Our nation is on the brink of a retirement crisis that could have severe consequences for both future retirees and society as a whole. The steady erosion in the voluntary employer-sponsored retirement system has made it more difficult for workers to save for retirement. This crisis will not only impact retirees, but the next generation of workers, who will be left with the tab when federal, state, and local governments are forced to expand to help millions of additional elderly Americans who will be living in poverty.1

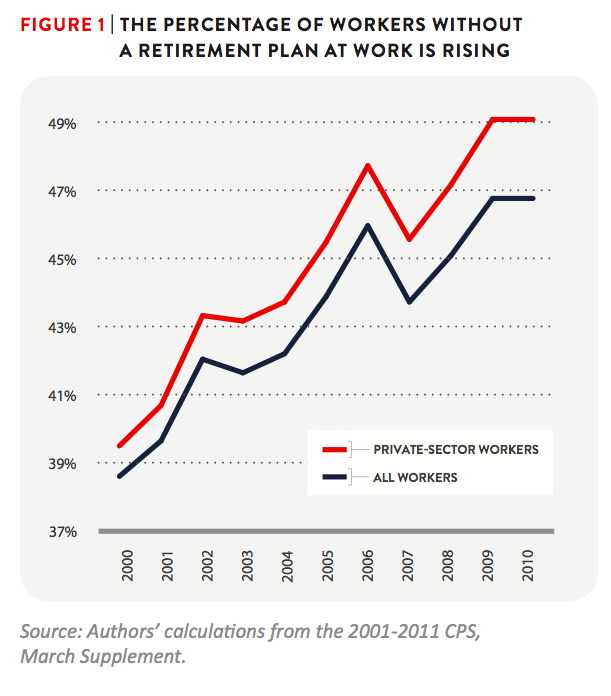

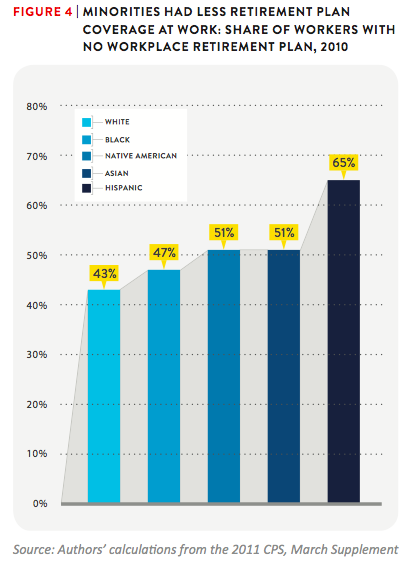

Since World War II the share of the workforce with traditional pensions relied on them to supplement Social Security and maintain living standards in retirement. Virtually no retiree with a traditional pension is poor.2 But the employer-sponsored retirement system is on the decline. Over the past decade alone, the percentage of workers whose employer did not sponsor a retirement plan rose from 39 percent to 47 percent—a 21 percent increase.3 Minorities have even less coverage: 65 percent of Hispanics, 51 percent of Asians and Native Americans, and 47 percent of Black workers were not covered by a retirement plan at work in 2010 (see Figure 4 below).4

In some of the most populous states, the share of uncovered workers has risen more dramatically than the national average. This alarming trend is a call to action for state and local policymakers who want to prevent old age hardship by ensuring all workers can invest adequately, efficiently, and safely for their own retirement.

Moreover, even if workers are covered by a retirement plan through their employer, the quality of that coverage has diminished: traditional defined benefit (DB) plans, in which workers were guaranteed payments for life based on years of service and salary, have been replaced by defined contribution (DC) or individual account 401k-type plans. DC plans shift all the risks and costs of retirement savings onto the shoulders of workers: they charge excessive fees that erode a worker’s nest egg by as much as 30 percent5, require workers to choose from a menu of unsuitable investment options chosen by the employer rather than a long-term investment professional, and will be likely exhausted before the end of a worker’s life.

Social Security is the bedrock of our nation’s retirement system but it was never meant to be the sole source of retirement income. The average benefit is $12,100 per year—barely enough to “keep the lights on.” Yet despite its modest benefits, Social Security provides the vast majority (over 80 percent) of income for 40 percent of older Americans today,6 and will continue to do so for future generations of retirees7 unless we make changes to our retirement system.

All workers need a supplemental retirement plan that invests their savings efficiently with low costs, earns a secure and sufficient rate of return, and preserves savings for retirement. Therefore, the policy challenge is to expand access to individual account-based retirement plans and to address the critical failures in the existing system by making a new retirement savings vehicle available that meets three key criteria for retirement income security:

-

Helps workers make adequate retirement account contributions and prevents early withdrawals.

