Accountability Gaps: When Government Inaction Silences Black and Brown Voters

Missing voters aren't missing at all. Many are actually being silenced by bureaucratic barriers and unnecessary logistical hurdles.

Nearly every decision is an economic one when money is consistently low. This stands even for something as basic as the act of voting. The mental gymnastics tend to go something like this:

They’re telling me I need to vote. I’ve got so much else to worry about, I haven’t really thought much about it. Can I do it without losing time from one of my shifts? How far is the voting place? Something’s wrong with my car; do I even have enough gas to make it there and back? Wait—I need that gas to get to work... I can’t cut into the grocery money, even to take a train or bus—which means I can’t afford to bring my kids with me. Who can watch the kids? I forgot that I’m already stretching my gas to make it to the basketball game and band concert and girl scout things this week and next—hold up—have I even fixed my registration since we moved? Who do I find or where do I go to figure this out? When did I need to do this by—can I still fix it or am I too late? That’s more gas money and time off work. And I still have to make sure I have enough for the rent, light and phone bills... I barely keep up with them as it is.

[P]otential voters are understandably not as focused on the 2020 election cycle as they are on the next utility or rent payment, next meal or personal health.

Despite the massive media attention, potential voters are understandably not as focused on the 2020 election cycle as they are on the next utility or rent payment, next meal or personal health. Demos and its partners serve within a number of communities where these more immediate needs take priority. Knowing this, the right to vote becomes even more important to protect, and wherever possible, ensure that public officials fulfill duty to facilitate the process of participation.

Low-income communities of color often suffer the deepest impacts of voter suppression tactics, which further heighten the urgency to have multiple options to register and vote. Those who end up not voting, deterred by all of the hurdles that functionally silence their participation, face the unfair yet ever-present specter of brow-beating by pundits and even those within their own communities.

This characterization centers personal responsibility tropes in ways that ignore the impact of barriers that obstruct full voter engagement.

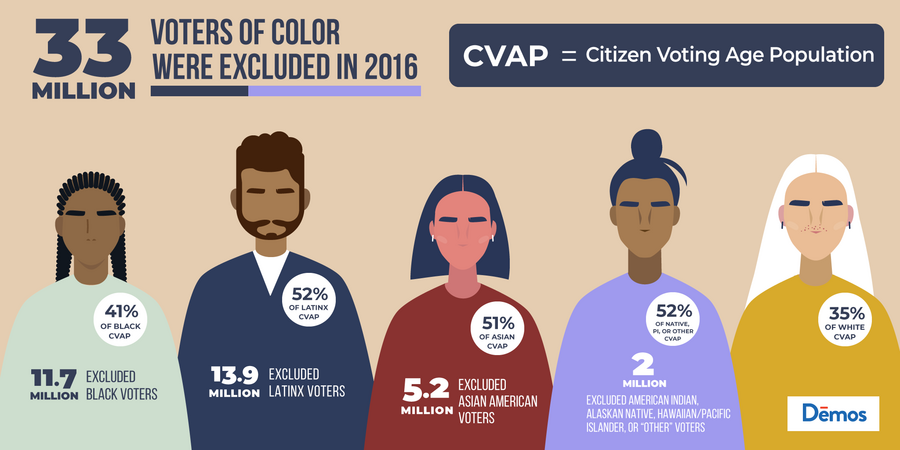

Struggles unrecognized, many eligible low-income voters of color—a major faction among the over 60 million folks whose votes were not cast in 2016, according to internal Demos analysis—will become haphazardly derided as “missing” voters, collapsed into the masses of supposedly disaffected Americans who lack faith in government and voting by extension. This characterization centers personal responsibility tropes in ways that ignore the impact of barriers that obstruct full voter engagement.

These potential voters are not missing. They are not skirting their responsibilities, despite what many critics say. In the past and right now, they labor harder than most to get to the polls, and often do so despite the fact that few elected officials actually listen and act favorably on their behalf. In the next 7 weeks these potential voters, having safer options closed off to them, will literally risk their lives and health to submit their ballots for a general election that once again is being called the most important in this nation’s history.

These factors, not individual discipline, obstruct electoral participation and create a set of silenced voters within the electorate.

