After getting the First Amendment supremely wrong in Citizens United, the Supreme Court now faces its next money in politics case. In McCutcheon v. FEC, the challengers are attacking a law that says that no one person can contribute over $123,000 directly to federal candidates, parties, and committees—that’s over twice the average American’s income. The Supreme Court has previously upheld these contribution limits because they fight both the reality and the appearance that our democratic government is corrupted by the improper influence of big money on politics and policy. After all, in a democracy the size of your wallet should not determine the impact of your voice or your right to representation.

We don’t need the Court to do any more damage to our democracy. Shaped by the Court’s past decisions, the current system of campaign finance already allows a minute percentage of wealthy Americans, the donor class, to dominate our elections. If the Court strikes these limits, a single wealthy donor could contribute more than $3.5 million to one party’s candidates and committees. And, elected officials could solicit multi-million dollar checks from a single donor, providing greater incentive for candidates—and office holders—to grant these donors improper influence.

A diverse array of groups representing almost 9.5 million Americans have come together on a brief authored by Demos to tell the Supreme Court—and our elected representatives—that Americans are outraged about the impact of money on the integrity and responsiveness of the United States government. These groups include the four principal conveners of the Democracy Initiative—Communication Workers of America, Greenpeace, the NAACP, and the Sierra Club—as well as the Main Street Alliance representing small business, Our Time and Rock the Vote representing young people, the American Federation of Teachers and Working Families Organization representing working families, and People for the American Way and U.S. PIRG representing the public interest. The following is a summary of the brief’s major points.

“Limitations on money in politics prevent the real or imagined coercive influence of large financial contributions on candidates’ positions and on their actions if elected to office.”—Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 26-27(1976) (per curiam).

“Take away Congress’ authority to regulate the appearance of undue influence and the cynical assumption that large donors call the tune could jeopardize the willingness of voters to take part in democratic government."—McConnell v FEC, 251 F. Supp. 2d 176 (D.D.C.) aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 540 U.S. 93, 144 (2003). Internal citation omitted.

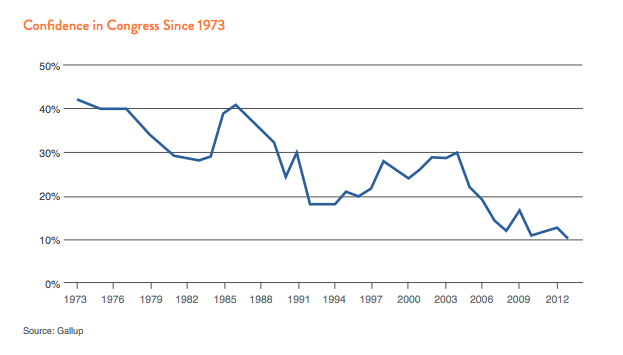

Americans’ confidence in government is at an all-time low.

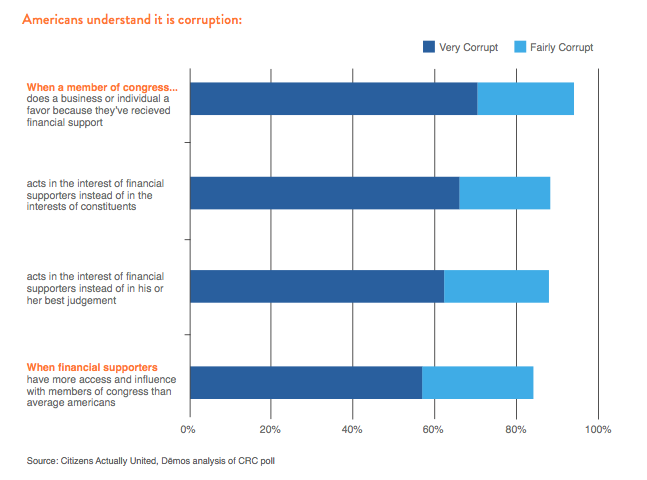

The Court has consistently cited the danger that interdependent relationships between elected officials and financial supporters pose to representative government. Legitimacy is essential for a functioning democracy, and it rests on the belief by the people that they are fairly represented. Americans know that financial supporters currently have an improper influence on our politics and policy, and they understand that this is corruption of democratic government. Elected representative have a duty to act with care and integrity in the interests of all their constituents, and the country as a whole, and not to favor the positions of their financial supporters.

