Executive Summary

For our democracy to thrive, the freedom to vote must be fiercely protected for all citizens, regardless of class or privilege. Yet, much work needs to be done to ensure our election system works for all Americans, particularly regarding the accessibility and ease of navigation of the voter registration process. Historically, and still to this date, the number of eligible Americans who are registered to vote remains stubbornly low, ranging from 60 percent to 75 percent in presidential election years, which in turn leads to depressed voter turnout rates that skew our electorate and undermine representative democracy.

In 1993, Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act (“NVRA”) with the goal of increasing voter participation in elections by requiring states to make voter registration more accessible. One of the key provisions of the NVRA, known as “Motor Voter,” requires state motor vehicles departments (“DMVs”) to incorporate voter registration into the driver’s license application, renewal and change-of-address processes. Despite the popularity of this mode of voter registration, the “Motor Voter” provision is not performing up to its potential, and, in many states, implementation of the statute’s requirements is severely wanting.

A. Motor Voter’s Potential

In the 20 years since the NVRA went into effect, the total number of voter registration applications originating at motor vehicle departments nationwide has remained fairly constant, despite our nation’s population increases during these years. That constancy, however, masks radical variations among states in the numbers of motor vehicle department transactions that result in a voter registration application. Based on an analysis of DMV transaction and voter registration data, Demos found that some states are generating voter registration applications from a large proportion of those who come into the DMV to obtain or update a driver’s license or ID card while in others, the DMV registers only a tiny fraction of voters engaging in licensing or ID card transactions.

Improved compliance with Motor Voter has the potential to increase these numbers dramatically. According to Demos’ analysis, over 18 million additional voter registration applications could be submitted through DMVs in a two-year period if lower-performing states increased their performance to the level of states at the 75th percentile (in other words, if they achieved a “C” grade).

B. Motor Voter in Practice

How states integrate voter registration into their driver’s license application, renewal, and change of address processes can have a dramatic impact on the number of voters who take advantage of the opportunity to register to vote. A handful of model states, whose DMVs are generating significant numbers of voter registration applications, have taken steps to ensure voters are aware of their opportunity to register to vote and have made the voter registration process simple and efficient for voters. Moreover, the most successful states typically use technology solutions to further streamline the process, reduce errors, and ensure voters remain registered when they move. On the flip side, procedures used by DMVs in many other states are failing to fulfill the promise and purpose of the NVRA. These states fail to make voter registration an integral part of driver’s license services and place the burden of registering to vote or updating their voter registrations on voters. Many of these states additionally fail to take advantage of technology infrastructure that already exists or could be implemented at low cost to improve the voter registration services offered by DMVs.

C. Improving Motor Voter’s Effectiveness

Drawing on the varying voter registration procedures used by DMVs in the best performing states, this report offers a set of model practices that appear to be the most effective in increasing voter registration rates at DMVs.

An effective DMV voter registration program will include one or more of the following key model voter registration procedures:

- A driver’s license application and renewal process that seamlessly integrates voter registration and does not require duplication of information.

- Electronic transfer of voter registration application data from the DMV to the elections office, including transfer of the voter’s signature.

- Automatic update of voter registration records when voters change their address, regardless of whether the voter has moved within or outside the county, unless the voter affirmatively indicates that the change is not for voter registration purposes.

- An offer of voter registration for individuals changing address with the DMV when the individual is not already registered.

- Assistance with the voter registration application.

As these model procedures suggest, for states to realize the promise of the NVRA, they must make registering to vote an integral part of obtaining a driver’s license or state identification card. The states that are most successfully implementing Motor Voter show that, by adopting common-sense procedures and relying on existing technologies, this goal is attainable. And when states achieve full compliance with Section 5, millions more Americans will have the opportunity to participate in our democracy.

I. Introduction

In 1993, Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act (“NVRA” or “the Act”) with the goal of expanding participation in the democratic process by making it easier for citizens to register to vote. In its first year of implementation over 30.6 million people submitted voter registration applications or updated their registrations through methods made possible by the NVRA. Fundamentally, the NVRA was designed to streamline and facilitate the process of voter registration and provide uniform registration procedures for federal elections. Under Section 5 of the NVRA, the “motor voter” provision that gave the Act its name, eligible citizens can register to vote or update their voter registrations when they apply for or renew a driver’s license. Any change of address submitted to the state motor vehicle office is also forwarded to election authorities, automatically updating the eligible voter’s registration.

Section 5 envisions a process allowing voters to register to vote with minimal additional effort beyond filling out a driver’s license application. Ideally, registration should require no more than choosing a political party affiliation, reviewing the voter qualifications, and signing a certification that the voter meets them—all on the same application form used to apply for the license. At a minimum, states are forbidden from asking voters to provide information already provided on the driver’s license application, such as name, address, and date of birth. Section 5 also requires states to update a voter’s registered address when the voter submits a change of address to a motor vehicles department (“DMV”), unless the voter affirmatively indicates that the address change does not apply to voter registration. This “opt-out” system of address updates is designed to ensure that voters are not inadvertently dropped from the voter rolls when they move, a vital protection for voters in our highly mobile country.

In the time since the NVRA’s initial implementation, when nearly half of NVRA voter registrations occurred through DMVs, DMV compliance with the NVRA and DMV effectiveness in registering driver’s license applicants to vote has, until recently, gone largely unexamined. In January 2014, Section 5 as well as other provisions of the NVRA received increased attention when the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, established by President Obama after the 2012 election, issued a report (“PCEA Report”) that ranked the NVRA as “the election statute most often ignored” and asserted that “DMVs . . . are the weakest link in the system.” In May 2014, Pew Charitable Trusts, in one of the first efforts to evaluate the PCEA Report’s findings, issued a report of its own assessing the available data on DMV compliance and began outreach efforts to DMV and elections directors on improving administration of DMV voter registration activities.

From January 2014 to November 2014, with support from the Democracy Fund, Demos carried out an exhaustive examination of DMV compliance with the NVRA. This examination had three components.

First, to establish a baseline understanding of the current level of voter registration activity at DMVs, we conducted an assessment in each state covered by the NVRA of DMV performance in registering voters who conduct driver’s license related transactions; and we identified target levels of DMV voter registration that could result from better implementation of Section 5.

Second, to pinpoint the key factors that contribute to lower or higher DMV voter registration performance across states, we carried out research into each NVRA state’s implementing laws, policies, and practices around voter registration at DMVs. Based on what we learned, we categorized voter registration practices used by DMVs in NVRA-covered states and analyzed the effectiveness of those practices in registering voters.

Third, based on this analysis, we devised a set of model voter registration procedures for DMVs that, given our current knowledge, appear best calculated to allow states to maximize the effectiveness of their Motor Voter programs.

Increasing the effectiveness of DMV voter registration programs has the potential to bring millions of additional Americans into the democratic process. By our estimates, better state compliance with Section 5 could potentially result in over 18 million additional voter registration applications being submitted through DMVs in each two-year election cycle.

II. Scoring Motor Voter

To explore the current level of voter registration activity under Section 5 of the NVRA, Demos analyzed existing publicly reported data to approximate the number of DMV transactions that result in a voter registration application being submitted. Specifically, using data reported annually by each state to the Federal Highway Administration (“FHWA”) on the number of driver’s licenses issued by the state’s DMV and data reported biennially to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (“EAC”) about the number of voter registration applications submitted through the DMV, we calculate the ratio of DMV voter registration applications to driver’s licenses issued to produce a rough approximation of the proportion of driver’s license transactions during which an individual submits a voter registration application. Using that ratio, we grouped the states into three performance groups (“Motor Voter Groups”) based on their rate of generating voter registration applications during DMV transactions.

A state’s Motor Voter Group provides an approximate measure of the state’s performance in registering voters who come to the DMV to transact business related to their driver’s licenses. Assigning states to Motor Voter Groups is a preliminary step intended to inform and be informed by further factual research and investigation into states’ compliance with Section 5. In our subsequent analysis, we use the Motor Voter Groups to evaluate the effectiveness of the differing procedures used by the states to implement Section 5 of the NVRA in facilitating voter registration through DMVs. In addition, we use the Motor Voter Groups to calculate the potential increase in the number of voter registration applications that would be submitted through DMVs if states increased their DMV voter registration rates by adopting more effective procedures and improving their compliance with Section 5.

A. An Assessment of Motor Voter Performance in the States

Registering to vote through motor vehicle agencies under Section 5 of the NVRA is supposed to be a relatively simple, straightforward process. Relying on the fact that a large proportion of eligible voters are also driver’s license holders, the NVRA’s drafters envisioned voter registration at the DMV as one of the primary ways eligible citizens would access voter registration. As a result, our starting assumption is that states in compliance with Section 5 will ‘convert’ a relatively high proportion of DMV transactions into voter registration applications.

With this assumption in mind, we take a two-step approach to the data analysis of voter registration through DMVs. We start with two related assessments of voter registration activity using the data states report to the FHWA and EAC and then conduct follow-up analyses to gauge the impact of several of the limitations we identified in the data. This analysis raises significant concerns regarding the state of compliance with Section 5 in many states. Significantly, a number of DMVs appear to be registering very few voters as compared to the number of driver’s license and ID card transactions they conduct. Improving states’ performance in registering voters through their DMVs has the potential to add a large number of eligible voters to the voter rolls.

