American democracy is based upon the fundamental principle of one person, one vote—the simple notion that we are all equal before the law and should have an equal say over the government decisions that affect our lives. But unfortunately our system often more closely resembles one dollar, one vote as wealthy donors enjoy vastly disproportionate influence over who runs for office, who wins elections, and what issues make it onto the agenda in Washington, DC. This threatens the integrity and legitimacy of our democracy, as ordinary citizens come to the justified conclusion that the system is rigged and their voices are being drowned out in a sea of campaign cash.

We must reduce the undue influence of wealthy donors by amplifying the voices of all Americans. The Government By the People Act increases the power of the small contributions that ordinary citizens can afford to give, providing incentives for congressional candidates to reach out to average constituents, not just dial for dollars from wealthy donors. It’s the single best policy we can immediately enact to democratize the influence of money in politics. Though the Supreme Court, in a long line of cases from Buckley v. Valeo to Citizens United v. FEC, has tied the People’s hands, blocking us from enforcing common-sense limits on the use of big money in politics, we remain free to tackle the problem from the other side of the equation—providing incentives to bring more small donors into the system.

The Government By the People Act has four key provisions:

- Creates the Freedom from Influence Fund to match contributions of up to $150 to participating candidates 6-to-1 or more;

- Provides a $25 refundable tax credit for small contributions;

- Provides enhanced matching funds in the final 60 days of a general election for candidates in high-cost races (because of an onslaught of outside spending, for example); and

- Creates People PACs, or small donor committees, that aggregate the voices and power of ordinary citizens rather than wealthy donors (as traditional PACs tend to do).

We need a government of, by, and for the people, not bought and paid for by wealthy donors. This proposal puts the U.S. Congress back in the hands of ordinary Americans.

THE PROBLEM: The Wealthy Dominate Politics, Leading to Skewed Outcomes

Time and again, our government fails to produce the policy outcomes that the majority of Americans support— from strong investments in jobs, roads, and rails to a robust minimum wage and a fair tax burden for the one percent. Recent political science research points to a key reason why, empirically documenting the disproportionate influence of wealthy donors in our political process.

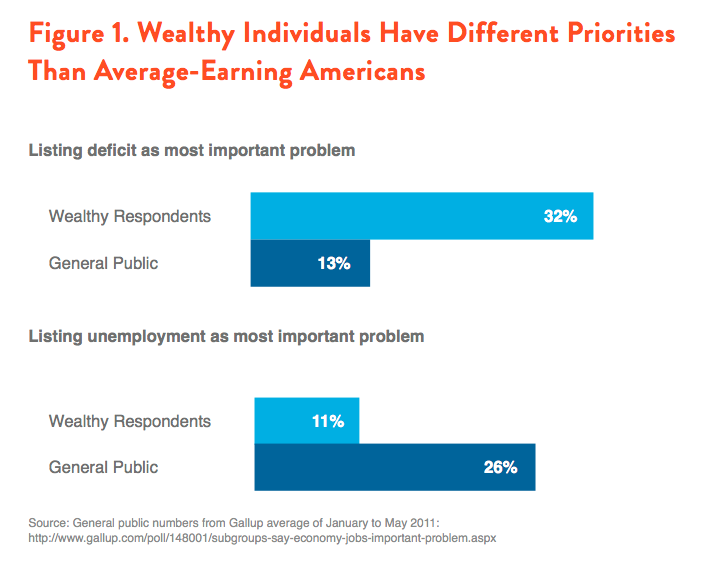

The wealthy have sharply different policy preferences and priorities than does the general public—especially on basic issues of how to structure the economy. While differences in opinion are the lifeblood of democracy, the policy preferences of the wealthy are much more likely to translate into actual policy outcomes in the U.S. When the preferences of the top 10 percent of the income ladder diverge from the rest of the public, the 10 percent trumps the 90 percent nearly every time. This lead the author of the leading study on the topic to conclude that “under most circumstances the preferences of the vast majority of Americans appear to have essentially no impact on which policies the government does or doesn’t adopt.”

The central reason for this dramatic gap in whose policy preferences receive attention is our big money campaign finance system. Since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United ruling, there has been a lot of discussion about the dramatic rise in outside spending driven by unlimited contributions by wealthy donors. In 2012, nearly 90 percent of Super PAC funding from individuals came in contributions of at least $50,000 and almost 60 percent came in $1,000,000 or more.

