Key Findings

This paper examines the differences in retail workers’ occupations, earnings, and schedules to reveal how employment in the retail industry fails to meet the needs of the Black and Latino workforce and, as a result, perpetuates racial inequality. Consistent disparities in labor market outcomes demonstrate the failure of markets to advance racial equity since the 1960s, even after decades of equality in law. As one of the largest sources of new employment in the US economy, and the second-largest industry for Black employment in the country, the problems of occupational segregation, low pay, unstable schedules, and involuntary part-time work among Black and Latino retail staff point to an important chance for employers to make a real impact on racial inequality by paying living wages and offering stable, adequate hours for all retail workers.

Black retail workers share the attributes of the overall retail workforce, but face worse outcomes.

- Like the overall retail workforce, the vast majority of Black retail workers are adults. More than half have some education after high school, and about one-third are working parents.

- Yet Black and Latino retail workers are more likely to be working poor, with 17 percent of Black and 13 percent of Latino retail workers living below the poverty line, compared to 9 percent of the retail workforce overall.

Retail employers sort Black and Latino retail workers into lower-paid positions and away from supervisory roles.

- Black and Latino retail workers are underrepresented in supervisory positions like managers or first-line supervisors. Black workers make up 11 percent of the retail labor force but just 6 percent of managers.

- Black and Latino retail sales workers are overrepresented in cashier positions, the lowest-paid position in retail.

A racial wage divide exists in the front-line retail salesforce.

- Retail employers pay Black and Latino full-time retail salespersons just 75 percent of the wages of their white peers, amounting to losses up to $7,500 per year.

- Retail employers pay Black and Latino full-time cashiers about 90 percent of the wages of their white peers, amounting to $1,850 in losses per year.

- Retail employers pay 70 percent of Black and Latino full and part-time retail sales workers less than $15 per hour, compared to 58 percent of White retail workers.

Black and Latino workers face greater costs associated with part-time and “just-in-time” scheduling.

- Black and Latino retail workers are more likely to be employed part-time despite wanting full-time work. One-in-five Black retail workers are employed involuntarily part- time, compared to less than 1-in-7 white workers.

- On-call, unstable, and unpredictable schedules pose costs to employees that exacerbate the problems associated with occupational segregation and the racial wage divide.

Retailers have an opportunity to make changes that will reduce racial disparities and improve living standards overall.

- A raise to $15 per hour would affect 70 percent of Black and Latino workers and cut rates of working poverty for the entire retail workforce in half.

- A raise to $15 per hour would reduce the racial wage divide.

- Ending involuntary part-time work would reduce poverty by at least 2 percent, with greater effects on the Black and Latino working poverty rates.

- Introducing fair scheduling practices would improve working conditions and contribute to equal opportunity in the labor force.

Introduction

When Walmart CEO Doug McMillon recently announced a modest raise for the company’s lowest-paid workers, the news captured national attention. That’s because the retail giant is not only America’s biggest company—ranked number one on the Fortune 500 with $486 billion in revenues last year—it is also the country’s largest private employer. Walmart is a leader whose pay practices and working conditions have the potential to impact jobs across the retail landscape and beyond. And at a company famous for achieving massive profits through innovative and unrelenting cost containment, raising the bottom threshold for worker pay demonstrates that the low-wage economy is not working for Walmart’s bottom line. Walmart’s evolving business model is also a first-glimpse at how the low-wage strategy is failing the American economy broadly. Across industries, the business decision to leave workers out of economic gains has perpetuated three decades of stagnant household income and more than half a century of employers allowing entrenched racial inequities to go unchecked. But retailers today have an opportunity to make a different business decision, one that truly leads the way to the opportunity and equality at the heart of the American Dream.

Right now, low-wage retail jobs like those at Walmart are among the most common occupations in the country, and the fastest growing. Yet the years of slow recovery that followed the Great Recession of 2007-2009 revealed a problematic trend: service industry employment became more central to the well-being of American workers, but the low wages and uncertain schedules that characterize that employment undermined household financial security and, by extension, growth and stability for the economy overall. In this context, the labor market disadvantages associated with persistent racial inequality and discrimination make Black and Latino workers and their families increasingly vulnerable to the worst implications of low-wage, unstable working conditions. Addressing these racial inequities provides a starting point to advance an economy that works for all.

Diversity in the retail industry is comparable to the labor force as a whole, with White, non-Hispanic workers accounting for two-thirds of those employed in the industry and the other one-third composed of people of color. Another similarity to the overall workforce is a persistent opportunity gap for the Black and Latino retail workforce. Our research indicates that, like in other sectors, people of color are overrepresented in the positions with the lowest pay and the least stability and underrepresented in management positions. At the same time, Black and Latino retail workers are significantly more likely than White workers to be employed part time when they want full-time hours, making it difficult to meet their families’ basic needs. Just-in-time scheduling practices like on-call shifts or being released from shifts when store traffic slows can exacerbate these problems and make it nearly impossible to plan a household budget.

