Five Reasons Why Debt-Free College Helps More than Just the Upper-Middle Class

The most important fact about higher education is that only a minority of people go to college. That fact would change if college was affordable for more people.

There has been much joy in progressive circles this week, as Hillary Clinton’s campaign has floated an embrace of debt-free higher education, following broad statements of support from other candidates as well as a group of influential Senate Democrats.

As with any bold idea, there has been some mild pushback as to who stands to benefit. This morning, the Washington Post’s Wonkbook picked up on an argument made by The Week’s Ryan Cooper that debt-free college (broadly defined) would primarily benefit the upper middle-class:

However, the most important fact about higher education is that only a minority of people go to college. Though the proportion of people with a college degree has been rising for a long time, as of 2012, only about 40 percent of the population held a two-year degree or higher. That 40 percent, of course, overwhelmingly overlaps with the upper 40 percent of America's income distribution.

This is a strain of thought that has existed for some time—that tuition or loan relief would primarily be a sop to Americans that are already in good financial shape—but it misses the point, and even the structure, of debt-free college in important ways.

1. Reducing the cost of college could make more low-income students attend.

A major reason that the mix of college attendees and graduates skews wealthy is simply because the price of attending has gotten so high. Put another way: poorer students and families aren’t going to college because they can’t afford it. As the University of Wisconsin’s Sara Goldrick-Rab notes in her exploration of free two-year college, we have nationally representative data that indicates that qualified and talented students who are concerned about rising college prices are 12 to 16 times more likely to forgo college altogether. There’s plenty of research on cost as a barrier to attending college, and that reducing the net cost of college on low-income families has positive effects on enrollment, persistence, and completion. That we’ve basically made borrowing a requirement to attending (and certainly to completing) college makes the prophecy that college degree is an endeavor for the wealthy self-fulfilling.

2. Student debt is most burdensome on non-graduates. And there are a lot of non-graduates.

Cooper and others have naturally made the accurate point that a college degree still pays off; in other words, graduates with student debt on average don’t face massive financial ruin because of the value of the degree.

There are two reasons why we shouldn’t be so rosy though. The first is that the most successful students “doing okay” is a pretty low bar for whether we should maintain our debt-based system going forward—we have plenty of evidence that even those who can meet their monthly payments are still struggling with student debt, or shifting other savings and financial needs aside to pay off their loans. The second is more important: A very large portion of students never graduate.

The defense of student loans boils down to the assumption that taking on loans for college means you’ll finish college. But we know that a substantial, and growing, portion of students not only drop out—but they drop out with debt. And these are the students who are most likely to struggle to repay or default on their loan.

Or alternately, if they have a healthy fear of debt, they may not attend college full-time, or work longer hours, reducing their likelihood of graduating as well. In essence, our requirement that students take on debt has dramatically increased the risk of not graduating. Basically, today’s students are stuck with a Catch-22: take on loans, or engage in behavior—part-time enrollment or full-time work—that decreases the likelihood that they will complete a degree.

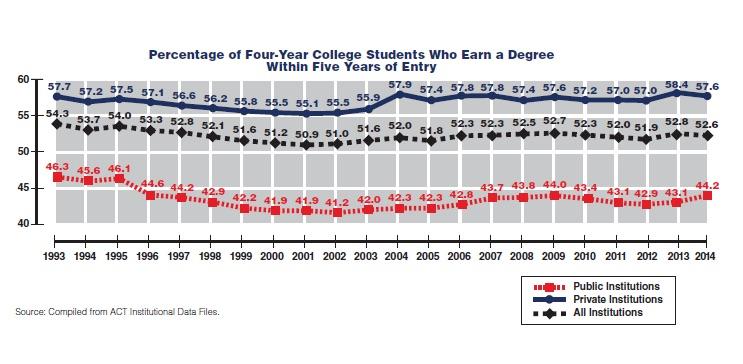

In a world where we have failed to increase college graduation rates, debt-free higher education would at least remove some of the risk of going to college.