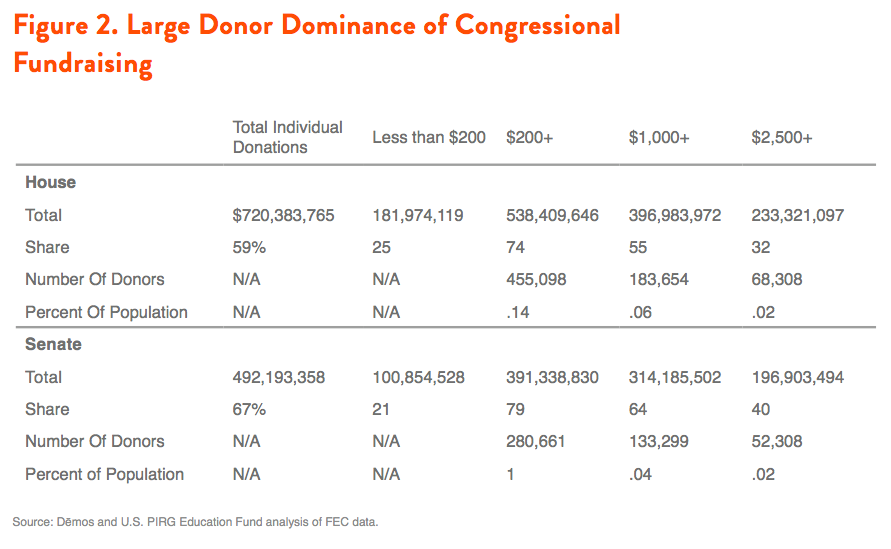

But, many don’t realize that candidate fundraising is also dramatically skewed towards the wealthy. For example, 2012 candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives got the majority of the funds they raised from individuals (55 percent) in contributions of at least $1,000—from just 0.06 percent of the U.S. population. The equivalent figure for Senate candidates was 64 percent of funds from just 0.04 percent.

In some ways, the dominance of candidate fundraising by a small minority of wealthy donors is more significant than even the billions of dollars of outside spending. Candidate fundraising dynamics affect who runs for office, the views of those who do, and ultimately who wins elections.

Because candidates need to raise a threshold amount of money to run viable campaigns, those who can afford to give $1,000 or $2,000 to campaigns—the donor class—act as de facto gatekeepers, filtering the pool of “acceptable” candidates long before voters have their say at the polls.

The need to secure large donations from a very small percentage of the population in turn influences how candidates spend their time, and with whom. Miles Rapoport, current Demos president and former Connecticut state legislator and Secretary of State describes his experience running for Congress in 1998:

Every night I would lock myself in a room with a bag of chips and some strong coffee and make my calls, homing in on people who could ideally give me at least $500 or $1000 or more. And, when I was talking with these potential donors I found that their problems and concerns weren’t the same as the majority of folks I was looking to represent in Congress. I heard a lot about how excessive regulations were strangling their business or health care costs for their workers were a real burden. I was running as a progressive candidate and so my first instinct was to say, “now wait a minute, that’s not exactly right.” But, my goal on the phone was to get the contribution. So, by the end of the night, I found myself saying things like “well, that’s an interesting point you make and when I’m in Washington you should come by and we can talk more about that.” I wasn’t changing my positions, exactly, but there was definitely a shift in emphasis, and I could feel myself shifting as I spent more and more time talking to a very narrow set of wealthy donors. My sense of what was pressing and important may have been affected, and my sense of what types of positions I needed to be open to in order to win my race and get into Congress was certainly affected.

