State and Local Language Access Provisions

State and local language access policies are crucial for ensuring that voters can cast a ballot in a language they understand.

Critically, they can expand language access to voters who have no protection under federal law—namely, communities that are categorically excluded from the Voting Rights Act’s coverage or are too small to satisfy population thresholds for coverage.

State and local governments are well positioned to understand and tailor their policies to address the unique language needs of their constituents. Moreover, even policies that do not expand coverage in any way give local and state leaders the opportunity to reinforce federal language access requirements, as well as affirm the importance of language access in removing barriers to political participation.

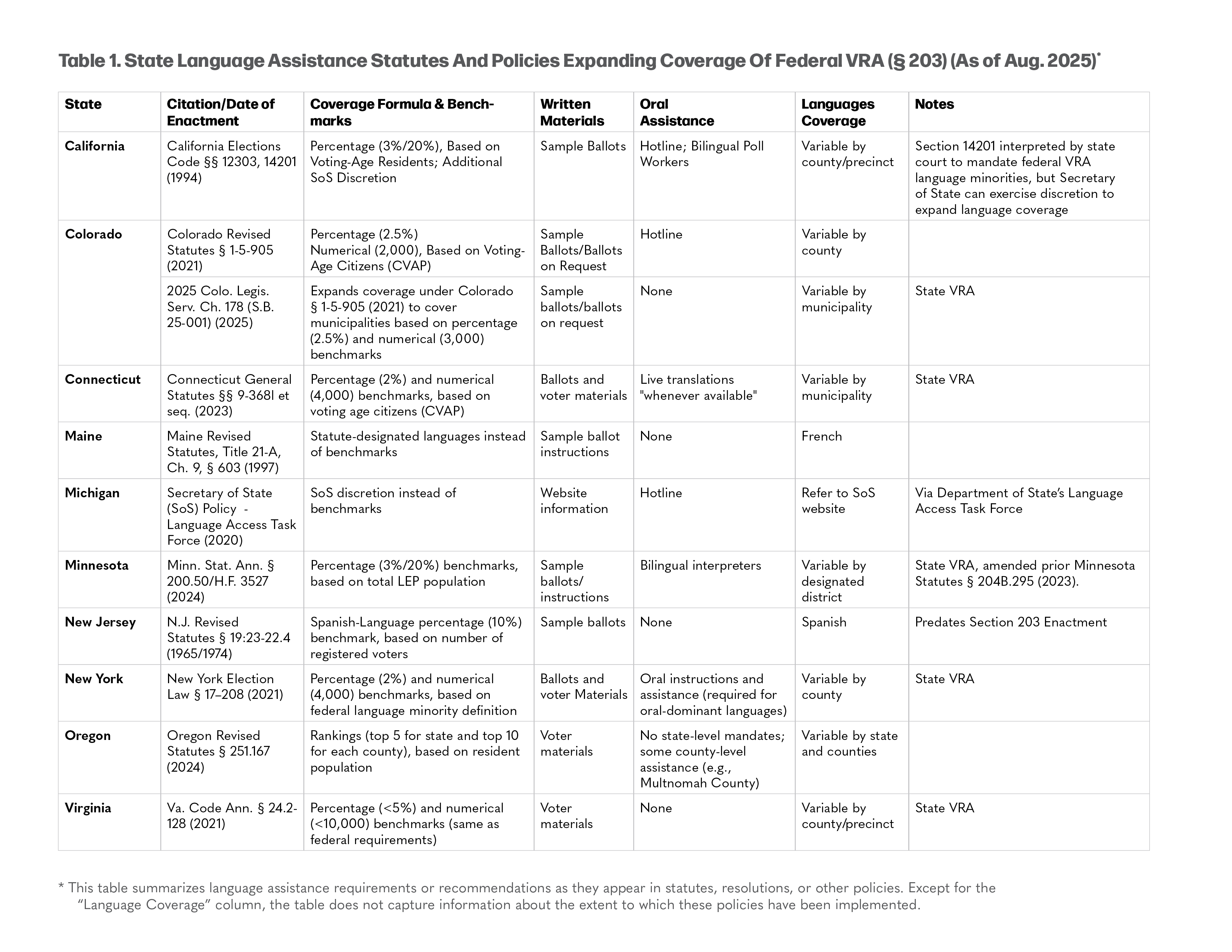

State and local language access policies vary across key elements, including:

- Levels of Government: Policies can be enacted at the state, county, city, or town level.

- Forms of Policies: Policies can take different forms, including state statutes, local ordinances, or election officials’ guidelines or informal rules. The form of the policy can impact its legal force.

