Beyond Colorblind—Retail’s Opportunity to Advance Racial Equity

On Monday the Supreme Court handed down a decision against Abercrombie & Fitch, ruling 8-1 that the retailer’s “look policy” discriminated against a job applicant on the basis of religion. The policy required that staff conform to the company’s ‘All-American’ brand image, and the job applicant was a young All-American Muslim woman who came to her interview wearing the headscarf she dons as part of her religious observation. To the company’s hiring managers, covering your head was not Abercrombie cool.

It is not the first time the company has come under fire for a policy that was deliberately exclusionary. In 2004 Abercrombie settled an EEOC lawsuit on the basis of racial and gender discrimination for $50 million. In 2009 a UK tribunal determined that the retailer unlawfully harassed a worker for reasons related to her disability and that she was wrongly dismissed. In each of these cases, including the most recent, Abercrombie defended their policy but also ultimately reevaluated it. In accordance with the 2004 agreement, the company created an office of diversity, improved training for managers, and monitored the results. The policy that barred the young woman with the headscarf from employment is no longer in effect.

The Abercrombie & Fitch settlements, as well as other recent high-dollar settlements at retailers like Walmart, Walgreens, and Wet Seal, show that even in 2015 discrimination remains a problem in the labor market. In contrast to textbook economic theory, competition has not eliminated discrimination—in fact some companies’ marketing tactics depend on it.

But retailers do not have to practice direct discrimination for their employment policies to result in disparate effects across different racial and ethnic populations. Instead, neutral-seeming practices often reproduce inequities that have been embedded in the labor market since before the Civil Rights Era.

In a recent paper with NAACP, The Retail Race Divide: How the Retail Industry is Perpetuating Racial Inequality in the 21st Century, we show that Black and Latino workers face significant challenges in retail employment, with lower typical earnings and less representation in management roles. Those characteristics are not unique to retail, but as a large and growing source of jobs for workers of color, employers in that industry have an important chance to effect change through practices that lift up the workforce as a whole.

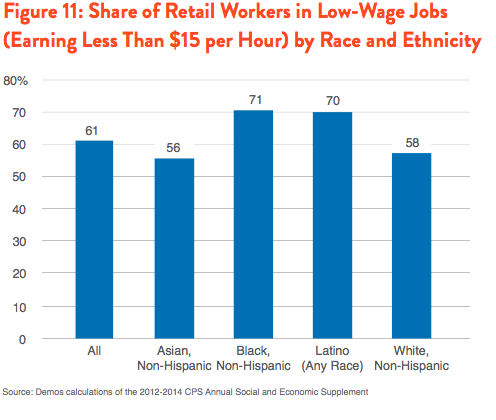

Take the earnings differential, for example. Since retailers disproportionately employ Black and Latino workers in lower-wage jobs, raising wages at the bottom will reduce the racial wage divide. If retailers met workers’ call for $15 per hour today, it would affect 70 percent of Black and Latino retail workers, move the median Black and Latino wage closer to that of White and Asian workers, and cut working poverty among the entire retail workforce in half.

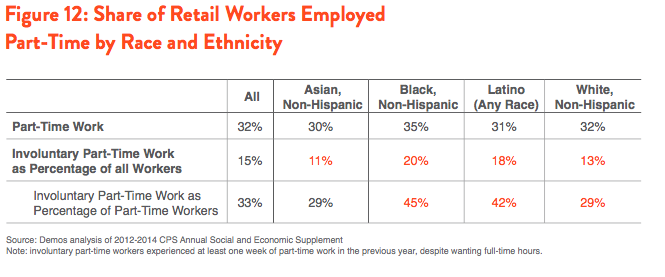

And since wages times hours on the clock equals a retail paycheck, employers could go a long way toward promoting equity in the industry by adopting responsible scheduling practices too. Among Black and Latino part-time retail workers, more than 4 in 10 would prefer to have full-time hours but cannot get them.

Schedules that change from week to week exacerbate these problems and make it more difficult for retail workers to manage their finances, households, and futures. Reducing involuntary part-time employment and just-in-time scheduling practices for all workers would help turn retail jobs into real opportunities to thrive through work. It would also make a meaningful contribution to racial equity, since people in the Black and Latino part-time workforce are more likely to be there involuntarily, and since erratic scheduling adds to burden of existing disparities.

It would be exciting for big employers to step up to the plate on issues of racial equity, and turn their attention to making retail jobs real opportunities even without grounds for litigation. Of course, retailers are also entitled to say ‘it is not our responsibility, we just found it this way,’ and continue to perpetuate the inequities that filter from market to market, entrenching the racial divide. And that’s why we have public policy.

With more than four decades of evidence that markets won’t do it alone, it’s time to recommit to an economy that provides everyone an equal chance and to stop ignoring racially biased outcomes while stigmatizing those workers who are worst affected by them, carrying the institutions of racism into the 21st century. Taking responsibility for a market that reproduces racial disparity means taking the opposite of a ‘colorblind’ approach; it means paying attention.

In New York we recently took one step toward ending the systematic exclusion of Black and Latino workers from job opportunities when we banned employers’ use of credit history, which is a common ‘colorblind’ way of screening job applicants that has disproportionate negative impacts on Black and Latino workers with no proven benefits for the hiring firm.

In San Francisco, two ordinances known together as the Retail Workers’ Bill of Rights protect the workforce from the worst scheduling abuses and redistribute the costs of holding down a retail job. The policies promote access to full time hours for workers that want them, reduce the burden of on-call shifts, and increase the predictability of hours and paychecks.

And across the country, the movement to raise the minimum wage has already ensured that more workers at the bottom have a real stake in our shared economic success.

Policies such as these can have the double impact of reducing racial inequities in the labor market while promoting jobs that increase economic security for workers overall. As the country continues to focus on the problems associated with inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity, we will identify more chances to reduce racial disparities—but only if we look.