This occupational segregation by race and ethnicity is prevalent across sectors of the American economy. It is a conduit for the racial inequities in labor market outcomes and perpetuates the institutions of discrimination made illegal by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act more than 50 years ago. The persistence of these practices carries the most repugnant features of American history into the 21st century, but like many of our previous institutions of racism, they can be transformed. As one of the largest sources of new employment in the US economy, and the second-largest source of jobs for Black workers in the country, the problems of occupational segregation, low pay, unstable schedules, and involuntary part-time work among Black and Latino retail staff point to an important chance for employers to make a real impact on racial inequality by paying living wages and offering stable, adequate hours for all retail workers.

The insecurity and meager pay too common in retail employment builds on generations of labor market history for workers of color—in the retail industry and beyond—who face a distinctively precarious labor market even under the best economic conditions. Across the economy, Black and Latino workers experience challenges associated with discriminatory practices and a persistent wage divide. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), in 2013 the median full-time Black worker earned just 78 percent of the median full-time White worker’s income, a racial earnings divide that is even worse among sales occupations. The 2013 measure is typical of the American workforce, which has shown no evidence of converging toward earnings parity by race or ethnicity over the 35-year lifetime of the measure. In fact, research from the Economic Policy Institute shows that the median Black family’s income today is smaller as a share of the median White family’s income than it was at the end of the Civil Rights Era 50 years ago. Employment trends exhibit a similar lack of progress, with Black workers unemployed at about twice the rate of White workers over the last 50 years. These consistent disparities demonstrate the failure of markets to advance racial equity, even after decades of equality under the law. Not only has the labor market not improved for Black workers relative to White workers, the disparity in earnings for Black and White families has actually gotten worse.

The combination of an opportunity divide, employment divide, and wage divide throughout the economy result in what labor economist Steven Pitts has termed a “two-dimensional jobs crisis” facing Black workers. The first dimension of the crisis manifests in the high rate of Black unemployment, even during periods of sound economic growth. The second dimension of the Black jobs crisis is the problem of low wages, which in the retail industry often combines with destabilizing workplace policies like erratic scheduling. Decent employment opportunities, wages, and workplace practices are the essential bedrock for all Americans to be able to work toward an adequate, dignified standard of living. Yet our labor market norms have consistently excluded people of color from accessing those foundations of opportunity. Addressing the two dimensions of the jobs crisis in the Black community will require national-level action to improve working conditions, but the fiscal policies that address unemployment are not enough on their own. Labor market policy needs to target not just the national rate of full employment, but full employment for minorities like Black and Latino workers coupled with higher labor standards for all.

Any effective remedy for the two-dimensional jobs crisis will require a partnership between the public and private sectors to eliminate the limits to opportunity that hold Black and Latino workers back. For retail firms, that means a commitment to ending discriminatory practices, whether they are the product of interpersonal prejudice or disparate impact. For example, in recent years several large retailers, like Walgreen’s (2007), Walmart (2009), and Wet Seal (2012), have entered multimillion-dollar legal settlements for discrimination against Black workers in areas of hiring, promotion, compensation, and termination. These cases expose the diffuse need for better company policies, management training, and pursuant monitoring across retail stores and at all levels of employment. Enforcing these non-discriminatory practices would not only benefit the workforce, but allow companies to reap the benefits of the full scope of available labor.

Retailers should likewise address employment policies that perpetuate racial disparity still remaining within the law. For example, retailers who rely on credit checks as a routine way to screen job applicants reinforce the discrimination that occurs in housing, lending, and employment markets broadly, despite a lack of evidence showing any relationship between credit history and job performance. As a result, employers create an unnecessary barrier to hiring qualified workers that exacerbates existing racial disparities.

But the broadest impacts on racial equity can be advanced with policies that lift up the retail workforce overall. Raising wages for the lowest-paid workers to $15 per hour would bring the median full-time Black retail sales worker within 97 percent of the current hourly wage of the median full-time White sales worker, while lifting millions of workers and their family members out of poverty or near-poverty. At the same time, ending the destabilizing practices of just-in-time scheduling policies like on-call shifts and unpredictable hours would provide workers and their families with renewed financial security and control. In 30 years, the majority of Americans will be people of color, and today’s discriminatory employment practices will exclude larger shares of the population from real opportunity in the workforce. Replacing these exclusionary practices with jobs that raise up workers is essential to building a nation of prosperity and opportunity for all.

