Introduction

In a well-functioning democracy, everyone has an equal say in how their government is run and all people have the ability to impact policies that affect their daily lives. Yet, too often the pervasive influence of big money in our politics determines whose voices are heard in the halls of power. Following a series of Supreme Court decisions that opened up elections to more big money, large donors have a more outsized say than ever before. Instead of the democratic ideal of a government of, by, and for the people, an unrepresentative donor class that is whiter, higher-income, older, and more male than the U.S. population as a whole has the loudest say in policy decisions.

Cities like Albuquerque have not escaped this national reality. A small pool of donors contributing at least $1,000 each provided the majority of campaign funds in the last city election. This donor pool does not match the city’s diversity when it comes to race, income, gender, or age. Although people of color are the majority in Albuquerque, donors to city candidates are overwhelmingly white. Such stark underrepresentation distorts who has influence in city hall and diminishes the concerns and needs of a majority of constituents.

The soaring costs of campaigns force candidates to raise money from big donors who don’t look like, and generally hold different views from, the average constituent. Candidates at every level are obliged to spend significant amounts of time fundraising from and hearing the policy preferences of big donors. This results in an imbalance in political power that is reinforced by inequalities in our economy: Communities of color, low-income families, women, and young people are all less likely to have the economic resources that might gain them influence in the political conversation, and are thus absent or underrepresented among the big donor class. A growing body of evidence shows that politicians pay more attention to the policy preferences of the elite donor class, while other concerns facing our communities are sidelined.

In addition to shaping who candidates talk to, the big money chase plays a large role in determining who can run for office in the first place. Candidates need money to increase their name recognition and get their message out. Regardless of their qualifications, candidates from low-income and working-class communities, candidates of color, women of all races, and young people are frequently deprived of an equal shot at running for and winning elected office because they lack access to big donors.

It’s no wonder that trust in government is at historic lows, and campaign finance reform has become a priority issue for many national politicians. Candidates at every level of government need an alternative to our big-money system that will allow them to successfully compete while relying on financial support from everyday constituents. In dozens of states and localities across the country, small-donor public financing has proven to be the best solution both to limit big money in politics and to give regular people a louder voice.

In Albuquerque, a grassroots effort to change the way campaigns for city elected offices are financed promises to reduce the role of big money in politics. The proposal—known as Democracy Dollars—would give more residents the opportunity to participate in funding campaigns and make their voices heard. It is not the city’s first grassroots effort to curb the influence of big money in city elections. In 2005, in response to a public initiative, Albuquerque created a public financing system to enable candidates to run for office without relying on big donors. For a time, the program was successful. Then, in 2011 opponents of campaign finance reform won a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in an Arizona case that invalidated a portion of Albuquerque’s law that provided matching funds for publicly financed candidates, making it harder for them to compete with privately financed candidates. In 2018, in an effort to enhance the city’s existing program, a community-led campaign succeeded in collecting approximately 28,000 petition signatures from Albuquerque voters to put a proposal on the ballot to modernize the program and help candidates keep up with the rising costs of campaigns.

On November 5, 2019, voters will have the opportunity to vote on the creation of Democracy Dollars to give Albuquerque residents $25 coupons they can donate to the candidates of their choosing, if those candidates qualify for public financing. By making more residents potential donors, Democracy Dollars would give candidates the freedom to run without big money and a reason to get out and talk to all constituents. The program would democratize the city’s elections and policy making process by giving more residents an outlet to have their voices heard, and making candidates more accountable to everyday people.

Demos analyzed data on contributions from individual donors to city council and mayoral candidates in the 2017 election. In this report, we expose the role of big money in Albuquerque politics, examine the demographics of the donor class in relation to the city’s residents, and make the case for Democracy Dollars as a solution to give more power to the people. We find that:

- Big donors play an outsized role in Albuquerque’s elections. While only 11 percent of contributions were amounts of $1,000 or more, these contributions account for the majority—65 percent—of all funds raised by general election candidates from individual donors.

- Albuquerque donors do not match the city’s racial, age, income, or gender diversity. The donor class is whiter, older, higher-income, and more male than the city’s residents as a whole.

- Donations from outside of the state of New Mexico play a notable role in Albuquerque’s elections.

- The experience of dozens of small-donor public financing programs across the country—including Seattle’s pioneering Democracy Vouchers program—indicate that Democracy Dollars would create a more representative and responsive democracy in Albuquerque.

