The steep increase in college tuition and student debt over the past decade has led our country to engage in a serious debate about the need to reduce college costs and student borrowing. Yet many misconceptions remain about the scope or magnitude of the problem that student debt poses to our national economy and student debtors’ financial security.1,2 More than 44 million Americans, or nearly 1 in 5 adults, now carry student debt. That share is even higher among millennials, one-third of whom have student loans.3 And the burden of carrying student debt isn’t borne equally— today more than half of African American households under age 40 have student loan debt.4 Student debt has negative impacts for many borrowers; studies show that student debtors have less savings, more difficulty purchasing homes, and less retirement savings.5 However, student debt is particularly damaging for individuals who struggle to repay their loans: borrowers who are seriously delinquent on their payments or who default on their loans. Delinquent borrowers are saddled with fees, penalties, and rapidly-accumulating interest; borrowers who default on their loans face ruined credit and a debt often several times their original loan balance. Even worse, they cannot even turn to bankruptcy for relief from their loans, unlike most other kinds of debt, and face a debt collection process that is often punitive and draconian.6

In fact, nearly 40 percent of student loan borrowers are either in default or more than 90 days past due on their student loan payments. And importantly, the majority of people struggling to pay back their college loans have relatively small amounts of debt; half owe less than $16,400. This belies the common media portrayal of struggling borrowers as carrying excessive amounts of debt beyond the average, and brings into question whether a higher education system financed primarily by debt is putting undue risk on students trying to build skills and climb the economic ladder. And it isn’t just borrowers who didn’t earn degrees who are struggling to repay their loans; in fact, a quarter of borrowers with bachelor’s degrees are in default or seriously delinquent on their loans. In this brief, we use data from Experian, one of the three major credit rating bureaus in the United States. Our analysis examines the repayment status of student loan borrowers, analyzing the nature of student loan defaults and delinquencies, and the role of student loan balances on an individual’s overall financial security. As the brief shows, there is no “safe” amount of student debt: borrowers with small balances struggle to repay them at the same rate as borrowers with higher balances. That’s why this brief concludes with a series of policy reforms to address the underlying causes of rising student loan debt and the very real struggles millions face in repaying their loans.

KEY FINDINGS

- A large share of borrowers struggle to repay their loans. Nearly 40 percent of student loan borrowers in repayment are either in default or more than 90 days past due on their student loan payments.

- The average borrower in default owes no more than the average borrower who is current on their loan payments. The median student loan balance among borrowers in default is $16,381, slightly higher than the median balance of borrowers who are current on their payments, $15,654.