This paper examines the differences within the retail industry by breaking down race and ethnicity to reveal how employment in this field fails to meet the needs of the Black and Hispanic workforce and, as a result, perpetuates racial inequality. The findings are drawn from analysis of the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement pooled over the years from 2012 to 2014. We find that the high demand for workers in the retail industry has not engendered employment stability for these workers and their families. Instead, even more households experience the hardships associated with paychecks that are unpredictable as hours fluctuate from week to week, and wages that fall short of meeting a family’s basic needs even with full-time hours. These conditions leave nearly one in 10 retail sales workers in poverty, despite being employed. This number is even higher among Black and Hispanic workers who, not only, face prevalent low-wages and unstable scheduling practices, but the additional obstacles of racial inequality in the labor market. However, the findings also point the way forward. Retailers today face a unique opportunity to partner with their communities to improve financial stability, economic performance, and racial equity by paying living wages accompanied by stable and adequate hours for all workers. By lifting up workers at the bottom, retailers can meet the dual needs of addressing racial inequality in the labor market and raising living standards for retail workers as a whole.

Retail Demographics

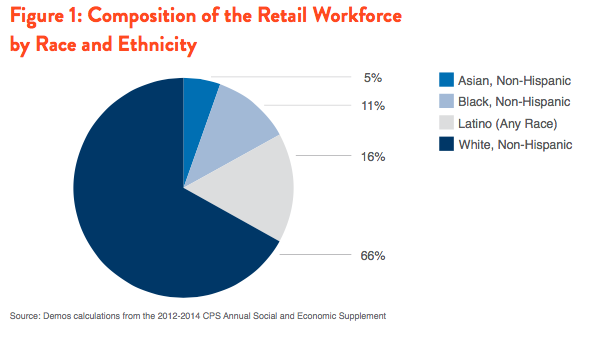

There are more than 15 million people working in retail jobs today, accounting for more than 1 out of every 10 employed workers in the country and 1 out of every 6 private sector jobs added to the economy last year. Among Black workers, retail is second only to the broadly inclusive Education and Health Services industry as a source of employment. More than 1.9 million Black workers are employed in the retail industry, as are 800,000 Asian American workers, more than 2.3 million Latino workers, and nearly 10 million White, non-Hispanic workers who make up the largest share of retail employment. Yet despite a high and growing demand for retail workers, jobs in the industry frequently fall short of meeting workers’ needs. For Black and Latino retail workers, the outcomes are even worse.

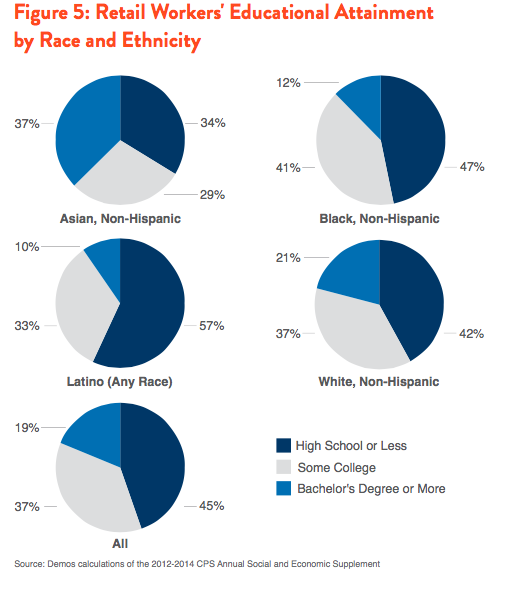

The population of Black retail workers closely resembles the retail workforce overall, yet these same Black workers are more likely to be working poor (see Figure 1 for composition of the retail workforce). Like retail workers in general, half of Black and half of Latino retail workers are female and more than 90 percent are ages 20 or older (see Figures 2 and 3). Similarly, about one-third of retail workers are parents caring for children at home—33 percent of White workers, 35 percent of Black workers, 40 percent of Latino workers, and 35 percent of workers overall (see Figure 4). Just over half of all retail workers have some educational experience beyond high school, though White and Asian workers are still the most likely to have completed a degree (see Figure 5). The big difference, however, between White, Black, and Latino retail workers, is that Black and Latino retail workers are more likely to earn poverty-level incomes.

Although there is a persistent conception of retail as a stepping stone to better employment, the truth is that for many workers these jobs are central to sustaining homes and families. About half of all retail workers contribute at least 50 percent of their household’s income with their retail paycheck (see Figure 6). Black workers are most likely to be the sole earner in the household—a finding that should not come as a surprise in the context of routinely high Black unemployment across sectors, making it more difficult for other family members to find jobs.