1. Comparisons of DMV Voter Registrations to DMV Transactions

In the first assessment of voter registration activity, we approximated the level of voter registration activity at each state’s DMV by calculating the ratio of DMV voter registrations as reported to the EAC for the 2011-2012 election cycle to the number of DMV licensing transactions conducted by each state, as reported to the FHWA during roughly the same time period (“DMV voter registration ratio”). As shown in Figure 1, the level of voter registration activity at DMVs varies widely among states, ranging from approximately one voter registration application for every two licenses issued at the high end to one voter registration application for every 83 licenses issued at the bottom. The wide variation in generating voter registration applications during driver’s license transactions suggests that in some states, voter registration has been effectively integrated into drivers’ license transactions in compliance with the NVRA, while in other states, it has not.

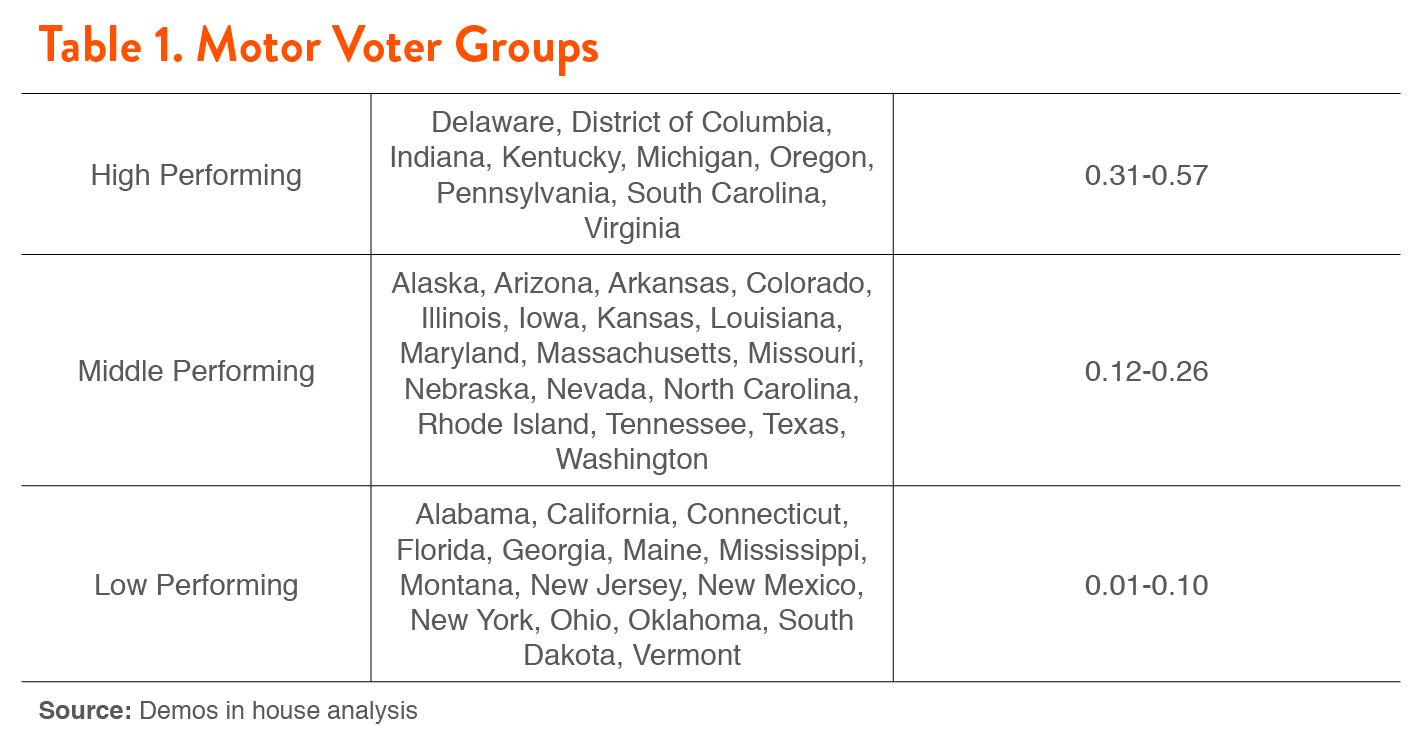

Using the DMV voter registration ratio, we grouped the states into Motor Voter Groups in the 2011 to 2012 time period. States in the highest group reported receiving three or more voter registration applications through the DMV for every ten DMV transactions while states in the lowest performing group reported just one or fewer voter registration applications for every ten DMV transactions (see Table 1). The states in the lowest performing Motor Voter Group, and many of the states in the middle performing Motor Voter Group raise concerns that they may be out of compliance with Section 5 of the NVRA and, thus, may be good targets for further investigation. Conversely, states in the high Motor Voter Group may bear further analysis as a means of identifying particularly effective Motor Voter implementation mechanisms.

2. Comparison of DMV Voter Registration Activity to Overall Voter Registration Rates

It is possible that a low DMV voter registration rate might be explained, at least in part, by a high overall rate of voter registration in a state. In other words, low proportions of voter registration applications through the DMVs of particular states could simply reflect the fact that larger proportions of the citizens in those states are already registered to vote and fewer are therefore unregistered when they visit the DMV. Conversely, a high rate of DMV voter registrations might reflect the fact that many voters in the state are unregistered when they transact business with the DMV. In the second assessment of voter registration activity, we explore this possible explanation for the observed variances by comparing the DMV voter registration ratio (computed in the first data assessment) with overall voter registration rates.

A simple plot of DMV voter registration ratios against overall registration rates shows that in many cases, low DMV registration ratios cannot be explained by a high rate of voter registration in the state (see Figure 2). For example, a state with one of the lowest ratios of DMV voter registrations to DMV transactions—California—also has among the lowest over all voter registration rates at about 65 percent of eligible voters. Moreover, even in states with high overall registration rates, a low DMV voter registration ration may be the result of NVRA non-compliance. Determining whether there is a relationship between the DMV voter registration ratio and statewide voter registration rate in any particularly state would require consideration of numerous factors—such as the availability and effectiveness of alternative methods of voter registration, non-citizen driving population, and political competitiveness, among others—and such an analysis is beyond the scope of this study. Accordingly, we have examined Section 5 compliance in every state covered by the NVRA regardless of its statewide voter registration rate.

Nevertheless, the plot shown in Figure 2 demonstrates that there are a number states with both low levels of DMV voter registration activity and low overall voter registration rates. These states present particular concerns and may have the most potential for significant impact through improved Section 5 compliance. Because they have low overall registration rates, there may be room to increase these states’ registration numbers. Because they currently register relatively few voters through motor vehicle agencies, they may have Section 5 compliance issues that more effective voter registration procedures could help address.

We identified some specific cases in which states have both very low rates of DMV voter registration and low overall registration rates. Thirty-five percent of eligible Californians, 31 percent of eligible Connecticuters and 32 percent of eligible New Mexicans are not registered to vote. All three states were in the low performing Motor Voter Group in 2011-2012 (in fact they were three of the bottom four states by DMV voter registration ratio). Also, both of the states that failed to report some of the data required for our 2011-2012 analysis—Hawaii and West Virginia—have low overall voter registration rates. Forty-four percent of eligible voters in Hawaii and 32 percent of eligible West Virginians were not registered to vote in 2011-2012. Based on this particular analysis, these states’ compliance with Section 5 likely merits additional scrutiny.

B. The Potential of More Effective Motor Voter Implementation

To get a sense of the potential impact on voter registration of better implementation of Motor Voter, we calculated the number of additional voter registration applications DMVs might receive with more effective DMV voter registration programs. We started by calculating the total number of voter registration applications DMVs would have received in each state in the two lower Motor Voter Groups if their DMVs had generated voter registration applications at the same rate as the high Motor Voter Group. In other words, we calculated the number of voter registrations these DMVs would have generated had they generated three registrations for every ten licensing transactions, the threshold for inclusion in the high Motor Voter Group. Then, we subtracted the number of DMV voter registrations each state actually reported in 2011-2012 from these numbers to calculate the number of additional DMV voter registration applications that could be achieved nationwide if states increased their performance to this level.