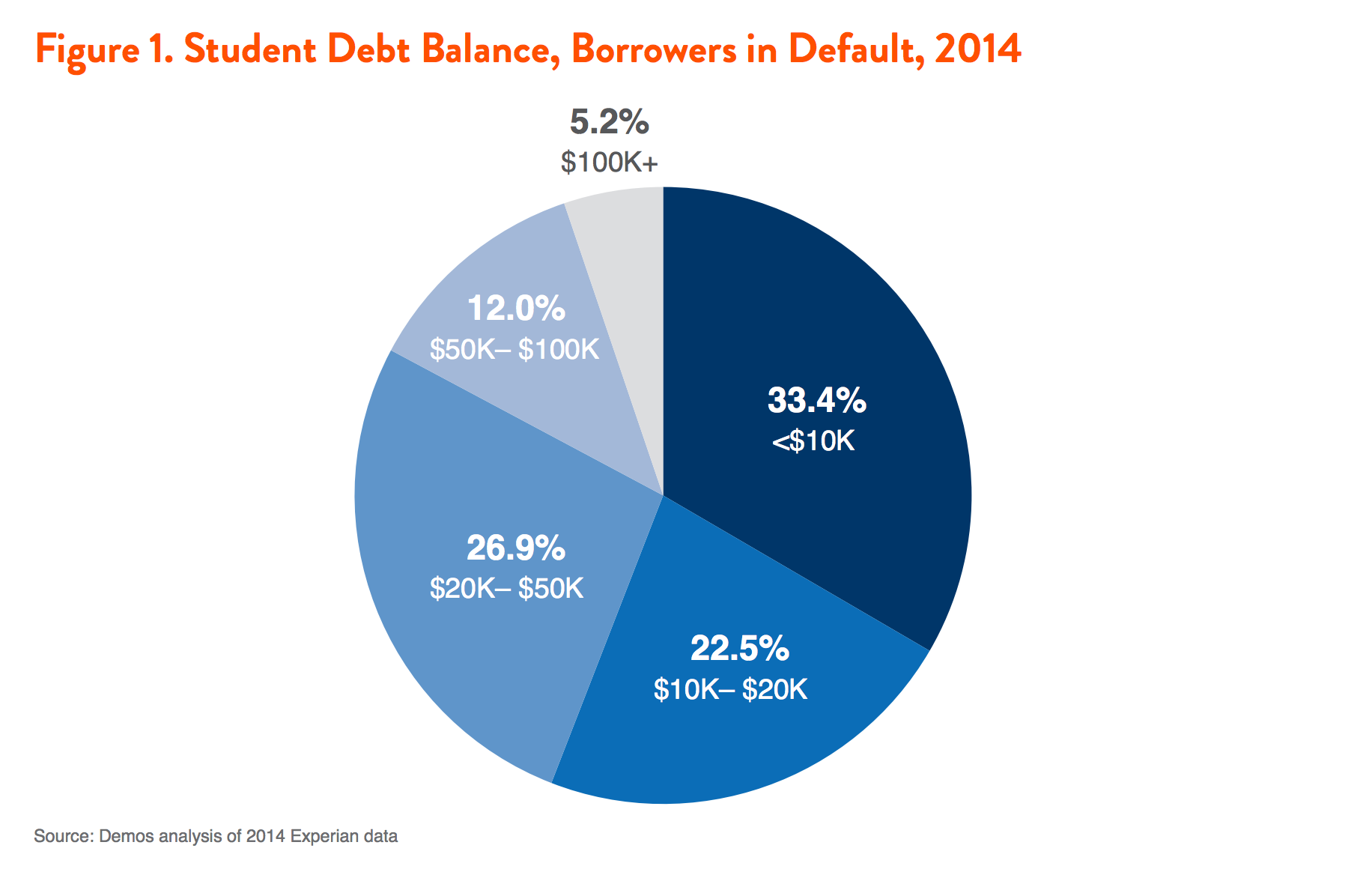

- Most borrowers in default owe small amounts. A third of borrowers in default owed less than $10,000 in 2014, and 56 percent owed less than $20,000.

- Default is essentially unrelated to the amount borrowed. Borrowers with the smallest balances—those with less than $10,000 in student debt—defaulted on their student loans at almost the exact same rate as borrowers with the largest balances—more than $100,000 in debt; their default rates were 13 percent and 14 percent, respectively.