About the Data

Our analysis is based on data on contributions from individuals to Albuquerque mayoral and city council candidates during the 2017 general elections, publicly available via the City of Albuquerque. The data analyzed is limited to the 2017 calendar year since, according to Albuquerque campaign finance data, no individual contributions to 2017 general election candidates were made in the 2016 calendar year. The analysis focuses on individual contributions made directly to campaigns and does not cover the full range of funds potentially available to candidates (i.e. those from parties, PACs, interest groups, or direct expenditures on behalf of candidates). Contribution refunds are not included in this analysis. The contributions covered in this analysis include cash/check/credit/direct transfers, in-kind contributions, and loans. Although loans must be repaid, they are included in contributions because they are of great value to candidates. Demographic data is derived from modeling methodology developed in conjunction with political scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Albuquerque’s Decades-Long Effort to Limit the Role of Big Money in Local Politics

Tackling big money has been a decades-long issue in Albuquerque politics, culminating in the overwhelming 2005 approval of a public financing program that gave candidates an opportunity to campaign for office without relying on big donors. While the effectiveness of the program was limited after a 2011 U.S. Supreme Court decision, it is clear that Albuquerque’s voters have a long-standing interest in reining in the influence of big donors. To better understand how the public financing program in Albuquerque became a reality, it is important to first look at the social and political factors that played a role in the approval of the program in 2005.

In New Mexico, as in other places, “pay to play” politics have pervaded state and local political practices for a long time and served as a catalyst for popular support for campaign and election reform. Concerns about the disproportionate financial influence of corporate actors, and outright corruption of elected officials, led voters to demand action on the issue. One illustrative case of pay to play politics involved New Mexico State Investment Officer Phillip Troutman and Deputy State Treasurer Ken Johnson, who were both convicted of conspiracy to commit extortion in 1984. According to the sworn testimony during trial, Troutman and Johnson were requesting money from New York bank executives in exchange for their bank receiving business from the state. Johnson is quoted as having said, “You have to pay to play,” and “This is how business is done.”

This and many other cases that followed fueled among the public a sense of dissatisfaction and distrust in the political system, and opened an opportunity to propose, pass, and eventually enact public financing for some offices and in certain elections.

New Mexico’s Trailblazing Public Financing Programs

New Mexico’s first statewide public financing program was enacted in 2003, after Gov. Bill Richardson signed legislation that created a campaign fund for candidates for the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission (PRC). Supporters of this effort praised it as a means to restore “public confidence in the political system.” Democratic Senate President Pro Tem Richard Romero said the creation of public financing was a way to lessen the influence of money in elections and politics because “those contributions have a bearing on [politics], whether we like it or not.”

The voluntary program gives PRC candidates the chance to run for office free of big-money donors and to instead spend their time seeking small contributions. To qualify, candidates are required to cap their campaign spending, reject private contributions for their campaigns, and gather $5 donations from a minimum number of registered voters in the district they wish to represent to prove they are a serious candidate. If they raise the qualifying contributions, candidates would be granted public financing based on past PRC campaign costs. However, limited funding for PRC public financing has made it difficult for candidates to compete with privately funded and industry backed candidates.

A few months after the approval of public financing for PRC elections, Max Bartlett, Executive Director of Re-Visioning New Mexico, wrote an opinion piece for the Albuquerque Journal in which he encapsulated the transformative power of public financing, stating, “Folks from average and low levels of income should have the right to democracy, too. They have a right to have their needs addressed, their concerns raised and their voices heard.”

In 2005, a second program was introduced before the New Mexico legislature to provide public financing for statewide judicial elections. This proposal garnered much support, including an endorsement from the Albuquerque Journal in their March 19, 2005 editorial titled “Judicial Campaign Reform Deserves a Try.” In the editorial, the paper made the case that public financing will restore public confidence in government by ensuring judges’ decisions are made “on the basis of the law—not politics, not connections.” While the measure was successful on the House side that year, the bill stalled for a time until it was passed into law in 2007.

Soon after, in 2008, Santa Fe voters overwhelmingly voted in favor of a proposal to “provide for meaningful public financing of campaigns for all municipal elected officials.” (The city had first established a partial public financing program in 1987.) In 2018, the city council affirmed yet another proposal to provide more public funds for candidates.