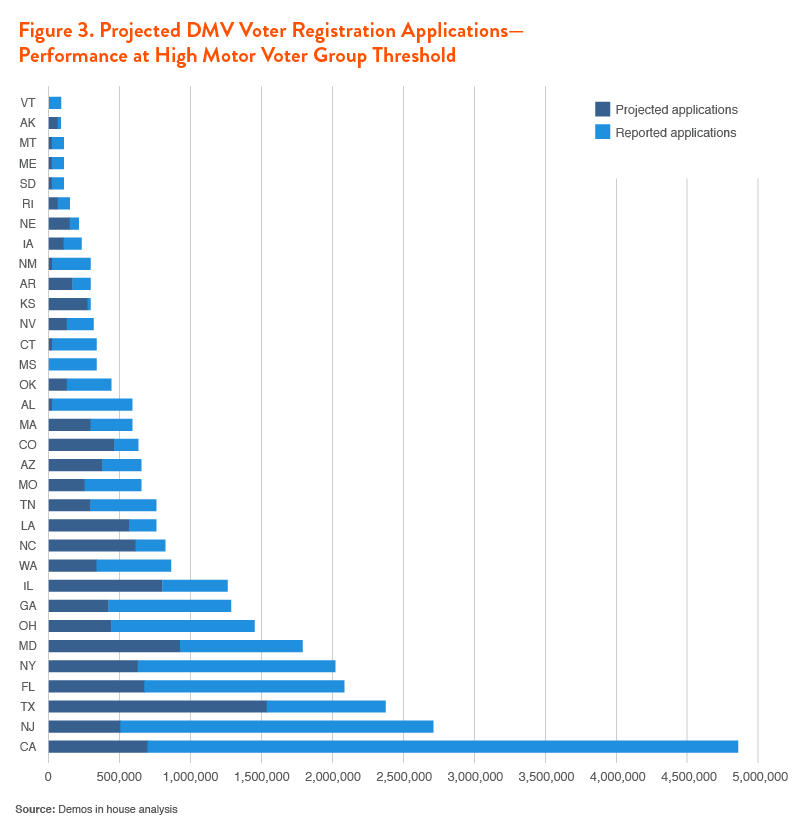

Bringing all states in the low and middle performing Motor Voter Groups up to the 0.30 minimum level for them to qualify for the high Motor Voter Group would more than double the number of voter registration applications originating at DMVs in those states. As illustrated in Figure 3, if the states currently ranked in the low and middle Motor Voter Groups had generated just three voter registration applications for every ten covered DMV transactions that occurred during the 2011-2012 election, 18.4 million additional DMV voter registration applications would have been generated nationwide in that two year period.

III. State Procedures For Implementing Motor Voter

To explore the reasons for the wide variation in DMV voter registration rates and to gain insight into how poor-performing states might improve, Demos conducted extensive legal and factual research into states’ implementation of Section 5. This research consisted of three component parts: legal research; review of public records, including DMV forms, readily accessible and publicly available information, and information produced in response to public records requests; and field investigations in two states. The goal of this research was to gain an understanding of how voter registration is being offered during covered driver’s license transactions, to assess the compliance with the NVRA of state implementing practices and procedures, and to evaluate the effectiveness of those practices and procedures in increasing the number of driver’s license transactions that result in a voter registration.

A. Statutory Requirements

To provide a framework for understanding state compliance with Section 5, we must first understand what the statute requires. Section 5, entitled “Simultaneous application for voter registration and application for motor vehicle driver’s license,” establishes voter registration at and by state motor vehicles departments. 52 U.S.C. § 20504. Section 5 describes the voter registration services that must be offered by DMVs during various client interactions, and includes specific requirements concerning the form and content of the voter registration elements of the driver’s license or ID card application, renewal, and change of address forms.

Stated succinctly, with respect to the requirement for simultaneous voter registration and license application or renewal, the best interpretation of the NVRA requires a state (1) to provide a single application form or process that serves both to apply for a driver’s license and to register the applicant to vote, or (2) to provide the driver’s license application or renewal and the voter registration application on separate application forms that are distributed to the applicant simultaneously as part of the same application packet. Id. § 20504(a)(1), (c)(1). Under either interpretation, the applicant may not be required to provide duplicative information in order to register to vote, i.e., information that must also be provided on the driver’s license application. Id. § 20504(c)(2). If an applicant is already registered to vote, the driver’s license application or renewal form must update the existing voter registration. Id. § 20504(a)(2).

With respect to changes of address, the DMV is required to notify elections officials of any driver’s license change of address information unless the voter affirmatively indicates that the address change is not to be applied to her voter registration record. Id. § 20504(d). There is no doubt that, upon receiving a change of address notification from the DMV, a local voter registrar must update a voter’s registration record for any address change within the registrar’s jurisdiction. Id. §§ 20504(d), 20507(f). The best interpretation of the statutory language requires the registrar to update the registration records upon receiving a notification of a change of address regardless of whether the change is within a jurisdiction or to a new jurisdiction. In addition, Section 5 may also require DMVs to offer an individual conducting an address change who is not already registered to vote at her new address the same opportunity to register to vote as is offered with the initial driver’s license application.

Voter registration applications received by a DMV are considered submitted, for purposes of a state’s voter registration deadline, as of the date they are submitted to the DMV. Id. § 20507(a)(1)(A). The DMV must transmit completed voter registration applications to the appropriate election officials within 10 days from the time they are received. Id. § 20504(e)(1). If the application is accepted within 5 days of the voter registration deadline, the DMV must transmit it to the appropriate election official within 5 days of acceptance. Id. § 20504(e)(2).

B. Varieties of State Practice

Section 5 sets forth the general requirements for voter registration at DMVs, but it allows states a certain amount of flexibility to implement those requirements in ways that integrate most effectively into their existing DMV and voter registration systems. Accordingly, in their local implementation of Section 5’s commands, states have adopted a wide variety of laws, regulations, procedures, and practices. Unfortunately, many states are providing voter registration through their DMVs in ways that appear blatantly inconsistent with the requirements of Section 5, while other states have adopted procedures that may satisfy the letter of the law but are ineffective in achieving its purposes.

A number of conclusions can be drawn when the practices that are common across a number of states are compared to those states’ performance in registering voters through the DMV, as determined by the Motor Voter Group. In states that are more successful in registering voters during licensing transactions, we observed a range of DMV procedures that serve to reduce barriers to registration experienced by voters and others that increase the efficiency and accuracy of the communications between the DMV and elections officials. In contrast, it appears that the procedures in use in states with lower DMV voter registration rates fail to satisfy their obligations under Section 5. Many DMVs, particularly those falling in the lowest Motor Voter Group, operate under policies and procedures that, rather than establishing a streamlined voter-registration process, place unnecessary barriers in the way of voter registration for driver’s license applicants, contrary to the letter, spirit, and purpose of the NVRA.

The voter registration procedures used in DMVs across the spectrum fall into six broad categories. As summarized below and described in more detail in Appendix C, in each of these categories, we observed individual practices or procedures that appeared effective in encouraging driver’s license applicants to register to vote and others that were not only ineffective but appear to violate the requirements of Section 5.

- Integration of voter registration into the driver’s license application. The states achieving the greatest success in registering voters through DMVs actively engage voters and ensure that they cannot overlook the voter registration option. These states offer voter registration during an oral interaction with a DMV employee or by using computer terminals that walk the voter through the voter registration process. Many states achieving low to moderate success in registering voters integrate voter registration into their driver’s license services in a more passive way, typically by incorporating a voter registration application directly into their driver’s license application and renewal forms. The worst performing states fail to effectively integrate voter registration into the driver’s license application process at all. These DMVs typically offer a separate, usually blank, voter registration application only to those who request it; many also require voters to submit their applications to election officials rather than accepting and transmitting them themselves.

- Implementation of the prohibition on requiring duplicate information. The states that are most successfully registering voters through the DMV have generally taken a robust approach to ensuring their DMV voter registration process does not require voters to provide information that is duplicative of information required for the driver’s license transaction. Some states achieve this by providing voters with a voter registration application that is pre-filled with the voter’s name, address, and other information provided on the driver’s license application. Others treat the driver’s license application itself as a voter registration application if the voter indicates a desire to register (either by checking a box, signing a voter registration affirmation, and/or responding to an oral inquiry). A large number of states violate Section 5’s no duplication requirement, either by requiring voters to fill out a separate, blank voter registration application or, in states using a combined form, by failing to carry over some or all of the information required for the driver’s license application to the voter registration section of the application form.