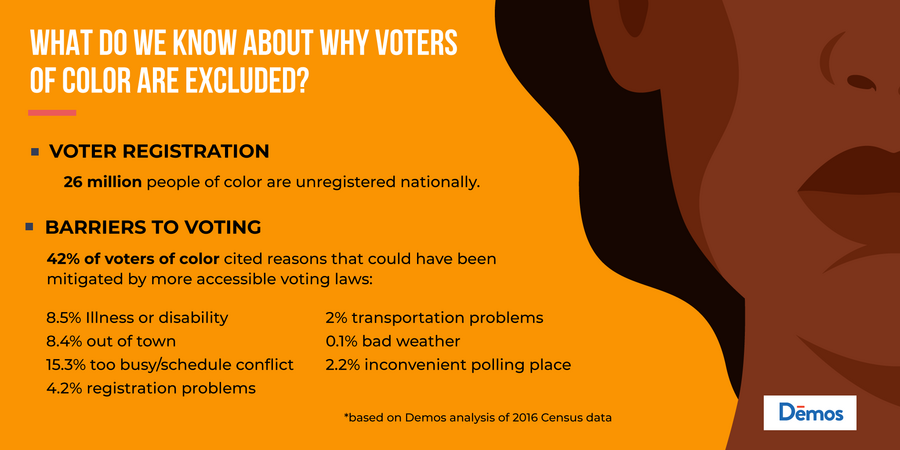

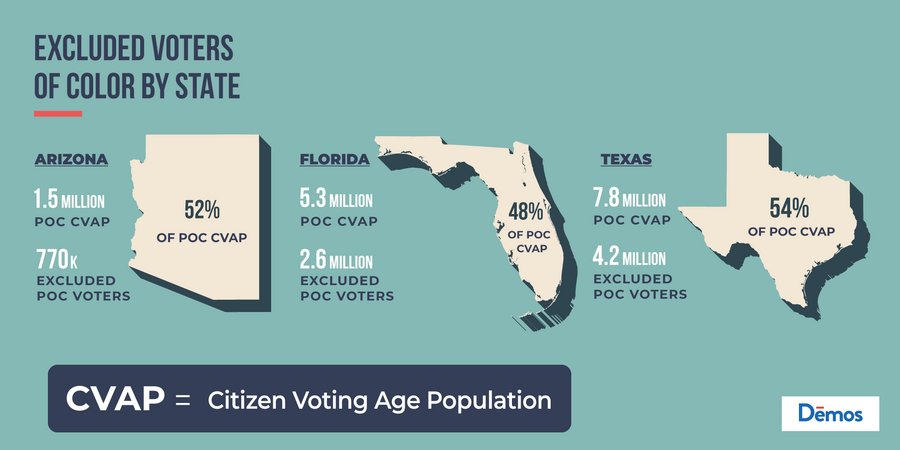

Internal analysis by Demos and partners found that in the 2016 general elections, over 40 percent of eligible voters of color cited the following factors as preventing them from casting a ballot: inconvenient polling locations, transportation issues, and voter registration headaches, among others. Similarly, internal 2018 midterm elections analysis by the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center uncovered that across the same demographics, reasons for not voting included “had a hard time getting away from work and family responsibilities,” “worried someone would try to prevent me from voting,” “not sure where to vote/location of polling place,” “didn’t have or understand the ID needed to vote,” and “targeted by voter intimidation.” These factors, not individual discipline, obstruct electoral participation and create a set of silenced voters within the electorate.

Left without viable alternatives, many voters face 2 fraught options: risk their health and safety to register and/or vote in person, or not participate at all.

Given the vast number of silenced voters, third-party voter registration drives play a crucial role, as they allow community and civic organizations in particular to sign up potential voters by engaging them in person within their neighborhoods: the local grocery store, school event, public forum or even movie theater. Census data shows that eligible Black and Latinx voters registered through third-party programs at rates 3 to 5 times higher than whites in both 2016 and 2018. However, today’s COVID-19 challenges severely limit the ability of organizations to conduct their usual levels of community engagement—levels that persist despite the numerous legal and procedural hassles that generally impede registration drives. Left without viable alternatives, many voters face 2 fraught options: risk their health and safety to register and/or vote in person, or not participate at all. This is unacceptable.

For vulnerable voters who receive Medicaid and/or SNAP benefits, mechanisms are already in place to ease the process of voter registration. The 1993 National Voter Registration Act established that certain eligible recipients—whose numbers increased once COVID-19 took a foothold in the United States—must receive mailed registration forms and related notices that clarify the availability of voter registration when transactions happen through either agency, including during any processes that extend or automatically renew certain folks’ eligibility periods. Given that Black and Latinx recipients access voter registration through these offices in higher proportions than whites, the resources provided factor greatly into reducing the pool of silenced voters.

The problem is that, as of this writing, many states are failing to meet their obligations. The earliest voter registration deadlines are rapidly approaching. North Carolina began accepting ballots on September 4; one-third of the states will do so by early October. Add to this the ongoing U.S. Postal Service drama currently bottlenecking timely mail delivery across the country, and it becomes easy to see how election turnout decisions shift from a matter of convenience to one of safety.

The effort to vote demands jumping through too many hoops, and those hoops carry too high a material and mental cost.

The nation’s current crises make the point more obvious, since a greater percentage of the public faces circumstances that force these issues into the broader conversation. But for those who chronically deal with these economic barriers, the trouble has always been clear. The effort to vote demands jumping through too many hoops, and those hoops carry too high a material and mental cost. To state bluntly: when state elections offices and public assistance agencies do not hold up their responsibilities to proactively protect the vote for Black and brown communities—no matter whether the failures stem from neglect or happen by design—this amounts to voter suppression and structural racism.

Luckily, states still have time to act, and there is a blueprint for changing these circumstances. Demos has found success appealing to election officials in North Carolina, reminding them of their obligations to ensure that voter registration access is properly delivered when any Medicaid eligibility extension or automated benefits renewal process occurs. The state’s Board of Elections promptly moved to ensure full compliance, which will save affected voters not only the ballot, but hopefully some peace of mind also. Timely delivery of notifications and forms to recipients will also help combat potential disinformation campaigns happening in the state. This work can lighten the load for voter registration and Get Out the Vote efforts, the goal being to help even more voters add their ballots to those of the nearly 10,000 voters who quickly submitted their ballots in just the first 7 days. It is imperative to take action now, particularly as voters are already encountering problems, and both advocates and voters know from past elections what will happen if we fail to act.