New Mexico voters and their elected leaders again and again have pioneered public financing proposals aimed at reducing the influence of big money in politics and giving everyday New Mexicans a bigger voice in politics—and Albuquerque once again has an opportunity to continue this tradition.

Albuquerque Seized the Public Financing Opportunity

In Albuquerque in 2005 City Councilor Eric Griego introduced a bill that would enable voters to approve a public financing program for city elections. Griego’s proposal called for the city to allocate one-tenth of 1 percent from the city’s general operating budget to create an “ethical elections” fund as part of his proposed Open and Ethical Elections Code. Candidates who voluntarily entered the new program would need to gather $5 donations from 1 percent of the registered voters in their respective district to qualify for public financing. The money they raised would also go into the Open and Ethical Elections Fund. After qualifying for the program, participating candidates for city council and mayor would receive $1 per registered voter in their district or the city, respectively, to assist in funding their campaigns. The Albuquerque City Council voted 5 to 2 in July of 2005 to allow voters to decide the fate of the public financing program with a referendum on October 4, 2005.

In September, a month before the election, another political scandal helped solidify the need for election reform in New Mexico. This time it was a case involving 2 state treasurers charged with taking what amounted to $700,000 in kickbacks during their time in office. News of yet another corruption case struck a chord with Albuquerque voters. A poll by Research and Polling Inc. published in October, 2005 showed the public financing measure gained 12 percentage points in approval compared to the initial poll a month prior. Brian Sanderoff, director of Research and Polling Inc., attributed some of the increase to the recent treasurer’s office scandal.

On October 4, 2005, Albuquerque voters cast their ballots, and an overwhelming 69 percent approved the public financing proposal, sending a clear message to the rest of the nation that the city “was a vanguard for election reform.”

Albuquerque joined a growing list of cities to approve a public financing program for local elections, including Santa Fe, NM in 1987; Tucson, AZ in 1987; New York City, NY in 1988; Los Angeles, CA in 1990; Long Beach, CA in 1994; Oakland, CA in 1999; Boulder, CO in 2000; and San Francisco, CA in 2000.

Albuquerque’s Experience with Public Financing

In the years that followed the approval of the 2005 Open and Ethical Elections Code, Albuquerque “was seen as a real bright spot” in terms of campaign finance reform. Several reports featured the effort, making the city a case study for implementation of a newly passed election fund.

A 2011 report by the Center for Governmental Studies noted, “The City of Albuquerque should be proud of the successes of its Open and Ethical Elections Program (OEE).” The main reason, as detailed in the report, was that since implementation of the program in 2007, 8 out of 10 elected officials in the city had won their seats using public financing for their election bids. The report also highlights the fact that public financing had “reduced the appearance of undue influence by large campaign donors.”

The same report found that Albuquerque had achieved many of the original goals set forth in the passing of the OEE program, including:

- Dramatically reducing campaign expenditures in municipal races.

- Ensuring that electoral campaigns focused on issues, rather than media campaigns fueled by special interests.

- Encouraging more municipal candidates to use public financing.

- Encouraging participation of newcomers to run in municipal elections.

Yet, participation in the public financing program has dwindled in recent years, as the rising costs of campaigns outpaced program amounts and limits for participating candidates. This is in large part due to a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court that invalidated a portion of a similar program in neighboring Arizona, which gave candidates additional funds when they faced competition from well-funded, privately financed opponents. The ruling was one of a series of cases, including the unpopular Citizens United case, in which the Supreme Court sided with pro-business interests and campaign finance reform opponents to weaken our campaign finance laws.

In 2009, the first year that public financing was available for Albuquerque city candidates, all 3 mayoral candidates on the ballot participated in the program, while 5 out of 8 city council candidates qualified for public financing. In comparison, in 2013, just 1 out of 3 mayoral candidates on the ballot participated in the public financing program, and just 1 out of 8 in 2017. Of the 14 city council candidates in 2017, only 6 qualified for public funds.

Albuquerque voters have shown overwhelming support for solutions to reduce the power of big money in politics and give candidates an opportunity to raise funds from regular constituents. In order for the program to achieve the aims for which voters passed it, the program must keep up with the rising costs of campaigns so that it is a viable option for candidates to use.