Even in Citizens United, Justice Kennedy recognized that:

“[i]f elected officials succumb to improper influences . . .; if they surrender their best judgment; and if they put expediency before principle, then surely there is cause for concern.”

There is more than just cause for concern. American’s confidence in Congress is down to 10 percent—the lowest level of confidence for any institution on record since Gallup began asking this question in 1973. A majority of the American public, 52 percent, has little or no confidence in Congress.

Since 1953, the National Election Survey has asked three questions pertaining to corruption in government from which they calculate the Trust in Government Index. The last index, in 2008, tied with the prior low in 1994; since then these responses have all worsened. Eighty-six percent of Americans are worried about corruption of government, and 82 percent of Americans are worried about special interests buying elections.

Americans believe their Representatives are more responsive to big donors than to voters and the improper influence of money on government blocks it from working to solve our common problems.

Americans across the political spectrum believe that money in politics is the reason their representatives are more responsive to private interests with financial resources than to the public interest. Sixty percent of Americans say Members of Congress are more likely to vote in a way that pleases their financial supporters, while only twenty percent think Representatives will vote in the best interests of their constituents.

Nearly three-quarters of voters—73 percent—thought that the influence of campaign money was a “major factor in causing the current financial crisis on Wall Street.“ Responses between Republicans and Democrats were nearly identical, 74 percent and 76 percent respectively. They thought large campaign contributions from the banking industry led to lax government oversight of the industry. And, Americans recently reported feeling that the federal government “is so corrupted by big banks, big donors, and corporate lobbyists that it no longer works for the middle class.” Americans fear that this improper influence from private economic interests is preventing government from acting to address their real problems.

Almost eighty percent of Americans agree with the statement:

“I am worried that large political contributions will prevent Congress from tackling the important issues facing American today, like the economic crisis, rising energy costs, reforming health care, and global warming.”

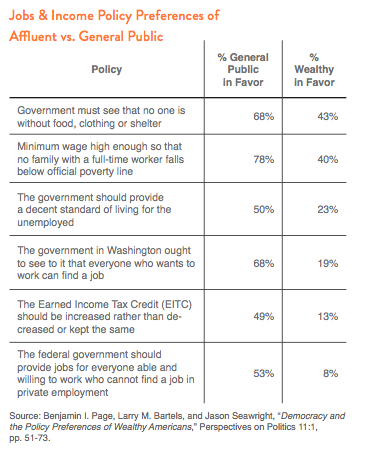

Government responds to the policy preferences of the donor class even when they differ starkly from the American public—particularly on economic issues.

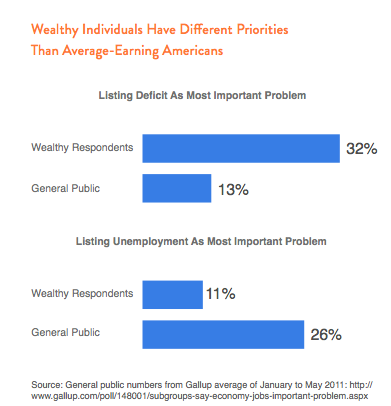

New research confirms F. Scott Fitzgerald’s observation that “the rich are different from you and me.” They have starkly different policy priorities than the general public, especially on economic issues. And government in the U.S. responds differentially—often dramatically so—to the preferences of the donor class, even when those preferences run counter to those of the general public. Campaign finance is a significant factor in this dynamic.

