Introduction

All of us—people of all races and in communities of every description across America—work hard to sustain our families, pay the bills, and gain some financial security. When employers cut hours and hold down pay, working Americans struggle to find stability. And when the same employer pushes high-fee loans right outside the human resources office, draining bank accounts nearly as fast as a paycheck can fill them, working people never have a chance. That is what employees describe at Marriott International, a $42 billion corporation and the world’s largest hotel company.

The dynamics of unstable pay at Marriott and high-cost lending by its affiliated credit union take the income disparities between Marriott’s predominantly black and Latino workforce and its overwhelmingly white corporate leadership and enable them to metastasize into growing disparities in wealth. A study of these dynamics illustrates how everyday corporate practices feed growing racial inequality in America.

This brief unpacks these dynamics. First, we describe the scope of the nation’s racial wealth inequality and its origins in public policy and corporate practices. We look at how Marriott’s current scheduling practices, with fluctuating hours that lead to unpredictable paychecks that too often fall short, destabilize the lives of the people who work there. Next, we examine how high-fee “Mini Loans” at the financial institution set up for Marriott employees exploit this instability, stripping the wealth of the primarily African-American and Latino workers who clean rooms and common areas, cook and serve food, staff front desks, help guests with luggage, and do the other work that has enabled Marriott to become the multi-billion-dollar corporation it is today. We then consider a different loan product offered by the same employee credit union—an advantageous home mortgage loan that disproportionately serves higher-income, white employees, including company executives, living near Marriott’s corporate headquarters in Bethesda, Maryland. Together, this amounts to a transfer of wealth from working people of color, fueling the racial wealth gap. Corporate leaders could make decisions that would make a large and profitable corporation like Marriott—which claims to value diversity and inclusion—a powerful force for racial equity as easily as they have chosen to reinforce growing inequality.

America’s racial wealth gap: fueled by public policy and corporate practices

Wealth plays a critical role in enabling families to both handle current financial challenges and make investments in their future. Families that have accrued some wealth have a financial buffer to deal with unexpected costs, like an emergency hospital bill or disruptions in household income such as a layoff, without falling into debt or poverty. Over the longer term, wealth can expand the prospects of the next generation, helping to pay for college, provide a down payment for a first home, or capitalize a new business. Yet public policies and corporate practices contribute to a tremendously inequitable distribution of wealth in America: According to data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, the median white household possessed $13 in net wealth for every $1 held by the median black household in 2013. That same year, median white households possessed $10 for each $1 held by the median Latino/a household.

Research probing the causes of the racial wealth gap has traced its origins to current and past public policies and business practices that systematically lock black, Latino, and other families of color out of wealth-building opportunities that benefit white families. A prominent example is the government redlining between 1934 and 1968. Redlining limited both public and private investment in black neighborhoods, and undermined wealth-building prospects for generations of African-American families. The high-fee Mini Loans promoted by the Marriott Employees Federal Credit Union resemble another historical case of employers and lenders profiting from workers’ economic insecurity: the post-Civil War sharecropping system that kept formerly enslaved black families and some poor white farmers in the South trapped in a cycle of debt. The country store was at the center of this exploitative system. Since most sharecroppers did not have a steady cash flow, they used their future crop as collateral to finance loans from store merchants. At the end of the growing season and after they had paid the landowner, sharecroppers used the remainder of their crop to repay their debts to the store merchant. Country stores had little competition and often set interest rates as high as 50 or 60 percent. Focused on paying back the loans, sharecroppers grew volatile cash crops like cotton rather than subsistence crops that could feed their own families. Thus, sharecroppers were forced to borrow more money to purchase food at inflated prices from the country store. White store merchants and landlords built their own wealth on a system that left predominantly African-American sharecroppers in perpetual debt.

As wealth is handed down across generations, the outcomes of past injustice like the sharecropping system carry forward. Ostensibly “color-blind” policies in effect today—such as divestment from public goods like education that have the potential to give all Americans an equitable start in life, and tax policies that further subsidize already wealthy, predominantly white households—reinforce existing wealth disparities. Lending is one area where historic injustices profoundly shape current outcomes: Generations of past discrimination in employment, lending, education and housing have produced racial disparities in credit history. As a result, past discrimination is “baked in” to determinations of creditworthiness: Credit scores and other lending algorithms disproportionately represent African-American loan applicants as riskier borrowers, even when a lender never explicitly considers their race. Other ongoing corporate practices, from unfair pay and scheduling to discriminatory hiring and promotion, also reinforce racial disparities in income and wealth.

Marriott’s unstable schedules create unstable livelihoods

Unstable schedules are common in the hospitality industry, as they are in retail and other industries structured around low-paying, hourly employment. Marriott, like other hotel and restaurant operators, profits from its power to quickly adjust the work hours of the people employed in its hotels and resorts based on immediate customer demand. As employment expert Susan Lambert explains, “Employers tend to keep head counts high for low-level hourly jobs so that they have a large pool of workers who can be scheduled for short shifts at times of peak demand. Technologies like computerized scheduling systems and forecasting tools make it possible to predict and monitor sales and calibrate work schedules not just by the day but by the hour. Employees are called in or sent home as needed.”