-

Provides low-cost, quality investment vehicles that are professionally managed and helps shield individual workers from investment and market risks.

-

Provides a lifetime guaranteed stream of income at retirement.

Creating a nationwide, individual retirement plan that incorporates the goals of adequate contributions, safe and appropriate investments, and lifetime income, would efficiently and practically solve the upcoming retirement crisis. But if the nation’s policymakers won’t act, each state can tailor the State Guaranteed Retirement Account plan—which meets all of the above criteria for an efficient and adequate retirement savings plan—to meet their unique needs and to secure retirement income for each state’s workforce.

The State GRA

Given the current state of retirement income security in the United States, we propose states offer all workers a voluntary, low-fee, low-risk, retirement plan to help boost savings for retirement.

What is the State GRA?

State Guaranteed Retirement Accounts (State GRAs) are individual “cash balance” accounts where benefits at retirement are based solely on contributions and returns. A cash balance plan is an already-existing type of defined benefit pension plan that incorporates some features of a defined contribution plan. The State GRA’s major features are:

-

Consistent contributions: as in a 401(k)-type plan, workers and/or their employers would contribute at least 3 percent of pay into their individual State GRA.

-

Guaranteed returns: each account would be guaranteed to earn a return of at least 3 percent, or about 1 percent above inflation. This guarantee ensures that funds are protected from the volatility of the stock market; workers do not have to worry about losing a significant portion of their savings right before retirement.

-

Pooled investments: All individual account assets would be invested together in one large pool, with an emphasis on low-risk, long-term gains. Pooling takes advantage of economies of scale and minimizes financial risks.

-

Portable accounts: Individual State GRAs would be portable; the account would automatically move with a worker from job to job, unlike 401(k)s, which are tied to a particular job and difficult to roll over.

- Lifelong retirement income: at retirement, workers would convert all or part of their State GRA balance into an annuity—a guaranteed stream of income for life—to ensure that they do not outlive their savings.

Investment management costs could be minimized by using the already-existing public pension infrastructure to invest the funds. State pension funds, which operate on a not-for-profit basis, have highly skilled, professional investment managers and administrators that are charged with overseeing and investing more than $3.1 trillion in retirement savings.8 In such an arrangement, assets in State GRAs would be kept in a separate investment pool from public pension fund assets.

Why is a State Gra a Better Retirement Plan than a 401(k)?

The 401(k) system is inherently inefficient because it generates high adminis- trative and investment management costs that are ultimately absorbed by the workers themselves.9 401(k)s also expose workers to a host of risks:10

-

Market risk: workers who have 401(k)s risk losing a chunk of their savings in a market downturn, a particularly damaging prospect for workers nearing retirement.

-

Longevity risk: retirees relying on their 401(k) to supplement Social Security may outlive their savings.

-

Investment risk: 401(k)s force workers to manage their own portfolios, which often leads to lower-than-optimal performance for many reasons: workers sell losing investments while holding winning investments, tend to hold undiversified portfolios, are invested in too many high-risk stocks, and generally lack the expertise necessary to earn high returns.11

-

Contribution risk: workers often contribute too little or too inconsistently to their accounts to accumulate a sufficient nest egg. High account fees can exacerbate this problem, taking a big bite out of already-inadequate savings.

- Leakage risk: workers often whittle away their savings by cashing out assets when they change jobs, by borrowing from their 401(k)s, and by making hardship withdrawals from their accounts before retirement.

These risks and costs are an inherent part of the 401(k) system. Thus, reforms like stricter regulations on brokers, disclosure of 401(k) fees, or requiring plan sponsors to offer more lower-cost index funds, would be band-aids; they wouldn’t fix this fundamentally broken system. Fees would still remain high and workers would still be forced to shoulder most of the risks.

On the other hand, the State GRA would encourage workers to save consistently, and their hard-earned savings would be invested in financial vehicles that charge low fees and provide steady returns. At retirement, their nest egg would be converted into a low-cost annuity to ensure that they have a guaranteed stream of income for the rest of their lives.