- Officials Responsible: Different officials who may be responsible for implementing or enforcing language access policies include chief election officers, state attorneys general, county attorneys, or some combination.

- Required vs. Discretionary Provision of Language Assistance: Policies can require language assistance; make the provision of language assistance discretionary; or be a combination of the two.

- Coverage Determination: Language access policies require jurisdictions to make decisions about which and how many languages to cover. Some policies explicitly name the covered languages while others, similar to the federal VRA, include population-based formulas that trigger coverage. Policies with coverage formulas often set thresholds below the federal thresholds, thus expanding the number of voters receiving assistance.

- Updates and Redeterminations: Policies will generally address how and when, if at all, coverage is reevaluated. The federal VRA requires coverage determinations every five years, but some state and local policies require more frequent reevaluations.

- Eligible Language Groups: Some state and local policies extend eligibility for protections to language groups that fall outside the formal definition of "language minority" under the VRA. For example, states and localities have extended electoral assistance to speakers of languages such as Arabic, Armenian, Farsi, French, Haitian Creole, Polish, Russian, Somali, and Ukrainian.

- Type and Scope of Language Assistance: Policies can vary widely in the type and scope of language assistance provided to voters. Some policies follow the federal VRA’s approach of requiring all election communications and materials to be translated into covered languages while others may be much more limited. For example, some jurisdictions offer translations of only sample ballots, not the official ballot. Additionally, some policies may offer only translated written materials while not providing any oral interpretive services.

- Community Engagement: Some policies require or encourage outreach to and input from affected language groups. For example, a policy might include a provision that requires the creation of a community-based language advisory council.

Language assistance laws and policies across the country fall into three main groups:

1. Laws and Policies Complying or Consistent with the Federal VRA

These often provide another level of enforcement of Section 203 requirements, even if they do not increase language assistance. For example, Rhode Island has Spanish-language coverage for three cities under the 2021 Section 203 determinations: Central Falls, Pawtucket, and Providence. To ensure compliance in broad terms, the state enacted legislation in 2001 that mirrors the triggering formula language in the federal VRA and also includes a specific section providing for bilingual poll workers.1 Louisiana has a similar law that affirms the need to comply with federal language assistance mandates, even though no jurisdictions in Louisiana are currently covered by Section 203.2 Other policies might contain aspirational language that could in theory expand forms of language assistance or broaden language-group eligibility, but do not impose formal requirements on state or local government.

2. Laws and Policies Expanding Federal Standards To Remedy Discrimination

These primarily aim to remedy language-based discrimination. They rely on the basic Section 203 coverage model but change the eligibility for language groups in some way. Some laws at the state level use alternative definitions of language minority groups to extend eligibility to communities excluded from Section 203. Other laws expand assistance for LEP voters by simply lowering the federal benchmarks.

For example, the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act of New York (NYVRA) has language access provisions that apply to political subdivisions in New York state and significantly lower the benchmarks for coverage from those laid out in Section 203.3 The NYVRA omits the federal law’s illiteracy requirement and applies coverage to political subdivisions in the following situations:

- more than two percent, but in no instance fewer than three hundred individuals, of the citizens of voting age of a political subdivision are members of a single language-minority group and are LEP;

- more than four thousand of the citizens of voting age of a political subdivision are members of a single language-minority group and are LEP; or

- for political subdivisions that contains any part of a Native American reservation, more than two percent of the Native American citizens of voting age within the Native American reservation are members of a single language-minority group and are limited English proficient.