Some Marriott hotels are cutting work hours even when demand is strong. At the Philadelphia Marriott Downtown, for example, the total number of hours worked by employees have declined over the past 5 years even as the hotel’s occupancy rate and revenue have increased.

Yet Marriott workers depend on their jobs to earn a living. When managers cut work hours and workers’ paychecks fall short, household budgets come apart. Rent is still due and groceries cost the same, but there is suddenly less income to pay for them. Unstable schedules with short hours can even increase household costs when working parents scramble to find childcare to cover a last-minute change in work hours and workers must pay for transportation to and from a shift that may last only a couple of hours. Research suggests that workers of color bear the brunt of unstable scheduling across the economy: African-American and Latino workers are more likely than their white counterparts to be relegated to part-time jobs despite wanting stable full-time employment, and early-career workers of color are more likely to receive schedules with little notice. At the same time, racial wealth disparities mean that workers of color have fewer other resources to draw on when hours are suddenly cut and paychecks are smaller than expected.

Marriott promotes high-fee loans to struggling workers

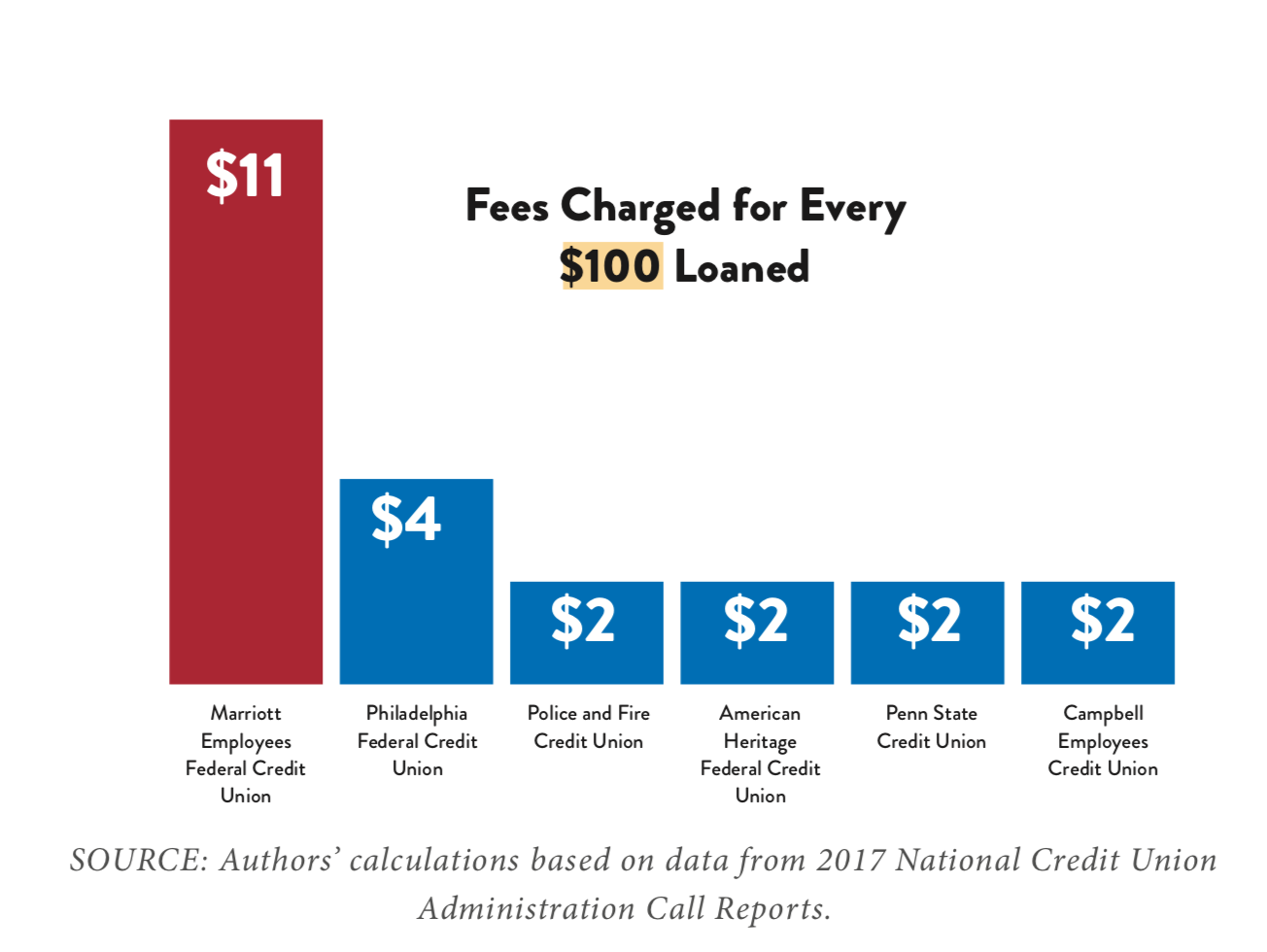

As Marriott creates economic instability in the lives of its workers with irregular scheduling, its affiliated financial institution generates an unusual volume of revenue through high-fee financial products. The Marriott Employee’s Federal Credit Union (MEFCU), a 33,000-member institution, is open to employees and retirees (and their family members) of Marriott International, Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, Sodexo, and other Marriott affiliates, contractors, and franchisees. MEFCU’s entire Board of Directors—with the exception of the credit union CEO—is composed of Marriott International senior management and executives. While the credit union is officially a non-profit designated as serving primarily low-income members, the uncommonly high fees it charges raise questions about whose interests are truly served. In 2017, MEFCU charged members $3,125,001 in fees—more in fees for every dollar loaned than any other credit union of its membership type. As the chart below illustrates, MEFCU charges $11 in fees for every $100 loaned, substantially more than peer institutions.

One particularly troubling loan product is the high-fee $500 “Mini Loan,” which workers at some Marriott hotels can apply for directly from their workplace human resources office, according to employees. The Mini Loan’s interest rate is fixed at 18 percent, and the credit union charges a $35 application fee for each Mini Loan. According to the National Consumer Law Center’s Annual Percentage Rate (APR) calculator, the effective rate for MEFCU’s Mini Loan is 46.616 percent when including the $35 application fee (treating the amount financed as $465 rather than $500).

Workers interviewed at the Philadelphia Marriott Downtown report using Mini Loans to afford rent, food and other monthly expenses when Marriott’s fluctuating hours result in a short paycheck too small for them to make ends meet. The Mini Loan is repaid in 6 monthly payments automatically deducted from the worker’s credit union account, just as their paychecks may be automatically deposited. Some workers report taking out one Mini Loan after another when they are not assigned enough work hours to keep up with expenses (including their payments on the Mini Loan).