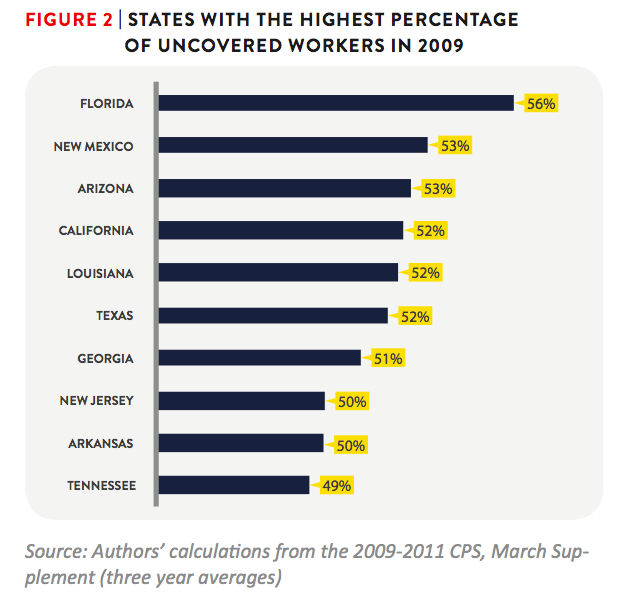

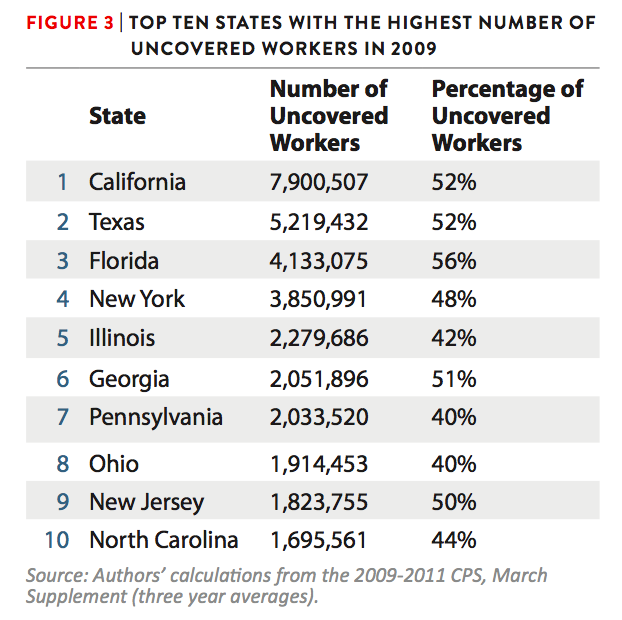

What workers would benefit the most from a State GRA? The workers who would benefit the most from a State GRA are those not offered any type of workplace retirement plan (DB or DC). Nationally, 58.5 million people, or 47 percent of the overall workforce, did not have access to a retirement plan at work in 2010. This is a significant increase from 2000, when 39 percent reported not having access to a workplace plan.12 By state, the percentage of workers who reported not having access to a retirement plan through work ranged anywhere from a high of 56 percent in Florida to a low of 37 percent in Kansas (see Figure 2 above). California has the highest number of uncovered workers—7.9 million—while Wyoming has the lowest at 100,106 (see Figure 3).13

Workers with no plan are disproportionally low or middle-income or of color. Latino workers have particularly low coverage rates: 65 percent are not covered by a work- place retirement plan. Across the workforce, the workers most likely to lack coverage are self-employed or work for small firms. Small employers are less likely to sponsor any kind of plan14 because retirement plans, like health insurance, are a voluntary expense, and because small firms have less time, money, and expertise to navigate regulations and take on the extra administrative burden.

In addition to workers that have no plan, workers who do have a 401(k) plan at work may prefer a supplemental vehicle for their retirement savings that is more secure. By saving in a State GRA, workers can save consistently and invest in financial vehicles that yield steady returns, charge low fees, and minimize investment and market risks.

How Will This Affect Workers’ Ability to Save in 401(k)s?

The State-GRA is a complement—not a replacement—for the 401(k). Workers would still be able to save additional funds in their 401(k). The State GRA allows all workers, particularly low- and middle-income workers and those working for smaller employers, to prepare for retirement. High income workers who have the vast majority of 401(k) assets will likely continue to save additional funds in their 401(k).

Implementation and Oversight

Who Would Oversee and Administer This Plan?

A newly created independent board of trustees would oversee the plans’ operations. The board would assume all fiduciary, or legal, responsibility for the fund’s investment decisions and administration. Fiduciary duty requires all decisions be made entirely for the sole interest of the savers— not the share-holders of the financial service industry— which is a higher standard than the professional standards currently required of 401(k) providers. This also relieves employers, the fiduciaries of their 401(k) plans, of choosing a 401(k) provider and taking on legal exposure to the performance and regulatory compliance of their plans.

