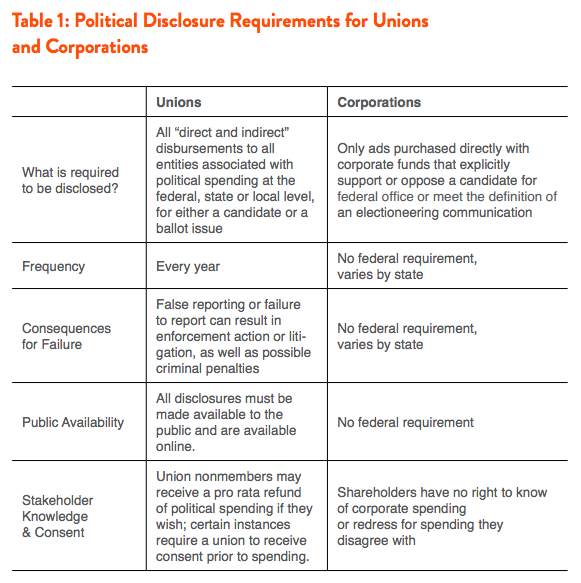

Corporations and unions face very different rules and requirements for their political spending. Labor unions must publicly disclose their political spending and, in some instances, face restrictions about seeking consent from their stakeholders before using political funds. Corporations do not face the same requirements. After Citizens United, there are many avenues through which corporations can spend money in politics without disclosing their financial support for particular candidates or causes. And corporations are not required to seek approval from their stakeholders—in fact, shareholders don’t even have the right under federal law to know if and how a company is spending money in politics.

This paper highlights the differences and broad implications of rules governing political spending by corporations and unions. It recommends Congress adopt a comprehensive disclosure regime like the DISCLOSE Act and the SEC meet its responsibility to update disclosure laws for corporate political spending in the wake of Citizens United.

How did Citizens United v. FEC change the landscape for corporate and union political spending?

In Citizens United v. FEC the Supreme Court struck down the law prohibiting corporations and unions from spending money from their general funds to influence federal elections through independent expenditures or electioneering communications. Previously, they could use money given voluntarily from their members and employees to their political action committees for political spending. The resources available to corporations from their general funds for such political spending are vastly greater than those available to unions. The total revenue for all labor unions in 2013 (a tax category that includes agricultural and horticultural organizations) was $20.8 billion, while total corporate profits in just the 4th Quarter of 2013 was $1.9 trillion.

Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion assumes this new political spending would be transparent and accountable, writing “disclosure permits citizens and shareholders to react to the speech of corporate entities in a proper way.” The opinion argues disclosure would be, “more effective” today because modern technology could make disclosure “rapid and informative.”

Secret political spending has increased exponentially since Citizens United, exactly the opposite of what the Court’s majority posits when they rely on the presumption of transparency and accountability to reach their decision. Citizens United was decided in 2010, and by 2011 a study by the Center for Responsive Politics already found that “the percentage of spending coming from groups that do not disclose their donors has risen from 1 percent to 47 percent since the 2006 midterm elections.”

Because, though the game has changed, the rules have not kept up. The rules that govern disclosure of political spending by unions were in place before Citizens United, but federal disclosure rules have not been updated to cover the new corporate political spending allowed by Citizens United. Federal rules require unions to publicly disclose all political spending and itemize payments over $5,000 with the date, name and address of the recipient, and purpose of the payment. Critically, this includes spending done through third party groups.

Corporations are under no similar blanket federal obligation to disclose their use of corporate resources for political purposes. They do not have to disclose political funds they route the money through other groups such as 501(c)(4) “social welfare” groups and 501(c)(6) business associations – and these tax exempt non-profit groups also are not required to disclose the source of their funds.

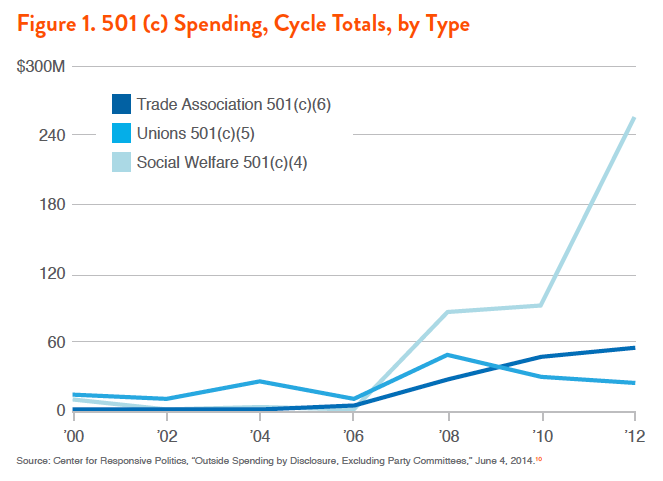

Before Citizens United these dark money groups were not permitted to spend directly on federal elections, but now political spending by political nonprofits and business associations dwarfs spending by 501(c)(5) unions, which do have to disclose:

Without knowing the identities of the sources of the funds, it’s impossible to know how much of the $300 million dollars in dark money spent in the 2012 elections from organized business associations and newly politically active “social welfare” groups came from corporations, let alone which corporations. For example, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce spent $69,506,784 on elections in 2010 and 2012, without identifying the source of those funds, and was the biggest outside spender in the 2010 elections.