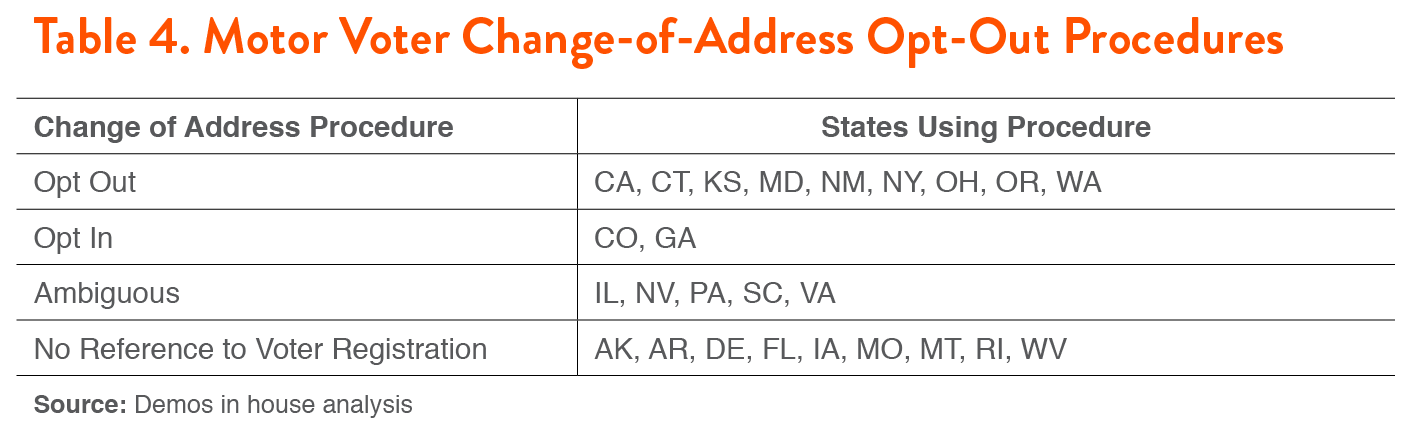

- Address updates with the possibility for voters to opt out. Section 5 requires states to update a voter’s voter registration address when the voter submits a driver’s license address change unless the voter indicates that the change is not for voter registration purposes. Many states implement this requirement by treating a driver’s license change-of-address notification as a voter registration change-of-address notification and providing the voter an opportunity to opt out of the voter registration update. Some states, however, require the voter to affirmatively indicate that the voter registration address should be updated—an opt-in rather than opt-out system—which can lead to voters being inadvertently dropped from the roles.

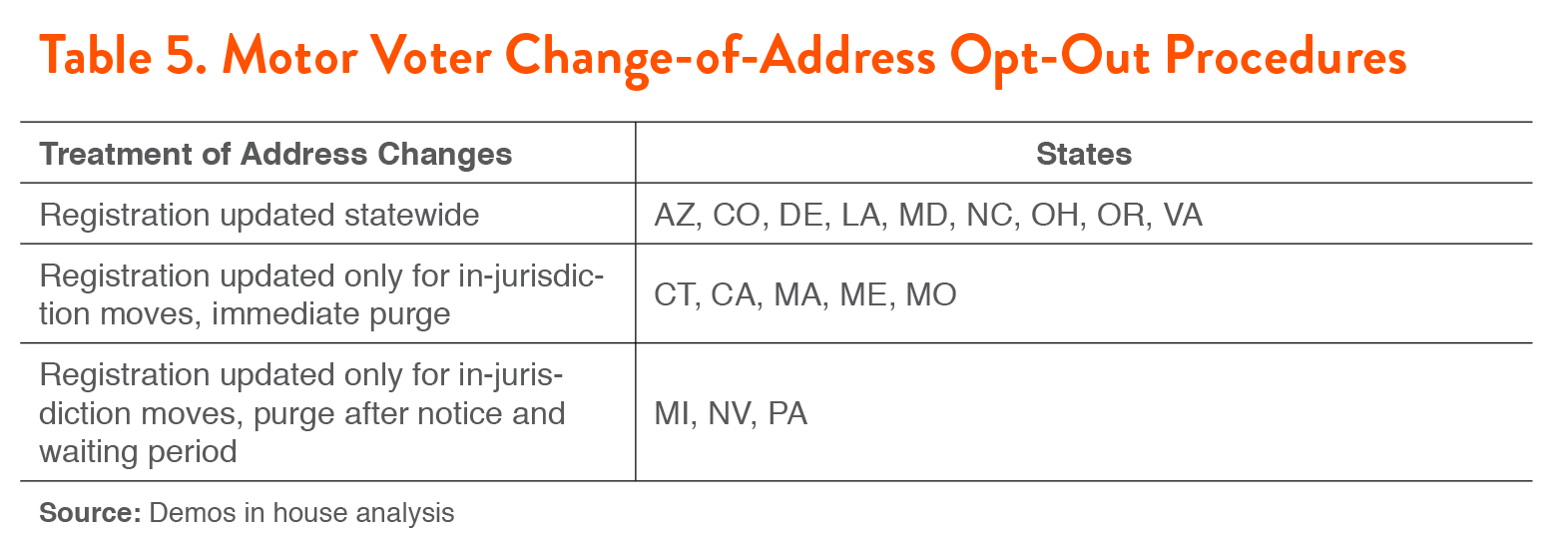

- Handling of address-change notifications. There are three primary ways states handle driver’s license change-of-address notifications submitted to the DMV. First, some states offer voters the opportunity to register if they are not already registered or to update their address if they are registered. Second, some states update the voter registration address for voters who are already registered, but do not offer voter registration to unregistered voters during change-of-address transactions. Third, some states update the voter registration address for voters who move within a single voter registrar’s jurisdiction (typically, a county), but not for voters who move from one jurisdiction to another. Voters who move to a new registrar’s jurisdiction are removed from the voter rolls and must re-register to vote. Worse, many of these states do not adequately notify voters of the need to re-register and do not offer the opportunity to register through the DMV.

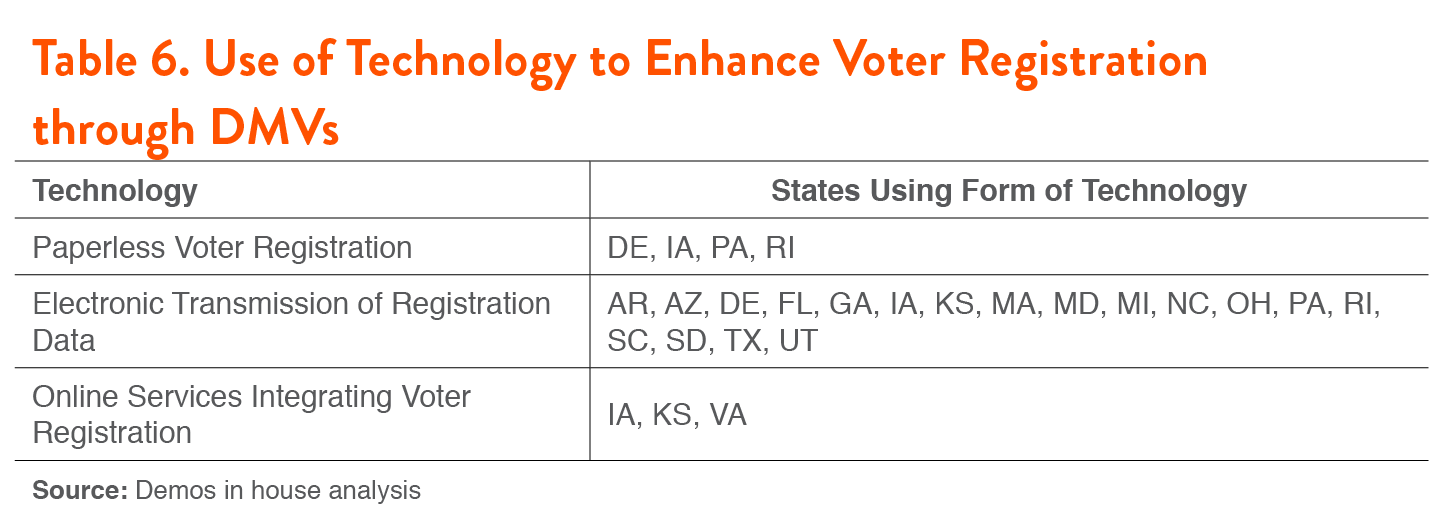

- Use of technology. States use technology to implement voter registration in two primary ways. First, technology can be used to integrate voter registration into the driver’s license transaction, for example through an electronic or online registration system. Second, technology can be used to transmit voter registration information from the DMV to elections officials. The states that are most successful in registering voters use technology in one or both of these ways. The states with lower DMV registration rates typically do not leverage technology effectively or at all to enhance their DMV voter registration efforts, even when existing technology offers opportunities to do so.

- Voter registration assistance. States offer varying levels of assistance in completing the voter registration application to those who need it. This assistance can take many forms, from language assistance to explaining eligibility requirements to simply ensuring voters are aware of the opportunity to register. States that offer voter registration assistance at DMVs, and especially states that make access to assistance a seamless part of completing the application, tend to achieve higher rates of voter registration in relation to the number of DMV transactions they conduct.

C. Case Studies

No state’s success in implementing Motor Voter is determined by a single practice or policy. In this part of the report, we drill down on selected states, examining how the constellations of practices and procedures they employ affect their effectiveness in registering voters through their DMVs. These states were selected either because they appear to be particularly successful in registering voters at their motor vehicles departments or because they appear to have adopted one or more policies that are facially non-compliant with Section 5 and to be performing poorly in registering voters through their DMVs.

1. Robust Integration of Voter Registration: Michigan

Michigan’s implementation of Section 5 of the NVRA is distinctive in at least two key ways. First, the Secretary of State is responsible for both elections and licensing drivers. Second, Michigan requires voters to use the same residence address for both driver’s license and voter registration. Together, these features of Michigan law have allowed Michigan to implement a system of streamlined registration that is effectively permanent, at least for voters who hold a driver’s license or state ID card.