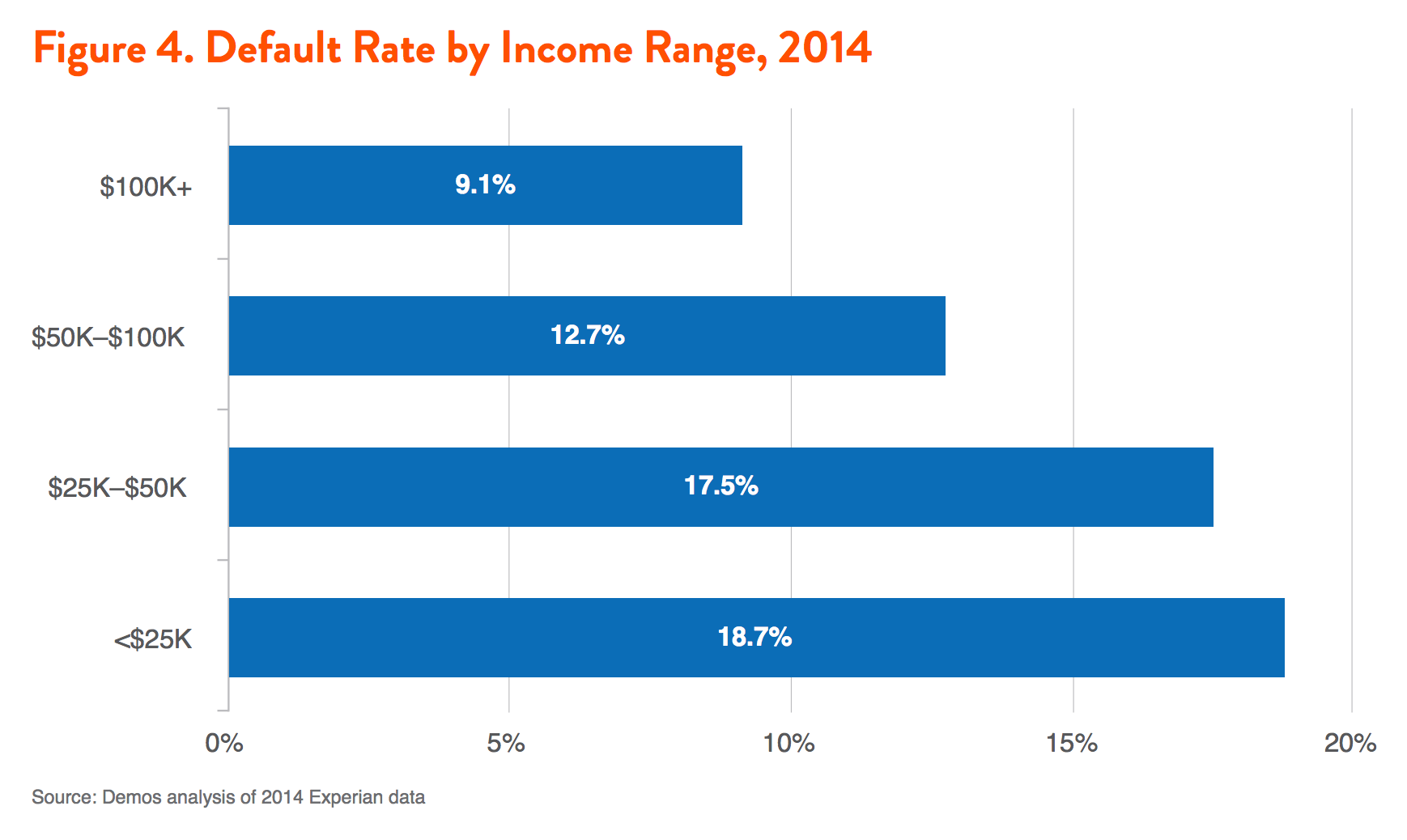

- Lower-income borrowers have higher default rates. Nearly 20 percent of borrowers earning less than $25,000 per year were in default, more than double the 9 percent default rate among borrowers earning more than $100,000 annually.