The board would likely include the state treasurer, comptroller, and representatives appointed by the governor and state legislature, including stakeholders from the business community and the public at large. The board would delegate investment management to the state pension fund which would bid out actual investment of the funds to private sector investment companies. They would likely contract out the fund’s recordkeeping and participant communications to third parties.

Is Legislation Needed to Implement This Plan?

Yes—legislation would be needed to establish an independent board of trustees and specify guidelines for fund investment, participation, vesting, and benefit accrual. These guidelines would include principles and restrictions concerning how funds are managed and invested, limits on administrative expenses, the length and timing of enrollment periods, employer and employee contribution limits, and payout options, among other details.

Who Is On the Hook If the Fund Becomes Insolvent?

Private insurance contracts would back all assets in the fund. In the unlikely event that there were any shortfalls, private insurers would make up the difference. The insurance premiums would be paid out of State GRA participants’ returns. The cost to insure the plan would be low, since the risk that the fund would fall short of its promised returns would be minimal (see below for a discussion of the fund’s minimal investment risk). Neither the state nor the employer would be held liable or bear any fiduciary responsibility for the fund.

Would the State GRA Comply With Existing Federal Pension Regulations?

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) regulates all private workplace retirement plans. ERISA is a federal law enforced by the Department of Labor (DOL) that requires employer-sponsored retirement plans to meet certain minimum standards regarding participation, vesting, benefit accrual and funding. ERISA also holds plan fiduciaries accountable and requires plans to regularly provide participants with plan information. If a traditional pension plan is terminated because of insolvency, ERISA guarantees payment of certain benefits through the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

Because the State GRA uses employers’ payroll tax system to direct funds, it is essentially a multi-employer plan and would likely be subject to ERISA standards. A State GRA fund would need to cooperate with the DOL to waive employers’ fiduciary liability for the fund’s management. Such a waiver would be a boon for small and mid-size employers who, under the current system, are wary of the extra administrative and legal burden that sponsoring a retirement plan for their employees creates.

Investment of State GRA Funds

Who Would Invest the Funds?

The board of trustees would contract out the fund’s investment and management to the state pension fund(s). States, through their employee pension plans, sponsor excellent financial institutions that, on a not-for-profit basis, get the highest returns for the least cost. In short, because they pool longevity risk, can offer a well-diversified portfolio with longer-term investments, and are professionally managed, public pension funds deliver the same level of benefits as DC plans at only 46 percent of the cost.15 Any funds invested with the state pension fund would be kept in a separate investment pool from public sector funds.

How Are the Funds Invested?

The State GRA aims to shield workers from the high fees and poor investment choices they often face in the retail 401(k) and IRA market (detailed in the “Costs” section below and “State GRA” section above). To provide a low-cost, low-risk alternative to 401(k)s, assets in State GRAs would be professionally invested in one large pool. Pooling assets has a number of significant advantages:

- Professional Investment Management: in the 401(k) system, investment decisions are made by employers and individuals. Pooling individual assets allows investment decisions instead to be made by professional investment managers, who consistently outperform individual investors.16

- Longer-term Investment Horizon: To minimize market risk, 401(k) investors have to shift towards increasingly conservative portfolios as they age, often at the expense of higher potential returns. This tradeoff is costly because it reduces returns the most at a time when workers’ assets are at their peak: when they’re nearing retirement. In contrast, when assets are invested as a pool, there is no need for such a tradeoff. Because new workers are constantly entering the pool as older workers retire, the fund’s investment managers can maximize returns over the long-term, not just over an individual worker’s lifetime.

- Lower Fees: By taking advantage of economies of scale, pooling reduces both investment management and administrative costs. See the section on “Costs” for a more detailed explanation of the State GRA’s investment and administrative fees.

The Guaranteed Rate of Return

What is the Guaranteed Minimum Rate of Return?

The guaranteed minimum rate of return is one of the defining characteristics of the State GRA. It ensures that at retirement, savers receive a benefit that includes the total amount of funds they deposited into their account over their work life plus at least some annual minimum rate of return on their assets.

This minimum guarantee insures workers against the possibility of losing a significant portion of their hard-earned savings during bad economic times while also allowing them to capture higher investment returns when the market is performing well. Even in a year of poor investment returns, participants would be guaranteed at least a 3 percent rate of return on their investments, or 1 percent after adjusting for inflation. However, in high-performing years participants would receive additional returns, projected to be as high as 7 percent (5 percent after adjusting for inflation).17 To enable the fund to meet its 3 percent guarantee in low-earning years, some of the investment earnings in excess of the guarantee would also be deposited into a “rainy day fund”.