Michigan’s driver’s license application does not integrate a voter registration application into the driver’s license application form itself, but the information needed to determine eligibility is required for the driver’s license application, and during the driver’s license transaction, a voter registration form preprinted with the information from the driver’s license application is automatically generated. In addition, Michigan’s motor vehicles offices electronically transfer voter registration data to elections officials, and where the voter’s signature is on file, the registration will be processed even if the paper application is not received.

Changes of address submitted to the DMV in Michigan will update the voter’s registered address regardless of whether the move is within a single jurisdiction. Elections officials will process the address change even if the voter fails to sign the form if the voter’s signature is already on file. Moreover, Michigan is one of a small number of states that offers initial voter registration during change of address transactions for voters who are not already registered as well as statewide updates for those who are. Unlike the initial driver’s license application form, the change of address form does integrate a voter registration application.

These motor vehicle voter registration procedures are indicative of a state that has made an effort to make voter registration and updates as easy as possible for the voter and for the officials responsible for voter registration and driver’s licenses. The success Michigan has achieved at registering voters through its motor vehicles department bear out this assessment. Among all states, Michigan has the highest DMV voter registration rate.

2. Effective Use of Technology: Delaware

Delaware has expended considerable resources to replace its paper-based DMV voter registration system with an electronic system built on a tight integration between its motor vehicle and elections information systems. The result is a streamlined voter registration process that ensures voters who interact with the DMV can register and remain registered when they move. Using this system, a voter engaging in a DMV transaction registers to vote through an electronic terminal, which also captures the voter’s signature. The voter registration application is transmitted directly to the elections department where the voter’s eligibility is verified through integration with federal social security and immigration databases.

Delaware’s investment in its DMV voter registration infrastructure has yielded a streamlined process for voters and efficient administration for DMV and elections officials. Most significantly, it has paid off in the large number of Delaware voters who register through the DMV.

3. Separate Voter Registration Application Requiring Duplication: California

California ranks in the bottom Motor Voter Group and uses a number of practices that appear to violate the NVRA. First, it does not integrate voter registration into its driver’s license application. While it has a question on the application form asking whether the applicant wishes to register, the applicant must complete a separate voter registration application. California’s NVRA Manual requires the DMV to provide a voter registration application with every driver’s license application, but it does not pre-populate it with any of the information the voter provided when applying for the driver’s license.

California’s driver’s license change of address form contains a check box by which a voter can indicate that the change should not be applied to the voter registration record, which in itself is compliant with Section 5. California does not perform automatic updates of addresses within its voter registration system for all voters, however. Voters who have moved from one county to another have their voter registration records cancelled and, as noted on the driver’s license application and change of address forms, must submit a new voter registration application to remain eligible to vote.

Our field investigation largely confirmed what our research had suggested about California’s process. Voters are given a blank voter registration application when they request a driver’s license application. With respect to changes of address, our field investigation revealed that, contrary to the state’s policy as stated in its NVRA Manual, voters—including those moving from one county to another, who are required to reregister—are not given even a blank voter registration application. Officials at several different DMV offices told us that during change of address transactions, voter registration applications are provided only if the applicant requests one, and this was confirmed by client interviews. In one office, a wall slot offering voter registration applications was accompanied by a notice that voters must reregister when moving to a new county, but it contained no voter registration applications.

The field investigation also provided confirmation of what we expected the effect of California’s practices to be: Most individuals applying for a driver’s license did not complete the voter registration application while at the DMV, even when they responded “yes” to the voter registration question on the driver’s license application form.

4. No Integration, Duplication, and Confusing Forms: Nevada

Nevada, the second state where we conducted field surveys, is an example of a state that falls in the middle Motor Voter Group and raises compliance concerns. Like California, Nevada does not integrate voter registration into its driver’s license application process, instead offering voters a blank voter registration application that must be separately completed and submitted, and it does not update voter registration records for voters moving between counties, but requires them to reregister. Unlike California, however, Nevada’s state law requires elections officials to use DMV changes of address to “correct” existing voter registration records without regard to whether the move was within a county or to a new county.

Where Nevada differs from California, its procedures create even more barriers to registering to vote at its DMVs. First, it does not provide the blank voter registration forms as part of the driver’s license application or change of address packets, but gives them only to voters who request the opportunity to register. Second, the design of its driver’s license application form is highly confusing and creates a high likelihood that voters will not see the check box by which they can request a voter registration application. The first page of the driver’s license application contains a series of questions concerning updates to the voter registration database for voters who are reporting a new address, but does not ask applicants whether they wish to register to vote. A separate question, printed in small type and buried on the second page of the form in a list of questions concerning veteran status and organ donation, asks whether the applicant wishes to register to vote. It appears that only applicants who check this second box are offered a voter registration application.

Our field investigation in Nevada provided evidence that the design of the driver’s license application form is indeed negatively impacting the number of individuals who register to vote during licensing transactions. Approximately 40% of the individuals we interviewed who had visited the DMV to apply for or renew a driver’s license had not noticed the question asking whether they wanted to register to vote. In addition, the field investigation revealed that many individuals who saw the question and indicated that they wished to register were not offered a voter registration application, in apparent violation of the DMV’s stated policy, indicating that the form’s design may be confusing for DMV employees as well as voters.

Importantly, the field investigation provided evidence that having DMV staff orally offer voter registration increases the number of driver’s license applicants who chose to register—perhaps partially explaining Nevada’s presence in the middle performing Motor Voter Group rather than the low performing Motor Voter Group. Of the voters who saw the question on the driver’s license application offering voter registration, only about one in fifteen checked “yes,” while of the voters who were orally offered a voter registration application, one in five chose to receive it.

IV. Improving Voter Registration at DMVs

Based on the above analysis as well as the successes and failures of individual states that have adopted specific sets of practices and procedures in their implementation of Section 5, we can begin to identify a set of model procedures that states might adopt to increase the effectiveness of their DMV voter registration efforts. In this Part, we set forth two sets of model procedures. One set recommends several steps states can take to increase DMV voter registration applications regardless of the level of technology they have available. The second set of model procedures is adapted to states that already have implemented or have the resources to implement a robust integration of their DMV and elections information systems. These states have a number of options for offering voter registration at DMVs that may be unavailable to states with fewer technology resources.

A. Model Procedures for Improving DMV Registration Regardless of a State’s Technology

In all states, including those with lower levels of existing technology and fewer resources to implement new technology, a number of steps can be taken that have the potential to dramatically increase voter registration at DMVs. Where it exists, technology can be leveraged both to increase the effectiveness of these steps and to reduce their cost even further. We recognize that some of these suggestions might require legislative action at the state level, but where the political will exists, the monetary costs are not high. Moreover, most if not all of these steps are mandated by the NVRA, and states that fail to adopt them may be subject to enforcement action by private parties or the U.S. Department of Justice, which also can result in substantial costs for the state.

First, we recommend that states adopt a driver’s license application and renewal process that seamlessly integrates voter registration through an active offer of voter registration services and that does not require duplication of information. Actively prompting voters to take the opportunity to register to vote during a driver’s license transaction appears to have a greater impact on the number of voter registration applications submitted through the DMV than more passive forms of integrating voter registration, including the use of a fully integrated driver’s license application and voter registration form. Indeed, states that combine an oral offer of voter registration with the use of a separate voter registration form that is pre-filled with the information provided on the driver’s license application tend to outperform those that use an integrated form with no active prompt regarding voter registration. Several of states in the high-performing Motor Voter Group integrate voter registration into the driver’s license application process in a way that ensures voters are aware of the opportunity to register to vote and must make an affirmative decision whether or not to avail themselves of it.

Second, we recommend that states offer initial voter registration for individuals changing their address with the DMV, if the individual is not already registered. In most states, address changes are likely the most frequent interaction voters have with the DMV (the exception being those with very short driver’s license renewal periods). In addition, in states that do not have pre-registration of 16- and 17-year-olds, an address change may be the voter’s first interaction with the DMV after becoming eligible to vote. Providing voter registration during address changes can have a dramatic impact on DMV voter registration rates and has the potential to bring many more people into the political process.

Third, we recommend that when voters submit a change of address to the DMV, the state should automatically update the voter registration address regardless of whether the new address is within or outside the jurisdiction of the voter’s previous residence unless the voter affirmatively indicates that the change is not for voter registration purposes. Even low technology states have implemented statewide voter registration databases, which should make it possible for voter registration records to be transferred between jurisdictions with little to no additional investment. States with robust links between DMV and elections databases can perform paperless updates. Statewide address updates decrease the likelihood that a voter who is already registered in one jurisdiction will have a second voter registration record created in another jurisdiction, thus reducing the number of duplicate or stale voter registration records and lowering list maintenance costs. More importantly, automatically updating a voter’s address whenever and wherever she moves helps ensure that once a voter is registered, she stays registered.

Finally, we recommend that states offer assistance to voters in completing the voter registration application. Providing assistance does require some investment in employee training, but because it has the potential to speed up the voter registration component of the licensing transaction, it need not add significant time to the overall transaction and may even reduce it in many cases. In addition, because assistance is already required of public assistance agencies, many states will already have training materials available that can be adapted to the DMV context.