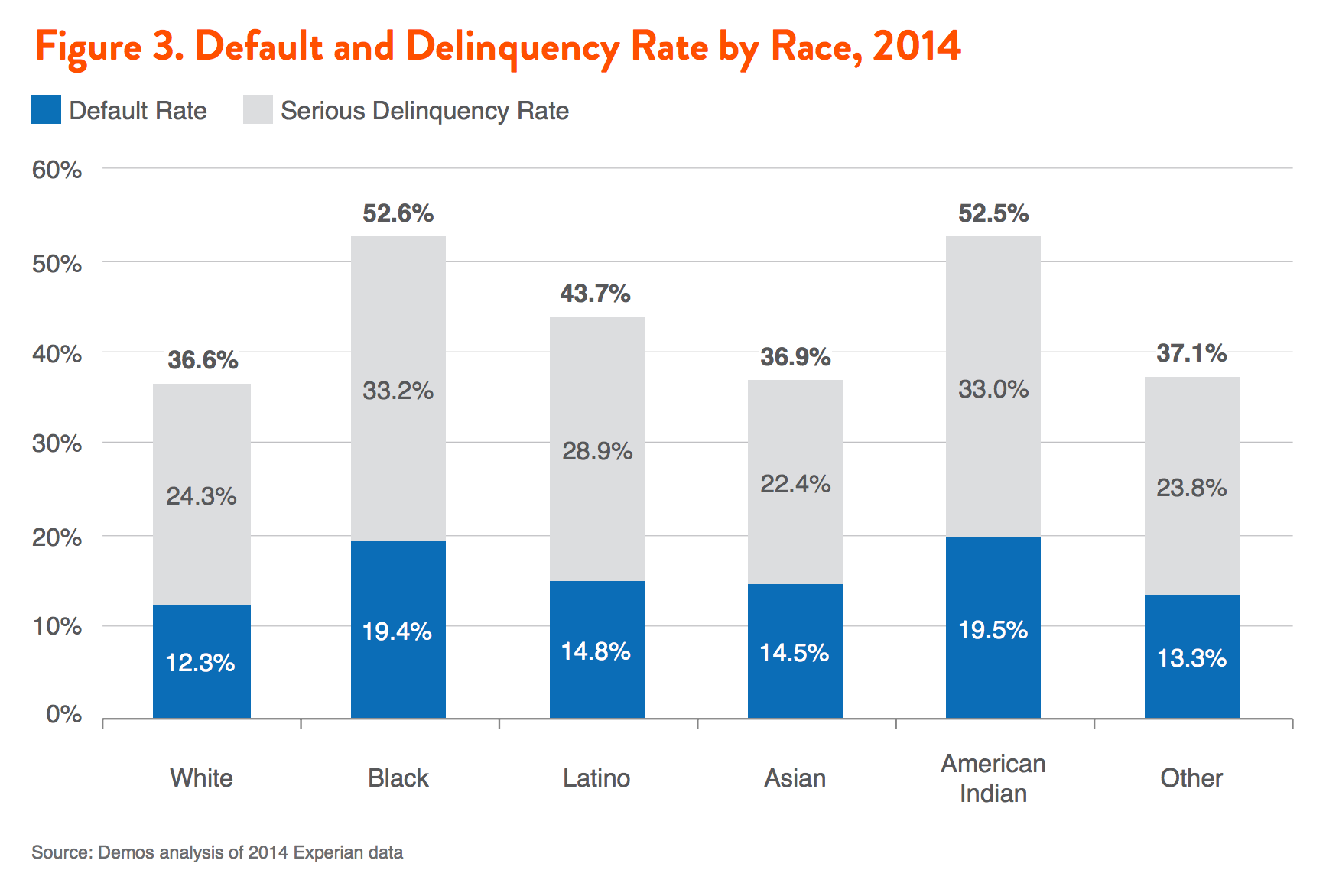

- Borrowers of color face greater difficulty repaying their loans. More than half of black borrowers and 44 percent of Latino borrowers in repayment are either in default or seriously delinquent on their loans.

- A degree is no guarantee against default. Thirty percent of borrowers with bachelor’s degrees and 25 percent of borrowers with graduate degrees are either in default or seriously delinquent on their loans.