3. Students of color and low-income students really are bearing the burden of undergraduate debt.

Decades of public disinvestment in higher education have coincided with the federal government failing to increase need-based grant aid (like Pell Grants), which are targeted at low-income students. Because Pell Grants cover far less of the cost of college than they used to, we actually have shifted the cost of college onto the backs of our least vulnerable. Low-income students are required to pay a far greater portion of their family’s income in unmet college costs:

Low Income Families Must Spent the Vast Majority of Their Income on Unmet Need

Net Cost of College, After Grant Aid, As a Percentage of Family Income

|

Public 4-Year |

Private 4-Year |

|

|

Bottom Quintile |

74% |

82% |

|

2nd Quintile |

41% |

57% |

|

3rd Quintile |

29% |

41% |

|

4th Quintile |

22% |

31% |

|

Top Quintile |

14% |

21% |

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2011-12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:12). Percentages are for dependent students attending college full-time for a full-year

The marginal impact of removing that unmet need—which would be accomplished by debt-free college—is actually quite progressive.

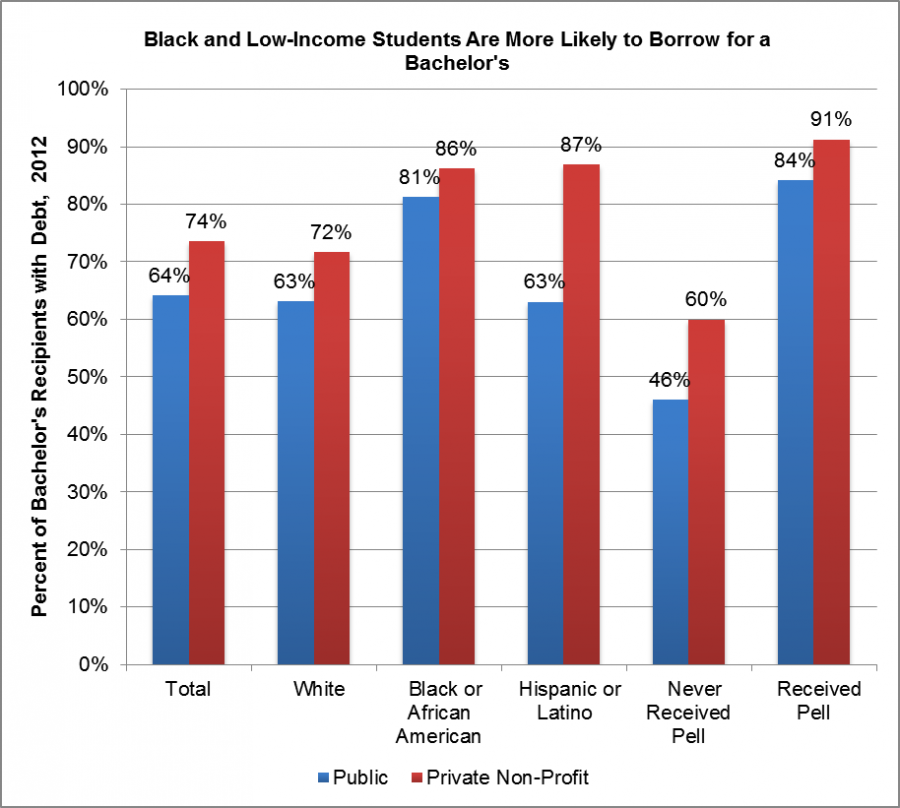

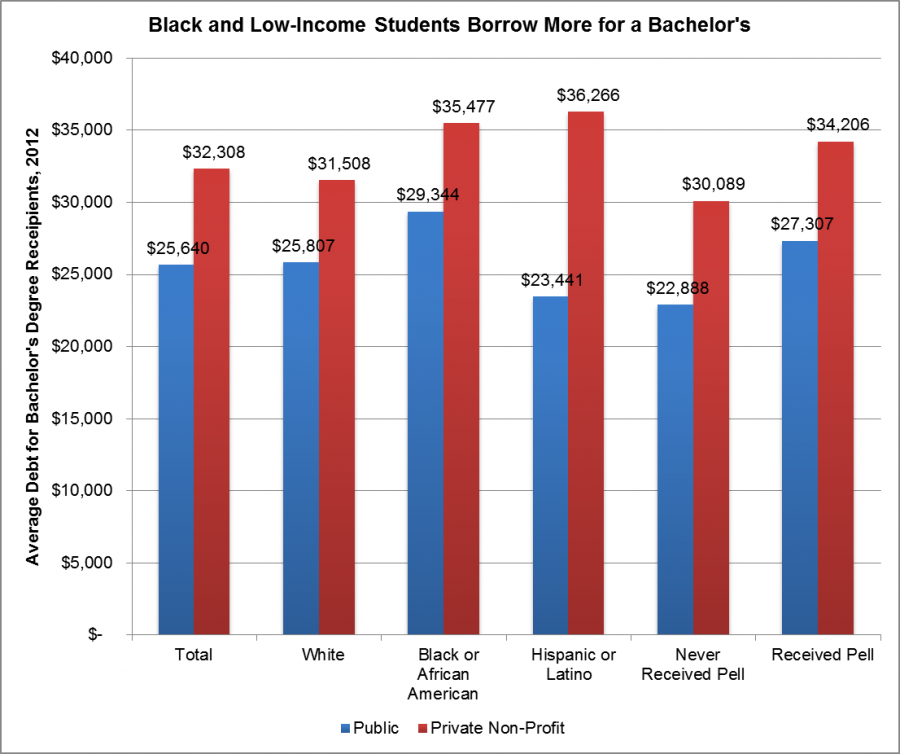

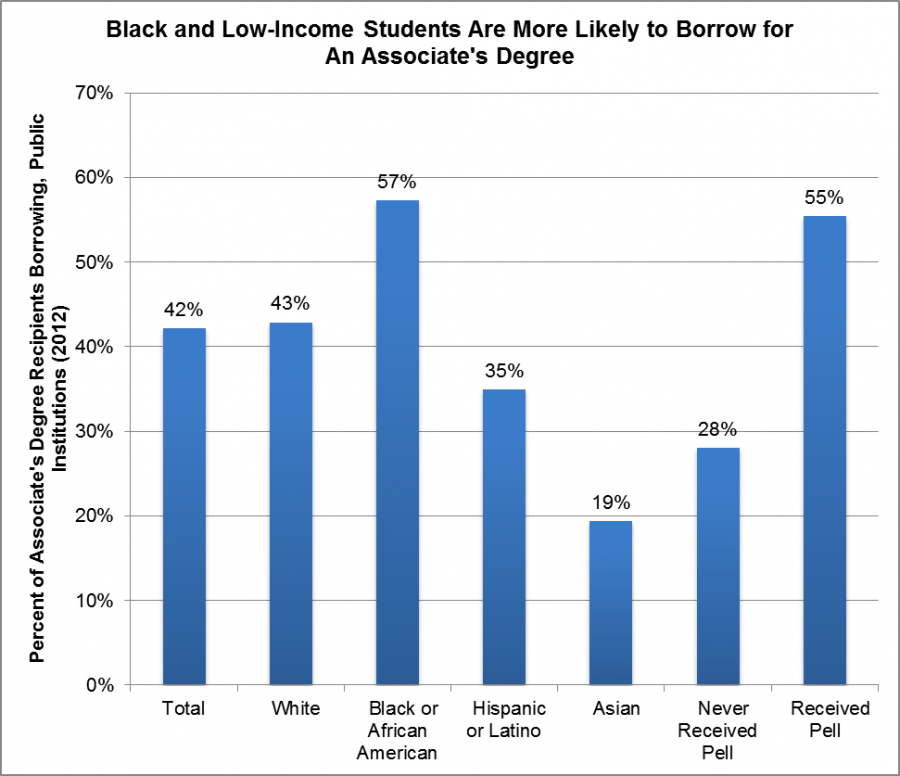

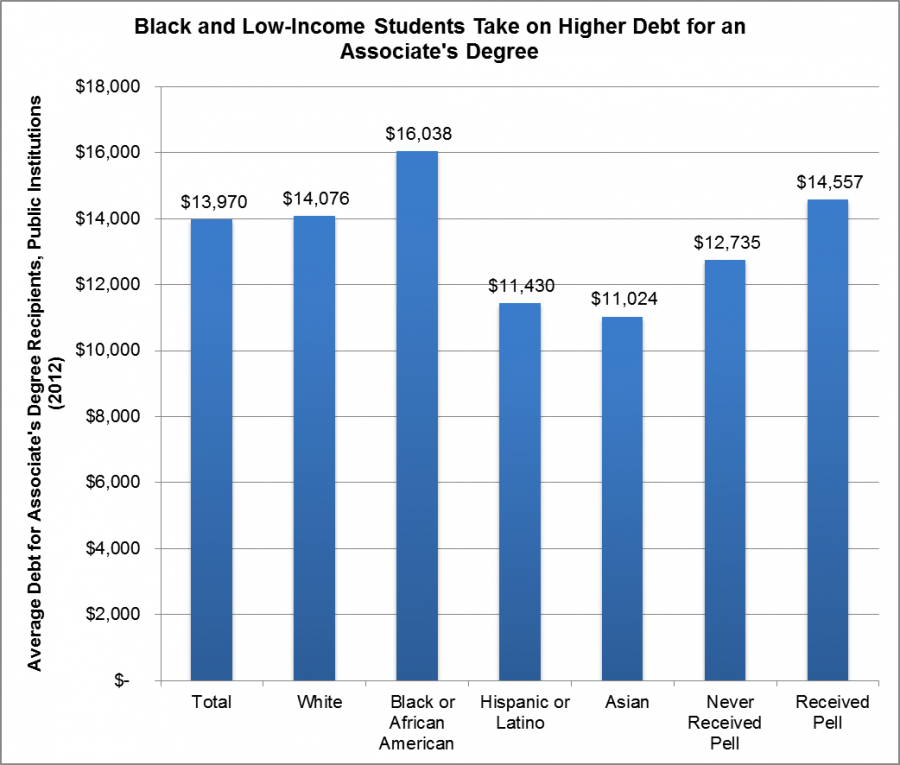

And again, if you look at the debt levels of graduates, it’s pretty clear that we’re asking more of underserved students than we are of anyone else:

(Source: Calculations from the U.S. Department of Education National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2012)

4. Debt-free college doesn’t necessarily mean free tuition.

One of the fundamental misunderstandings in this debate is that many are conflating “debt-free college” with “free tuition.” But these distinctions are important.

On one hand, free tuition would only cover the direct costs of attending college and not the total cost, leaving many low-income students with substantial bills to pay—living expenses, books, computers, transportation, child care, and other fees—that are baked into colleges’ Cost of Attendance (and which also help determine how much students can borrow). Making tuition free wouldn’t make college debt-free, and without substantial need-based aid, low-income students would still face high net costs.

But debt-free college is different. The assumption underlying debt-free college is that a student can be guaranteed to cover any college costs without borrowing. This, of course, means that a student could work a reasonable amount—say 10-15 hours a week—during the school year or summer, with enough grant aid to keep unmet need low enough to be covered by working. It means that we should be targeting our resources toward students who have no choice but to borrow because of their family financial circumstances.

A guarantee of debt-free college also does not necessarily mean debt-free private college, which educate a disproportionate number of wealthy students. It would simply create a true public option for those who wish to take advantage of it.