As the following sections reveal, Albuquerque’s current campaign finance system could do more to limit the role of big money in local elections and ensure candidates rely on donors who are reflective of the people they hope to represent.

Big Money’s Outsized Influence in Albuquerque Elections

Like most of the country, Albuquerque has a big-money-in-politics problem. Americans overwhelmingly agree that large donors have too much influence over our elections and that new laws are needed to address the problem. Albuquerque was one of the earlier places to respond to this concern with the creation of its existing public financing program. However, following Supreme Court interference that weakened the program, big donors continue to have an outsized role in city elections. A review of donations from individuals to mayoral and city council races in 2017 shows that large donors greatly outspent small donors: Despite the fact that the majority of donations consisted of donors giving $250 or less, that money was swamped by the minority of donations of $1,000 or more.

Big Donors Overwhelm Small Donor Giving

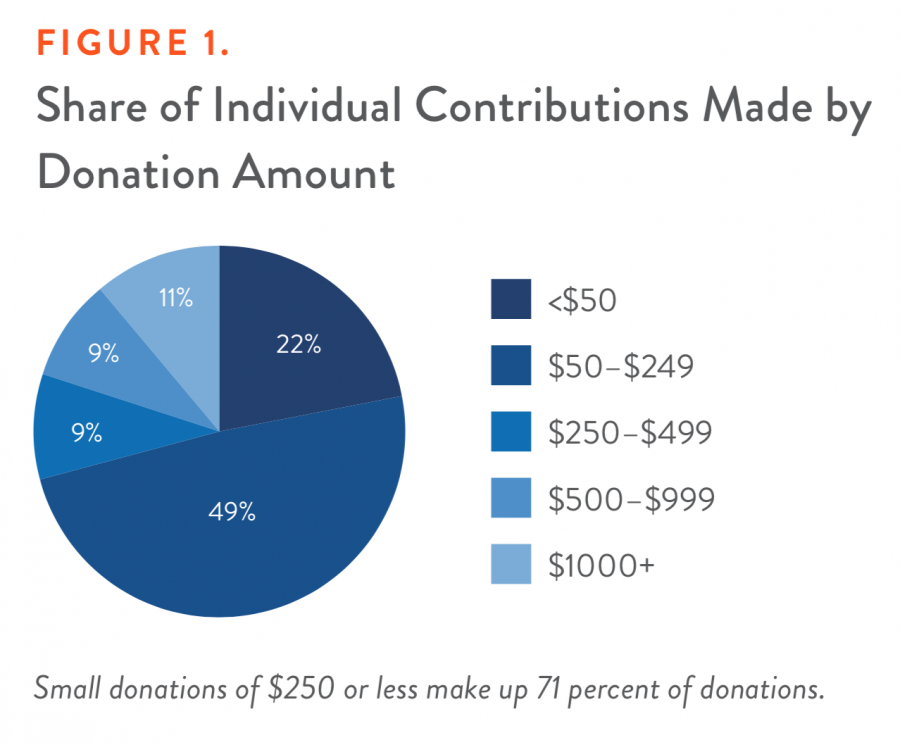

A relatively few large donors drowned out the combined influence of the city’s small donors. While only 11 percent of contributions were amounts of $1,000 or more (see Figure 1), these contributions account for the majority—65 percent—of all funds raised by general election candidates from individual contributions (see Figure 2). In contrast, while nearly one-quarter of all individual contributions were less than $50, these small donations account for only about 1 percent of total funds raised by general election candidates.

Many small donors are contributing to candidates in Albuquerque, yet collectively these donations aren’t providing enough to compete with the power of big donors. As Figure 1 shows, fully 71 percent of donations from individuals were of amounts of less than $250, while only 20 percent were of amounts of more than $500. The great number of small contributions led to a low median contribution of just $100, yet large donors pulled the average donation up to $370. Despite the presence of many small donors, candidates are still relying heavily on their largest donors to provide the majority of their campaign funds.

Spotlight on 2017 Mayoral Candidates

While as a whole the 2017 candidates for city council and mayor relied most heavily on large donors to fund their campaigns, a deeper look at each candidate’s fundraising reveals that small-donor public financing has the potential to increase the voices of modest donors in elections, when the program offers more candidates a competitive option to fund their campaigns.