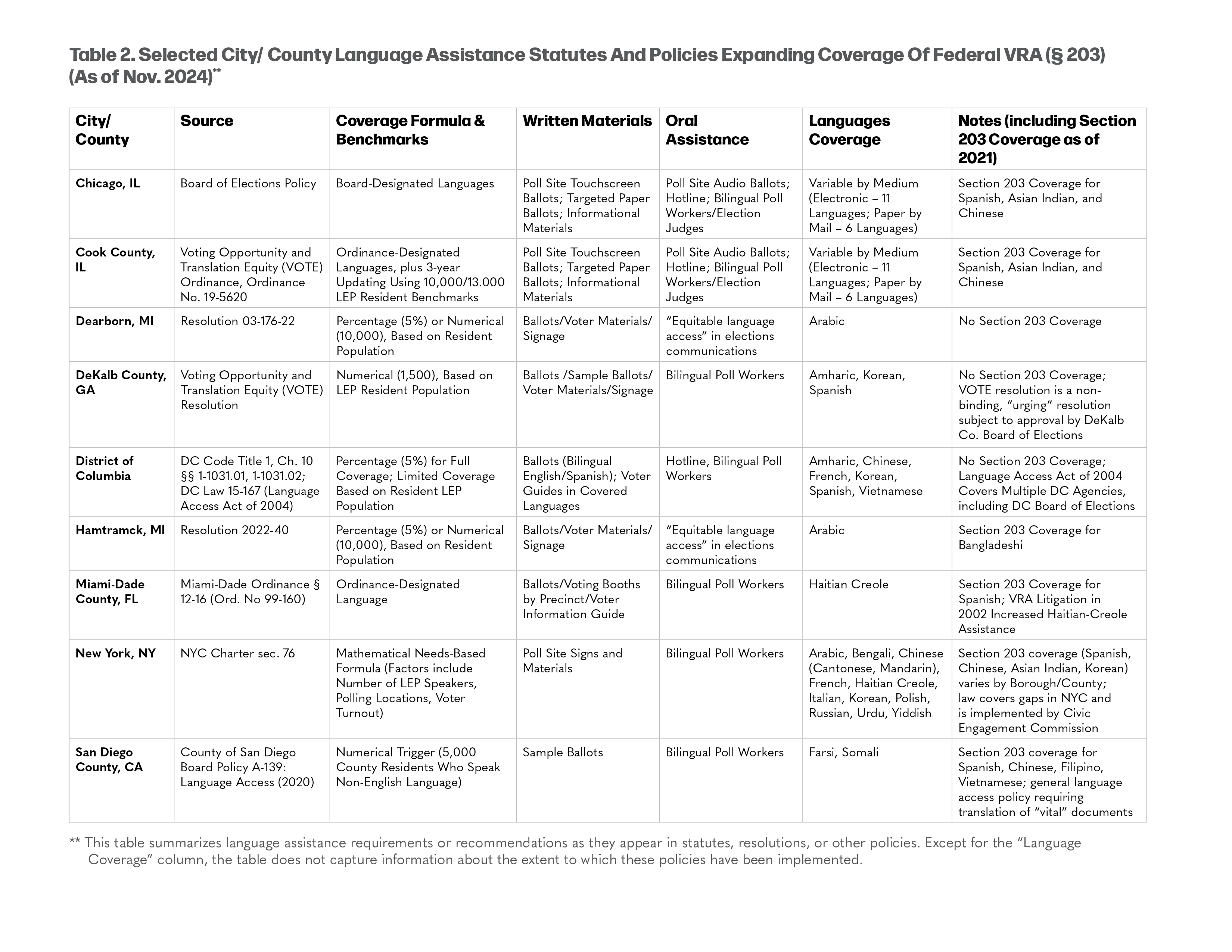

3. Laws and Policies Expanding Federal Standards To Increase Participation

Many recently enacted state and local laws depart from the federal VRA and other policies that use the core VRA framework in one major way: their goal is to increase participation, not just remedy discrimination. These laws expand coverage and seek to broaden political participation by LEP, immigrant, and indigenous populations. Municipal laws tend to be more attuned to local demographics and advocacy and have created systems for election officials to assess how coverage should be extended. These can include developing rankings and prioritizing the largest LEP groups (e.g., top five languages) or creating systems of periodic review to measure needs and add new languages.

For instance, the Cook County, Illinois, Voting Opportunity and Translation Equity (VOTE) ordinance from 2019 contains a preamble that discusses the limitations of the federal VRA, the extent of needs within the county, and the gaps in coverage for LEP voters. The preamble also specifically references research suggesting that civic engagement is a significant predictor of economic opportunity across states and showing that translated voting materials and targeted outreach can help improve voter turnout. It goes on to create mechanisms that implement an array of language mandates beyond Section 203 coverage. Using a benchmark of 10,000 limited-English-proficient residents (not voting eligible LEPs), the County added coverage for eight more languages (Polish, Arabic, Russian, Ukrainian, Tagalog, Korean, Gujarati, and Urdu), alongside the three required under section 203 (Spanish, Chinese, and Hindi).