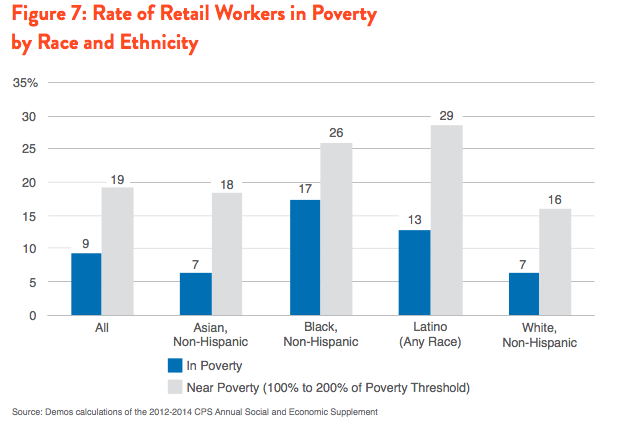

Nine percent of all retail workers live below the official poverty line, a higher share than among the workforce as a whole. Another 19 percent live near poverty, with household earnings between 100 and 200 percent of the poverty threshold (see Figure 7). Together, that means more than one in 4 retail workers are poor or living on the edge of hardship. But Black and Latino retail workers are significantly more likely to be working poor than the retail industry as a whole. Seventeen percent of the Black retail workforce lives below the poverty line, compared to 7 percent of White and 13 percent of Latino retail workers. In addition, more than a quarter of Black and Latino retail workers live within 200 percent of the poverty line, compared to just over one-sixth of White retail workers. Altogether, more than 40 percent of Black and Latino retail workers are in or near poverty, despite holding down a job.

With high poverty rates among all workers and exceptionally high rates for Black and Latino workers, it is clear that retail is not meeting the needs of its workforce. In the following sections we investigate the sources of working poverty and racial disparity in retail employment, and show how retailers could improve working conditions to make retail a sector where equal opportunity thrives.

Employment Credit Checks: An Unfair and Unnecessary Barrier to Opportunity

Employers often rely on credit screening as part of the process for hiring new workers, so bad credit can pose a critical barrier to opportunity in the labor market. In retail, occupations from entry-level to management may be subject to employment credit checks for hiring and promotions. But investigating a job candidate’s credit history is not telling employers what they need to know, and evidence suggests that the practice perpetuates racial biases in wealth, lending, and employment, and keeps qualified people of color out of work.

Almost half of American companies have adopted employment credit checks as a regular part of hiring, despite the absence of evidence showing a relationship between credit history and job performance. Credit reports were not developed for employment screening, but rather to provide lenders with an evaluation of the economic stress on a potential borrower in order to gauge their ability to repay a loan. That information includes experiences with foreclosure, bankruptcy, and falling behind on bills—the kind of experiences that are associated with insufficient income or spells of unemployment. As a result, rather than indicating trustworthiness, loyalty, or job skills, poor credit history is more likely to reproduce broader conditions of economic inequality in the US economy.

In our recent report, The Challenge of Credit Card Debt for the African American Middle Class, we found that moderate-income Black households with credit card debt are less likely than similar White households to report good or excellent credit, a finding that aligns with other research identifying racial biases in credit scoring, including research from the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Brookings Institution. The poor credit scores of Black and Latino households relative to Whites reflect current and historical racial inequities in lending, housing, and employment. These differences include the greater likelihood of unemployment and inadequate insurance coverage among Black and Latino households, and disparities in wealth accumulation that persist from post-war era policies that favored Whites, as well as more recent discriminatory practices focused in Black and Latino communities, such as redlining and predatory lending.

There is another reason that credit screening makes a poor tool for evaluating job applicants: credit reports are frequently wrong. A 2013 study from the Federal Trade Commission found that 1 in 5 people had a material error in a credit report. Workers may not realize that inaccuracies in their credit history are thwarting their job search, and even if they do, correcting the error can be a time-consuming burden.

These biases and inaccuracies in credit reports reveal the growing need for policy to address the discriminatory practice of employment credit checks that keeps qualified people out of a job. Ten states have already enacted restrictions on the practice, and 53 percent of companies voluntarily refrain from checking credit as part of their human resources policy. But the persistence of this unfair and unnecessary barrier to employment calls for targeted solutions, including greater accuracy and transparency in the credit reporting industry and an end to employment credit checks. The Demos report Discredited: How Employment Credit Checks Keep Qualified Workers Out of a Job examines these issues in greater detail. A system of credit reporting and scoring that reproduces racial and economic inequality serves neither workers nor employers and undermines the economic security of Black and Latino households. In ending employment credit checks, retailers have a costless opportunity to advance racial equity and improve economic opportunity for all.

Occupational Segregation

Employment in the retail industry spans a range of responsibilities and pay grades, from customer service to CEO, but Black and Latino workers are sorted into the occupations that are most likely to be low-paid and part-time, like cashiers. That sorting reproduces a persistent wage divide that leaves Black and Latino retail workers more likely to be working poor.

Across the economy, Black and Latino workers are less likely to work in professional, management, and related occupations—the highest paid occupational category in the labor force. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2013 Black workers were 11 percent of those employed, but held just 7 percent of management jobs. Similarly, Latino workers composed 16 percent of employed workers, but 8 percent of management jobs. At the same time, White and Asian workers were overrepresented in management occupations, and Whites experience increasing overrepresentation at the highest corporate levels, like among CEOs where more than 91 percent are White.

Retail replicates these disparities, with Black workers in the industry making up just 7 percent of management and professional occupations, like senior staff in human resources, public relations, administration, or sales (see Figure 8). These jobs tend to offer higher pay and steady, full-time hours, resulting in annual incomes well above the median for retail and for the economy as a whole. In a labor market with equal opportunity, the racial composition of an occupation category like management would look much like that of the industry overall. Instead, Black retail workers report employment in management and professional jobs at a far lower rate than White workers.