Among mayoral candidates on the 2017 ballot, winner Tim Keller was the only candidate to participate in the existing public financing program. Compared to his opponents, he relied heavily on small donors to fund his campaign, as Figure 3 illustrates. Among the top 5 fundraisers, 4 out of 5 received 65 percent or more of their total money from donations of $1,000 or more. Keller was the only one among them to receive the majority of his money from donors contributing $250 or less.

As Figure 4 shows below, Brian Colon raised over $700,000 from individual donors. Dan Lewis, who along with Keller was a top vote-getter and faced Keller in a run-off election, raised over $500,000. Wayne Johnson raised nearly $300,000. Keller raised just about $76,000 from individual donors as seed money and in-kind donations, allowed but limited in the public financing program, and he collected thousands of signatures and $5 contributions from registered voters that were turned into the City Clerk’s office so he could qualify for approximately $468,000 in public funds (for the regular and run-off elections, combined). Michelle Garcia Holmes rounded out the list of top 5 fundraisers by raising $63,000. There were 3 other candidates for mayor in the race, although they raised significantly less than their competitors. Augustus Pedrotty raised approximately $17,500 from individual donors. Susan Wheeler-Deichsel raised just over $7,000. Ricardo Chaves, who dropped out of the race the week before the election but appeared on the ballot, was not recorded as having any contributions from individuals.

Most candidates did not use the public financing system, likely because they believed they would be able to raise more from private donations. Indeed, privately financed candidates’ large fundraising totals suggests they had reason to believe they would have a competitive edge if not participating in the program. Keller admits that he would not have been able to run a successful campaign using public financing if he did not have the advantage of name recognition at the start of his campaign, due to the time he served as a New Mexico state senator and then as New Mexico’s state auditor.

Within a campaign finance system where privately financed candidates can easily and vastly outspend publicly financed mayoral candidates, in particular, Keller's ability to compete got a boost from the spending of measure finance committees, entities in Albuquerque similar to political action committees that can spend on behalf of candidates but cannot coordinate directly with candidates. This analysis is focused on the role of direct fundraising by candidates, since that is the best indicator of how candidates spend their time on the campaign trail while fundraising. The current post-Citizens United reality is that non-candidate spending can play a role in elections, particularly in competitive races. A strong public financing program, in which participating candidates can compete with funds directly managed by their campaign, including with the support of small donors, should reduce the incentive for and influence of non-candidate spending such as measured finance committees.

The fact that none of the 2017 mayoral candidates participated in the public financing program, apart from Keller, who benefited from higher name recognition and outside spending on his behalf, is a strong indication that the program is not currently considered a viable option for most mayoral candidates. Updating the city’s public financing program would ensure that candidates who use it do not have to run on shoestring budgets while relying on other advantages to get them across the finish line. Instead, all candidates could run competitive campaigns while spending more time seeking out small donations from constituents.

Moving Towards Greater Reliance on Small Donors

Every Albuquerque resident deserves to have a say in how their city is run, regardless of the size of their wallet. Instead, year after year, those with the most money to give play a disproportionate role in Albuquerque elections, enjoying greater power to influence elected officials and policy outcomes in the city. Albuquerque’s current campaign finance system still allows big donors to have an outsized say in elections, drowning out the voices of everyday constituents who can’t afford to write large checks. Updates to Albuquerque’s current campaign finance system are needed to limit the role of big donors and give everyday constituents a bigger say in local matters.

To better understand who is funding Albuquerque elections, the following section takes a look at the makeup of the donor class itself, exploring the demographics of the people who fuel Albuquerque’s elections.

Albuquerque Donors Do Not Match the City's Diversity

In a democracy, everyone should have a voice at the table regardless of their race, gender, age, income, or background. The reality of political campaigns today is that candidates need money to get their message out, and therefore spend a significant portion of their time with potential donors. Under our current campaign finance system, those donors often do not reflect the diversity of the constituents elected leaders represent. A look at the individuals contributing to Albuquerque’s mayoral and city council campaigns in 2017 shows that donors do not reflect the city’s diverse population. The donor class is whiter, older, higher-income, and more male than the city’s residents.

