Latinos make up a fifth of Chicago residents and 15 percent of the medium-sized donor pool, but only 6 percent of the large-donor pool. African-Americans make up 39 percent of the Chicago population, but 8 percent of mid-level donors and a mere 4 percent of large donors. Asians make up 3% of the population, 4% of mid-level donors and 3% of large donors. And finally, whites make up 39 percent of the population they make up an overwhelming share of both the large and mid-level donor pool. Women make up 34% of medium-sized donors, but 27% of large donors (see Figure 6).

DONORS HAVE DIFFERENT POLICY PREFERENCES THAN MOST CHICAGOANS

According to data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Studies, [10] only one-third of non-donors who live in Chicago support the Bowles-Simpson plan to cut expenditures on Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and defense spending to reduce the debt—while nearly two-thirds of Chicago donors support the austerity plan.

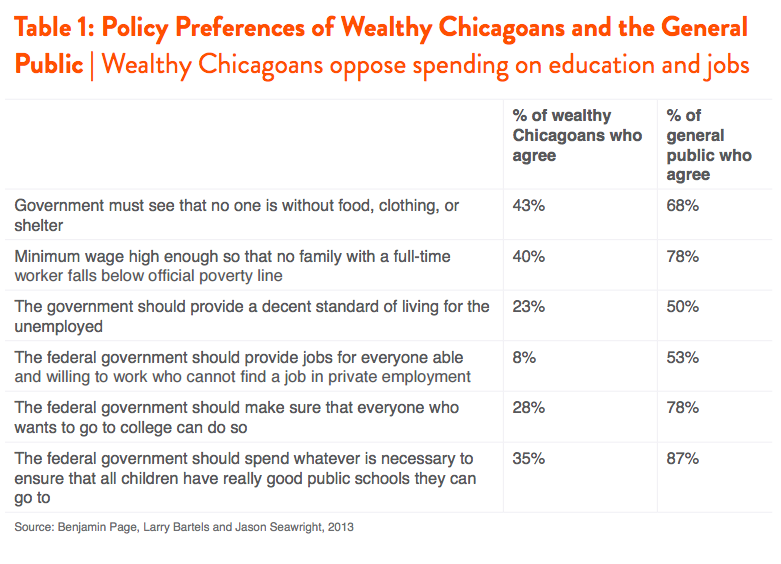

In 2012, three political scientists performed a survey of wealthy Chicagoans (called the Survey of Economically Successful Americans, or SESA) and compared their preferences to those of the general population. Those surveyed had a median wealth of $7.5 million and two-thirds of them were political donors. [11] The authors use the sample to examine the policy preferences of the wealthy in general, but given that the survey was Chicago-based it offers insights into how the donor class influences policy. As the table shows, the wealthy are far less likely to support a living wage and the government ensuring a decent standard of living.

While more than three-quarters of the general public agree that the government should “make sure everyone who wants to go to college can do so,” only 28% of the wealthy agree. While nearly nine in 10 average Americans agree that the government should spend whatever necessary to ensure all children attend a good public school, only 35% of the rich agree.

Although the questions are not identical to the SESA survey, a poll of Illinois residents finds that only 16 percent favor cuts to K-12 education, and less than a quarter support cuts to programs for poor people.[12] Only 13 percent of Illinois residents support cuts to programs for those with mental health problems.[13] There are deep divides between the donor class and the general public. The current path Chicago is following, with cuts to mental health services, infrastructure and public schools, is responsive to the preferences of the donor class, not average Chicagoans. Chicago has closed 49 schools, predominantly in black neighborhoods. [14] In addition, the city has closed six of the city’s 12 mental health clinics, which was supposed to pull in $2.2 million in savings, though the city then paid $500,000 to private facilities in order to meet demand.[15] A recent wave of spending cuts hit Chicago State University, the only state college that predominantly serves Black students, particularly hard. The college may have to close, or dramatically reduce staff and classes offered.[16]

Cuts to higher education can be harmful, as studies show that higher education spending bolsters voter participation, improves economic growth and lowers crime rates.[17] In addition, public education cuts saddle students with debt, which leads to a lifetime wealth loss[18] and disproportionately harms students of color.[19] Such cuts are unpopular with the residents of Illinois, who according to a 2015 poll, overwhelmingly oppose cuts to state universities (36 percent in favor) and programs for the poor (23 percent in favor). [20] The cuts show how the influence of the wealthy white male donor class can disproportionately impact people of color and low-income people.

THE CASE FOR PUBLIC FINANCING

A study of New York City’s 2009 municipal election finds that “donors giving $10 or less live in neighborhoods that are more racially diverse than the city as a whole.”[21] Research suggests that the city’s public matching system (which uses public funds to match small donations) increased the diversity of the city’s donor pool.[22] Other research suggests that the small donor pool tends to be more racially diverse than the large donor pool.[23] The data from Chicago show this was well (see Figure 6).

After public financing was passed in Connecticut, Demos talked with numerous legislators about their experiences. On legislator reported, “I announced my reelection bid in February and by April, I was done fundraising. So, from April to November, I could focus only on talking to constituents. Without public financing, I would have been fundraising through that entire period.”[24] This fits well with research by political scientist Michael G. Miller who examines competitive elections and finds that traditionally funded incumbents and challengers reported spending 11% of their time on fundraising, while fully funded incumbents spent less than 1% of their time fundraising and challengers spend about 1.5% of their time fundraising.[25] Miller finds a nearly 12 percentage point increase in the share of time clean election candidates spend interacting with voters.[26] Other political science research supports this conclusion.[27] Another elected official reported that, “Before public financing, during the session…there were ‘shakedowns’ where lobbyists and corporate sponsors had events and you as a legislator had to go. That’s no longer a part of the reality.”[28]

CONCLUSION

Chicago’s democracy is being distorted by an overwhelmingly, white, wealthy and male donor class. But public financing provides a clear solution. The “Fair Election Ordinance,” introduced on January 13, 2016 would match all small donor contributions up to $175, increasing the influence of the most diverse small and mid-level donor pool. It would reduce the influence of big money donors, creating a more equitable democracy. A study of the New York Public Financing system show that it dramatically increased donor diversity, and the data from Chicago suggest why: the small donor pool is more diverse. [29] By empowering small donors, Chicago would reinvigorate its democracy.