The differing preferences of the wealthy from the general public has been documented on many important policy issues—especially on key questions about how to structure the economy and respond to America’s economic needs. Recent research, including the 2011 study Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans finds significant differences across a range of issues related to economic well-being and the role that government should play in the economy. For example, a full two-thirds (68 percent) of the general public believes that “the government in Washington ought to see to it that everyone who wants to work can find a job.” But among the wealthy respondents in the Policy Preferences study, only 19 percent agreed with that statement—a disparity of more than 3 to 1. Similarly, 78 percent of the public supports a minimum wage high enough that no family with a full time worker falls below the poverty line, while only 40 percent of the wealthy agree. That is a nearly 2 to 1 disparity.

The general public is far more concerned with job creation and economic growth than with reducing the deficit, sometimes by double-digits. In contrast, for the high-wealth subjects of the Policy Preferences study asked to name the most important problem facing the country, “[o]ne-third (32 percent) of all open-ended responses mentioned budget deficits or excessive government spending, far more than mentioned any other issue.” Respondents were far more likely to favor cutting spending on programs such as Social Security, Food Stamps, and health care than was the general public, which instead would prefer to see expanded government spending on such programs.

The differing policy preferences of the wealthy as compared to the general public would not present a challenge to the democratic vision of a representative government if the actual influence of the wealthy on public policy accorded with their numbers. But the degree to which a small cohort of Americans that contribute large sums to federal campaigns exerts a strong influence on the political process and public policy outcomes should be sobering to anyone concerned with the health of our democracy.

In the study Affluence and Influence, Professor Martin Gilens examined the extent to which the policy preferences of different income groups are reflected in actual policy outcomes in the United States, and found that average Americans have little influence when their preferences diverge from those of the affluent:

“The American government does respond to the public’s preferences, but that responsiveness is strongly tilted toward the most affluent citizens. Indeed, under most circumstances, the preferences of the vast majority of Americans appear to have essentially no impact on which policies the government does or

doesn’t adopt . . . The complete lack of government responsiveness to the preferences of the poor is disturbing and seems consistent only with the most cynical views of American politics . . . median-income Americans fare no better than the poor when their policy preferences diverge from those of the well-off."

These findings challenge the vision of American democracy in which government of, by, and for the people responds to the will of the majority: when the preferences of the wealthiest ten percent conflicts with the rest of Americans, the views of ten percent trumps the ninety percent. This is supported by other research. The 2008 study, Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age, found that “[t]he preferences of people in the bottom third of the income distribution have no apparent impact on the behavior of their elected officials.”

Elected representatives are more dependent on a tiny fraction of the wealthy for financial support than ever before.

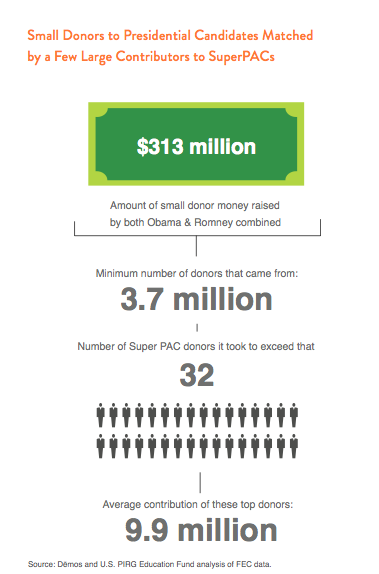

Already, American elections are dominated by a wealthy elite, with the improper influence and dependence that that entails. Candidates have relied on large donors for campaign funding before, but the dominance by a tiny fraction of the U.S. population over contributions and spending in support of candidates has escalated in recent years. Indeed, the Sunlight Foundation reported that in the 2012 elections “candidates got more money from a smaller percentage of the population that any year for which we have data.”