All of these steps offer low-technology mechanisms for raising the number of voters who choose to register at the DMV and for increasing participation in our nation’s democratic process.

B. Model Procedures that Leverage Technology Infrastructure

Technology can improve the voter registration process at DMVs in two key areas: interaction with voters and linkages between agencies.

With regard to how voters interact with the DMV around voter registration, based on our review of practices across states and the experience of Delaware and Pennsylvania in particular, we recommend that states adopt electronic voter registration systems for use within the DMV. Delaware currently uses a special purpose electronic pad for voter registration. Pennsylvania has a customer computer terminal at the same counter where applicants appear to apply for a driver’s license, allowing the applicant to complete the voter registration process through the same computer system the DMV uses to enter driver’s license application data. Many other alternatives are available that make use of off-the-shelf technology. Model electronic registration systems include the following features:

- Require the voter to answer a question whether or not to register, ensuring that voters are aware of the opportunity to register and allowing for better monitoring of NVRA compliance and DMV voter registration performance; and

- Walk the applicant through the voter registration process step-by-step, as is done in both Delaware and Pennsylvania. Breaking the application down into discrete questions further simplifies the registration process for voters and allows for targeted assistance to be provided at specific points in the application. In Pennsylvania, for instance, internal instructions specify the type of assistance that may be offered at each stage: For example, at the party selection stage, the DMV employee may explain how a voter can select a party that does not appear in the list, but may not attempt to influence which party is selected;

- Capture the voter’s signature electronically through a signature pad or other device. When combined with electronic transfer of voter registration data as described below, electronic signature capture allows states to move to an entirely paperless registration system.

In addition, we recommend that states integrate voter registration into any driver’s license services they offer online via the Internet. Many states allow licenses to be renewed online and most offer the ability to update an address online. Unfortunately, most of these online systems were not designed with voter registration in mind. In states with online voter registration, implementing registration within online DMV services can often be done at relatively low cost.

On the back end, we recommend that states establish an electronic linkage between DMV to elections information systems, and provide for electronic transfer of voter registration data from the DMV to elections officials. Since the passage of HAVA, nearly every state has implemented a statewide voter registration database, which significantly simplifies the effort required to establish such a linkage. Where possible, we recommend that states move to a paperless system of voter registration through DMVs. When voter registration applications are transferred entirely electronically, the possibility of lost applications or inaccurate entry of voter registration data is reduced, while the ability to audit DMV voter registration activities is improved. Moreover, shifting voter registration away from paper should result in significant cost savings over time.

Integration of DMV and elections information systems requires an up-front investment of effort and money. Many states, however, already have significant infrastructure in place that is simply not used. For example, states that have online registration systems typically already have some mechanism to a) verify the voter’s identity, residence, and eligibility via an electronic link to the DMV database, and b) transfer an electronic image of the voter’s signature from the DMV, where it may have been scanned from the driver’s license application or captured on an electronic signature pad, to the elections department. Relying on these features of online registration, a paperless voter registration system can be built at the DMV on existing technology. Many online voter registration systems also already offer the ability to track the source of the voter registration, assisting elections officials in their NVRA monitoring and reporting obligations. Often, these states simply need to muster the will to do a limited amount of additional integration work to provide for seamless registration of voters during DMV transactions.

V. Conclusion

Twenty years after the enactment of the NVRA, many states are failing to offer meaningful opportunities for individuals to register to vote during motor vehicles department transactions. To realize the NVRA’s promise of “enhanc[ing] the participation of eligible citizens as voters,” states must take seriously Section 5’s mandate to make registering to vote an integral part of obtaining, renewing, or updating a driver’s license or state identification card. The states that are most successfully implementing Motor Voter provide evidence that by adopting cost-effective, commonsense procedures and relying on existing technology and infrastructure, this goal is attainable. When states achieve full compliance with Section 5, millions more Americans will have the opportunity to participate in our democracy.

Appendix A: Data Analysis Methodology

Appendix A describes the methodology Demos used to collect and analyze the voter registration and driver’s license data used in this report, various limitations encountered in the data, and the measures taken to compensate for those limitations.

A. Data Used

Data on the number of driver’s licenses and non-driver ID cards issued (DMV transactions) was collected from individual state reports electronically submitted to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) in 2011 and 2012 on Form FHWA-562. These reports were provided to Demos in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the FHWA.

Data on the number of voter registration applications received by motor vehicle agencies (DMV voter registrations) was collected from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s (EAC) 2011-2012 National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) Study.

Most data on the number of registered voters was collected from the 2012 U.S. Census’ Current Population Survey. Additional data was collected from state elections websites, as necessary.

Data on the voting eligible population (VEP) was collected from the United States Elections Project’s 2012 VEP estimates. The U.S. Elections Project, which is maintained by Michael McDonald of the University of Florida, combines data on the number of voting age residents with data on the number of non-citizens, ineligible residents with felony convictions and eligible overseas voters to estimate the number of residents in each state who are eligible to vote.

B. Limitations of the Data

There are a number of limitations to the data reported by the states to the EAC and FHWA. These limitations fall into four main categories:

- Selected missing values: Some states failed to report some or all of the data required to calculate their DMV voter registration rates in one or more of the years examined.

- General missing values: Some of the data required for a full calculation and comparison of DMV voter registration rates, such as the number of changes of address processed by DMVs, the number of DMV transactions involving members of groups that are ineligible to register to vote (e.g. non-citizens, individuals under the age of 18 in many states, individuals with felony convictions in many states, etc.) and the number of DMV visitors who knowingly decline the opportunity to register to vote, is not systematically collected by the relevant federal agency.

- Non-overlapping timeframes: The EAC and FHWA have different reporting timelines so the data reported by states to the EAC covers a different timeframe than the data they report to the FHWA.

- Inconsistencies across or within states: As researchers working with the Pew Charitable Trusts have noted, states sometimes collect data or interpret federal survey questions differently. As a result, the data they provide in response to the same survey questions do not always capture the same set of data. The same state may also provide inconsistent information in response to different requests or in different reporting periods, as was the case with at least one state Demos contacted.

C. Follow-Up Analysis

We took a three-part approach to addressing these limitations. First, where there was a known issue with the data and enough other data to attempt to compensate for the issue, we attempted to compensate for it. We extrapolated missing values where possible, corrected for variations in states’ interpretations of survey questions where they were made explicit, and prorated data to estimate conversion rates for overlapping EAC and FHWA timeframes and DMV transactions involving only voting eligible populations. When we recalculated the affected states’ conversion rates using extrapolated and estimated data, our results were not substantially different from the results we obtained using the original data.

Second, where there was a known issue with the data but not enough other data to attempt to compensate for it, we removed the affected state(s) from the comparisons. For example, where states failed to report some or all of the data required to calculate their DMV voter registration rates for one or more years and we could not extrapolate the missing data from other reported data, we removed the states from the analysis. We also removed Utah from the assessments because based on the data it reported to the EAC, it was a significant outlier, and because the data it reported to the EAC was significantly different from the data its motor vehicles department provided in response to a public records request from Demos and there was no clear way to determine which set of data was more accurate.

Third, to account for unknown issues with the data, such as unreported inconsistencies in the way states interpreted and responded to federal survey questions, we narrowed our use of the data as much as possible. In the report as a whole, we put the conversion rate data to two main purposes:

- Identifying best practices for DMV voter registration

- Identifying targets for further legal and field research

To minimize issues with the first of the above uses, we used states that have been identified as good data collection states as our benchmarks whenever possible. Two of the states with the highest reported conversion rates—Delaware and Michigan—have been identified by the Pew Charitable Trusts as states with fairly complete DMV registration data reporting. Therefore, we can have some confidence that their relatively high reported conversion rates reflect their actual performance and that they are good sources of best practices for DMV voter registration.

Using the data for the second purpose is relatively unproblematic, even with unreported and unaddressed reporting inaccuracies. There are three ways in which the data states report could relate to their actual performance: it could accurately reflect performance, overstate performance, or understate performance. If the data for a state in the low DMV voter registration rate group falls in either the first or second of these categories, its performance is as low or even lower than it appears. In either of these circumstances, the state is converting few DMV transactions into voter registration applications and is a good target for further investigation.

If the data for the state falls in the third category and the underestimate is insignificant, the state is in essentially the same situation as if it fell in the first or second category. If the underestimate is significant, there is a serious data reporting problem in the state that merits attention. Further investigation will be necessary to identify such states and could help identify and address the reporting problems, which would ultimately help produce more accurate data on and benchmarks for Section 5 activity.

Appendix B: Legal Research Methodology

To explore the reasons for the wide variation in voter registration rates at motor vehicles departments (“DMVs”) that we found in our analysis of DMV transaction and voter registration data and to gain insight into how poor-performing states might improve, Demos conducted extensive legal and factual research into the implementation of Section 5 of the National Voter Registration Act (“NVRA” or the “Act”) by each state covered by the Act, as described in this Appendix. The goal of this research was to gain an understanding of how voter registration is being offered during covered driver’s license transactions. This research consisted of three component parts: legal research; review of public records, including DMV forms, readily accessible and publicly available information, and information produced in response to public records requests; and field investigations in two states.