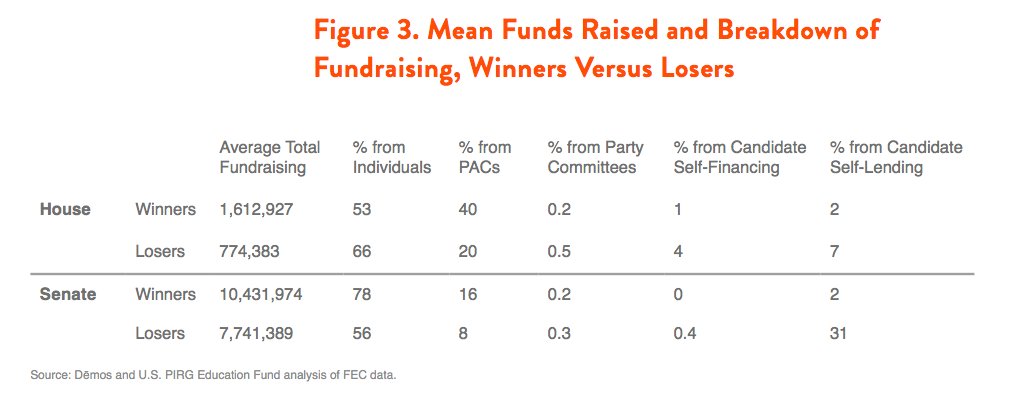

In the end, of course, money plays a substantial role in determining who wins elections. In the 2012 elections 84 percent of House candidates who outspent their general election opponents won their elections, and winners raised on average more than twice as much as losers. While correlation should not be confused with causation and there are complicating factors, it seems fairly apparent that money matters. At the very least all of the major players in the elections game—candidates, donors, campaign consultants, etc.—act as if it matters; and this fact alone leads fundraising to drive decision-making.

The bottom line is that big money in politics warps Congress’ priorities and erodes public trust. Americans’ confidence in government is at an all-time low. Significant majorities express the concern that the actions of their government are responsive to the wishes of financial supporters; that their government does not represent their interests or respond to the needs of the broad populace anymore; and that this reflects a corruption of government and its ability to serve the public. For example, in May 2012, a prominent public polling firm reported that “[v]oters believe that Washington is so corrupted by big banks, big donors, and corporate lobbyists that it no longer works for the middle class.”

In our distorted democracy, economic might is translated directly into political power and to a large extent the strength of a citizen’s voice depends upon the size of her wallet. This runs directly counter to core American values and threatens the very legitimacy of our democracy.

A KEY SOLUTION: The Government By the People Act

In February 2014, Congressman John Sarbanes, along with scores of colleagues in the U.S. House of Representatives, introduced H.R. 20, the Government By the People Act. The goals of the legislation are to shift the balance of power away from wealthy interests and towards ordinary voters, and change the way candidates approach running for federal office so that they spend more time reaching out to regular voters and less time raising money from a small number of rich donors, thus deterring corruption and its appearance.

The Government By the People Act employs three basic strategies to accomplish its policy objectives in the current electoral environment: amplifying the voices of ordinary citizens by matching small contributions with public funds; empowering more Americans to participate in campaigns by providing a tax credit for small political contributions; and helping grassroots candidates fight back against special interest outside spending by providing an additional late-campaign match. These key elements combine with other features to create a voluntary system that most candidates for U.S. House should ultimately choose to use, because it frees them from the burdens and obligations of large-dollar fundraising and provides a more attractive way to run for office that is responsive to current campaign conditions.

Questions & Answers About the Government By the People Act

Q: HOW WILL THIS SYSTEM ACTUALLY WORK?

It’s a voluntary system that will help grassroots candidates run on people power. Instead of raising most of their campaign cash from big donors in DC or New York, candidates will raise a large number of small contributions from people back home. Candidates qualify for the system by demonstrating local grassroots support—at least 1,000 in-state contributions adding up to at least $50,000. Then they agree to focus their campaigns on small donors and forgo contributions of more than $1,000. All of their contributions of $1 to $150 are matched on a six-to-one basis by a public fund (or an even higher match ratio under certain conditions). Contributors get a refundable tax credit of $25. Each candidate’s public funding is capped at a certain amount, and there would be strict enforcement of campaign finance laws, including disclosure of all donations.

Q: HOW DOES THIS BILL HELP AVERAGE VOTERS INCREASE THEIR CLOUT COMPARED WITH WEALTHY DONORS?

