On Income Inequality: An Interview with Branko Milanovic

Branko Milanovic is a World Bank economist and development specialist. He's currently a visiting presidential professor at CUNY's Graduate Center and a senior scholar at the Luxembourg Income Study Center. His book, The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality, examines—as the title suggests—income inequality. Milanovic and Demos Research Assistant Sean McElwee recently discussed Milanovic's research and the major shifts within the inequality research field.

You've been researching inequality for a long time. Inequality as a topic, for a while, was very unpopular. How has the way that inequality is discussed changed in the last decade?

Well, yes, I've been researching inequality, income inequality to be precise, for many years. One could even argue that since the late 1970s to early 1980s it was a topic that had no particular appeal to economists. That is, until five to six years ago.

So then, what happened to change this?

What happened is, I think, first and foremost, the recession. Secondly, the mainstream economics became discredited, not because it could not predict or prevent the crisis, but because it was actually saying, until the very last moment, that the crisis cannot and will not happen.

Plus the realization by many people, when the crisis hit and they could no longer borrow as before, that their incomes had not grown in many years, is what really brought up the issue of inequality. Like, "how is it that some people's incomes have increased a lot and my income stood still?" It was, of course, known by those few who dealt with income distribution before, but it never penetrated much into the economics profession nor into people’s consciousness. Then, with the crisis, things suddenly changed.

One of the things that I thought was most interesting about your work is this idea of the citizenship rent.

You said something like 60 percent of your income is determined at birth and then 20 additional percent by how rich are your parents. I was curious if we included race and gender in that, what percentage of your income do we know before you even begin your pre-K.

Global inequality studies were made possible by two events that occurred at about the same time, in the mid-1980s. First, for the first time ever we had income distribution data for most of the countries in the world. Before, you didn't have household surveys from the Soviet Republics, China and most of Africa. That changed around mid 1980s/late 1980s.

The second thing that changed was, of course, globalization, the inclusion of China and formerly Communist countries in the world market, and thus much greater awareness of the large income gaps between countries and peoples, and of course greater competition.

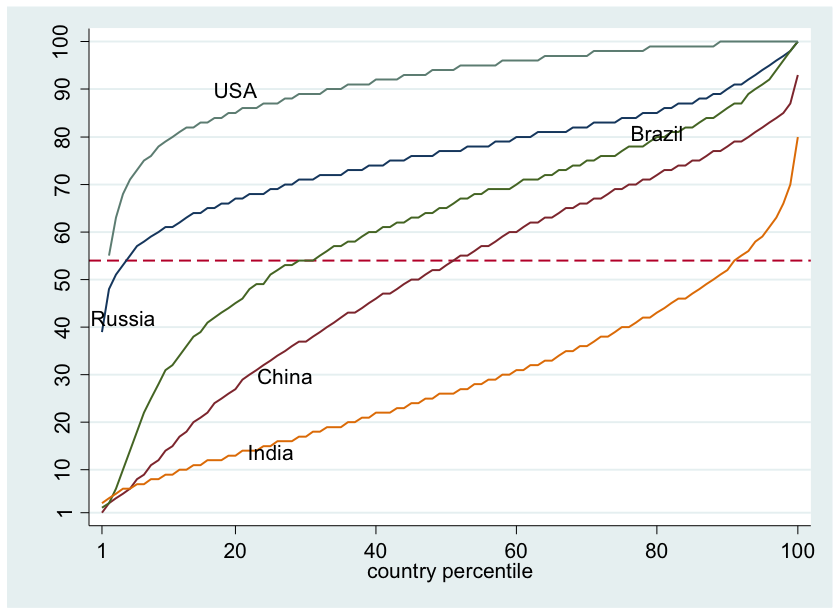

The graph (for year 2008) shows on the horizontal axis a person’s position in their own country’s income distribution, and on the vertical axis, a person’s position in global income distribution. Thus, the poorest Americans (points 1 or 2 on the horizontal axis have incomes that put them above the 50th percentile worldwide). Note that 12% of the richest Americans belong to the global top 1%.

It turns out that—depending on the year and how detailed your data are—some 50 to 60 percent of income differences between individuals in the world is due simply to the mean income differences between the countries where people live. In other words, if you want to be rich, you’d better be born in a rich country (or emigrate there). You can see that in the figure here, where very poorest people in the United States have an income level which is equal to that of the middle class in China or even upper middle class in India.

So that's very striking. At least half of your income is determined by where you live, which for most people is where you were born. Then about 20 percent is due to the income level of your parents. So, your citizenship plus your parental background explain around two-thirds or even 70 percent of your income.

Then, obviously, if I had data for gender, race, ethnicity and other things, which are similarly exogenously “given” to an individual, that percentage would go up, perhaps to more than 80 percent.

So it's at least 80 percent, possibly more?

I am quite confident that if you were to add other things which, I underline, you did nothing to deserve or to be penalized for, you would go, probably, over 80 percent of your income being thus determined.

The lion’s share of that is due to citizenship, or for the individuals like myself who are just residents of rich countries and still get all the benefits, to the residency. This is what I call “the citizenship premium” or “citizenship rent.”