This is not a radical idea: TIAA-CREF, one of the largest investment firms in the country, has offered a similar fund, their TIAA Traditional Annuity Fund, to non-profit workers and teachers for over 80 years.

How Is the Rate of Return Determined?

Based on recommendations from the fund’s investment managers, the board of trustees would be responsible for determining whether savers would be eligible for returns above the guarantee in any given year. The annual rate of return would be set with the long-term stability of the fund in mind. In other words, when savers receive their annual account statement in the mail, their balance would reflect their previous balance, plus current contributions, plus the guaranteed 3 percent rate of return on their investment, plus extra returns, if any, as determined by the board.

Is Guaranteeing a Rate of Return Economically Feasible?

Yes. There has never been a 50-year period in which a balanced portfolio split evenly between stocks and bonds has yielded an average annual real return of less than 5.6 percent (3.6 percent after adjusting for inflation).18 Projecting into the future, a similar portfolio is likely to generate an average annual rate of return of 7 percent (5 percent after inflation) over the long term, taking into account a range of scenarios on long-term market performance.19 Moreover, the same simulations predict that there is very little risk of the rate dropping below 4.9 percent over the long term.

This indicates that with widespread participation and regular contributions, the guarantee would pose very little risk for the fund. However, to safeguard against any shortfalls, the fund could take out an insurance policy with either the state or private insurers. Because funds are invested in longer-term assets as one large pool, the costs associated with insuring the minimum guarantee would be inexpensive, and could be absorbed by participants without eating up too much of their nest egg.

How Would Returns Compare to 401(k)s?

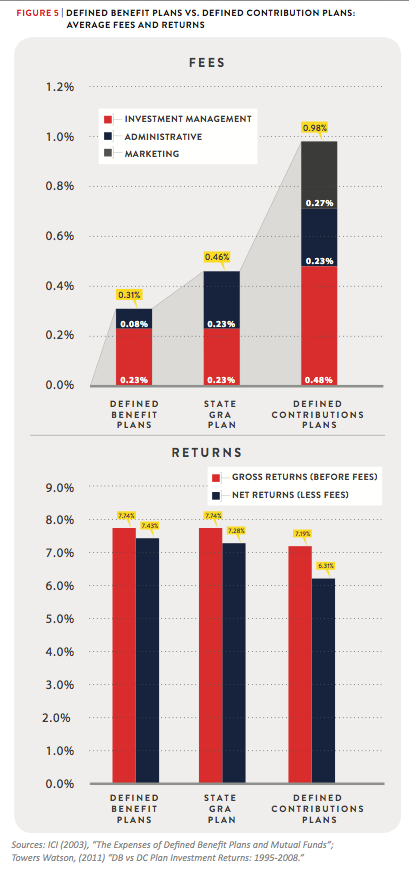

Average returns on State GRA assets would be similar to those earned by traditional DB plans, and would therefore likely outperform 401(k)s by an average of nearly 1 percent per year (see Figure 5). State GRA returns should match average DB returns because their investments are managed in the same fashion: both invest their assets as a pool and seek to maximize long-term returns. As detailed above in the “Investment” section, this is more efficient than the individualized 401(k) invest- ment structure for several reasons, but primarily because of the efficiency of scale and professional investment management. And these efficiencies translate into real performance: studies by Towers Watson20 and CEM Benchmarking21 show that returns for defined benefit plans consistently outperform 401(k) plans by an average of 1.03 percent and 1.8 percent respectively. If State GRA investments follow this trend, higher returns for workers with a State GRA could make a huge difference, over a lifetime of saving, in their retirement security.

Costs

What Are the Costs to Savers? How Are They Assessed?

There are, of course, costs associated with running any kind of retirement plan. These costs can be grouped into three major categories: administrative costs for bookkeeping and informing participants of account balances and plan features; investment management costs for investing participants’ savings; and marketing costs for media advertising of the plan’s virtues.22 However, unknown to most retirement savers,23 participants actually pay all or the vast majority of these costs24 through fees charged as a percentage of their account balance and paid out of their investment returns.

Participants in a State GRA would pay its costs in exactly the same way: out of the returns earned by their savings, before their accounts are credited with those returns.

How Do State GRA Costs Compare to 401(K) Fees?