Right now wealthy donors command more attention from candidates because big checks help win elections. That’s like having a bigger megaphone, or a direct line to power, which undermines people’s faith in our system. The Government By the People Act turns that dynamic on its head. First, the My Voice tax credit helps more people get into the game by making a small contribution. Next, the Freedom From Influence Fund will match small contributions 6-to-1 or more. That means that a $150 contribution becomes worth at least $1,050—which is actually more than the $1,000 that participating candidates are allowed to take from a wealthy donor. So, for participating candidates small contributions from average constituents can actually be worth more than big checks from wealthy donors. And, even the $20 or $35 that a single mother or blue-collar worker can spare becomes significant.

Q: HOW DOES THIS PROPOSAL CHANGE THE WAY THAT CANDIDATES RUN FOR OFFICE?

Right now most candidates treat fundraising and campaigning as two separate activities. They chase campaign cash from the donor class—dialing for dollars to Wall Street or seeking out lobbyists on K Street—and they search for votes at events back in their districts. And, because the costs of campaigns keeps rising they often spend much more time with donors who can give $1,000 or more than with voters who may only be able to chip in $50. Many (or even most) candidates actually hate dialing for dollars—but they play the game to win according to the current rules. Matching small contributions 6-to-1 or 9-to-1 can change this equation, freeing candidates to spend their time and energy courting constituents and seeking $50 or $100 contributions—which will now translate into significant resources for their campaigns. Candidates will spend more time hearing from average voters at barbeques, fish fries, constituent coffees, and door-knocking in their districts, and less chasing big money from the one percent.

Q: WILL THIS REALLY CHANGE HOW WASHINGTON, DC WORKS? WILL IT HELP ADVANCE THE PRIORITIES OF ORDINARY VOTERS?

No one law will completely transform Washington overnight. But, this proposal can change the way that Members of Congress run for office and who they listen to. Government in the U.S. responds almost exclusively to the preferences of the donor class because he who pays the piper calls the tune. For example, the very rich are much more concerned with deficits than job creation, and that focus has dominated conversations in Washington for the last several years. When Members of Congress can fund their campaigns with small contributions from their constituents they won’t face competing incentives when legislating. They can prioritize their constituents’ needs without worrying about how the next bill they sponsor will go over with lobbyists on K Street.

Q: HAVE PROGRAMS LIKE THIS BEEN SUCCESSFUL IN THE PAST?

Yes. Different types of systems that use public funding to boost the power of small donors are in effect in Arizona, Connecticut, Maine, New York City, and many other places. Since Connecticut’s system took effect in 2008 more people are running for office and contributing to campaigns, lobbyists’ influence has declined, and policies the public wants like paid sick days and a stronger minimum wage have passed. New York City’s system is probably the most similar and has seen candidates rely much more heavily on small donors, the merging of fundraising with campaigning, and a more diverse donor pool.

Q: HOW WILL THIS PROPOSAL AFFECT THE DIVERSITY OF THE CANDIDATE OR DONOR POOL?

One of the problems with our current big money system is that large donors are much more likely to be white and male than the population as a whole. Cities and states that have tried programs intended to boost the power of small donors have generally seen increased diversity in both the donor and candidate pools, and we can expect the same at the federal level. For example in New York, 24 times more small donors from one poor, predominantly black neighborhood gave to City Council candidates (with a matching program) than to State Assembly candidates (without one). In Connecticut, both Latinos and women increased their representation in the legislature following the enactment of a public funding program. And, the program should increase economic diversity in the Congress as well. More than half of Congress are now millionaires, and just 2 percent have had working class backgrounds over the past century. This has a lot to do with the fact that in the current system it’s hard to get elected without a network of rich friends.

Q: HOW DO WE KNOW THIS PROPOSAL WON’T WASTE PUBLIC MONEY ON CANDIDATES WHO EITHER AREN’T VIABLE OR DON’T FACE CREDIBLE OPPOSITION?

There are several provisions in the Government By the People Act that target and conserve public funds. First, candidates must demonstrate a threshold level of local public support to be eligible to receive any public funds. They must raise at least $50,000 from at least 1,000 people in their home states—not easy to do for fringe candidates. Next, all public funds are tied directly to private contributions. Unlike in past proposals, there are no lump sum grants. To access more public funds, candidates must convince more Americans to invest in their campaigns. Third, candidates can only carry over a limited amount of public funds into the next election cycle. And they have to spend one dollar of private funds for each dollar of public funds. So, there’s no incentive for those without viable opponents to keep drawing from the Freedom From Influence Fund and they can’t spend all the public money while hording private contributions. Finally, those who choose to access additional public funds available in the final 60 days of the campaign must give up their ability to carry over any public funds into future elections—so candidates will only choose to access this money if they really need it because they face a legitimate competitor.

