amplify white political power. For example, political strategist Thomas Hofeller conceded that moving from counting the total population to the citizen voting-age population would be a “radical departure from the federal... rule presently used in the United States.” Hofeller also wrote in 2015 that “a switch to the use of citizen voting age population as the redistricting population base for redistricting would be advantageous to… Non-Hispanic Whites.”

Failing to count the whole population for redistricting purposes or apportionments would be disastrous for Black and brown communities. By effectively erasing children and immigrants from apportionment numbers, communities with higher numbers of children and immigrant households would see major funding cuts from programs that are allocated based on population. This will also impact 8.2 million Americans living in “mixed status” households with members of different immigration and citizenship statuses. Below, we detail these pernicious federal and state proposals, and discuss how they threaten our ability to build a truly inclusive and representative democracy.

The Trump Administration Is Fighting to Exclude Millions of Immigrant Families from Representation

For the past 3 years, the Trump administration has advanced policies that would exclude immigrant families from the census count and thereby dilute the political power of Black and brown communities. In 2017, the Department of Commerce fought to add a citizenship question to the 2020 Census, which would have deterred millions of people from participating in the census out of fear or uncertainty, reducing representation of communities of color in Congress. Although the Supreme Court eventually ruled that the Trump administration cannot add a citizenship question to the 2020 Census, the attacks to our democracy and how we count individuals did not stop.

On July 11, 2019—in response to the Supreme Court decision— Trump issued an “Executive Order on Collecting Information about Citizenship Status in Connection with the Decennial Census.” The 2019 Executive Order explicitly asserted that states and localities may be able use this citizenship information for redistricting purposes and “could more effectively exercise this option with a more accurate and complete count of the citizen population.” The Trump administration claimed that it is necessary to count the undocumented population to evaluate immigration policy and effectively implement federal programs, and it requires various government agencies, including the Department of State, the Social Security Administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Customs and Border Patrol, and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, to provide access to records regarding citizenship status.

In July 2020, the Trump administration issued a “Memorandum on Excluding Illegal Aliens from the Apportionment Base Following the 2020 Census,” in an attempt to revitalize a voter suppression tactic contemplated in the 1980s but rejected by previous administrations on the grounds of unconstitutionality. The explicit purpose of the memorandum is to exclude undocumented immigrants from Congressional apportionment. In the memorandum, the administration claimed that the Constitution does not specifically define which persons must be included in apportionment. While the memorandum conceded that the term “persons in each State” has been interpreted to mean that the “inhabitants” of each state should be included, it argued that determining which persons should be considered “inhabitants” for the purpose of apportionment requires an “exercise of judgment” and that the executive branch can exercise this authority by, for instance, “exclud[ing] from the apportionment base [people] who are not in a lawful immigration status.” Advocates and elected officials have pushed back against what the Trump administration considered a sound exercise of judgment, and multiple lawsuits have been filed to prevent the administration from executing this memo. While multiple courts have found the memorandum to be unconstitutional, the U.S. Supreme Court is set to consider the issue later this year.

The impact of the July memorandum would be the exclusion of over 10 million people from apportionment who are predominantly from communities of color. According to a study conducted by Pew Research Center in 2017, about 4.95 million of the 10.5 million undocumented population were from Mexico, 1.9 million from Central America, and 1.45 million from Asia.

This brazen attack on immigrant communities affects all of us. About two-thirds of undocumented immigrants have been in the U.S. for 10 years or longer, indicating that they have strong ties to their communities and families in the United States. Undocumented immigrants are an integral part of American society, and our communities and economy could not thrive without their contributions. More than 16.7 million people nationwide have at least one undocumented family member living with them, 8.2 million of whom were born in the United States or are naturalized citizens. This includes 5.9 million citizen children who will potentially be at risk of losing vital public services if their undocumented family members are not counted. Further, this memorandum would hurt the many Americans who reside near their undocumented family members and friends by diluting their representation and access to state and federal services.