There is more or less a way to deal with inequalities within countries, but how do we deal with inequalities across countries, especially given the way there's the borders? The fact is, if we're worried about the rich controlling the U.S. political system, the rich nations, very much control the international political system.

For global equality there's no mechanism, there are no clear tools, because there is no global government.

Essentially if you think of global inequality, you might say that you have, other than aid, two other tools. One is increase in the growth rate of the poor countries. And this is how, interestingly, you end up in a very curious position, from having started to worry about inequality ending up worrying primarily about economic growth of poor countries.

The second thing is migration. Migration reduces overall inequality on the assumption that when people from poor countries go to rich countries, their incomes go up.

Obviously, migration, while needed to reduce both global poverty and global inequality is not a panacea. Not everything is rosy: first, it could be that the incomes of the people that stay behind are reduced if most skilled people emigrate. This may still reduce global poverty and inequality but it does raise moral issues since we may end up with some countries that would, in the era of globalization, have to disappear: everyone will be better off if they migrated.

And there is a political issue of absorption of migrants in the recipient countries. Still, migration today, despite much attention it receives, has been relatively stagnant and small. In the last quarter of century, the percentage of people who live in the countries where they were not born has been stable at between 2 and 3 percent. Or to go back to your previous question, for 97% of the people in the world, half of their income is decided at the moment when they are born.

Catherine Rampell in her New York Times review of your book, noted income mobility, and I think it gets at this distinction you like to make between good inequality and bad inequality.

The bad or undeserved inequality would be the one that arises from the factors over which you have no control: what was the income level of your parents, whether you were born male or female, what is your race, and things like that.

The good inequality is inequality of effort, work, luck and so on.

Okay. So let's talk about your paper. There's been a lot of recent research on GDP growth and inequality and it's actually kind of shifted almost to the left, it sounds like, with more inequality leading to lower GDP growth. You find that actually it is a little more nuanced than that.

I think that with the paper you mention, which I did in collaboration with Roy van der Weide from the World Bank, the novelty is that we “unpack” both growth and inequality.

In the past, the use of these two aggregate and “unnuanced” measures like GDP per capita and Gini coefficient, regressed on each other across countries, yielded the results that were all over the place: from a positive relationship between high inequality leading to higher growth to a negative relationship, to a very weak or non-existent relationship.

We thought of unpacking both growth and inequality. What does it mean? We don't look at the growth of the mean only; we look at the growth rate at different points of the income distribution, we look at the growth rate of the very poor, say bottom 20 percent of people, we look at the rate of growth of the median, or among the top 10 percent or 5 percent, or top 1 percent.

Then, similarly, [we] disaggregate overall inequality into inequality among the poor, among the rich.

I think our most interesting finding—based on the U.S. data from 1960 to 2010, huge micro-censuses, conducted once every ten years and which include one percent of the U.S. households—is that if you look at income growth of the bottom 20% or bottom 40% of the population in period "t+1", that income growth is negatively correlated with inequality which existed in period "t".

Let me put it in simple terms. Let's suppose I'm a guy who is poor. I live in Massachusetts in 1990. Then the rate of growth of my income between 1990 and 2000, would be negatively correlated with income inequality that existed in Massachusetts in 1990. So we do it across all fifty U.S. states. Obviously, overall growth rates have declined over the last 50 years; also the shape of the growth rates across various income levels (the poor, the middle, the rich) has changed, as you can see here in the graph, but the negative correlation between inequality and subsequent real income growth of the poor remains.

It used to be that the U.S. growth was pro-poor, in the sense, that the growth rates among the poor were higher than amongst the rich. Now it's the opposite. But that particular relationship between inequality and growth of the poor, we find it throughout the entire period. We can only speculate what are the reasons that make inequality be so bad, pernicious even, for the growth at low levels of income.

Source: Roy van der Weide and Branko Milanovic, “InequalityIs Bad for Growth of the Poor,” World Bank (2014) Yearly Real Income Growth by PercentileSelected Decades Income Percentile Income Growth 1960-’70 1980-’90 1990-’00 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0% 5Poorest 10 25 50 Median 75 90 95 99Richest

Now, when you move to the top of income distribution, the story changes. Inequality may not be bad for the rich; actually, it's positively correlated with their growth rates. So if you're really a rich person in Massachusetts in 1990, then your growth rate, between 1990 and 2000 is going to be positively correlated with inequality which existed in Massachusetts in 1990.

In other words, the bottom-line is that we believe is evidence there to show that the rate of growth of the poor people is negatively affected by high inequality.

The argument by many people who are center-left has been, "Oh, we now know that inequality is bad for growth, so the rich should get behind measures to reduce inequality," but if you're correct they actually do not have that political incentive.

That’s a very good point, that’s your point, we don’t make it in the paper, but it’s very true. If you take what we find in the paper, that the growth coefficient on inequality for the rich is positive, then they don’t have an incentive to fight inequality. For their growth rate, inequality is good. It undermines the case for a sort of self-interest of the rich to be more accommodating.