APPENDIX

The donor demographic data in this report are based on analysis of Illinois State Board of Elections data performed by Brian Schaffner and Jesse Rhodes of University of Massachusetts Amherst in collaboration with Demos. They used the Illinois State Board of Election’s website in order to find data on contributions made during Chicago’s 2015 elections for Mayor and Alderman. To find donations to each of two mayoral candidates, Rahm Emanuel and Jesus Garcia, they searched for donations made to each candidate’s campaign starting from the end of the prior election cycle in 2011 (more specifically, starting May 16th, 2011, the day Rahm Emanuel was sworn in) through the end of the runoff election on April 7, 2015. This provided a unique spreadsheet containing the donation amount and the names and street addresses of the contributor for each candidate. They used the same time parameters in our search for donations made to the Alderman race. There were 50 city council seats up for election in 2015; they therefore restricted our search to contributions made during the election cycle to candidates seeking the office of Alderman. These search criteria returned a spreadsheet containing the amount and source of a donation, and the name of the candidate to whom a donor made a contribution.

They then collapsed the data collected from the Illinois Election’s website to create one record for each individual donor in each of the groupings. That is, if one individual gave $200 to Emanuel three times, they created a single record for that individual reflecting that she had given $600 total to Emanuel. These records were then matched into Catalist to extract demographic information on the donors. They were able to successfully match 92% of Emanuel’s donors, 95% of Garcia’s donors, and 89% of donors to Aldermen races into Catalist. Thus, this data provides very comprehensive coverage of Chicago donors. For gender, income and race, around 2% to 5% of the population could not be coded. These respondents were removed from sample. This does not significantly affect the final analysis.

[1] Abe Scarr, “Final Numbers Show Big Money Dominated Chicago Mayoral Elections,” July 16, 2015, Illinois PIRG Education Fund, available at: http://illinoispirgedfund.org/news/ilf/final-numbers-show-big-money-dominated-chicago-mayoral-elections. Additional calculations based on an analysis of data provided by Scarr to Demos. The data were retrieved from the Illinois State Board of Elections. The data span the period from 2/23/2011 to 4/07/2015. According to reporting by the Chicago Tribune, between April and June, Emanuel raised an additional $2.1 million and Garcia raised an additional $1.4 million. Bill Ruthhart, “Final tally: Emanuel raised $24.4 million to win re-election,” Chicago Tribune, July 17, 2015, available at: http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-rahm-emanuel-campaign-fundraising-met-0718-20150717-story.html. The percentage of donors coming from outside of Chicago is based on the Demos dataset, not the PIRG’s report.

[3] Sean McElwee, “A New Study Shows How Donors Distort Democracy,” Policyshop, February 18, 2015, available at: http://www.demos.org/blog/2/18/15/new-study-shows-how-donors-distort-democracy.

[4] These numbers that analyze the comparative donor pools of Emanuel and Garcia are based on Demos and PIRG analysis of Illinois State Board of Elections Data. The data span the period from 2/23/2011 to 4/07/2015, during which time Emanuel raised $22.3 million and Garcia raised $5.1 million. The full totals come from reporting by the Chicago Tribune, which reports that between April and June, Emanuel raised an additional $2.1 million and Garcia raised an additional $1.4 million. That leaves the full total at $24.4 million for Emanuel and $7.1 million for Garcia. Bill Ruthhart, “Final tally: Emanuel raised $24.4 million to win re-election,” Chicago Tribune, July 17, 2015, available at: http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-rahm-emanuel-campaign-fundraising-met-0718-20150717-story.html.

[7] See Appendix 1 for a full methodology of the data.

[8] These numbers refer only to donors over $150, which is the disclosure limit.

[9] Adam Lioz, “Stacked Deck: How the racial bias in our big money political system undermines our democracy and our economy,” Demos, (2015), available at: http://www.demos.org/publication/stacked-deck-how-racial-bias-our-big-money-political-system-undermines-our-democracy-a-0.

[10] These data use four surveys pooled from 2010 to 2014, and include all political donations, not simply those running for municipal office.

[11] Benjamin Page, Larry Bartels and Jason Seawright, “Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans,” Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 11, No. 1 (March 2013), available at: http://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~jnd260/cab/CAB2012%20-%20Page1.pdf

[16] CBS Chicago, “Chicago State University Students Rally In Loop To Protest Possible Shutdown,” February 8, 2016. Available at: http://chicago.cbslocal.com/2016/02/08/chicago-state-university-students-plan-loop-march-to-protest-possible-shutdown/.

[18] Robert Hiltonsmith, “At What Cost?,” Demos, August 2013. Available at: http://www.demos.org/what-cost-how-student-debt-reduces-lifetime-wealth.

[19] Mark Huelsman, “The Debt Divide,” Demos, May 19, 2015. Available at: http://www.demos.org/publication/debt-divide-racial-and-class-bias-behind-new-normal-student-borrowing.

[25] Michael G. Miller, Subsidizing Democracy, (Cornell University Press, NY: 2013).