Indications are that secret political money will only continue to rise until the rules are changed. At this point in July in the 2012 election cycle, dark money was already at an all-time high compared to the same point at any prior cycle—at about $11 million it was a three-fold increase over the 2008 presidential election. Already so far in the 2014 election cycle more than $34.6 million has been spent by organizations that do not identify the sources of their funds. This is three times the amount of dark money spent at this point in the 2012 presidential election and a shocking fifteen times more than was spent in dark money at this point in the last midterm elections in 2010.

Moreover, most outside spending comes in a flurry in the last month of the election. In 2012, $184 million of dark money was spent on or after October 1st, which represents over sixty percent of the secret political spending tracked in that year. If these trends hold dark money totals this year will certainly break the 2010 midterm record and may even surpass the 2012 presidential election. As it currently stands, we will have no way of knowing the real identities of the political players funding these groups or how much money is coming from corporate sources.

Are unions and corporations subject to the same transparency requirements for their political spending?

No. Both unions and corporations have to report to the Federal Election Commission any political expenditures made to finance independent expenditures and electioneering communications. However, this covers only some of the direct political spending. Otherwise, the regulations governing corporate and union political spending are very different, and allow much more secrecy for corporations than for unions.

The rules requiring disclosure of union political spending are comprehensive and apply to every union with total annual receipts of $250,000 or more. Federal law requires that unions disclose to the Department of Labor “direct and indirect disbursements to all entities and individuals . . . associated with political disbursements or contributions in money.” These LM-2 reports are available on the Department of Labor’s website.

Unions are required to report the money they spend not just in federal candidate elections, but also for state and local office, including judicial races. They are explicitly required to be transparent about spending to support or oppose ballot referenda or to influence legislation. In addition, they are required to report get-out-the-vote campaigns, voter education campaigns, fundraising and any politically-related litigation expenses. Crucially, their donations to 501(c)(4) groups, unlike the similar donations by corporations, must be disclosed on the Schedule 17 form.

In stark contrast, the only agency to which corporations are required to report their indirect political spending is the Internal Revenue Service, and those reports are not made public. If corporations directly engage in political spending, they must disclose their independent expenditures and electioneering communications to the Federal Election Commission. But they can funnel as much dark money as they would like through 501(c) groups. Corporations may voluntarily disclose these contributions, but face no requirement to do so. Of the 100 companies that have chosen to make voluntary disclosures—a micro-fraction of all corporations—many disclose donation amounts, but not the destination of the money, disclose selectively and/or disclose in an untimely fashion.

State disclosure laws are a patchwork and too often ineffective. But after Citizens United several states passed laws to strengthen their disclosure requirements for corporate political spending in state elections. For example, Maryland passed a law requiring companies that spend money to influence state elections to report the spending to their shareholders.

Are unions and corporations subject to the same accountability requirements for political spending?

No. For unions, nonmember workers that benefit from a union contract are able to request a refund of the portion of their fees that went to political activities, and in some instances the Supreme Court has required public sector unions to receive prior consent before assessing fees for political spending.

Corporations are not required to get consent from their shareholders before the corporation uses corporate funds to support or oppose political candidates. Shareholders have no ability to approve or dissent from a corporation’s political spending, or receive a pro rata refund for spending with which they disagree. In the United Kingdom, shareholders vote on a political budget for the company; legislation has been introduced in the United States that would require shareholder approval for corporate political spending.

In the U.S., shareholders don’t even have the right to know how a corporation is spending money in politics. Shareholders have no way to know whether the corporations they are invested in are engaging in political spending, and what they may be supporting without their knowledge. While problematic for a number of reasons, this is most notable for failing to provide the accountability the Supreme Court assumed would be present when it struck down the ban on corporate political spending in Citizens United. Justice Kennedy explicitly wrote that with the advent of the internet, prompt disclosure “can provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable.” But this accountability to shareholders doesn’t exist. In fact, many companies don’t yet have policies requiring that their boards of directors approve political spending by the corporation they control.