In contrast, just over half of all jobs in the retail industry are sales or sales-related positions like cashiers, customer service, and stock clerks, and Black, White, and Latino workers are equally likely to report falling into this group. Many of these positions provide a company’s first point of contact with customers and demand exceptional interpersonal skills, dexterity, and knowledge of store organization, merchandise, and security practices. The three most prevalent jobs—retail salespersons, cashiers, and first-line supervisors—comprise more than half of retail sales employment. In fact, according to the BLS, cashiers and retail salespersons are the two largest occupations in the entire country, employing 7.8 million workers across industries. They are also among the lowest-paid occupations in the economy and more likely to involve part-time or unpredictable scheduling than the management positions held disproportionately by Whites.

Although retail sales employment has been more successfully integrated than management and professional jobs, there remains evidence of occupational segregation among the front-line salesforce. According to our analysis, Black and Latino workers are sorted into the lowest-paid position and away from supervisory roles. First-line supervisors of retail sales workers earn a significantly higher wage than retail salespersons and cashiers, and are more likely to be White. Although 12 percent of all retail sales workers are Black, Black workers make up just over 8 percent of first-line supervisors. Similarly, 13 percent of supervisors are Latino, compared to 15 percent of the retail sales force. As a result just under 1 in 4 Black and Latino retail sales workers report working as a first-line supervisor, compared to more than 1 in 3 White retail sales workers (see Figure 9).

Cashiers, the lowest paid position in the retail sales force, include disproportionately high shares of Black and Latino workers. Over 14 percent of cashiers are Black workers, and 17 percent are Latino. The over-representation in cashier positions amounts to about 1 in 3 workers in the Black and Latino retail sales force, compared to 1 in 4 White retail sales workers employed as cashiers. These results are consistent whether looking at all retail workers or just full-time employees.

Although occupational segregation is not unique to retail, the industry is a leading employer of workers of color and positioned to lead among sectors by instituting changes in hiring, promotion, and compensation that will directly impact millions of workers and reignite our shared commitment to equal opportunity.

The Racial Wage Divide

Black and Latino retail workers earn less than White workers due to both occupational segregation and wage differentials that afford lower pay to Black and Latino sales workers for doing the same jobs as their higher-paid White peers. As one of the greatest sources of employment in the economy today, the inequities in retail perpetuate racial divisions that are reproduced in other markets. Wages lost to the racial earnings divide diminish the ability of workers of color to save, invest, or access the credentials that lead to better jobs. Addressing these unfair compensation practices is a critical piece of inaugurating and embedding equality of opportunity in the American economy today.

The occupation with the highest share of workers—retail salesperson—also exhibits the greatest wage divide. Across race and ethnicity, more than 1 in 3 retail workers in a sales or related position reports working as a retail salesperson, but the differences in compensation are alarmingly varied by racial group. Among full-time workers, retail employers pay the median Black and Latino retail salesperson wages equal to about 75 percent of the pay of the median White salesperson (see Figure 10). For a Black full-time worker that wage divide can amount to more than $7,500 in lost earnings every year.

The second most-prevalent job for Black and Latino sales workers—cashier—also shows a significant wage divide. Retail employers pay all cashiers low wages, so the racial pay distinction is smaller but still significant. Retailers pay Black and Latino cashiers about 91 percent of the wages of White cashiers, a difference between Black and White cashiers of 89 cents per hour, amounting to $1,850 per year.

Across all sales and related positions, retail employers pay Black workers wages equal to 79 percent of the pay of White workers, a difference of more than $3 per hour that accrues to almost $7,000 in lost wages per year. Retail employers pay Latino workers in these jobs wages equal to 80 percent of those of White workers, a difference of $6,400 over the course of a year. As a result of the wage gap and occupational segregation, Black and Latino retail workers are significantly more likely to be low-wage workers than White and Asian retail workers.

The occupational segregation in retail and the wage divide in the most common occupations in the economy translate into a higher prevalence of low-wage employment among Black and Latino retail workers. While retailers pay 58 percent of their full and part-time White workforce less than $15 per hour, they pay about 70 percent of Black and Latino workers wages below that threshold (see Figure 11). This distinction contributes to higher rates of poverty and near-poverty among Black and Latino households.

Scheduling Disparity

Hours on the clock are an important component of retail paychecks, so the unpredictable, unstable scheduling practices common at retailers make workers’ household finances similarly uncertain. In scheduling workers, management exerts control over not only household budgets and living standards, but also workers’ ability to balance their work obligations with other pursuits, like family, education, or a second job. Involuntary part-time work limits the productive capacity of retail workers to contribute to the economy and build a better life. Further complications arise with on-call, unpredictable, and frequently changing schedules, which pose a cost to workers who must clear their non-work calendars and arrange flexible child or elder care and transportation in a scramble for available hours. These problems are intensified for Black and Latino workers who are more likely to be the sole earner in their household, and who must put in more working hours than other retail employees to overcome the racial wage divide.