Marriott’s predominantly African-American and Latino frontline workforce may be particularly vulnerable to this type of high-cost lending because of the long history of families of color being excluded from the wealth-building opportunities that have benefitted white families. As a result, people of color remain less likely to have savings to fall back on to weather an emergency, buy a car, attend college, pay a medical bill, start a business, or make a down payment on a home. The lack of wealth and greater need for credit to meet these expenses disproportionately expose communities of color, as well as low-wealth white communities, to predatory lending. In a vicious cycle, predatory lending strips additional resources from families and communities, increasing their reliance on borrowing in the future.

Although the Mini Loan terms are not as exploitative as those offered by commercial payday lenders, Marriott workers should be able to expect better from a non-profit institution promoting loans out of their own employer’s human resources office. While Marriott could be offering stable hours that enable working people to stick to a budget and build wealth, its credit union instead suggests employees go into debt to make up for lost income by offering a high-fee loan that drains employee savings.

Marriott offers advantageous home loans primarily to higher-income, white employees

The Marriott Employees Federal Credit Union does offer some employees a lucrative opportunity to build wealth: Like most credit unions, MEFCU offers its members low- interest real estate loans. Traditionally, purchasing a home has been a vital way for American families to accumulate wealth as they pay down mortgages over time. In 2017, MEFCU originated 113 real estate loans amounting to a total of $24,557,255. Yet MEFCU’s home loans have disproportionately gone to Marriott’s higher-paid employees. Between 2011 and 2017, 99.7 percent of the dollars loaned went to applicants with incomes higher than that of the median Marriott worker, including administrative and executive employees. Some of these loans have gone to top executives of Marriott International. Loans disproportionately financed properties in suburban Maryland, near Marriott’s corporate headquarters.

At the same time, Marriott’s real estate lending practices also reveal troubling racial disparities: According to data released in accordance with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, 59 percent of black applicants were denied a home loan from MEFCU between 2011 and 2017—nearly double the denial rate of white applicants. African-American applicants only received a total of 12 home loans from MEFCU during the 6-year period, which amounted to just 6 percent of the total home mortgage dollars loaned by the credit union. Moreover, even among wealthier applicants—those making more than $100,000 annually—black applicants were denied twice as often as their white counterparts.

Conclusion

Across America wages are nearly frozen, work is becoming ever more insecure, and the divide between the top 1 percent of very wealthy households and the vast majority of working people is growing. Researchers find that, at current rates of wealth accumulation, it would take 242 years for black families to catch up to the amount of wealth that the median white household owns today. Marriott International and MEFCU did not create these conditions, but they fuel them through corporate practices including unstable schedules, high-fee financial products aimed at its struggling and predominantly African- American and Latino workforce, and mortgage loans that serve its better-off employees. A large and profitable corporation like Marriott—which claims to value diversity and inclusion—could be a powerful force for racial equity. Instead, corporate leaders have chosen policies that reinforce growing inequality.