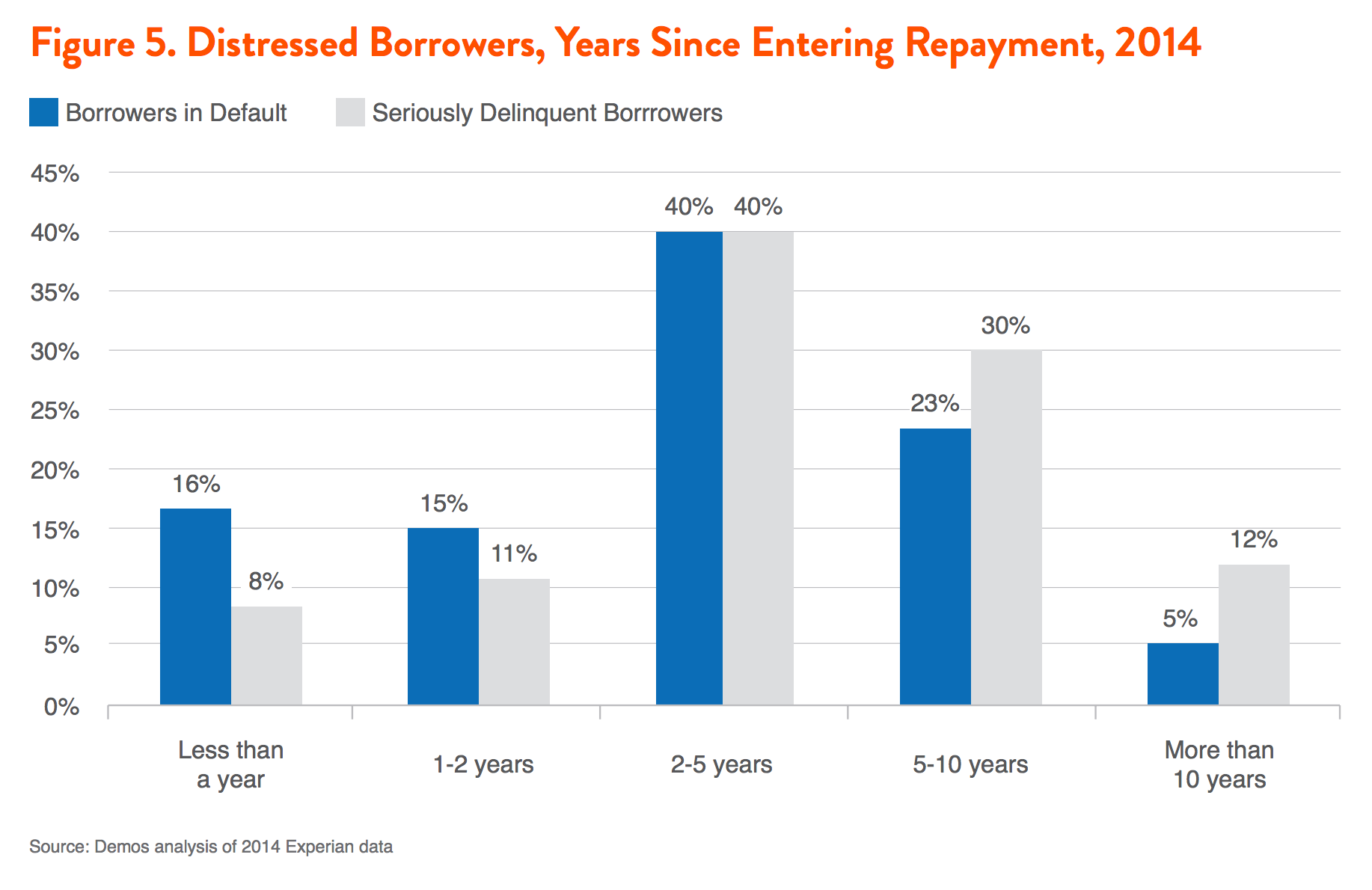

- Borrowers in default or serious delinquency have generally struggled for years to repay their loans. Half of all borrowers in default have been in repayment for more than 3 years; half of all borrowers in serious delinquency have been in repayment for more than 4 years.

- Default/serious delinquency damages borrowers’ financial security. Forty-six percent of borrowers in default and 37 percent of seriously delinquent borrowers have had a credit card in collections or major delinquency status. Just 10 percent of borrowers in default and 15 percent of seriously delinquent borrowers have mortgages.

STUDENT DEBTORS IN REPAYMENT: 3 CATEGORIES

- In order to compare student debtors in similar points in their lives, in this brief we limit our analysis to student debtors in the process of repaying their student loans. Following other analyses of student loan repayment, we divide student debtors in repayment into three groups:

- Borrowers who are current on their payments. Broadly, these are borrowers who are having little difficulty repaying their student loans. This group includes all borrowers in repayment who have either never been late on their student loan payments or have been at most a month late at any point during their repayment process.

- Borrowers who are seriously delinquent on their payments. This group includes borrowers experiencing serious difficulty repaying their loans, and who are at risk of a future default. It includes all borrowers in repayment who have been at least 3 months (90 days) late on their student loan payments, but who have not yet entered default. Since lenders can declare a borrower in default if they are 270 days (9 months) past due on their payments, the majority of these borrowers are thus between 3 and 9 months past due.

- Borrowers in default. This group of borrowers has experienced a default on their student loans. To be in default, a borrower must be 270 days or more past due on their payments, and have had their lender declare them in default (sometimes, a lender may decline to do so for a variety of reasons).

We use the term distressed borrowers throughout the brief to collectively refer to borrowers in either of the latter two categories, i.e. who are either seriously delinquent or in default.

DATA

The calculations for this brief were generated from a data set on the demographics and finances of student debtors obtained from Experian. The data set was created from the credit records of 35,000 student debtors, sampled from Experian’s entire credit database in December 2014. It contained a wide range, including:

- Several student debt variables, including loan balances, origination dates, and repayment status.

- A range of variables on debtors’ other finances, including credit card and mortgage debt, collections, and bankruptcy.