Part-time employment is prevalent in retail, with 1 in 3 workers on a part-time schedule and the typical retail employee putting in about 31 hours per week. Black, White, and Latino retail workers are equally likely to be working part-time, but compared to other part-time retail workers Black and Latino workers are more likely to want full-time jobs (see Figure 12). These involuntary part-time workers are an exceptionally large share of the Black and Latino retail workforce. More than 40 percent of Black and Latino part-time retail workers would like full-time work but cannot get it during one or more weeks per year, compared to 29 percent of White part-time employees. In the overall retail labor force, 1 out of every 5 Black workers is involuntarily part-time at some point during the year.

These estimates show a significant disadvantage for workers of color in scheduling but are still only part of the picture. The measure does not include workers who want part-time schedules, but still work fewer hours than they would like. For example, a student who needs 25 hours on the clock to pay tuition but obtains only 15 hours per week is not counted as involuntarily part-time. As a result the numbers understate the degree of underemployment in retail.

Access to sufficient hours is just one dimension of the struggle to make ends meet on a retail paycheck. On-call, unstable, and unpredictable scheduling practices are part of the trend called “just-in-time scheduling” creating further problems for the retail workforce and in particular workers of color. Retailers use just-in-time scheduling to increase the flexibility of their workforce and target staffing to variations in customer traffic. This demand for flexibility translates to greater uncertainty for workers who devote more and more resources to employment, often without compensation, and shifts the risks associated with running a retail business from the owners and management onto employees.

Just-in-time scheduling practices impose monetary costs and opportunity costs on workers, and can be a significantly destabilizing factor in the lives of working families. On-call workers are forced to forego other ways of spending their non-working hours, and inconsistent scheduling makes planning for the future, enrolling in classes, securing childcare, and working multiple jobs more difficult. For the one-third of retail workers who are parents, child care arrangements may not be as flexible as a retail shift. In those circumstances working parents take the risk of either paying for child care during on-call shifts for which they may not be paid, or else rushing to find care in the event they are called in to work. Moreover, when hours fluctuate week-to-week paychecks can vary acutely, making it impossible for retail workers to plan a household budget.

Although just-in-time scheduling can have negative effects for any retail worker, there is reason to believe that the burden is disproportionately heavy on Black and Latino workers. Since Black and Latino workers are more likely to be the sole earner in their households, they are less likely to have a stable income from another household member to smooth out finances in the face of unpredictable hours. Occupational segregation and the racial wage divide leave a higher portion of Black and Latino workers in poverty, less capable of shouldering the costs of erratic scheduling and unlikely to be able to maintain a consistent standard of living, much less save for the future, when paid hours are scarce. Moreover, due to residential segregation and other socioeconomic constraints, Black workers have longer commute times than White workers, leading to greater time and money costs when their shifts are cut short.

Working conditions that require full-time commitment but offer part-time compensation generate new costs and risks associated with retail positions, exacerbate the racial disparities in wages and occupations across the retail labor market, and make it impossible for many retail workers to invest in their or their families’ futures. These jobs are antithetical to the perception that retail employment is a place to begin a career while developing the skills for better opportunities in other sectors—erratic, unstable, and on-call schedules sabotage the kinds of commitments necessary to train or educate oneself into better employment, or to hold down an additional job. As a result, occupational segregation, racial wage disparities, and unstable, unpredictable schedules are undermining the financial security of Black and Latino retail workers and their families.

Raising Up Wages and Schedules

Retailers can lead the economy in a commitment to racial equity with changes that improve job quality for all workers. Black and Latino retail sales workers are disproportionately employed in low-pay positions, and earn median wages lower than their White peers. As a result, lifting up workers at the bottom of the wage distribution will compress the gap between higher-paid White retail workers and their Black and Latino colleagues.

Recently, service-sector workers have organized around a call for $15 per hour and the opportunity for full-time work. That new standard would amount to $31,200 annually or about 60 percent of the median earnings economy-wide for men with full-time, year-round jobs. It would also represent a considerable jump in the standard of living for retail sales workers, pulling up the median wage and thus affecting more than 50 percent of the retail salesforce. Though employers have yet to rally alongside their workers for a raise to $15, previous research from Demos shows that many of the nation’s largest retailers could pay significantly higher wages than they currently offer, without negative implications for their bottom lines. And according to our analysis, the median full-time White retail sales worker already reports earning above the $15 per hour threshold. Though the White median wage would increase with spillover effects from a higher minimum, a substantial raise for earnings at the bottom would push median Black and Latino wages closer to that of Whites.

Workers are organizing for raises today, but pay increases tend to phase in over years to dampen the effects on employers. The city of Seattle, which passed a $15 minimum wage in 2014, will take 7 years to reach the full compliance of all companies under the law. Still, envisioning a $15 minimum wage for retail workers expresses the potential for a business model that recognizes that investments in the labor force have real returns in terms of lower turnover costs, higher consumer demand, and a labor market that provides fair wages and a decent standard of living to those people who are willing to work hard.