Q: WITH ALL THE SUPER PAC MONEY COMING IN, WILL THIS BILL REALLY MAKE A DIFFERENCE? WILL CANDIDATES EVEN USE IT?

This bill is designed with current campaign conditions in mind—including the constant threat of a barrage of outside spending. First, it’s important to remember that Super PACs play a significant role in a relatively small portion of House races, and usually in the general election. One of the core purposes of this proposal is to make it feasible for lots of ordinary Americans without extensive networks of wealthy friends and associates to run for office. This usually means running in a primary election, most often before Super PACs are engaged in the race. But, it works for expensive general elections too. Through it’s enhanced match program, the proposal provides the chance for candidates in highly competitive races to raise up to $500,000 in additional matching funds in the final 60 days of a general election. This provision is designed, in part, to give grassroots candidates a fighting chance against last-minute attacks by Super PACs or other outside spending groups. The caps on public funds are also designed to keep pace with the ever-increasing cost of campaigns. The caps are tied to the most expensive races in the previous cycle, so candidates who choose to participate in the program can rely on sufficient funds to remain competitive. These features should make the program attractive to many candidates for U.S. House, even those expecting tight races with significant outside spending.

Q: WHAT ABOUT RICH CANDIDATES WHO FUND THEIR OWN CAMPAIGNS?

Unfortunately, because of misguided Supreme Court rulings, we can’t prevent millionaires from attempting to buy public office by bankrolling their own campaigns. But, this bill doesn’t subsidize them. In order to qualify for public funds, candidates have to agree to strict limits on self-funding.

Q: CAN THIS BILL REALLY SURVIVE IN THE SUPREME COURT, WHICH SEEMS QUITE HOSTILE TO CAMPAIGN FINANCE LAWS?

It’s true that the Roberts Court is very hostile to even common-sense restrictions on the use of big money in politics. But this proposal focuses on raising the voices of average voters rather than imposing limits—so it’s clearly constitutional even under the Court’s unreasonable rulings. There are no mandatory contribution or spending limits and no matching funds “triggered” by outside or opposition spending. It clearly provides a way to reduce corruption and fight Americans’ belief that our politics are bought and sold, goals strongly supported by the current jurisprudence. In short, there’s nothing for the Court to object to in this bill.

Q: HOW DOES SOMEONE TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THE TAX CREDIT?

It’s easy—a donor simply makes a small contribution to one or more candidates of her choice (no more than $300 per year to any one candidate) and saves a record of that contribution (either a paper receipt or an online confirmation). Then, at tax time, the donor will see a line item for the credit on her 1040A or 1040EZ form and lists the amount of her credit-eligible contributions (up to a $50 for an individual or $100 for a joint filer, translating to a $25 or $50 credit).

Q: WHAT HAPPENS IF A DONOR GIVES A $100 CONTRIBUTION FOR THE GENERAL ELECTION THAT IS MATCHED 6-TO-1 AND THEN GIVES A SECOND $100 CHECK TO THE SAME CANDIDATE FOR THAT SAME ELECTION?

Only total contributions of up to $150 per election from the same donor are eligible for a public match. Since the second check would bring the contributor’s total to $200, the candidate must do one of two things: either return $50 to the donor, or return the public match she received on the first $100 to the Freedom From Influence Fund. Obviously in this case it will make much for sense for the candidate to return $50 to the donor and get a 6-to-1 or 9-to-1 match on $150 for a total of $1,050 or $1,500.

Q: WILL THIS PROGRAM BE DIFFICULT TO ADMINISTER?

No, the bill sets up a special commission within the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to ensure that the program runs effectively and efficiently. Aside from this commission, most of the burden will fall on candidates who use the system, but they will find that the benefits—a significant public match on the funds they raise, and being able to focus their time listening to constituents—will far outweigh the administrative costs. The most complicated part will be keeping track of multiple contributions from the same donor to the same candidate so we know if a donor goes over the $150/election threshold and therefore none of her contributions are eligible for a public match. But, candidates already use software that assigns unique identifiers to individual donors and are already responsible for reporting the names, addresses, and employers of contributors who give several small contributions that add up to $200 or more over the course of an election cycle—so this is nothing new.