In several states, however, even after conducting exhaustive research, we were unable to determine with any confidence exactly how voter registration is being offered at DMVs during covered driver’s license transactions. In many of these cases, state statutes merely mimic the NVRA and provide no insight into the detailed procedures used to implement, and state administrative regulations are similarly general if they exist at all. In response to public records requests, these states provided little information if they have responded at all, and what they provided was of limited usefulness to increase our understanding of their procedures. Where we could not determine a states practices and procedures with sufficient confidence, we excluded those states from most of our analysis. With respect to most states, however, we have a clear, if not perfect, sense of the steps they are taking to comply with Section 5.

A. Legal Research

For each state covered by the NVRA, we reviewed the state statutes that were passed to implement Section 5. These statutes provide the starting point of state efforts to offer voter registration at DMVs. They typically identify the relevant state agencies and officials and enact into state law those agencies’ obligations under Section 5. In some cases, these statutes set out the obligations in considerable detail, specifying with a high degree of precision the form and content of the DMV documents that must incorporate voter registration. In addition, we examined ancillary laws that might impact voter registration at the DMV, such as laws setting voter eligibility requirements, laws that impact the frequency with which voters interact with the DMV, laws providing for preregistration of 16 and 17 year olds, laws concerning how election officials process updates to voter information, and, where they exist, laws requiring voters to show identification at the polls.

After analyzing the implementing statute, we researched whether the DMV or the state elections department had adopted administrative regulations pertaining to voter registration at the DMV. Many states use administrative regulations to fill out the general obligations of their implementing statute at a more concrete level and to set policy concerning voter registration at the DMV. For example, the regulations may specify the responsibilities of individual officers or set the terms of access to the statewide voter registration database or command coordination between agencies on voter registration.

B. Review of Public Records

Statutes and regulations do not always provide insight into how a statutory command is put into practice. We therefore reviewed publicly available information concerning registering to vote during driver’s license transactions, and we set public records requests to DMVs seeking additional information, which we then reviewed. The records requested and the information reviewed included driver’s license application, renewal, and change of address forms; information DMVs provide to the public concerning voter registration, including material available on DMV websites; more detailed statistical data concerning voter registration and DMV transactions than was available from public sources; documents reflecting policies and procedures governing voter registration at DMVs; and information concerning the incorporation of voter registration into online driver’s license transactions. These public records allowed us to gain a fuller understanding of how voter registration is offered in DMVs throughout the country.

C. Field Investigations

In two states—California and Nevada—we supplemented our legal research and review of public records with field investigations at state DMVs. These investigations included conducting surveys with clients leaving the DMV about the voter registration services they received in the course of their transactions, and an investigation of local DMV offices. The client surveys sought information on what information the client was provided orally or in writing, how the client interacted with the application forms, and how the client interacted with office personal concerning voter registration. The office investigations included a visual inspection of the office for signage, voter registration forms, and other information concerning voter registration, and interviews with office personal concerning how voter registration is offered and what DMV personnel understand their responsibilities to be.

Appendix C: Variations In State Practice

Reviewing states’ implementation of Motor Voter in conjunction with the results they are achieving in registering voters at DMVs offers a number of lessons about the effectiveness of various procedures and suggests a set of practices states can adopt to increase the number of citizens who are brought into the political process through Motor Voter. To summarize, most states that fall in the lowest Motor Voter Group engage in one or more practices that either violate Section 5 or that discourage voters from registering when applying for or renewing a driver’s license or changing address. Others may be technically compliant with Section 5, but fail to streamline the application process sufficiently to encourage voters to make use of the opportunity to register. Furthermore, many of the practices we have identified demonstrate that states are failing to take advantage of existing or easily implemented technology to streamline their voter registration processes, reduce errors, and bring more people into the democratic process. In contrast, states falling in the high Motor Voter Group have invested in efforts to streamline the voter registration process at DMVs and to tighten the technological linkages between DMVs and elections departments.

In Appendix C, we describe the various practices we observed in each of six general areas, and we assess the effectiveness of these practices by identifying the Motor Voter Groups into which the states using a given practice fall.

A. Integrating Voter Registration into the Driver’s License Application

Many states falling in the high-performing Motor Voter Group have invested significant effort to make registering to vote an integral part of applying for, renewing, or updating a driver’s license. The states achieving the greatest success in registering voters through DMVs integrate the opportunity to register to vote into the driver’s license transaction in such a way that voters cannot overlook the voter registration option. In some states, such as Michigan, voter registration is handled during an oral interaction with a DMV employee. The employee prompts the applicant to choose whether or not to register, and then asks the applicant for relevant voter registration information and transmits the voter registration application electronically to elections officials or prints it for the applicant to sign. Similarly, an increasing number of states—including Delaware and Pennsylvania—are using computer terminals that walk the voter through the voter registration process.

Several states, most of which fall into the middle Motor Voter Group, integrate voter registration into their driver’s license services in a more passive way. Typically, these states incorporate a voter registration application directly into their driver’s license application and renewal forms, fulfilling Section 5’s expectation that the driver’s license application form will itself serve as a voter registration application. See 52 U.S.C. 50204(a)(1). In Texas, for example, the driver’s license application includes the question “If you are a US citizen, would you like to register to vote? If registered, would you like to update your voter information?” The form notifies the applicant that by checking yes and signing the driver’s license application, the applicant is agreeing that she is an eligible voter and that the DMV may transfer the application to the state’s elections office.

In addition, a number of high-performing states integrate voter registration into driver’s license change-of-address transactions as well as into applications and renewals. In other words, the change of address form serves as a voter registration application for a voter who is not already registered and updates the address of a voter who is already registered unless the voter indicates that the address change is not for voter registration purposes. Two of the highest performing states, Delaware and Michigan, provide for voter registration during all driver’s license change-of-address transactions. Pennsylvania, another state in the high performing Motor Voter Group appears to offer voter registration during in-person change of address transactions, but not for changes of address by mail or online changes of address.

At the other end of the scale, several states in the low-performing Motor Voter Group fail entirely to integrate a voter registration application into the driver’s license application, renewal, or change-of-address processes. In the worst offending states—Connecticut for example—the driver’s license forms and accompanying instructions make no reference to voter registration whatsoever, and it is not clear whether or how voter registration is otherwise integrated into the driver’s license application process. More commonly, the driver’s license application asks applicants whether they wish to register, but a—usually blank—voter registration form is provided only to those who answer this question affirmatively. Mississippi, Nevada, and Maine are examples of states that require driver’s license applicants to affirmatively request a voter registration application. States employing this practice violate the command that the driver’s license application itself must include voter registration, and most also violate the no-duplication requirement. See 52 U.S.C. § 20504(c)(1), (2)(A).

In Missouri, during renewal-by-mail transactions, the voter registration application is not provided at the time the renewal form is sent to the voter or submitted to the DMV, but is mailed to the voter after submission—but only if the voter checks a voter registration box—and the voter is instructed to return it to elections officials rather than the DMV. This practice violates not only Section 5’s mandate that the driver’s license renewal form serve as a voter registration application, but also the requirement that voter registration be offered simultaneously with the driver’s license renewal. See id. § 20504(a)(1).

Another way that states violate the mandate that applying for a driver’s license and registering to vote be simultaneous is by failing to accept voter registration applications for transmittal to elections officials or discouraging submission of voter registration applications at the DMV by instructing voters to mail voter registration applications to elections officials. West Virginia’s DMV, for example, instructs voters to submit a voter registration application to state elections officials. The NVRA clearly requires DMVs to accept and transmit voter registration applications. Indeed, Motor Voter achieves its purposes by establishing a single application process whereby an individual can apply for a driver’s license and register to vote in one transaction, and to accomplish this, it makes the DMV responsible for transmitting voter registration applications to elections officials. When voters are made responsible for submitting the voter registration application separately from the driver’s license application, fewer will successfully register, contrary to the goals of the NVRA.