- Demographic variables, including borrowers’ age, gender, location (city, state, zip), income, and education level. These last two were imputed by Experian at our request, using their own proprietary models.

- An individual’s race is legally not allowed to be included in their credit history or report. Demos modeled the race of the individuals in the data set using a predictive model based on each individual’s income, sex, and zip code, among other factors.7

CHARACTERISTICS OF DISTRESSED BORROWERS

Most borrowers in default owe small amounts

Individuals in default on their student loans borrow at essentially the same levels as borrowers able to pay on time. The median student loan balance among borrowers in default is $16,381, slightly higher than the median balance of borrowers who are current on their payments, $15,654. As Figure 1 shows, a third of borrowers in default owed less than $10,000 in 2014, 56 percent owed less than $20,000, and 83 percent owed less than $50,000. It is important to note that these owed amounts include fines, capitalized interest, and other penalties; thus, the original amounts borrowed were likely much lower for many borrowers now in default.

When we examine the default rate by amount of student debt, we find no relationship between the amount borrowed and the chance that a borrower defaults on their loans. As Figure 2 shows, borrowers with the smallest balances—less than $10,000 in student debt—defaulted on their student loans at almost the exact same rate as borrowers with the largest balances—more than $100,000 in debt; their default rates were 13 percent and 14 percent, respectively. Borrowers with balances between these two extremes—with between $20,000 and $100,000 in debt—defaulted at almost the exact same rate as well. This clearly shows that default is not tied to the amount of debt taken out to pay for college, but rather caused by borrowers’ economic and other circumstances.

More likely to be people of color

The race of a student debtor is one of the largest predictors of repayment difficulty. As Figure 3 shows, students of color are significantly more likely to default on their student loans than white students. More than 19 percent of black student debtors and 20 percent of American Indian student debtors are in default, compared to 12 percent of white student debtors. Seriously delinquent borrowers are also more likely to be people of color: almost one-third of black student debtors and 29 percent of Latino student debtors were seriously delinquent on their student loan payments, significantly greater than the 23 percent of white student debtors who were seriously delinquent. Overall, black student debtors are 16 percent more likely to be in default or seriously delinquent than white student debtors; Latino borrowers are 8 percent more likely. The largest

contributors to black and Latino borrowers’ higher default rates are lower average incomes for college graduates of color, and higher attendance at sub-par for-profit schools whose degrees are less valuable or worthless. For black student debtors, who tend to have higher average student debt balances, these factors make their debt more difficult to repay.8 The lower incomes of graduates of color, in particular, make taking on debt especially risky for them. The median white worker with a bachelor’s degree earned $63,338 in 2014, about $13,000 and $11,000 more, respectively, than the median income of their black and Latino counterparts.9 If the loan payments for the average indebted white graduate are around $3,500 per year, this means that the average white graduate with student debt is in better financial shape than the average black or Latino graduate with no student debt.10

More likely to have lower incomes

A borrower’s income is one of the other strong predictors of default. Nearly 20 percent of borrowers earning less than $25,000 per year were in default, more than double the 9 percent default rate among borrowers earning more than $100,000 annually, as shown in Figure 4. In fact, the default rate is significantly lower for borrowers earning $50,000 per year or more, which shows how deeply the possibility of default is tied to whether borrowing for a college degree paid off in higher earnings for borrowers, which can often be beyond borrowers’ control.

The relationship between the economic payoff of borrowing for college and default is also clarified by the higher default rates among borrowers who were unable to complete their degrees: 15 percent of borrowers with some college but no degree were in default in 2014, compared to more than 9 percent of borrowers with bachelor’s degrees and 8 percent of borrowers with graduate degrees. In fact, completion and debt often form a vicious cycle, as the pressures of mounting debt burdens make students more likely to drop out.11 It’s important to emphasize that though borrowers with degrees are less likely to default on their loans, a degree is no guarantee that loan repayment is easy; in total, 30 percent of borrowers in repayment with bachelor’s degrees and 25 percent of borrowers with graduate degrees are either in default or seriously delinquent on their loans.