If today’s retailers lifted their lowest-earning workers to $15 per hour, the median wages of Black and Latino workers would rise to at least that level. Compared with the current median wage of White full-time retail sales workers, $15.53, the improvements for Black and Latino workers would nearly close the gap for the retail salesforce overall. In addition, raising wages for the lowest-paid retail employees could bring millions of workers and their family members out of poverty or near-poverty and make a real difference in the quality of life of the lowest-paid Black, White, and Latino workers (see Figure 13).

Including the spillover effects of the raise as companies adjust pay for workers above the new minimum, a raise to $15 per hour would impact more than 60 percent of all retail workers, and 70 percent of Black and Latino retail workers. Poverty and near-poverty rates for retail workers would be cut in half. In all, 2.5 million retail workers would see their living standards significantly increase. More than half of the workers brought out of poverty or near-poverty would be White, 16 percent would be Black, and 24 percent would be Latino. But although raising wages for the lowest earners moves retail employment closer to racial parity it is not enough to fully bridge racial income inequality on its own.

The effects of a raise in retail wages on working poverty would be dramatic, but even at current wages retailers could make important changes that would raise living standards for their workforce. Involuntary part-time work is an important factor for many retail workers with inadequate earnings, especially in the Black and Latino labor force. Simply employing those who desire full-time work to their full capacity before hiring new part-time workers would reduce poverty in the retail industry by more than 2 percentage points (see Figure 14). Since Black and Latino workers are more likely to be involuntarily part-time, effects on poverty rates for those groups will be even greater. Making feasible, fair changes to scheduling today could reduce poverty among Black and Latino retail workers by 3 or more percentage points.

But retailers are positioned to go beyond involuntary part-time work to make important changes in scheduling practices that would have positive effects on all workers. Increasing scheduling stability would make it possible for retail workers to count on predictable paychecks and to make arrangements for second jobs, family care responsibilities, and education or training. Reducing the uncertainty around schedules would lower the cost of having a job that falls heavier on Black and Latino retail workers and undermines household financial security for all.

Many large retail employers rely on scheduling software that simplifies the scheduling process and assigns workers according to forecasted customer traffic. Companies use these programs to break down their predicted needs and costs—benefits that could be broadened to include the preferences of workers who need to pick up the kids at the sitter or get to class on time. The improvements in working conditions resulting from these changes would produce broad benefits in return, by reducing turnover and increasing productivity while making retail a place where employees have an equal chance to work with dignity without sacrificing their family, education, or professional goals.

Policy Recommendations

Persistently disparate racial outcomes in employment and earnings across the labor force reveal the failure of markets to advance the racial equality codified into law during the Civil Rights Era and situated at the heart of the American Dream. In the 50 years since the Civil Rights Act, the urgent need for the political and economic inclusion of people of color has not diminished. Only our willingness to address these inequities through organized public commitments has waned. In that time, the employment gap consistently left Black workers out of jobs at twice the rate of Whites, and the earnings divide between Black and White families has gotten worse. In the retail industry, occupational segregation, a racial wage divide, and just-in-time scheduling practices have entrenched racial disparities and undermined the financial security of Black and Latino workers and their families.

Five decades is too long to wait for markets to adapt on their own. Cultivating racial equity in the labor market will require an explicit commitment to stop ignoring racially biased outcomes while stigmatizing those workers who are worst affected by them, carrying the institutions of racism into the 21st century. Retail is one of the largest sources of new employment in the US economy, and the second-largest industry for Black employment in the country. At the same time, the most common occupations—retail salesperson and cashier—show evidence of a racial opportunity divide. These conditions point to an important chance for retail employers to make a real impact on racial inequality by paying living wages and offering stable, adequate hours for all workers.

Retailers are positioned to take the first step toward achieving fair labor market practices by addressing the worst conditions of low-wage employment in the sector. Building on those changes, a shared commitment to racial equity in the public and private sectors can forge a new legacy of opportunity and inclusion.

Raise the federal minimum wage

Retailers like Ikea and The Gap made headlines in 2014 by raising wages for their lowest-paid employees as a strategy for improving customer service and sales revenue, while decreasing the costs of employee turnover. Other companies, like Costco, have successfully and profitably pursued this strategy for years. Yet many jobs in the industry still pay rock-bottom wages, and nearly 1 in 5 retail employees and their families live in or near poverty despite holding down a job.

Raising pay for workers at the bottom of the income distribution will improve living standards for the Black and Latino workers employed in low-wage jobs, and reduce the racial wage gap by compressing lower earners toward the higher median wage earned by Whites. Twenty-nine states have already enacted minimum wages above the federal standard, and federal contract workers received a boost to a $10.10 minimum last year. But Congress has failed to act in concert, allowing the real value of the federal minimum wage to erode over time and decreasing living standards among the most vulnerable workers.

