Why New Yorkers Know Their Rights—and We All Should

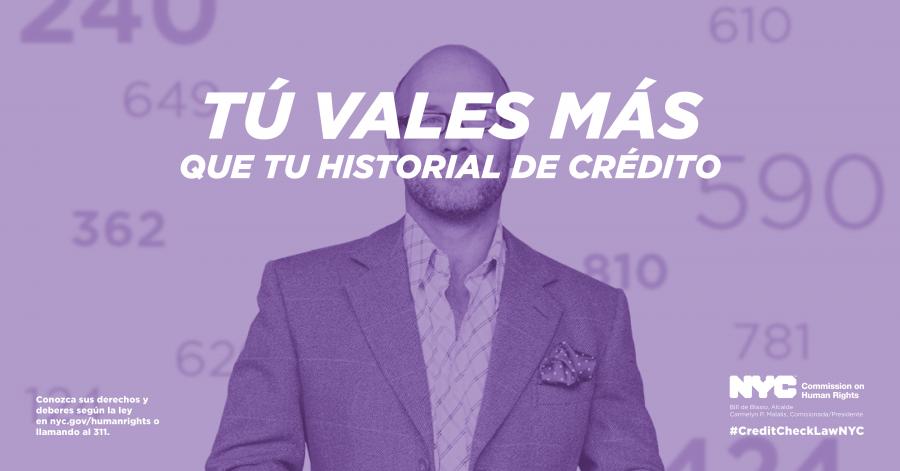

OU SE PLIS PASE ESKÒ KREDI OU. I can’t read the words either. But for the more than 100,000 New York City residents who speak Haitian Creole, it represents the City’s commitment to inform New Yorkers – all New Yorkers – of their rights. In this case, their right to apply for and work at a job without an employer demanding a look at their personal credit history. The alert is available not just in Haitian Creole but in all ten of New York’s most spoken languages. And it’s joined by ads on buses, in the subway, and on the covers of the commuter papers, as well as flyers, trainings, and an extensive website.

Demos is proud to have worked with allies at the New Economy Project, NYPIRG, DC 37, RWDSU, legal services groups throughout the city, and many other organizations to enact the nation’s strongest law banning employment credit checks, a practice which we have found to be a serious barrier to economic security for job applicants, with a potentially discriminatory impact on people of color, who have been disproportionately targeted by predatory lending that can destroy credit.

Now, as New Yorkers, we’re also proud of the city’s commitment to raise public awareness of not just the Stop Credit Discrimination in Employment Act but other critical rights as well. Last month, the Fair Chance Act went into effect, making it illegal for most employers in New York City to ask about the criminal record of job applicants before making a job offer. As the City’s Commission on Human Rights explains “this means ads, applications, and interview questions cannot include inquiries into an applicant's criminal record. This allows the applicant to be judged on his or her qualifications.”

The Commission on Human Rights is tasked with enforcing both laws, as well as the rest of New York’s far-reaching human rights law that prohibits discrimination based on race, religion, color, age, national origin, citizenship status, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, pregnancy, marital status and more. Under the direction of Commissioner Carmelyn Malalis, who has been in office a year, the Commission is broadening investigations to address systemic discrimination, is offering more training to small businesses and housing providers, and has engaged in high-profile public awareness campaigns around the Fair Chance Act and the Stop Credit Discrimination in Employment Act.

Public awareness is critical because if job seekers and employees don’t realize they have the right to seek work without being interrogated about their personal credit history, criminal record, pregnancy status, or other factors not relevant to the job, they may be impacted by discrimination without ever realizing it. As Sean McElwee and I find in a forthcoming paper, many states that enacted laws restricting employment credit checks failed to take the aggressive steps New York has committed to informing job applicants and workers of their rights. Perhaps, as a result, few people have come forward with complaints under the laws. Without awareness of rights, laws on the books might as well be a dead letter. Educating employers about their rights and responsibilities is essential for the same reason. One need only look at the uproar caused by a proposed rule to inform workers of their 70+ year-old right to join a union to see just how powerful a little awareness can be.

“Criminal Record? You can work with that” announces the accessible ad campaign the firm Bureau Blank designed to promote awareness of the Fair Chance Act. But without the commitment to public outreach, New Yorkers would never know it. To make all our rights a reality, people across the country deserve the same commitment to public awareness.