Race

The donor class in Albuquerque is much whiter than the city, as Figure 5 shows. While 41 percent of Albuquerque residents are white and 48 percent are Hispanic, the donor pool in Albuquerque is 70 percent white and only 23 percent Hispanic. Native Americans make up 4 percent of Albuquerque residents but only .04 percent of donors to city elections. Black people constitute 3 percent of the population but just 1 percent of donors. Asian Americans make up 3 percent of Albuquerque residents, but less than 1 percent of donors. When most of the money funding city elections comes from white donors, candidates spend a disproportionate amount of their time talking—and listening—to white constituents, and as a result, their policy making is more likely to tilt in favor of the preferences of white residents. Meanwhile, the concerns and preferences of constituents of color are minimized or ignored.

Age

The donor class is much older than the city’s residents (see Figure 6). While residents under 35 make up nearly half (48 percent) of the population, they make up less than 10 percent of donors. Meanwhile, donors over the age of 50 constitute a full 74 percent of the donor class despite being only about a third of the population. As a result, on issues for which opinions differ across generational divides, the concerns of the mostly older donor class are more likely to be heard, while politicians may be unresponsive to concerns facing younger voters. Of course, people generally have more disposable income available for things like campaign contributions later in life, so we would expect fewer young residents to be campaign donors than older ones. However, young people’s lives are just as governed by local politics and policy as everyone else—arguably more, since they will live with the consequences for longer—and the current campaign finance system drowns out their important voices.

Income

The donor class in Albuquerque is dominated by people with large household incomes, as Figure 7 shows. Half of all families in Albuquerque make $48,000 or less per year, yet those households make up only about a quarter of donors. Forty-one percent of donations came from households making more than $100,000, while only 1 in 5 households make that much, which is more than double what the average Albuquerque household makes. And only about 400 donors, who each gave $1,000 or more, contributed the vast majority of all dollars collected by candidates from individuals. The policy preferences of high-income donors differ from everyone else, yet as we’ve seen at the federal level, when those donors dominate election giving, their preferences dictate policy outcomes. In order to ensure government is working for low- and middle-income families, everyday Albuquerqueans, regardless of how much money they make, must fuel our elections, not just the most well-connected and well-resourced among the city’s residents.

Gender

While women make up the majority of Albuquerque residents—51 percent of the population—the donor class is dominated by men. Fifty-nine percent of donors are men, while only 41 percent are women, as Figure 8 illustrates. Women have different policy preferences than men. An AAPI Civic Engagement Fund and Groundswell Fund analysis of poll data found, “Women prioritize health care, gun violence, and race relations/racism, whereas men prioritize the economy/jobs, border security, and government spending and taxes.” When women are underrepresented in our current campaign finance system, their policy preferences are sidelined.

Prioritizing small donors has the potential to give women a bigger voice. As Figure 9 shows, among Albuquerque donors, women are better represented at smaller donor levels.

Out-of-State Donors

Donations from outside of the state of New Mexico play a notable role in Albuquerque’s elections. Out-of-state donors contributed nearly $100,000 to general election candidates—over 5 percent of the total funds contributed directly to candidates from individual donors. As Figure 10 illustrates, some of the largest shares of contributions came from Texas (nearly $23,000), Washington, DC (over $13,000), and California (over $11,000). The people fueling our elections should be those who live in our community and are impacted every day by local leaders’ policy decisions.

When candidates run as publicly financed candidates, there is less room for out-of-state donors to play a role in the candidates’ fundraising. Candidates who participate in Albuquerque’s current public financing system can raise money from out-of-state donors only as part of the seed money to fund their campaigns before they qualify to receive public funds. Seed money makes up no more than 10 percent of a publicly financed candidate’s total campaign funding; the rest must come from public funds. Instead of wooing distant donors, public financing candidates must spend time raising qualifying contributions from residents in their community, increasing the amount of time spent fundraising from constituents. Strengthening Albuquerque’s public financing program will open the door for more candidates to run competitive campaigns while spending their time with the people they intend to represent—the way democracy should work.

Albuquerque’s donors—who are more likely than non-donors to have their voices heard in politics—are whiter, older, higher-income, and more male than the general population. Many donors are not even constituents and do not reside in New Mexico. As a result, people of color, young people, middle- and working-class residents, and women are underrepresented in the city’s politics and policies. When people from a particular background are systematically marginalized, their needs and interests are less likely to be responded to by the elected leaders representing them. Policy outcomes skew in favor of the well-connected, and some of the biggest problems facing communities go unaddressed. As a result, public policies on everything from housing, education, and health care, to criminal justice are out of step with the needs of constituents, and everyone pays the price. Our elections are fairer—and our democracy works better—when politicians listen to the entire public they represent instead of only a few, unrepresentative big donors.