Q: WHY SHOULD WE SPEND TAX DOLLARS ON POLITICAL CAMPAIGNS?

There’s some truth to the old sayings that you get what you pay for and he who pays the piper calls the tune. Someone is paying for candidates to run for office, and it can either be ordinary citizens, helped along with a limited amount of public funds, or it can be wealthy donors. Right now, most Americans believe—accurately—that government more responsive to donors than voters, and it’s undermining their faith in our democratic process. The extremely small cost of putting ordinary citizens at the center of political campaigns (a rounding error on our $3 trillion annual budget) can pay huge dividends in terms of government responsiveness to ordinary citizens and in turn voters’ confidence in the legitimacy of our democracy.

Q: HOW MUCH WILL THIS BILL COST TAXPAYERS, AND HOW WILL WE PAY FOR IT?

The CBO has not yet formally scored the bill, but even the high-end estimates would mean we’ll save many times the cost by eliminating boondoggles that are inevitable when politicians are accountable to large donors. For example, following the enactment of a similar program in Connecticut, the state was able to save $24 million by returning unclaimed bottle deposits to the public rather than beverage companies. Savings at the federal level would be substantially larger. And, we can offset the cost of the proposal by cutting tax subsidies for special interests.

Key Provisions of the Government By the People Act

1) Amplifying Our Voices: The Freedom From Influence Fund

Twenty-five dollar or even $100 contributions can feel insignificant to both donors and office-seekers when candidates for Congress are raising the majority of their funds in $1,000 and $2,500 checks. Why would a candidate knock on doors for days on end collecting small checks when she can attend one fundraiser at a law office or lobby firm and pull in $25,000 or $30,000 in two hours?

The Government By the People Act creates the Freedom from Influence Fund to change this dynamic. The point of the Fund is to amplify the voices of ordinary citizens and make a modest contribution worth a significant amount to a candidate, changing how (and with whom) candidates spend their time while running for office.

Here’s how it works:

The Public Match

Only Small Contributions Matched

The Fund provides a public match on small contributions to participating candidates—up to $150 per election (or $300 per election cycle). Larger contributions are not matched at all. In other words, the Fund does not match the first $150 of a $500 contribution. The match is targeted to truly small donors to amplify their voices and bring new people into the system. It does not subsidize the existing donor class.

The match ratio depends upon how much a candidate wants to target her campaign to small donors (more on this below). The basic program provides a 6-to-1 match—so a $150 contribution is worth $1,050 to a participating candidate. Candidates who choose to further target their campaigns to small donors by accepting additional restrictions on their fundraising are eligible for a 50 percent bonus on this match. That same $150 contribution would then be worth $1,500.

Cap on Public Funds

There is a cap on the total amount of public matching funds a participating candidate may receive, and a cap on the amount of public funds a candidate may hold over for future elections.

For the baseline 6-to-1 match, public funds are capped at half of the cost of the 20 most expensive winning House campaigns from the previous cycle, which is currently about $3.25 million. For the 50 percent bonus enhanced match program, public funds are capped at the full cost of the 20 most expensive races, or approximately $6.5 million. And, in especially competitive races—campaigns that often feature lots of outside spending—participating candidates are eligible for an additional $500,000 in public funds in the final 60 days (further explanation in the “Enhanced Match Funds” section below).

Limits on Carrying Over Public Money for Future Elections

Candidates receiving the baseline 6-to-1 match are permitted to carry over $100,000 in public funds into the next election cycle. Candidates receiving the 50 percent enhanced match are permitted to carry over $200,000 into the next election cycle. Any carried-over public funds must be returned to the Freedom From Influence Fund if a candidate does not run for office again.

Participating candidates are permitted to carry over as many private funds as they wish; but they are required to spend $1 of private funds for every $1 of public funds (while they have private funds) so that they cannot horde private funds for carry-over purposes. These carry over limits reduce the incentive and ability for candidates in noncompetitive races to raise and then horde public funds.