The Trump administration’s recent effort to cut short the census count only adds to the list of measures taken to manipulate the census and suppress the political power of Black and brown voters. After appealing a lower court decision that allowed the 2020 census—which has been conducted during an unprecedented global pandemic—to continue until October 31, the Trump administration secured a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court on October 13, 2020 that the last day to submit census responses would be October 15—a mere 2 days later. As Justice Sotomayor noted in her dissent, the hundreds of thousands of people who will be left uncounted “is likely much higher among marginalized populations and hard-to-count areas,” including on tribal lands.

From art to medicine, and from caregiving to agriculture, immigrants, including undocumented immigrants have made countless contributions to the United States, and proper representation is necessary to ensure that these communities and their neighbors can access the important public services that help them thrive, such as health care and stable housing that their tax dollars fund. A plan that would benefit non-Hispanic white populations and clearly amplify their political power is not rational in a democratic society, and it can well be considered invidiously discriminatory.

Missouri and Other States Are Working to Exclude Millions from Representation

It is not only the federal government that has deployed tactics aimed at stripping Black and brown communities of political power—states are following suit. For example, lawmakers in, Arizona, Missouri, Nebraska, and Texas have indicated that they would consider using “citizenship data for redistricting purposes if it became available.”

Amendment 3 in Missouri

In May 2020, the Missouri State Senate passed SJR 38, acting on its earlier threat to move away from total population count for purposes of reapportionment. In passing SJR 38, the Missouri legislature has put forward a ballot initiative (Amendment 3) that voters will be asked to pass or reject in November 2020. Among other things, Amendment 3 seeks to end the state's practice of counting the total population for purposes of congressional apportionment by changing the current language, which establishes districts “on the basis of total population,” to establish districts that are “drawn on the basis of one person, one vote.” If adopted, Amendment 3 could allow lawmakers to use CVAP data to exclude children and non-citizens. It would be a radical departure from how the Missouri Constitution has required legislative maps to be drawn for 145 years.

Senator Dan Hegeman (R-D12), SJR 38’s sponsor, stated that “the point of” this effort is “to forgo the use of total population to draw districts in order to leave out non-citizens.” Election law experts have noted that applying this standard could result in the exclusion of both children and non-citizens from the calculus when districts are drawn. The damage would be long-lasting, and fundamentally unfair. Because the apportionment standard will dictate district lines for a decade, Missouri‘s exclusion of youth under the age of 18 and non-citizens will mean that those who become qualified to vote during that decade, either by naturalizing or by reaching the age of 18, would be rendered invisible by the count.

Amendment 3’s Disparate Impact on Black and Brown Communities

This backdoor method of voter suppression will have serious and disproportionate consequences on Black and brown Missourians. Exclusion of non-citizens and children from apportionment counts would result in moving “political power away from the suburbs” and cities to “older, rural areas,” with predominantly white populations. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey, this plan would exclude about a quarter of Missouri’s population from the count: it would exclude about 126,200 of the non-citizens living in Missouri, or about 2.2 percent of the state’s total population, and would also exclude 1.4 million children (or individuals under the age of 18), who comprise about 22.5 percent of Missouri’s total population. If Amendment 3 is instated, over 90 percent of the people excluded from Missouri’s apportionment base under CVAP would be children. This equates to a loss of vital funding for public services such as education, health care, and food security for these children.

Removing children from Missouri’s population count would directly dilute political power of Black and brown communities, as children comprise a higher percentage of the population of Missouri’s Black and Latinx communities, which skew younger than white communities: citizen children make up 21 percent of the population in white communities, 26.7 percent of the population in Black communities, and 37 percent of the population in Latinx communities.