Democracy Dollars Can Make Every Voice Matter in Albuquerque’s Elections

Small-donor public financing is the best solution available to reverse the distorting effects of big money in our democracy and give everyday people a greater say in politics. Dozens of small-donor public financing programs are working in states and localities across the country to give candidates the freedom to run competitive campaigns funded by regular constituents, rather than soliciting large checks from an unrepresentative donor class. By shifting the fundraising focus to constituents, small-donor public financing ensures that those traditionally marginalized by big-money campaigns are equal participants whose voices are valued in the political process.

How Democracy Dollars Works

On November 5, 2019—14 years after 69 percent of Albuquerqueans voted to establish and fund public financing for elections—the city’s voters will decide whether to adopt a Democracy Dollars program. The program would utilize existing public financing funds to modernize a critical investment in a local democracy that works for everyone: one in which donors are more diverse, elections are more inclusive and accessible, and city government is more responsive to all people.

Democracy Dollars in the form of $25 coupons would increase the engagement of Albuquerque residents with candidates in local elections in a new, exciting way.

Candidates who wish to accept Democracy Dollars must qualify by collecting a set number of $5 contributions and signatures to demonstrate community support. At no extra cost to voters, the program would supplement and strengthen the city’s existing public financing program, to support candidates who forego large donations and spend their time collecting small donations and signatures from residents in order to qualify for the public funds.

The addition of Democracy Dollars to Albuquerque’s public financing program would give candidates the ability to run more competitive campaigns while backed by members of their communities and, once in office, to focus on the needs of everyday people.

Small Donors Better Reflect Constituents

Big donors are overwhelmingly white, high-income, and male, with policy views that differ greatly from those of the general public. Yet this small group of elite donors has enormous say over policy making in the United States. A study by researchers from Princeton University and Northwestern University found that over a two-decade period, the opinions of economic elites had a “substantial” impact on federal government policy decisions, while “average citizens have little or no independent influence.”

Small donors better reflect the demographics of our communities. They are also more likely to hold similar policy views to those who cannot afford or have never been asked to give, and who are therefore marginalized in our current campaign finance system. A system that prioritizes small donors ensures that the interests of all constituents regardless of race, gender, age, or income, are taken into account by policy makers.

Across the country, public financing programs aimed at increasing reliance on small donors have been proven to diversify the donor pools candidates rely upon. An analysis of New York City’s public financing program, one of the country’s longest-standing programs, found that small donations to city council candidates “came from a much broader array of city neighborhoods,” including along lines of race and income, than donations to state assembly candidates without a public financing program to participate in.

In Seattle, the country’s first-ever Democracy Vouchers program—which, like Democracy Dollars, gives residents coupons to contribute to candidates of their choice—has increased donor participation in elections while diversifying the donor pool. Following implementation of the program for the 2017 election, the percentage of residents participating in elections as donors tripled, rising to historic levels. During the first election, 88 percent of residents who donated their Democracy Vouchers to candidates were new or lapsed donors who had not given to candidates between 2011-2015. The people using their $25 coupons diversified the donor class, making it more representative of the city’s residents. Democracy Voucher users, when compared to cash donors, “better reflected Seattle’s population including young people, women, people of color, and less affluent residents,” according to an analysis by the Win/Win Network and Every Voice Center.

The addition of Democracy Dollars to Albuquerque’s public financing system also has the potential to increase reliance on local constituents to fund campaigns and reduce the need for out-of-state donors.

Free Candidates from the Big-Money Chase

Candidates who participate in the city’s public financing program are more likely to get the majority of their funds from small donors. Across the country, such candidates spend less time fundraising from wealthy donors, and more time with constituents. Small-donor public financing is the best way to encourage candidates to listen to constituents, helping to ensure that traditionally marginalized constituencies have their voices heard in the political process.

Santa Fe City Councilor Joseph Maestas, who ran for office using public financing, said, “Not having to spend time dialing for dollars allowed me to really spend time knocking on doors instead.”

Former Arizona State Representative John Loredo, observing his peers running under the public financing program in Arizona, said that “If you were running against someone who was not using public financing, they were not out knocking on doors, they were stuck sitting at a desk calling lobbyists to raise money. Clean elections candidates were at a huge advantage because they were able to get out in the neighborhood walking and knocking, and connecting with voters.”