These caps, along with the additional match described below, are designed to keep the program to a stable, predictable cost while still providing enough public funds to enable candidates to run viable, competitive campaigns within this system—which is essential for motivating candidates to choose to participate.

Fundraising Restrictions

The Freedom From Influence Fund is targeted to candidates who will change the way they campaign; it is not designed to function as an additional source of money for candidates who are still seeking to fund their campaigns from lobbyists and the donor class. To facilitate this targeting, participating candidates must agree to certain fundraising restrictions.

To qualify for the baseline 6-to-1 match, candidates must:

- Accept no contributions from individual donors of more than $1,000 per election.

- Accept no political action committee (PAC) contributions except from People PACs. These are special small donor PACs that raise money in contributions of $150 or less (more on this below).

- Agree to strict limits on self-funding.

To qualify for the 50 percent bonus on the 6-to-1 match, candidates must:

- Accept no contributions from individual donors of more than $150 per election. In other words all of their fund- raising must be from matchable contributions.

- Accept no PAC money at all.

- Agree to strict limits on self-funding.

Qualifying for the Program: Demonstrating Sufficient Local Grassroots Support

To safeguard public resources, only candidates who can demonstrate sufficient local grassroots support to run a viable campaign are eligible for matching funds. In order to qualify (for either the regular or “enhanced” match), candidates must secure at least 1,000 contributions from residents of their home state for a total of at least $50,000.

2) Empowering More Americans to Participate: The My Voice Tax Credit

Most Americans believe there is too much money in politics. But, more troubling than the overall amount is the source of these funds. The core problem, as described above, is that too great a percentage of political money comes from a relative handful of wealthy donors, leaving elected officials accountable to the donor class rather than a broad swath of American voters. In addition to limiting the size of contributions (which can be difficult to do effectively under current Supreme Court precedent), a key way to attack this problem is to motivate millions more middle and lower income people to make financial contributions, balancing out the influence of the rich. In addition to the matching funds described above, the Government By the People Act employs two strategies to bring more Americans into the process as small donors.

The My Voice Tax Credit

The Government By the People Act provides a $25 refundable 50 percent tax credit ($50 for joint filers) for taxpayers who contribute up to $300 in a single tax year to any U.S. House candidate. This means that someone who contributes $50 to a candidate can get $25 back at tax time and someone who contributes $100 and files jointly with a spouse can get $50 back—regardless of whether they have affirmative tax burden. The credit would be claimable on both the 1040A and 1040EZ tax forms.

This provision is intended to motivate millions of Americans to contribute to political campaigns who otherwise would not. It will function primarily as a tool for grassroots candidates who can reach out to ordinary voters and say “make a small contribution to my campaign and you can get half your money back.” It can also be used by constituency-based organizations to motivate their members to contribute to candidates they have endorsed.

The fact that the credit is fully refundable is critical, and makes this tool for enhanced participation available to Americans across up and down the income ladder—not just the 57 percent of Americans who earn enough to incur a federal income tax burden.

The tax credit is not a new idea, but rather a policy that has enjoyed support from presidents Kennedy, Truman and Eisenhower and benefited from years of experimentation on the federal and state levels.Experience shows that a properly designed credit can be an effective way to increase financial participation by non-wealthy citizens.

A federal tax credit similar to the one proposed existed from 1972-1986. At peak participation, more than 7 percent of eligible filers took advantage of the credit, compared with the estimated 2-3 percent of Americans who currently contribute to federal political campaigns. Unfortunately, the credit was not refundable and so did not reach the 43 percent of the population that does not incur federal income tax liability.

Analysis of state-level programs shows that contribution incentive programs are most effective when combined with other reforms. The tax credit in this bill should be particularly attractive when combined with the matching program described above, because a small donor can contribute $50, have that $50 matched six-to-one (or nine-to-one) and then receive $25 back—effectively turning a $25 cost into a $350 or $500 contribution.

The My Voice Voucher Pilot Program

In addition to the tax credit, the Government By the People Act includes a three-state federally funded pilot program to provide vouchers that eligible residents can use to make small contributions to federal candidates. Vouchers, like tax credits, are not a new idea—a voucher program was proposed at the federal level as early as 1967, and the idea has been championed by several scholars since.