Because the costs of running any retirement plan are paid by participants out of their investment returns, minimizing these costs is essential to their retirement security. Overall, the costs of a State GRA should be much lower than the average fees paid by 401(k) participants. Because State GRA funds would be invested in the same fashion as a DB plan (see section on “Investment”), the investment management fees should also be similar, and as shown in Figure 5, therefore lower than typical 401(k) plan investment management fees. Marketing costs, which are often a substantial expense for 401(k) plans, would be much lower as well for a State GRA. However, because State GRAs are individual accounts, their administrative costs would likely be similar to 401(k)s and other individual retirement plans. As shown in Figure 5, the total costs of State GRAs should still be significantly lower than 401(k)s, savings which would be passed on to participants in the form of higher returns.

To Employers? To The State?

The costs to employers and states would be nearly nonexistent. Administrative tasks, such as processing payroll deductions and distributing information to plan participants, would require minimal time investment from employers and states. The monetary costs of running a State GRA would be charged directly to participants, though states or employers could choose to offset some or all of those costs if they wished.

In the short term, states would likely lose some tax revenue by creating a State GRA because contributions would be tax-deductible and State GRAs would likely entice some workers to save earnings that would have otherwise been taxed. However, the long-term cost would likely be much smaller, because increased retirement savings for workers would translate into more retirement income (and more revenue for states) as well as saving states money on social services for the elderly.

Accumulation

Is There A Minimum Yearly Contribution? Minimum Balance?

The prohibitive cost of administering small, static accounts requires that there be minimum annual contributions to the fund. The board of trustees would set this default contribution rate between 2-5 percent of a worker’s salary depending on current market performance and economic conditions. A worker can choose to opt out of the minimum contribution at any time.

Are the Contributions and Accumulated Returns Taxed?

No. As in 401(k)-type plans, contributions are made pre-tax and returns accumulate tax-free.

What is the Maximum Annual Amount Workers Can Contribute?

Tax deductible contributions to a State GRA would have the same limit as a 401(k): $17,000 as of 2012. However, this would be a shared limit: individuals could contribute up to $17,000 between their State GRA and/or their 401(k).

Can Employers Contribute?

Yes, employers would be able to contribute to a worker’s State GRA. However, they would not be required to contribute. Like other contributions to pension plans, employer contributions to the State GRA would be tax deductible. States could also create additional incentives for employer contributions.

Participation

Who is Eligible to Open Up a State GRA? Workers or All Residents?

The simplest option would be to have the fund open only to part- or full-time workers in the private sector. Contributions could be channeled through the already-existing payroll deduction system, reducing the plan’s administrative burden. State governments already make deductions for workers’ compensation insurance from a worker’s paycheck; contributions to a State GRA could be made through that system. Eventually, a State GRA could be open to all residents—including employees of very small firms and the self-employed—if the state were to create a way, such as an online system, for citizens to contribute to the fund outside of the workplace.

Can an Employee of an Employer Who Sponsers Another Type of Retirement Plan Still Participate?

For State GRAs to be truly portable, all employers in the state (except for very small employers) would be required to offer the State GRA. Employers would still be able to offer a 401(k)-type plan in addition. If employers choose to offer both the State GRA and a 401(k), their employees could contribute to their State GRA, to their employer’s 401(k), or both.

Because State GRA contributions would be made through an existing payroll deduction system, and because, unlike 401(k)s, employers would not be the plan sponsor of the State GRA, the burden of this requirement to employers would be negligible.

Portability and Withdrawals

Is the GRA Portable Between Jobs?

Yes. Unlike a 401(k) it is “fully” portable—no rollovers necessary. With the State GRA, if a worker changes jobs, their account would be automatically accessible from their new employer. In today’s mobile job market, it is unreasonable to require workers to navigate the difficult process of rolling over their retirement savings each time they switch jobs. Full, automatic portability significantly reduces the chance that a worker cashes out their savings before retirement, misses contributions between jobs, fails to enroll in their new employer’s plan, or leaves a long trail behind them of small, stagnant retirement accounts from former employers.25

What Happens to an Individual's Account if They Move to Another State?

The account would stay open and continue accumulating returns, but the worker could no longer contribute through their new (out-of-state) employer. An online system that allows accountholders to contribute outside of the workplace would make it possible for workers to continue contributions to their State GRA if they moved out of the state or were temporarily unemployed or out of the labor force.

Are Loans or Hardship Withdrawals Permitted?

No—State GRA funds are accessible only at retirement. Funds cannot be accessed before retirement for any reason other than death or disability. Eliminating early withdrawals reduces the fund’s liquidity requirements, allowing State GRAs to offer the highest guaranteed rate of return at the lowest possible cost. Limiting or prohibiting early withdrawals also helps ensure adequate retirement income.26 The State GRA is meant to be an adequate supplement to Social Security, one that workers can count on at retirement.