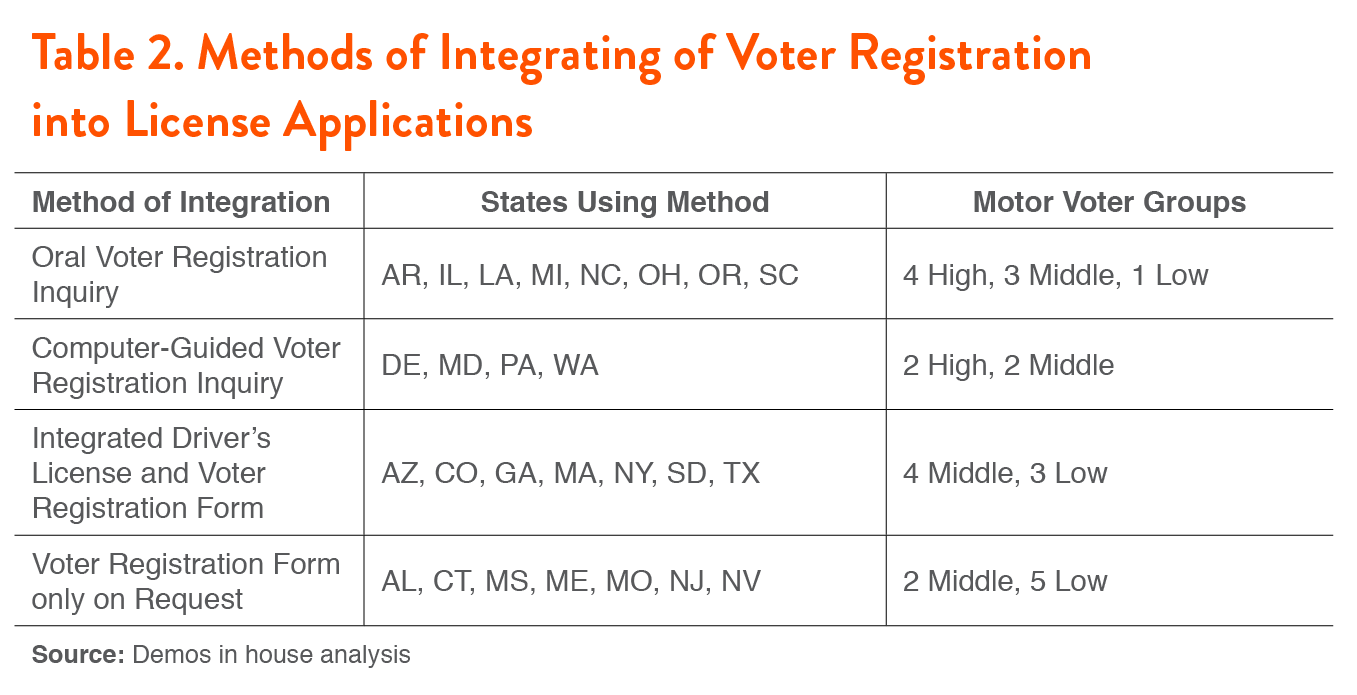

Table 2 illustrates the effectiveness of these varying mechanisms for integrating voter registration. States that require DMV employees to orally inquire about a voter’s desire to register or that use an interactive electronic voter registration system come largely from the high Motor Voter Group, while states that have adopted a passive form of integrating voter registration into DMV transactions—for example, by passively offering voter registration using application forms that serve as both driver’s license and voter registration applications—come largely from the middle and low Motor Voter Groups, suggesting that active engagement with voters is at least as important as providing a streamlined voter registration process. On the other hand, five out of the seven states Demos identified as failing to integrate voter registration fully into their DMV transaction processes come from the bottom Motor Voter Group.

States that fail to integrate voter registration into their driver’s license application or that place the burden on voters to request or submit the voter registration application are among the worst performing states, with five out of seven falling in the low Motor Voter Group. The driver’s license applications in Maine and Connecticut make no mention at all of voter registration, and it is unclear how or whether voter registration services are offered by these states’ DMVs. Mississippi, Alabama, and New Jersey include a question on the driver’s license application asking whether the voter wishes to register, but voter registration applications are provided only if the applicant checks “Yes.”

B. Prohibition on Requiring Duplicate Information

The states that are most effective in registering voters through the DMV have generally taken a robust approach to ensuring their DMV voter registration process does not require voters to provide information that is duplicative of information required for the driver’s license transaction, as required by Section 5. See 52 U.S.C. 20504(c)(2)(A). Most such states require applicants to provide a minimum of additional information to register to vote beyond that provided on the driver’s license application, such as party affiliation, information about prior registrations, and an affirmation of eligibility. Some, such as Michigan, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, use a driver’s license application process that allows the individual to register to vote merely by checking a box on a touchpad or computer terminal or by responding affirmatively to an oral offer of registration. Most require a signature affirming that the applicant meets the state’s voter qualifications. Some states—Delaware, for example—do not require a separate signature, instead treating the signature on the driver’s license application as an attestation of eligibility if the voter has indicated that she is eligible and desires to register. Orally offering voter registration and requiring only a single signature are two of the lowest-barrier and cheapest ways states can incorporate voter registration in their driver’s license application processes in a way that avoids duplication.

Several states, such as North Carolina, Louisiana, and Illinois, produce a separate voter registration application that is pre-printed with the information the voter provided on the driver’s license application, thereby eliminating the need for the voter to enter the same information on both the voter registration and driver’s license applications. The voter need only fill in whatever additional information is required to register (which in some cases is also preprinted after a short interview with the client), sign the voter registration form, and deliver it to the DMV official who is processing the driver’s license transaction.

For states with more limited technology, pre-filling the voter registration form can provide an effective mechanism for reducing barriers to voter registration during DMV transactions provided other procedures are also in place. In particular, providing the voter with the prefilled form must be built into the driver’s license application process and cannot simply be an afterthought. The DMV official must affirmatively solicit submission of the form before completing the driver’s license transaction, as is done in South Carolina, rather than suggesting that the applicant take it away and submit it separately at another time or place. Ideally, the pre-filled form will be provided as a matter of course, whether or not the applicant requests it, unless the driver’s license application clearly indicates the individual is not eligible (most driver’s license applications at least require citizenship information, for example).

Many states, including Texas, Arizona, and Massachusetts, avoid requiring duplicate information by using a single form that serves as both a driver’s license and voter registration application. Typically, these forms contain a discrete section devoted to voter registration in which the applicant can check a box indicating her desire to register or update her registration, select a political party affiliation, and provide a signature affirming that she meets the qualifications to register.

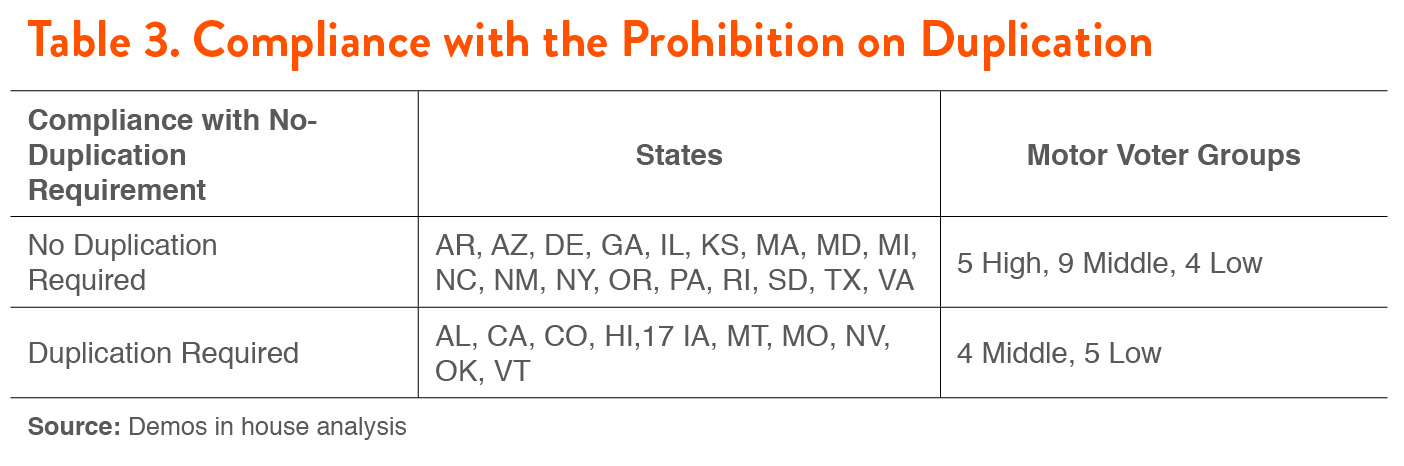

Not all states have taken adequate steps to avoid requiring duplicate information in their DMV Voter registration processes, however. In fact, failure to abide by Section 5’s injunction against requiring duplicate information on the voter registration application is one of the most common and the clearest violations of Section 5 we observed in our research. See 52 U.S.C. § 20504(c)(2)(A). Most states violate the no duplication requirement by merely attaching a blank voter registration application to the driver’s license application (California) or providing a blank voter registration application to voters who check a voter registration box on the driver’s license application (Nevada, Mississippi, Alabama). In other states—including Colorado, Hawaii, and Vermont—the driver’s license application includes a section in which the applicant can register to vote, but the voter registration section nevertheless requires re-submission of information provided elsewhere in the application (see Table 3).

In addition to being widespread, the practice of requiring duplicate information appears to be one of the most significant factors affecting the rate of DMV voter registrations. Almost universally, the states that require duplication of information on the driver’s license and voter registration applications perform poorly in registering voters at their DMVs. In our analysis of state DMV voter registration procedures, we found that the states that require duplication of information from the driver’s license application in order to register to vote, typically on a separate voter registration form, tend to come from the lower Motor Voter Groups. In contrast, we are not aware of any state in the high performing Motor Voter Group that requires duplication of information. Indeed, Delaware and Michigan—the two states with the highest DMV voter registration rate—both integrate voter registration into their driver’s license application forms and procedures with no duplication of information required.

C. Opt-Outs for Change-of-Address Notification