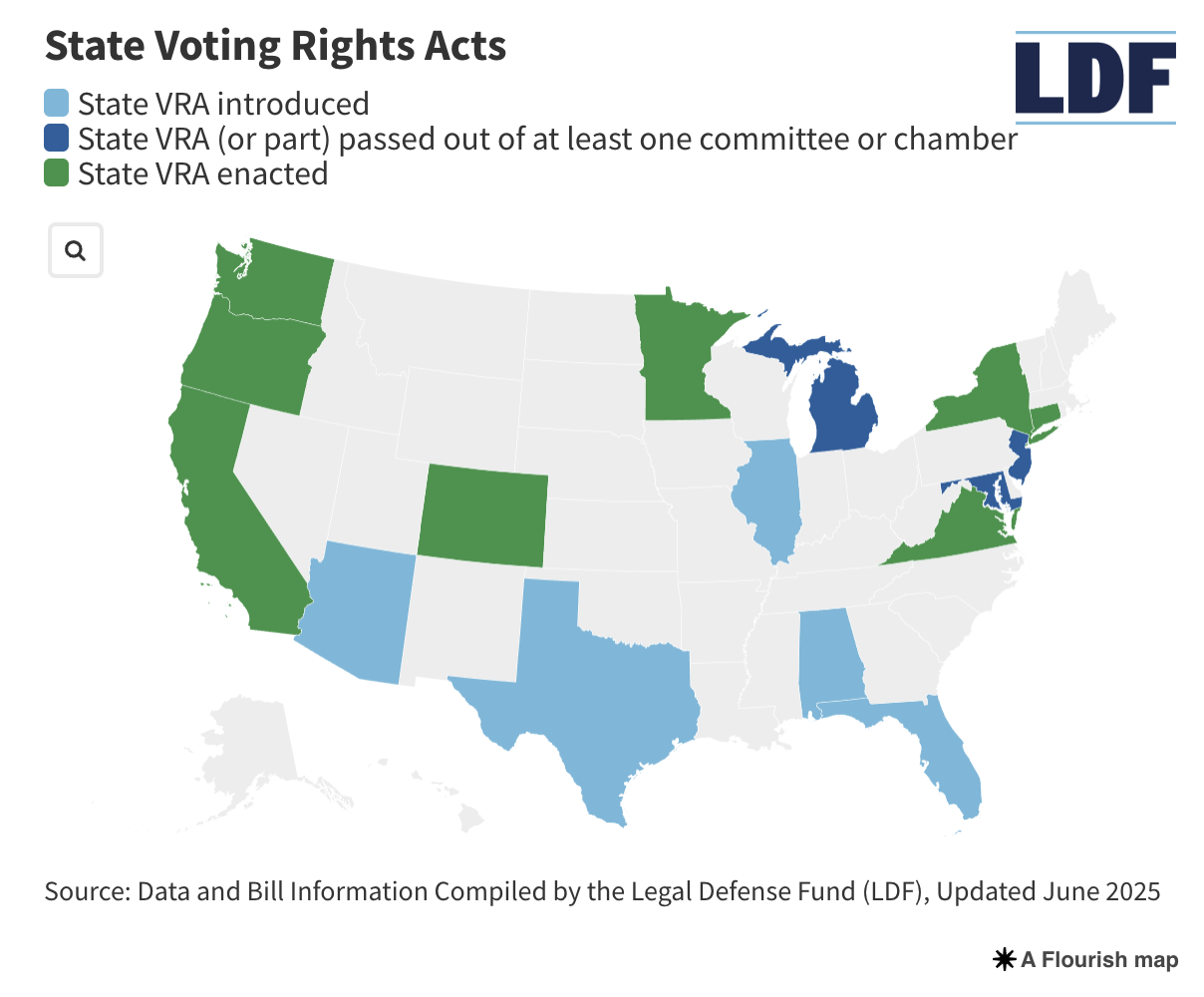

State Voting Rights Acts

In recent years, a growing number of states have enacted their own Voting Rights Acts to supplement the federal Voting Rights Act.

These states include:

- California (2002)

- Washington (2018)

- Oregon (2019)

- Virginia (2021)

- New York (2022)

- Connecticut (2023)

- Minnesota (2024)

- Colorado (2025)

Additionally, as of August 2025, a few other states are close to enacting similar laws, including Maryland, Michigan, and New Jersey.

Many recently enacted state VRAs are expansive in what they cover. They often incorporate protections similar to those that originated in the federal VRA but have been rolled back or questioned by federal courts in recent years.

State VRAs offer state lawmakers an opportunity to expand or build on the language assistance provisions in the federal VRA.

- Typically, state VRA language access provisions draw on the definitions and triggering mechanisms of the federal VRA to offer coverage for language-minority groups.

- They often lower the federal numerical and percentage-based triggers for a language group to get language assistance. How much they lower these triggers is an important policy question that leads to significant variation across states that have enacted VRAs.

For more information about State Voting Rights Acts, see the Legal Defense Fund's resource page