At What Age Can Funds Be Accessed?

Participants would begin collecting retirement benefits at the same time as Social Security, and therefore no earlier than the Social Security Early Retirement Age, i.e. age 62.

Can Funds From a State GRA Be Rolled Over Into a 401(k) and Vice Versa?

Workers with a 401(k)-type plan or IRA could roll over their balances into their State GRA. However, following the same reasoning for prohibiting early withdrawals, transferring State GRA funds into 401(k)-type accounts would also be prohib- ited. Rollovers would be administratively expensive and would defeat the goal of connecting workers’ long term savings to longer-term assets—a necessary condition for guaranteeing secure and adequate returns.

Lifetime Income Options

At Retirement, How Do Workers Access Their State GRA Funds?

At retirement, workers have the option of either converting their entire account balance to an inflation-indexed annuity or receiving a partial lump sum, limited to 10 percent of their balance. These annuities would also provide survivor benefits unless the worker opted out in exchange for a higher single-life annuity.

Must State GRA Participants Annuitize All or Part of their Savings at Retirement?

Yes. An annuity provides a retiree with a guaranteed stream of income for life. A 401(k) allows retirees to receive their entire balance as a lump sum, and as a result, they run a significant risk of outliving their savings. Given the lengthy life expectancies of future retirees and rising medical costs, the risk of outliving one’s saving is very real, and is a threat to both family finances and state budgets. Workers who want more flexible retirement income can still invest in a 401(k)-type account.

Can Workers' Heirs Inherit their State GRA Assets?

Yes. Account balances of participants who die before retirement will be transferred to the State GRA(s) of their designated beneficiaries. Those who die after retirement can leave their remaining State GRA assets to their heirs either as a lump sum or as a (larger) transfer to their own State GRA.

Who Will be the Annuity Providers?

The fund’s board of trustees will chose private-sector providers based on a competitive bidding process. State pension funds could also provide annuities themselves, offering a low cost public option.

Additional Policy Options

Required Employee/Employer Contributions

One option for states would be to require a minimum employer or employee contribution, either as a percentage of the employee’s salary or as a flat minimum amount. This feature would boost savings and make retirement security a shared responsibility between employers and employees.

Tax Credit

A state could also offer a tax credit for contributions to the State GRA. In the current proposal, contributions and investment earnings would accumulate tax-free, for both State GRAs and 401(k)-type plans. These retirement tax breaks amount to a significant loss of tax revenue for federal, state, and local government budgets. At the federal level, tax breaks for retirement accounts will cost taxpayers a staggering $540.6 billion between 2012 and 2017.27 Because most state and local tax codes pass through federal tax deductions, cash-strapped state and local government budgets also suffer a substantial revenue loss from these tax expenditures.28

Unfortunately, these tax breaks fall far short of fulfilling the intended goal of increasing retirement security for most working families. Because this subsidy is in the form of a tax deduction rather than a credit, these expenditures are highly regressive. Taxpayers in the highest tax brackets, who are likely to save without government incentives, receive the largest tax break. Taxpayers with the lowest incomes receive relatively miniscule assistance. For example, in New York City, low-income earners receive an estimated $16 per year, while those in the top brackets receive 28 times more, or over $448 per year.29

Therefore, instead of allowing contributions to the State GRA to be made pre-tax, savers could receive a flat tax credit. The credit should be large enough to refund a low-income worker’s default contribution. In New York State, for example, a family earning a lower-middle class income of $40,000 a year pays 4.9 percent in state taxes. They would normally pay around $250 in state taxes on their maximum $5,000 contribution to their State GRA; thus, a tax credit should be at least this amount. This change would increase the retirement security for all workers without imposing any additional cost on their employers.

A State-Backed Guaranteed Rate of Return

Instead of contracting out the insurance of the minimum guarantee on investments to a private insurance company, the state could back the guarantee. Recent studies agree that the government remains the most secure and lowest cost provider of insurance on guarantees to DC-type plans.30

In addition, the state’s negligible risk from backing a minimum rate of return for retirees is outweighed by the potential economic gains to the state from the increased retirement income security a State GRA plan would provide. Increasing retirement income security delivers enormous economic returns and prevents negative fiscal consequences resulting from a large population of impoverished elderly straining the safety net.

Endnotes

-

Saad-Lessler, Joelle, Teresa Ghilarducci, and Lauren Schmitz. New York’s Retirees: Falling Into Poverty. Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis, February 2012. http://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/guaranteeing-retirement-income/465-new-scepa-study-the-downward- mobility-of-new-yorks-retirees.html.

