Want to Help Struggling Student Loan Borrowers? Start with Bankruptcy Reform

In a week when President Trump proposed deep cuts to programs that help students afford and complete college, Senator Dick Durbin and 11 Senate Democrats offered some better news by reintroducing a bill that would restore the ability of private student loan borrowers to discharge their loans in bankruptcy proceedings. Were it to become law, it would be a welcome step forward for struggling households, and a recognition that in a world where most students must borrow for a credential, borrowers should receive the same failsafe protections on these loans as they do on any other consumer loan.

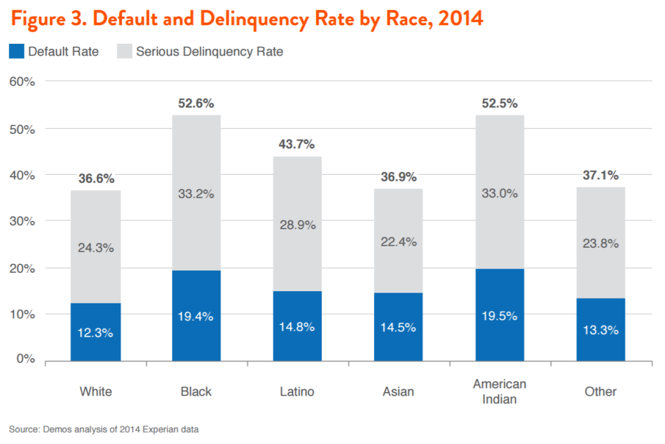

Opening up the bankruptcy option also makes sense when you consider that for all our efforts creating income-driven repayment and loan forgiveness programs, not to mention forbearance and deferment options for student borrowers, student loan delinquency and default rates remain stubbornly high, particularly for borrowers of color.

And according to the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, troubled borrowers often default on the same loan more than once, in part due to program complexity and poor servicing, and despite the option of multiple plans that could lower their monthly payments. In short, student debt is unnecessarily sticky for some, and current relief efforts have not come close to helping everyone who needs it.

The current situation for borrowers—in which student loans are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to offload in bankruptcy—is a result of bad policy starting in the 1970s and relentless lobbying by lenders in the mid-2000s.

Until 1978, borrowers could relieve both federal and private student loans in bankruptcy, but Congress began to treat federal student debt far less favorably than other types of loans. Spurred on by a few anecdotes of graduate students borrowing and declaring bankruptcy with years ahead of them to rehabilitate their credit, lawmakers created a new standard for dischargeability—“undue hardship”—that was never properly defined. In return, courts have set an extremely high and often arbitrary bar for borrowers, so much so that the overwhelming majority of those already entering bankruptcy proceedings who have student loans do not seek to discharge them.

In 2005, the Bush administration and lawmakers were swayed by private loan companies to extend the policy to private loans. This was outrageous on its face; private student loans can more closely resemble credit cards than federal student loans, and do not come with the same protections as federal loans in terms of deferment, forbearance, subsidized interest, and more generous repayment terms.

It was also a response to an entirely phantom problem. Just as there had been no large-scale evidence in the 1970s that students were abusing the bankruptcy code with regard to federal loans, a later study from the Philadelphia Federal Reserve also showed that there was no evidence of “widespread opportunistic behavior by private student loan borrowers before the policy change” in 2005. To their credit, the Obama administration asked Congress in 2015 to roll back the law for private loans, but got no response from the GOP majority. To date, President Trump has been silent on the issue, despite his delight in discussing his mastery of the U.S. bankruptcy code.

This is important today for a few reasons. First, while the private student loan market was decimated during the Great Recession, use of private loans has begun to tick back up in recent years. And according to the Institute for College Access & Success, almost half of all private loan borrowers are not exhausting federal loans before opting for the riskier option. Use of private loans is higher among students in the for-profit sector, especially troubling given the frequency with which borrowers at for-profits to drop out with debt or default on their loans.

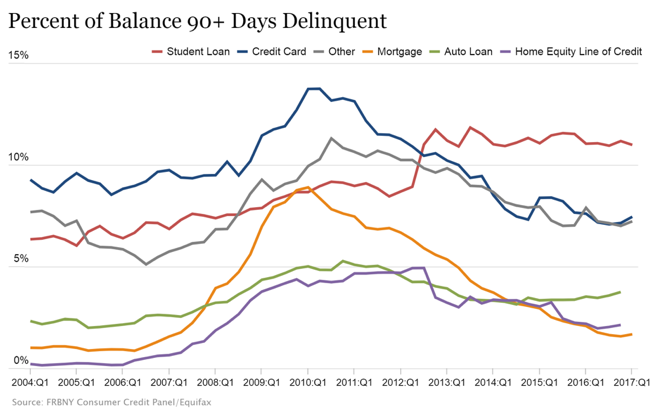

Second, while overall household debt is once again reaching the pre-recession peak, student loans are making up a larger piece of the pie. And if student debt or other factors are delaying some borrowers from purchasing homes or cars, it may be that for those households it’s the only meaningful debt that they carry. But since default and delinquency are uncomfortably common, this doesn’t necessarily mean that these households are well-off. In other words, borrowers should not have to wait until they also rack up unpayable credit card, medical, or housing debt to avail themselves of the bankruptcy process. If student debt is increasingly hard to discharge, truly troubled borrowers may not seek the bankruptcy route even if it offers the most humane option available to them.

And finally, the Trump administration has taken a number of steps that promise to make it harder, not easier, for struggling borrowers or those seeking forgiveness. In addition to proposing an end to Public Service Loan Forgiveness and subsidized student loans, Secretary Betsy DeVos has rescinded Obama-era memos that would put more incentives in place for loan servicers to help struggling borrowers.

Meanwhile, thousands of students who were promised loan relief after being defrauded by predatory colleges have been in a state of limbo as the Department of Education has slowed the review process for their claims, and the GOP has repeatedly threatened to gut the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, leaving the private loan market without a cop on the beat.

Rather than limiting loan forgiveness options and ignoring struggling borrowers, we should be re-opening an option that existed and worked just fine. Bankruptcy is not an easy process—and claims would still be subject to court approval, reducing any worry about young people “gaming the system”—so it makes little sense for us to treat private or federal loans differently than we do credit card or medical debt. Bankruptcy protections may not solve the student debt crisis for everyone, but by definition, they would benefit those for whom student debt has truly become an albatross.