When big donors are not dictating the agenda, elected leaders are free to address the concerns that actually impact the daily lives of constituents. In Connecticut, for example, following the introduction of a public financing program, legislators were able to pass paid sick leave, a policy that had long been held up by business interests despite widespread public support.

While talking about the potential of Democracy Dollars to transform the way elected leaders govern in Albuquerque, Mayor Tim Keller said, “What is the policy that helps everyday people? That’s the discussion we are missing. That is the discussion that we will have to have if we pass Democracy Dollars, and that is a discussion that we need to have to have a vibrant democracy in Albuquerque.”

In order to achieve an inclusive democracy that responds to the needs of all constituents, regardless of their ability to write large checks, we need a campaign finance system that incentivizes candidates to spend time with regular constituents.

Breaking Down Barriers for Candidates from All Backgrounds

By allowing candidates to run on the strength of their local support, not their ability to raise large gifts, small-donor public financing increases the ability of candidates from all backgrounds to run for city office. Democracy Dollars would break down barriers that too often prevent qualified candidates from running for office, by providing candidates without access to high-income donors an avenue to compete.

Candidates across the country credit public financing programs for giving them a shot at running, even if they lacked access to big donors. Gary Winfield, State Senator and Assistant Majority Leader in the Connecticut legislature, said, “Without public financing, I would not have been a viable candidate…I didn’t come from money. I am a candidate of color, and I wasn’t a candidate for the political party or machine apparatus.” New York Attorney General Letitia James who previously ran for and was elected New York City Public Advocate as a publicly-financed candidate said, “I come from a hardworking family, but not a wealthy one. When I ran for office, I did not know millionaires, and I did not know those with deep pockets—but I knew those who wanted to have a voice in government and have a seat at the table. The public financing system in New York City gave me the opportunity to compete and succeed, allowing me to represent individuals whose voices are historically ignored.”

In Seattle, time and time again candidates have credited the Democracy Vouchers program for opening the door for them to run for office. First-time candidate Teresa Mosqueda, who ran for city council in Seattle, acknowledged the Democracy Voucher program for “making it possible” for her to run for office. Before running and winning office, Mosqueda was a labor activist in the city who worked to help raise the state’s minimum wage. Another Seattle city council candidate, Shaun Scott said, “Democracy Vouchers are a way for candidates who would never be able to run, especially working-class candidates and candidates of color like myself, to not only be competitive but to win and deliver real material change to Seattleites who need it most.”

When our elected officials are more reflective of the communities they represent and enter office with a diverse array of lived experiences, the full spectrum of concerns facing their constituents has a better chance of being addressed. Strengthening Albuquerque’s small donor public financing program with the addition of Democracy Dollars is a key means to ensure inclusive democracy.

Conclusion

As in most places in the United States, big money threatens to undermine Albuquerque’s democracy. Albuquerque’s elections are dominated by big-donor giving, and the people who fund elections do not reflect the city’s residents. Albuquerque’s existing public financing program is a pioneering initiative with an important goal of freeing candidates to run for office with the financial backing of regular Albuquerque residents. However, following Supreme Court interference that sided with pro-business interests and opponents of campaign finance reform to weaken such programs across the country, candidate participation in Albuquerque’s program declined, particularly in mayoral races. Donors of $1,000 or more can and do contribute the vast majority of funds to candidates, and the donor class is whiter, higher-income, more male, and older than the city’s population. Strengthening Albuquerque’s public financing program with the addition of Democracy Dollars has the potential to diversify and expand the city’s donor base, increase reliance on average constituents to fund campaigns, and give typically marginalized residents a bigger say in local policy making. Albuquerque residents from all walks of life deserve a voice in the decisions that impact their daily lives. Fortunately, during the next election they will have the chance to vote for Democracy Dollars and put their city at the forefront of democracy reform.

Acknowledgments

This report was produced in collaboration with Tam Doan, Senior Fellow at the Center for Popular Democracy and Eric Griego, State Director at the NM Working Families Party and former Albuquerque City Councilman. The authors would like to thank Laura Williamson, Senior Policy Analyst at Demos, Mark Huelsman, Associate Director of Policy & Research at Demos, and Jesse Rhodes, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, for their support in data analysis and editing.