Have generally struggled for years to repay their loans

Though borrowers can default on their student loans as quickly as 9 months after beginning repayment, most borrowers who end up in default or seriously delinquent on their student loans in fact struggle to repay their loans for years before falling into one of these two statuses, as Figure 5 shows. Half of all borrowers in default have been in repayment for more than 3 years; in other words, among borrowers in default, the median time since entering repayment was 39 months. Seriously delinquent borrowers have been struggling even longer to get ahead on their loans: more than half have been in repayment for more than 4 years. This should be no surprise: as we force a greater share of students to take on increasingly large debts, the greater the chance that an adverse shock—a long spell of unemployment, a large unexpected medical expense, etc.—makes a borrower unable to repay their loan. And if, as seems likely, the average duration of repayment increases as average debt burdens continue to rise, the greater the chance a major adverse shock will hit a borrower sometime during repayment.

EFFECTS OF DEFAULT AND DELINQUENCY ON FINANCIAL SECURITY

Given that most borrowers who struggle with repayment are simply students for whom the economic benefits of a college degree didn’t materialize (or didn’t materialize quickly enough to prevent hardship), the damaging effect of default and delinquency on their financial security is particularly burdensome. Because, unlike other kinds of debt, we don’t allow borrowers to modify or discharge their student debt burdens in bankruptcy, or refinance their loans to lower interest rates, these debt burdens can lead to damaged credit, the inability to purchase a house, and even bankruptcy, despite the lack of relief it provides.

Distressed student debtors are significantly more likely to declare bankruptcy, despite the fact that their student loans still must be repaid after doing so: more than 11 percent of borrowers in default have declared bankruptcy, compared to 8 percent of seriously delinquent borrowers and just 4 percent of borrowers who are current on their student loans. Individuals struggling to repay their student debt also have a hard time repaying their credit cards: 46 percent of borrowers in default and 37 percent of seriously delinquent borrowers have had a credit card in collections or major delinquency (180+ days past due), compared to just 11 percent of student debtors who are current on their payments. These gaps are likely due to distressed borrowers being forced to postpone credit card payments, leading many lenders to send their credit card debt to collections. These difficulties are reflected in distressed borrowers’ credit scores: among borrowers in default the mean credit score is 541, and among seriously delinquent borrowers it is 539, compared to a mean credit score of 678 for on-time borrowers. These average scores mean that most borrowers in default or seriously delinquent borrowers have a credit score rated as “poor” or “very poor,” which would make it nearly impossible to obtain a loan.

This difficulty obtaining credit is shown in both the homeownership rates and credit card usage of distressed student debtors. Just 10 percent of borrowers in default and 15 percent of seriously delinquent borrowers have mortgages, compared to 38 percent of borrowers who are current on their payments. Borrowers in default and seriously delinquent borrowers are also much less likely to have credit card debt, probably because lenders have closed their credit cards or denied applications for new ones. Thirty-three percent of borrowers in default and 46 percent of seriously delinquent borrowers have credit card debt, far lower than the 78 percent of on-time borrowers who do.

WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE?

To address the symptoms of student debt, we need a comprehensive solution, one that both provides relief for existing debtors and prevents the next generation of students from having to go into debt to obtain a college degree. To prevent future students from being forced to borrow, we need to reinvest in public higher education, restoring funding to the levels of decades prior with funds earmarked for reducing tuition and additional need-based grant funding. Demos’ policy recommendation, the Affordable College Compact, proposes a federal-state compact to ensure debt-free public college, in which the federal government provides matching grants to states that ensure the majority of their poor, working- and middle class-students can attend college without incurring debt or financial hardship. Relief for current borrowers needs to include allowing existing borrowers to refinance their student loan debt at a lower interest rate, and reforming bankruptcy laws to allow for the discharge of student debt for the borrowers in deep financial distress. The Compact represents a fair, achievable path to return to debt-free college. But action needs to happen now, before even more borrowers fall behind on their student loans and end up in a financial hole they can’t climb out of.

ENDNOTES

4. Demos calculations of 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances.

7. First, we used the 2013-2014 American Community Surveys to generate demographic breakdowns for each zip code in the country, as well as average incomes for each race/ethnicity in each zip code. Then, we assigned a probability that each person in our Experian data set was of a particular race/ethnicity based on their reported zip code and income in the Experian data set. We then aggregated these probabilities over the entire data set to generate the overall default rates by race.

10. Assuming the average white graduate owes $25,000 (from NPSAS 2012 data), earns $63,338 (as above), and is in the standard repayment plan.