Motor Vehicle Departments Are Asleep at the Wheel on Voter Registration

States around the country are making registering to vote through the DMV more cumbersome and difficult than federal law allows.

Picture this: You go to the Department of Motor Vehicles to apply for a driver’s license. You complete an application that contains your name, address, data of birth, citizenship, and social security number. You provide multiple proofs of address and identity. Then you come to a box asking whether you want to register to vote. Why not? You are already giving the DMV all the information needed to register. It should be easy, right?

Not in California (or some other states, too). In California, if you want to register to vote at the DMV, you must fill out a separate voter registration form and provide all the same information the DMV already has on file. Then, if you are lucky, the DMV will pass the voter registration form on to the county voter registrar who will put you on its list of eligible voters. I say “if you are lucky” because many in California have jumped through all of the DMV hoops only to find that they are not on the voter rolls on Election Day.

Shelley Small is one of those who was not so lucky. Small is 62 years old and had never missed an election in 43 years. In 2014, she moved from one part of Los Angeles County to another. She went to the DMV to update her driver’s license. Under federal law, Small should not have needed to do any more for her voter registration to be automatically updated, but she wanted to be sure, so she specifically asked about updating her voting address. The DMV told her they would take care of it. But when Small went to the polls on Election Day, as she had done on every Election Day since she was 19, she was told she was not on the list of eligible voters and was turned away, unable to vote.

Those are some of the reasons Demos, along with several other voting rights groups, sent a letter to the California Secretary of State today notifying him of problems with voter registration at the DMV and warning him that the State faces litigation under the National Voter Registration Act, known affectionately as “Motor Voter,” if it does not fix them.

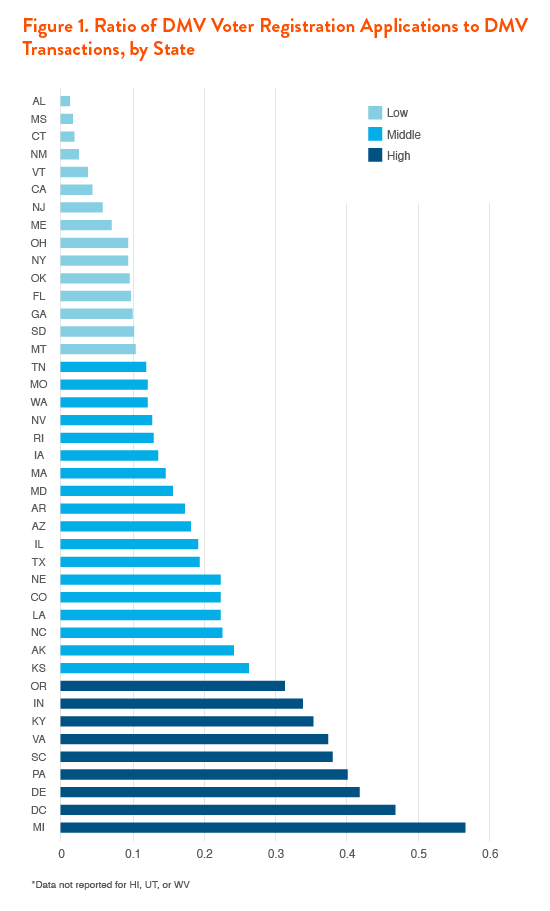

California is not alone in neglecting its Motor Voter obligations. As Demos explains in its new report, Driving the Vote, and as last years’ Presidential Commission on Election Administration highlighted, states around the country are making registering to vote through the DMV more cumbersome and difficult than the law allows. Some are diverting voters to elections officials rather than offering registration themselves as Motor Voter requires; others, like California, make voters fill out completely separate driver’s license and voter registration forms that require exactly the same information, doubling the effort required to register. Even worse, some states cancel the voter registrations of voters who report a change of address to the DMV instead of updating their voting address as required by federal law. The result: in many states, DMVs are registering only a tiny fraction of the voters they interact with.

The good news, as we explain in the report, is that there are many low-cost options available to states to make registering to vote a seamless and painless part of applying for a driver’s license. In some places, once you’ve checked that box saying you want to register, you’re done. You might have to sign to affirm that you are eligible and pick a political party, and then the driver’s license application itself is processed as a voter registration application. In others, DMV workers ask if you’d like to register when you hand in your driver’s license application, and if you say “yes,” they transfer your information to the voter registrar electronically. Several states, such as Michigan and Delaware, are already doing these things, and it shows in the number of voters who register via their DMVs.

Streamlining voter registration at DMVs could have a huge impact on voter registration rates across the country. If the states that register fewer voters through their DMVs increased their DMV voter registration activity to the level of the states with a more seamless voter registration process, we could see as many as 18.4 million more voter registration applications submitted through DMVs. Better Motor Voter compliance could have a particularly dramatic impact on voter registration rates among voters of color and young voters, who are registered at a much lower rate than white and older voters but who interact with the DMV just as frequently.

If DMVs were truly a true one-stop shop for driver’s licenses and voter registration as Motor Voter intended, it could drive voter registration to new heights. Until then, we will see too many states like California: full of drivers with no say in where they are going.