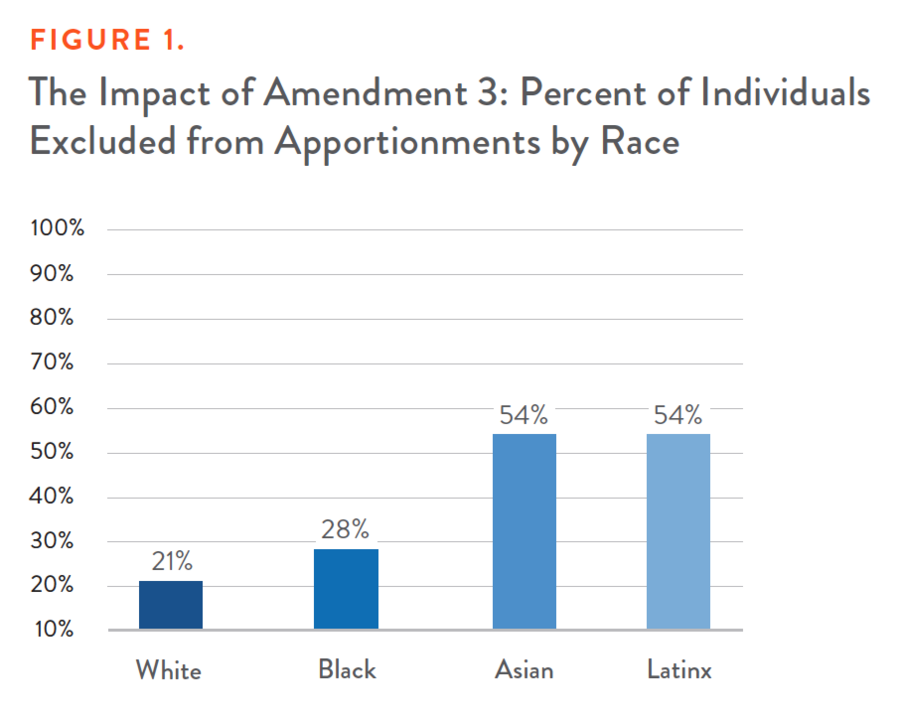

The reduced representation Black and brown Missourians would experience if Amendment 3 is adopted is even more stark when noncitizens are also excluded from the population count: if instated, 21 percent of Missouri’s white population would be excluded from the count, while 28, 54, and 54 percent, respectively, of Missouri’s Black, Asian, and Latinx populations would be excluded from the apportionment count.

Amendment 3’s Impact on Resources Provided to and the Political Power of Black and Brown Communities

Families need to be counted in order to elect representatives who are responsive to their needs, and who promise to fight for their communities and ensure all their constituents are cared for. A move to CVAP-based apportionment in Missouri would limit the ability of Black and brown communities to do just that. First, Black Missourians would lose representation off the bat, since “two out of the four districts that elected members of Missouri’s Legislative Black Caucus” would lose representation under CVAP-based apportionment. Second, counties provide services to all people residing in their county, including health care, human services, parks and recreation, public works, environmental health, judicial services, and public safety. Undercounting and underrepresenting the number of people living within a county or jurisdiction may impact local budgets, by denying jurisdictions the proportion of funding needed to provide their residents with essential services.

The adoption of CVAP-based apportionment in Missouri or other states would have devastating effects on Black and brown households and communities and would normalize a new method of voter suppression. At present, every state conducts apportionment using total population; however, voting rights advocates have warned that if Amendment 3 passes and is allowed to be implemented, other states are also likely to move forward on using CVAP-based apportionment.

We Must Build the Political Power of Black, Brown, and Immigrant Communities

These measures are a step backward in building an inclusive democracy. Apportionment schemes designed to exclude non-citizens, children, or other members of our society, whether adopted at the state level or the federal level, would result in reduced representation for Black and brown people and likely also for mixed-status families. Along with this shift in political power, such measures would impact the ability of Black and brown communities to elect their representatives of choice and receive the necessary, proportional share of tax-funded resources needed to provide critical services, such as health care and better infrastructure. These communities’ voices, experiences, and leadership should be centered, not rendered silent and invisible.

By building political power and representation among groups that have been so often locked out of our democracy, we may be able to make progress on critical issues from reversing public funding cuts, to addressing housing insecurity, to tackling systemic abuse and injustice in our police and criminal legal systems. As elected officials continue to propose new ways to disenfranchise and suppress Black and brown voters, it is essential for communities to stand up and urge lawmakers to count them. This means voting for policies that create a more representative democracy, pressuring the Supreme Court to preserve the principle that all individuals should be counted in apportionments, while also continuing to fight for long-term structural change that will build a more representative democracy.