5. We actually used to invest in debt-free college.

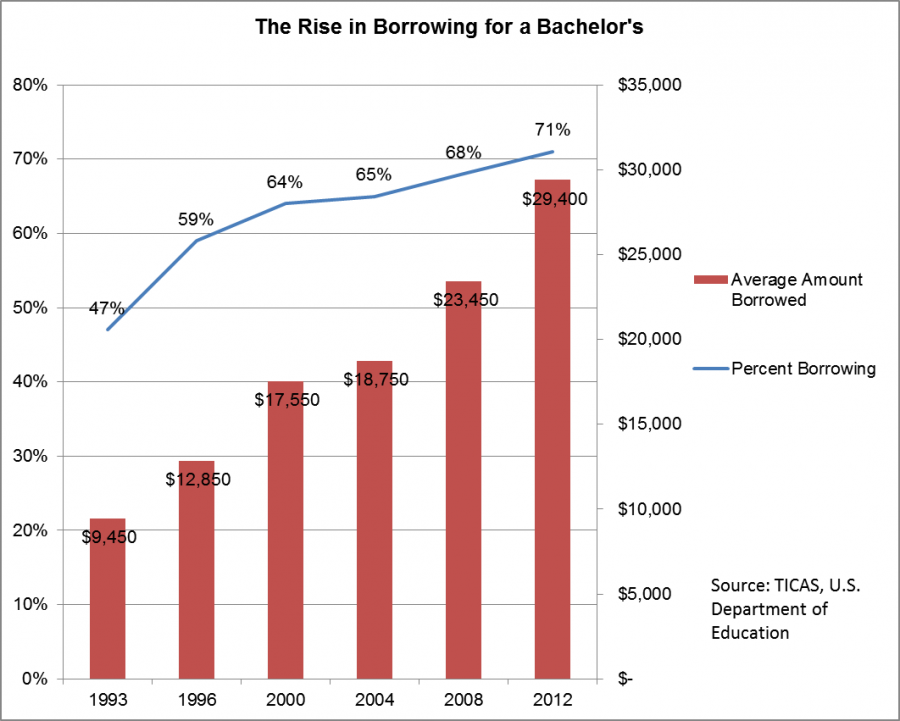

Historically, our system relied states covering the vast majority of college costs, and the federal government targeting resources toward those who need additional help financing it. The result was that, up until about 20 years ago, student debt was the exception, not the rule, for those who wanted a bachelor’s degree:

The anecdote about being able to pay for a year of college with a summer job is not only true, but it is a direct result of our willingness to invest in public higher education at the per-student levels that the system was designed to do. This divestment was in part caused by a move toward lower tax revenue, particularly at the state level (and in a manner that primarily benefited high-income families).

Unfortunately, in addition to divesting, we have allowed billions in public resources—from student aid to veterans benefits—to be used at private and for-profit institutions, many of whom either do not need the extra resources or do not provide much in the way of quality. Debt-free college could be paid for in an efficient, and yes, progressive fashion.

But by saying that debt-free college would primarily help upper-middle class students, critics are implying that the system is more progressive today. Given what we know about the ability of high college costs and student debt to shunt access, prevent completion (or increase the risk of not completing), and the financial circumstances of those who struggle the most, it’s not really an argument that holds up.

UPDATE

It also occurs to me that the 40% figure – the percent of the population with a degree – is not at all the right number to look at here. First, as mentioned, it's basically tautological: Costs have made college access skew toward the wealthy, and therefore the wealthy attend and get degrees. The point of debt-free college is to broaden access (as well as access to degrees) to those who don't have it now. Mainly though, it underestimates who stands to benefit: The percentage of young Americans who have attempted college is actually much higher: 64% among those age 25-29, and 58% among all those above 25. After all, debt-free higher ed stands to benefit these students as well – whether or not they graduate. In addition, we know that 66% of high school graduates immediately transition to college, including 49% of low-income students. Obviously, something like debt-free college aims to increase attendance and graduation rates for low-income students (and thus reduce the gap), but it would also stand to benefit a much higher number of people that has been suggested.