If the federal minimum had maintained its buying power since the Civil Rights Era, it would be worth more than $10.75 today. Our current minimum of $7.25 amounts to just two-thirds of that historical value, and not nearly enough to provide workers with the chance to make the critical investments in their futures that promote long-term stability and economic success.

End employment credit checks

Retail employers often evaluate the credit histories of job candidates as part of their hiring decisions, but this practice is likely to have discriminatory effects on people of color without providing insights into whether or not a worker is suited for the job. At the same time, Black workers are more likely to have blemishes on their credit history than White workers because the constraints of high unemployment, low wages, discrimination in credit markets, and a historic and growing racial wealth gap translate to greater economic hardship among people of color.

As a result of the racial and income biases in credit histories, employment credit checks present an unnecessary barrier to employment among Black and Latino workers. Retailers could voluntarily retire the practice of employment credit checks, and should, since there is no evidence linking credit history to trustworthiness or job performance. But inaction on their part despite evidence that the checks are inappropriate and ineffective begs a policy remedy. Ten states have already passed such legislation, and in 2013 Senator Elizabeth Warren sponsored the Equal Employment for All Act, a federal law establishing uniform restrictions on credit checks for employment. Passing this bill would eliminate the worst instances of this racially discriminatory practice and move the US closer to an equal opportunity economy.

Full Employment For All

Full employment targets like those used to inform monetary policy by the Federal Reserve leave Black and Latino workers facing recessionary unemployment rates even during the best economic times. When official unemployment rates dropped to a 30-year low back in 2000, Black workers still experienced 7.6 percent unemployment—more than double the 3.5 percent unemployment rate of White workers and a level that receives voluminous public attention when confronted by the White population. In 2014 as the Federal Reserve considered policy that would tighten expansionary policy and curb job growth, Black workers averaged unemployment rates higher than 11 percent.

Economic growth has not, on its own, propelled full employment for Black or Latino workers in the labor market. In order to achieve full employment for all, broader federal employment policy through the Federal Reserve must be complemented with targeted jobs programs for the communities most affected by joblessness throughout the business cycle. Such a program would address the needs of Black and Latino workers as well as young adults, who have proven unlikely to reach full employment rates comparable to Whites even over long periods of economic expansion. In addition to creating opportunities, such programs have the potential to provide for essential services and contribute to lasting improvements in quality of life.

Protect the rights of part-time workers

In the wake of the Great Recession, service sector job growth called new attention to the poor quality and lack of security that often marks part-time employment in the retail industry. While some employers voluntarily—or as a result of public pressure—adopted fair scheduling systems, many of the country’s largest employing retailers still rely on just-in-time scheduling practices that destabilize households and leave workers in poverty. Legislators in the US House of Representatives, the Senate, and at the municipal level responded to these trends with proposals to address the unmet needs of retail employment and to constrain the most abusive scheduling practices affecting workers today. Among them, The Schedules that Work Act (HR 5159) in the US House of Representatives and Senate, The Part-Time Workers Bill of Rights (HR 675) in the House, and San Francisco’s Retail Workers’ Bill of Rights, provide protections for all retail workers while encompassing the part-time and just-in-time scheduling issues that exacerbate racial disparities in retail.

San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors unanimously approved the Retail Workers’ Bill of Rights in November 2014. This county-level policy is the first legislation to ensure stable hours and predictable schedules for retail workers, including requirements for 2 weeks of notice for scheduling, pay for work-time spent on-call, and provisions to reduce involuntary part-time work. By addressing the worst abuses of just-in-time scheduling, the ‘Bill of Rights’ reduces the opportunity cost of holding a job and restores retail workers’ capacity to control their household finances. At the same time, by addressing the worst obstacles to secure retail employment, the ‘Bill of Rights’ will encourage employee retention and productivity, reducing the cost of employee turnover for the firm.

Make sure Black and Latino retail workers’ voices are heard

New models of worker organization have emboldened service sector employees to speak out for labor protections that have been historically difficult to achieve in service-providing jobs. Yet the resulting changes in job quality and stability have been largely enacted through policy or post-facto lawsuits identifying wage theft or abusive practices only after the damage is done. When workers organize proactively and have a meaningful voice in the workplace, the benefits include greater stability for workers, but also improved productivity for employers and broadly shared economic gains.

A recent study from the Center for Economic Policy Research shows that unionized Black workers earn better wages and benefits than their non-union counterparts, even in low-wage occupations like cashiers. As an elemental facet of the Civil Rights Movement, unions have been a historically important avenue for Black workers to achieve respect and fair treatment on the job. But over the past generation, policies undermining the workers’ ability to organize and advocate for improved working conditions has driven union membership to new lows while benefits and job security became increasingly scarce. Restoring the rights of workers for unionization and collective bargaining has the potential to reverse that trend, and to protect another generation from backsliding living standards.