-

Porell, F., and D. Oakley. “The Pension Factor 2012: Assessing the Role of Defined Benefit Plans in Reducing Elder Hardships” (2012). http:// www.nirsonline.org/storage/nirs/documents/Pension%20Factor%202012/pensionfactor2012_final.pdf.

-

Authors’ calculations from the 2001 and 2011 Current Population Survey (CPS), March Supplement. Data provided by: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), Current Population Survey: Version 3.0. [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010.

-

Authors’ calculations from the 2011 CPS, March Supplement.

-

Hiltonsmith, Robert. The Retirement Savings Drain: The Hidden and Excessive Costs of 401(k)s. Demos, May 29, 2012. http://www.demos.org/publication/retirement-savings-drain-hidden-excessive-costs-401ks.

-

U. S. Social Security Administration, Office of Retirement and Disability Policy. “Income of the Population 55 or Older, 2010 - Importance of Income Sources Relative to Total Income”, 2010. http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/income_pop55/2010/sect08.html#table8.a5.

-

Butrica, Barbara, and Karen Smith. This Is Not Your Parents’ Retirement: Comparing Retirement Income Across Generations, 2011. http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v72n1/v72n1p37.html.

-

As of Q1 2012. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. “Flow of Funds Accounts, Flows and Outstandings: Z1 Statistical Release”, June 7, 2012. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/.

-

Hiltonsmith (2012), op. cit.

-

Hiltonsmith, Robert. The Failure of the 401k: How Individual Retirement Plans Are a Costly Gamble for American Workers. Demos, November 2010. http://www.demos.org/publication/failure-401k-how-individual-retirement-plans-are-costly-gamble-american-workers.

-

Barber, Brad M., and Terrance Odean. “The Behavior of Individual Investors.” SSRN eLibrary (September 7, 2011). http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1872211.

-

Authors’ calculations from the 2000 and 2010 CPS, March Supplement.

-

Authors’ calculations from the 2008-2010 CPS, March Supplements. State sponsorship numbers are three-year averages over the period 2008-2010.

-

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employee Benefits in the United States: News Release”, March 2012. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ebs2.nr0.htm.

-

Almeida, Beth, and William Fornia. A Better Bang for the Buck: The Economic Efficiencies of Defined Benefit Pension Plans. National Institute on Retirement Security, August 2008. http://www.nirsonline.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=121&Itemid=48.

-

Barber and Odean, op. cit.

-

Stubbs, David, and Nari Rhee. Can a Publicly Sponsored Retirement Plan For Private Sector Workers Guarantee Benefits at No Risk to the

State?. UC Berkeley Labor Center, August 2012. http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/research/ca_guaranteed_retirement_study.shtml.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Apte, Vishal, and Brendan McFarland. DB Versus DC Plan Investment Returns: The 2008–2009 Update. Towers Watson, March 2012.

-

DC Plans Under Performed DB Funds. CEM Benchmarking, 2006.

-

See Hiltonsmith (2012), “The Retirement Savings Drain,” op. cit., for more information on these costs and their impact on retirement savings.

-

AARP. 401(k) Participants’ Awareness and Understanding of Fees. March 2011. http://www.aarp.org/work/retirement-planning/info-02-2011/401k-fees-awareness-11.html.

-

Rosshirt, Daniel. Inside the Structure of Defined Contribution/401(k) Plan Fees. Deloitte/ICI, November 2011. http://www.ici.org/pressroom/news/11_news_deloitte_401k.

-

Harris, Benjamin, and Rachel Johnson. Economic Effects of Automatic Enrollment in Retirement Accounts. AARP, February 2012.

-

Butrica, Barbara A., Sheila R. Zedlewski, and Philip Issa. Understanding Early Withdrawals from Retirement Accounts. Urban Institute,2010.

-

Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2013: Analytical Perspectives. Office of Management and Budget, 2012. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Analytical_Perspectives.

-

Schmitz and Ghilarducci (citation below) estimate the lost tax revenue to New York City and State from tax preferences for all individual retirement savings plans, including 401(k)s, IRAs, and Keoghs, to be approximately $1.79 billion annually. The cost includes over $390 million for the city and $1.39 billion for the state. To put these numbers in perspective, $390 million is more than the $290 million the city spent on its parks.

-

Schmitz, Lauren, and Teresa Ghilarducci. New York City and State Tax Expenditures for Defined Contribution Plans. Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis, March 2012. http://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/retirement-security.html.

-

Stubbs and Rhee, op. cit.