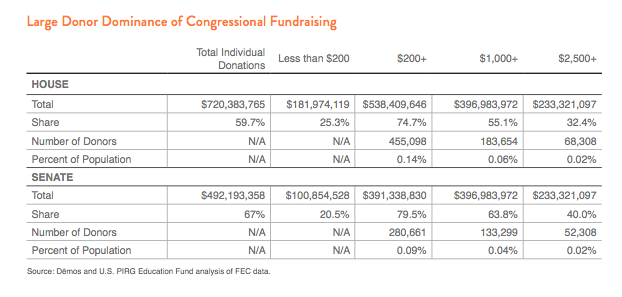

Unsurprisingly, the affluent are far more likely to make financial contributions than are other Americans. Only .4 percent of the American population made a disclosed federal contribution of over $200 in 2012, whereas two in three (68 percent) wealthy respondents had made political contributions in the past year. Just 0.07 percent of the U.S. population made campaign donations of $2,500 or more in 2012.

In the 2012 elections, over a quarter of all of the identifiable political contributions to any candidate, party, committee, or group came from just 31,385 people—one ten-thousandth of the United States population. The impact of this tiny group of Americans is clear: 86 percent of the members elected to Congress (372 of 435) and more than half of the members elected to the Senate in 2012 (20 out of 33) received more money from the 1 percent of the 1 percent than from all their small donors combined. According to the Sunlight Foundation “not a single member of the House or Senate was elected without financial assistance from this group.”

Further, “[t]he nations’ biggest campaign donors have little in common with average Americans. They hail … from big cities, such as New York and Washington. They work for blue-chip corporations, such as Goldman Sachs and Microsoft. One in five works in the finance, insurance and real estate sector. One in ten works in law or lobbying.” The median aggregate contribution from this elite group was $26,584; this is more than half the median family income in the United States. Over 90 percent of donations come from majority white, wealthy neighborhoods while only four percent came from Latino neighborhoods, even though Latinos comprise 16 percent of the U.S. population. 2.7 percent came from majority African-American neighborhoods and less than one percent came from Asian neighborhoods.

Because our elected officials depend upon this tiny fraction of the wealthy elite, they spend their time contacting the donor class and hearing about their concerns and priorities. In describing the four to six hours of fundraising calls he’s required to make per day, Senator Chris Murphy noted that he wasn’t calling anyone “who could not drop at least $1,000,” who he estimated make at least $500,000 to $1 million per year:

“[Those making between $500,000 to $1 million] have fundamentally different problems than other people. . . And so you’re hearing a lot about problems that bankers have and not a lot of problems that people who work at the mill . . .have. You certainly have to stop and check yourself.”

Americans across the political spectrum oppose the capture of elected representatives by financial supporters and demand solutions to the improper influence of money on government.

It is no wonder that Americans’ confidence that government is able to respond to important public needs by resisting the improper influence of campaign money is eroding. This phenomenon is driving a significant percentage of the public away from political engagement. Even in 2008, an election with record turnout, 80 million eligible persons failed to participate. In a poll of eligible persons who stated they were unlikely to vote, when asked why they did not pay attention to politics a majority (54 percent) said “[i]t is so corrupt.” As citizens lose faith in government, levers of democratic accountability are dismantled, and we lost the wisdom of the larger electorate in determining the direction of our nation.

Despite their concerns about the impact of campaign money on the integrity of their government, Americans have not given up on the belief that limiting the size of contributions is an important answer. Nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of all voters believe there should be common-sense limits on the amount of money people can contribute to political campaigns. A large majority of Americans, 60 percent, say “candidates ought to tackle money in politics in order to make government work for the middle class.”

The Court should refuse to exacerbate fundraising dynamics that pressure elected representatives to favor the policy preferences of those they depend on for financial support. Elected officials are frequently raising money from the very interests they are charged with regulating—and which they must regulate effectively in the public interest. Those in positions of economic power can use their financial resources to support their favored politicians, and in turn elected officials can use their political power to further the economic interests of their financial supporters. This can lead to capture of government by private economic interests, in derogation of the duties of elected representatives to act in the interests of their constituents and the country as a whole. To prevent the crisis in confidence in American democratic government from worsening, the Court must uphold the contribution limits challenged in McCutcheon v FEC.