Introduction

In today’s competitive economy, nothing is more important than getting a college education. Yet college tuition costs in the U.S. have been increasing at a breakneck pace, making college unaffordable for millions of Americans. In the last decade alone, the average tuition at public 4-year universities has risen by nearly $3,000. There is a broad consensus that out-of-control tuition is a serious problem for the nation, making it much more difficult for young people, particularly those from low-income families and communities of color, to complete a college degree. However, there is no such agreement on why tuition is increasing. Experts have blamed rising tuition on everything from administrative bloat, to increased availability of grants and loans, to campus construction booms. Demos and others, in contrast, have focused on declining state funding as the culprit, as we demonstrate in our Great Cost Shift series. Although academics and media alike have tried to put the question to rest, public confusion on this issue is one reason why effective solutions remain illusory in almost every state.

This brief attempts to pinpoint the cause(s) of spiraling tuition by taking a deep dive into public university revenue and spending data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ Delta Cost Project Database. In the brief, we split public 4-year universities into two categories: research institutions—schools that have a high level of research activity and award a significant number of doctorates—and master’s and bachelor’s universities—schools that primarily award master’s and/or bachelor’s degrees. Research institutions consistently enrolled about 60 percent of all undergraduates at public 4-year institutions in the decade covered by the brief, while master’s and bachelor’s universities accounted for the remaining 40 percent. We find that declining state appropriations for higher education is indeed the primary driver of rising tuition, responsible for 79 percent of tuition hikes at public research universities between 2001 and 2011and 78 percent of tuition hikes at public master’s and bachelor’s universities over the same decade. Increased spending on administration accounts for another 6 percent and 5 percent, respectively, at the two categories of institutions, and increased grant and loan aid has had a negligible effect, at most. Finally, the purported construction boom’s impact on tuition has been minimal as well, as we estimate spending on construction has accounted for 6 percent of tuition increases at both research and master’s/bachelor’s universities.

Spending at Public Universities: A Snapshot

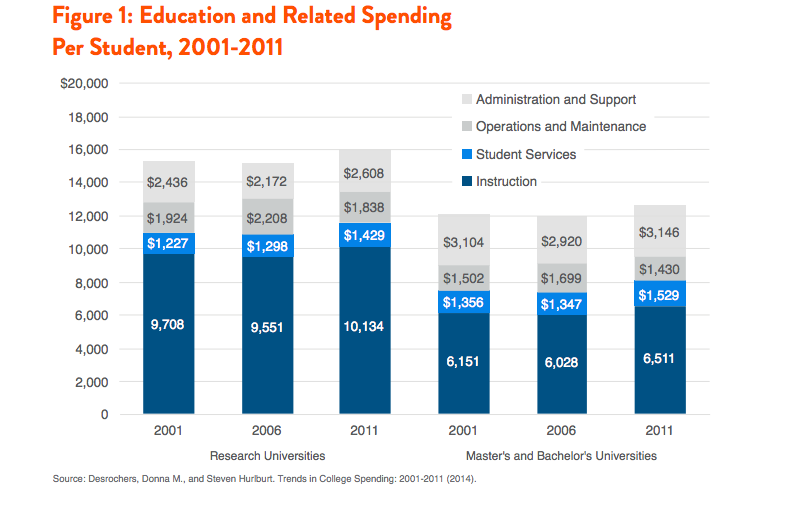

Overall spending per student grew at a modest pace over the past decade: expenditures rose 8 percent and 1 percent, respectively, at research and master’s/bachelor’s universities between 2001 and 2011. Spending on “education and related expenses”—spending on the core educational mission of universities, including spending on instruction, student services, and a share of administrative and operations costs—climbed at an even slower pace, rising just 5 percent at research institutions and 4 percent at master’s/bachelor’s universities, as depicted in Figure 1. We focus on education and related spending in this brief because they are the expenses paid for by tuition revenue and state support. Other spending, including on auxiliary enterprises (including dormitories, dining services, and athletics) and federal grants and contracts, are primarily self-funded by revenue from their own independent activities and services. As the figure shows, increased spending on instruction and student services accounted for the majority of the spending increase; administrative/support expenditures rose just $172 and $42 per student, respectively, at the two institutional categories.

Notably, these spending increases pale in comparison to tuition increases: net tuition revenue—total revenue from tuition and fees, net of institutional aid—at research institutions rose by $3,628 per student and by $2,463 per student at master’s and bachelor’s universities. These large tuition increases, coupled with slow spending growth, suggest that the cause(s) must be on the revenue side of the balance sheet, and that administrative “bloat” and student aid are at most minor contributors to tuition increases. However, before we can definitively label these oft-cited factors as myths, we need to dig a little deeper into each to see whether the spending trends in smaller expense categories match the observed modest increases in spending overall.

Download the full report to read more