While a tax credit requires a contributor to give money out-of-pocket and receive a full or partial refund at tax time, a voucher provides up-front resources to be allocated to preferred candidates. This can be critical for citizens who are living paycheck-to-paycheck and may not feel they can afford to make a political contribution, even if they will get some of the money back at a later date. Research suggests that vouchers may go a long way towards reducing income or wealth as a factor in campaign giving.

The voucher pilot program will provide an invaluable opportunity to test vouchers’ potential for engaging non-wealthy citizens and removing wealth as a primary factor in determining who contributes to political campaigns. If the program proves successful, it should be expanded nationwide.

3) Enhanced Match Funds to Fight Back Against Special Interests

The prospect of a last-minute barrage of spending by outside groups like Super PACs, trade associations, and 501(c) (4) nonprofits that can raise unlimited funds (often without disclosing their donors) has changed the face of modern campaigns. Many candidates are feeling pressure to build up larger and larger war chests to fend of this type of potential attack. Once thousands of ordinary citizens have invested in the campaign of a grassroots candidate, and these investments have been enhanced by public funds, we don’t want to see our voices drowned out by just a few millionaires and billionaires and our preferred candidates blown out of the water without any chance to fight back.

The Supreme Court has stymied our ability to prevent these spending onslaughts, but we can provide participating candidates with a fighting chance by helping them raise last-minute resources to fight back.

The Government By the People Act provides optional enhanced match support for participating candidates. Candidates who raise at least $50,000 in small contributions during the match period are eligible for up to $500,000 in public matching funds in the last 60 days of a general election campaign, regardless of whether they have already reached their cap on public funds. Small contributions (up to $150) are matched at a bonus rate of 50 percent above the candidate’s previous match rate. So, a candidate who was previously receiving a 6-to-1 match would receive a 9-to-1 match during this period; a candidate previously receiving a 9-to-1 match would receive a 13.5-to-1 match.

In order to conserve public funds and target this program to candidates who truly need the money because they are in competitive races (as opposed to those who would spend the money to build name recognition), candidates who make use of this enhanced match lose the ability to carry over any public funds into a future election cycle. In the final months of a campaign, each participating candidate will face a choice. If the campaign is a break-the-bank race featuring a barrage of outside spending, she will likely take advantage of the further match and sacrifice her ability to carry funds over into the next cycle. If it is not a particularly high-spending race (and most races across the country won’t be), she will likely forgo the additional public funds in favor of starting her next election with some funds in the bank.

4) People PACs to Aggregate the Power of Average Voters

Political Action Committees (PACs) have a bad name. Most people associate them with special interests influence peddling. But, there’s nothing inherently wrong with a PAC— it is simply a tool for people to aggregate their political power to contribute to or advocate for candidates of their choice. The problem with traditional federal PACs is that they can accept contributions of up to $5,000 per year—nearly 10 percent of median household income, and well beyond what all but the wealthiest Americans can afford to give. Super PACs are even worse—providing a convenient vehicle for millionaires, billionaires, and for-profit corporations to use to dominate elections. So, in practice, PACs serve to aggregate the power of wealthy people and interests, not average citizens.

People PACs capture all of the benefits of a PAC as an organizing tool without the downside of exacerbating the advantages of wealth. People PACs can raise contributions of up to $150 per year from individuals. They can give the same $5,000 to candidates, or make unlimited independent expenditures (as Supreme Court precedent requires).

A $5,000 contribution from a PAC to a candidate is neither corrupting nor unfair when those funds originated in dozens of small contributions that average Americans can afford to give.

Anyone can set up a People PAC to organize his or her fellow citizens. Nonprofit corporations, unions, businesses or individuals would all be permitted to use this tool. Even political parties can start People PACs, and as an incentive for them to do so the Government By the People Act permits parties to make unlimited expenditures that are coordinated with candidates using People PAC funds.

Like tax credits and vouchers, People PACs are not a new idea. Colorado, for example, currently has “small donor committees” that can accept contributions of up to $50 from natural persons (as opposed to $500 for other committees) and make contributions to candidates ten times larger than other political committees ($5,000 to statewide candidates and $2,000 to state legislative candidates as opposed to $500 and $200 respectively).