New Report on Voter Language Access Finds Gaps, Successes, and Opportunities in Voting Rights Act and State Policies

Federal language access laws do not fully address the American electorate’s diverse language needs

Today, Dēmos, a nonprofit public policy organization, released a report highlighting successes in federal laws addressing language access for voters, while naming shortcomings that must be addressed in order to strengthen voters’ ability to shape democracy.

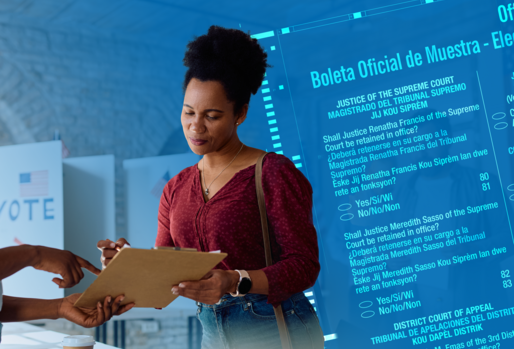

The report, titled Language Access and Voting Rights: An Overview of Federal, State, and Local Policies, details essential contributions from the Voting Rights Act (VRA) and commendable efforts from some jurisdictions where officials are meeting voters’ language needs—in some cases by going well above the VRA’s requirements. But the report also identifies gaps in national, state, and local voting laws that leave thousands of voters behind.

“Barriers to the ballot based on language skills have long been a part of the anti-voter playbook, and our federal language access laws have not done enough to protect voters,” said report author Angelo Ancheta, Senior Research and Policy Counsel at Dēmos. “From the literacy tests of the Jim Crow era to state-imposed English-only election materials of the modern day, linguistic barriers have a long history of leaving voters, particularly voters of color, without adequate access to the ballot.”

The report’s analysis of current language access laws makes clear that local and state policymakers must take action and expand voting access through language assistance policies and practices.

“Language access is a racial equity issue,” said Phi Nguyen, Director of Democracy at Dēmos. “As they currently stand, federal language access laws often fail to protect voters and leave out thousands of voters of color because of their language proficiency level. As we’ve already seen in many states and localities across the country, enacting policies to better address the diverse language needs of American voters can address inequities in ballot access and ensure that our democracy is working for our communities.”

One shortcoming named in the report is that federal mandates under the VRA have resulted in only a patchwork of services nationwide. As a result, thousands of limited-English-proficient voters throughout the country have been left with little or no assistance. The technical legal reasons for this are that either these voters fall outside the VRA’s definition of “language minority” or because their population numbers, while large and growing, fail to satisfy the VRA’s mathematical formulas for triggering coverage.

Still, the report commends some jurisdictions that have made clear efforts to meet voters’ language needs beyond federal requirements, and the report draws on many of these efforts in recommending best practices. The report’s recommendations include creating election materials in languages other than those required under federal law, lowering thresholds for language assistance to be offered below the federal triggers in order to expand the number of voters assisted, and employing clear compliance mechanisms that draw on both sufficiently funded government policies and strong community input.