This disparate treatment makes even less sense after considering that labor unions represent millions of workers collectively pooling their money to represent their interests and strengthen their voices, whereas business corporations are economic entities created to make profits and avoid liabilities.

What are the implications of the different rules for political spending by corporations and unions?

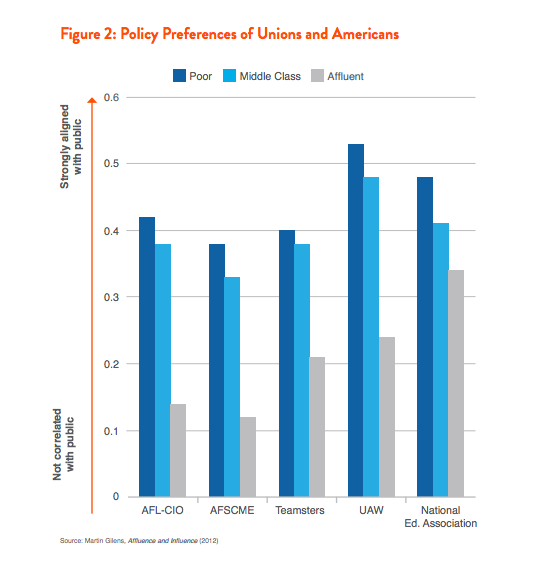

In his book, Affluence and Influence, political scientist Martin Gilens looked at how closely the publicly declared preferences of various interest groups align with the policy preferences expressed by Americans. He found that policy preferences expressed by unions are aligned with the interests of Americans across the income spectrum.

Unions advocate for the positions more closely aligned with the preferences of working people, average-earning middle class Americans, and the relatively affluent (those in the 90th percentile for income). Gilens writes, “based on unions’ strong tendency to share the preferences of the less well-off and the large number of policy areas they are engaged in . . ., unions would appear to be among the most promising interest group bases for strengthening the policy influence of America’s poor and middle class.”

His work also shows that organized business interests are among those least aligned with popular opinion.

Political spending by unions even aligns more closely with the interests of shareholders than that of the profiled businesses and trade associations. After all, most of the shares of public companies are ultimately held by the general public through intermediaries, such as institutional investors charged with managing retirement accounts.

But our campaign finance and other laws and regulations, shaped by Supreme Court decisions, require that unions comply with many more transparency and accountability measures than corporations when they engage in political spending. Corporations are able to wield power through political spending without complying with the same disclosure or consent provisions that apply to unions. This is another way in which our current system stacks the deck in favor of the elite.

What can be done to address the different requirements governing political spending by corporations and unions?

On the heels of Citizens United, Congress came within one vote of overcoming a party-line filibuster to pass the DISCLOSE Act. The need for improved transparency has only grown more clear, and Congress should adopt comprehensive legislation to require disclosure of the true source of funds used for political spending. Voters have a right to know who is influencing their votes and currying favor with their representatives.

The Securities and Exchange Commission has a responsibility to respond to these specific changed conditions by issuing a rule requiring publicly traded corporations to disclose their political spending to their shareholders. This is part of the SEC’s core mission to protect shareholders and the integrity of the markets. Under Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the SEC may require proxy disclosures as “necessary or appropriate in the public interest or for the protection of investors.” There are important investor interests implicated in political spending, e.g., management agency issues, alignments between values, and risk to brand and shareholder value. Shareholders have a right to know how a public corporation is spending money, and they need to know in order to make informed investment decisions.

Many companies are facing shareholder demands for increased transparency around corporate political spending. It was the most frequently filed shareholder resolution in 2014 and 2013. Over 100 companies have entered into agreements with their shareholders to disclose certain elements of their political spending. And yet voluntary disclosure agreements can be difficult to enforce. For example, Aetna gave $7 million to two 501(c)(4) groups in 2012 but didn’t disclose their contributions even though they had a disclosure agreement with their shareholders.

Leading investors are demanding a systemic solution. John Bogle, founder and former CEO of Vanguard has called for greater regulation of corporate political spending, saying “it’s time to stand up to the Supreme Court’s misguided decision; to bring democracy to corporate governance; to recognize the interlocking interests of our corporate and financial systems; and take that first step along the road to reducing the dominant role that big money plays in our political system.”

Conclusion

Unions and corporations face very different regulations when it comes to their political activity. Unions are heavily regulated and are required to report any political spending to several federal agencies, including the IRS and the Department of Labor. Corporations are required to disclose only a part of their political spending and face no accountability even from their own stakeholders. While organized business is free to advocate for the policies they prefer, it is only fair that they do so with at least the same transparency and accountability rules that govern organized labor.