For My Mom, Voting Took a Village

For many immigrants in the United States, voting can be a daunting and unfamiliar process. Explore my family's journey of overcoming language barriers and navigating a complex voting process to help my mom vote for the first time.

My mom voted for the very first time in the 2016 presidential election at the age of 64, despite having lived in America for nearly 40 years. After enduring an oppressive regime in Vietnam that imprisoned several of her family members for their political affiliations, my mom avidly avoided politics in America. And in turn, politics avoided her. No bright-eyed canvassers ever knocked on our door to ask her if she had a plan to vote. No enthusiastic volunteers ever called our landline to remind her of an upcoming voter registration deadline. No colorful flier featuring a smiling candidate ever landed in our mailbox, waiting to be studied by my mom. After so many elections had come and gone with little fanfare, persuading her that her voice in this election mattered took a village. Over the course of several months, my sisters and I pleaded with our mom—in our halting Vietnamese—about what was at stake. Finally, she acquiesced. But convincing my mom of the importance of her vote was only the first obstacle that stood between her and the ballot box.

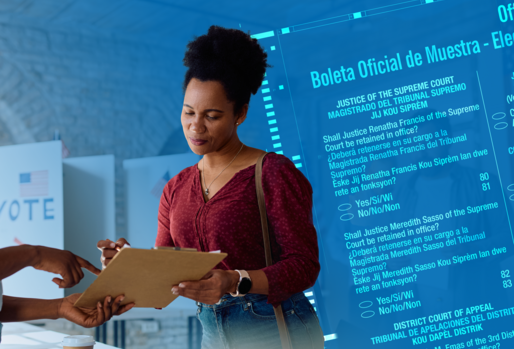

My mom’s native language is Vietnamese. She did not attend school or work outside of the home in the U.S., so her English is limited. In her county of residence, Columbia County, Georgia, ballots are only available in English—as is the case nearly everywhere in Georgia and in most other states. But the option to vote by mail helped her push past her worry about voting in a language she does not fully grasp. She took comfort in knowing she would be able to complete her ballot in her own home at her own pace, while one of her daughters helped her navigate the English ballot.

Though she had not done anything wrong, my mom felt humiliated and ashamed. She returned home and sent me a text to let me know she had tried to vote but failed.

Unfortunately, my mom misplaced her vote-by-mail ballot before she could turn it in. On Election Day, she went with my dad to their precinct to cast a ballot in person instead. But poll workers turned her away, instructing her she would need to first go to the county election office to cancel her vote-by-mail ballot. Though she had not done anything wrong, my mom felt humiliated and ashamed. She returned home and sent me a text to let me know she had tried to vote but failed.

Had I still lived in the same town as my mom, I would have driven her to the county election office and then back to the polls to help her through the process. But I was 150 miles away in Atlanta, as were all of my sisters. My dad had gone to work for the day and wasn’t around to help her either. So I called the one person I knew could help—my friend, Raymond Partolan. In 2016, Raymond was leading the civic engagement program at Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Atlanta, which was at the time the only Asian American civil rights organization in Georgia. After I spoke to Raymond, he immediately called my mom’s polling place to confirm with a poll worker that she could return to vote in person if she signed an affidavit declaring she had lost her vote-by-mail ballot. Raymond then lined up a Vietnamese interpreter who could stay on the phone with my mom to assist with any communication challenges she might encounter.

Meanwhile, I went about the Herculean task of convincing my mom that she had done nothing wrong and that she wouldn’t be turned away again if she returned to the polls. Before heading back, my mom texted me from the parking lot: “If they don’t let me vote, I will kill you.” Fortunately, moments later, I received a blurry picture from my mom of her “I’m a Georgia Voter” peach sticker, signaling that she had successfully cast her very first vote and I could live another day.

My mom would not have voted in 2016 had she not had a team of people to first convince her that her vote mattered and then help her navigate the process of registering to vote and casting a ballot.

My mom would not have voted in 2016 had she not had a team of people to first convince her that her vote mattered and then help her navigate the process of registering to vote and casting a ballot. Her lived experience as a political refugee already made her shy away from politics. And the lack of language assistance available for limited English proficient (LEP) voters like her only reinforced doubt about her role in our democracy. While someone more familiar with voting may have experienced being turned away at the polls as only a minor though frustrating setback, for my mom, it was unsettling.

My mom’s story is far from unique. Instead, it illustrates the barriers to political participation that challenge millions of immigrants in the U.S.—even those who, like my mom, have called America home for many decades. According to Census Bureau data, roughly 26 million Americans are LEP. Currently, a patchwork of federal, state, and local laws provides for some language assistance in elections. But thousands of Americans remain without meaningful opportunities to cast a ballot because of a persistent underinvestment in language access. Lack of robust language access policies is one factor contributing to consistently lower electoral participation among Asian American and Latino communities.

Worse still, some states are taking steps to actively exclude immigrants from any political participation. In the absence of any government-provided language services, my mom relied on help from family members and trusted community members to vote for the first time. This reliance on community is critical for so many LEP voters. Yet in recent years, states have begun attempting to restrict whom voters can turn to for help navigating the voting process. Florida, for example, passed a law, S.B. 7050—which Dēmos and partners successfully blocked—that sought to impose a $50,000 fine on organizations for each noncitizen person who “collected” or “handled” voter registration forms on their behalf.

S.B. 7050 targeted organizations dedicated to increasing electoral participation and civic engagement among immigrant communities. This type of work often relies on trusted community representatives with linguistic and cultural knowledge to meet people where they are. Sometimes those trusted community representatives may not themselves be U.S. citizens. Take, for example, Raymond. Despite not being eligible to vote himself—or perhaps because of this—Raymond has, since high school, worked to build power for immigrant communities. In 2016 alone, he helped 11,000 Georgians—mostly from immigrant communities—become registered voters. And without him, my mom would not have voted for the first time.

While immigrants face many barriers to political participation, language assistance is one critical way to invite more immigrant voters into the process.

Where states are not actively thwarting efforts to civically engage immigrants, there is, at best, little investment in their political participation. The weakness of existing language access policies reflects this underinvestment. While immigrants face many barriers to political participation, language assistance is one critical way to invite more immigrant voters into the process. We need more robust local, state, and federal policies to ensure that LEP voters have access to translated voting materials, interpreters, and informed poll workers. Unlike my mom, most LEP voters do not have a team of five eager daughters, a friend who is a voting rights expert, and a dial-by-phone interpreter who can help them vote from start to finish. And if policymakers invested in more policies that support and facilitate the civic engagement of immigrant communities, LEP voters wouldn’t need such a team in the first place.

To read Dēmos’s latest report surveying local, state, and federal language access policies and providing policy recommendations, click here. To read about Dēmos and its partners’ successful efforts blocking Florida law S.B. 7050, click here.

Phi Nguyen is the Director of Democracy at Dēmos. Learn more about her and read more of her published work here.