Executive Summary

Today, it is common for employers to look at job applicants’ personal credit history before making a hiring decision. A wide range of positions, from high-level financial posts to jobs doing maintenance work, offering telephone tech support, working as a delivery driver or selling frozen yogurt, may require a credit check. Yet despite their prevalence, little is known about what credit checks actually reveal to employers, what the consequences are for job applicants, or employment credit checks’ overall impact on our society. This report uses new data from Demos’ 2012 National Survey on Credit Card Debt in Low- and Middle- Income Households to address these questions. Overall, we find substantial evidence that employment credit checks constitute an illegitimate barrier to employment.

Key Findings

Among low- and middle-income households carrying credit card debt:

- Employment credit checks are common. Among survey respondents who are unemployed, 1 in 4 says that a potential employer has requested to check their credit report as part of a job application.

- People are denied jobs because of credit checks. 1 in 10 survey respondents who are unemployed have been informed that they would not be hired for a job because of the information in their credit report. Among job applicants with blemished credit histories, 1 in 7 has been advised that they were not being hired because of their credit.

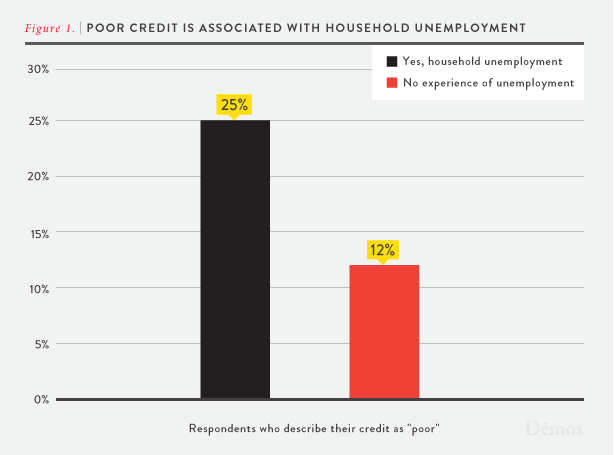

- Poor credit is associated with household unemployment, lack of health coverage, and medical debt. These factors reflect the poor economy and personal misfortune and have little relationship with how well a job applicant would perform at work.

- People of color are disproportionately likely to report poor credit. Our findings are consistent with previous research concluding that African American and Latino households have worse credit, on average, than white households. As a result, employment credit checks may disproportionately screen people of color out of jobs, leading to discriminatory hiring.

- Credit reporting errors are commonly cited as a contributor to poor credit. About 1 in 8 survey respondents who say they have poor credit cite “errors on my credit report” as a reason for their poor credit history. The finding is consistent with other research on the prevalence of errors in credit reports.

We conclude that employment credit checks illegitimately obstruct access to employment, often for the very job applicants who need work the most.

Introduction

Today, it is common for employers to look at job applicants’ personal credit history before making hiring decisions. According to a survey of human resources professionals, nearly half of employers check an employee’s credit history when hiring for some or all positions.

The practice is hardly limited to high-level management positions: even a brief look at a popular job listing website reveals that employers require credit checks for jobs as diverse as doing maintenance work, offering telephone tech support, assisting in an office, working as a delivery driver, selling insurance, laboring as a home care aide, supervising a stockroom and serving frozen yogurt. Some employers also conduct credit checks on existing employees, often when they are considering a promotion.

Yet despite their prevalence, little is known about what credit checks actually reveal to employers, what the consequences are for job applicants, or employment credit checks’ overall impact on our society. This paper, drawing on new data from Demos’ 2012 National Survey on Credit Card Debt in Low- and Middle- Income Households, a nationally-representative survey of 997 low and middle-income American households who carry credit card debt, addresses these questions and finds substantial evidence that employment credit checks constitute an illegitimate barrier to employment.

Credit reports were not designed as an employment screening tool. Instead, they were developed as a means for lenders to evaluate whether a would-be borrower would be a good credit risk: by looking at someone’s history of paying their debts, lenders decide whether to make a loan and on what terms. Accordingly, credit reports include not only an individual’s name, address, previous addresses, and social security number, but also information on mortgage debt; data on student loans; amounts of car payments; details on credit card accounts including balances, credit limits, and monthly payments; bankruptcy records; bills, including medical debts, that are in collection; and tax liens. Credit reports may be purchased by employers through any number of companies that offer employment background checks (which also may include checks of criminal records or other public data) but the credit portion of the report is typically supplied by one of three large global corporations: Equifax, Experian, and Transunion, which are also known as consumer reporting agencies (CRAs). Credit scores —another product used by lenders which consists of a single number calculated on the basis of information in a credit report—are not typically provided to employers.

Employment credit checks are legal under federal law. The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) permits employers to request credit reports on job applicants and existing employees. Under the statute, employers must first obtain written permission from the individual whose credit report they seek to review. Employers are also required to notify individuals before they take “adverse action” (in this case, failing to hire, promote or retain an employee) based in whole or in part on any information in the credit report. The employer is required to offer a copy of the credit report and a written summary of the consumer’s rights along with this notification. After providing job applicants with a short period of time (typically three to five business days) to identify and begin disputing any errors in their credit report, employers may then take action based on the report and must once again notify the job applicant.

These consumer protections are important, yet they are far from sufficient to prevent credit checks from becoming a barrier to employment. Employers can reject any job applicant who refuses a credit check. And while a growing number of state laws restrict the circumstances under which an employer can discriminate against job applicants on the basis of credit history (see endnotes for a list of state statutes), federal law permits employers to use credit history as a basis for denying employment.

Employment credit checks are common — and people are denied jobs because of them

No official source collects and disseminates information on the number of job applicants subjected to credit checks as a condition of employment. The most commonly cited statistic on the frequency of employment credit checks comes from the Society for Human Resources Management (SHRM), which finds 47 percent of employers conduct credit checks on some or all job applicants. But this statistic, based on a survey of fewer than 400 employers, fails to explain how many employees are actually subjected to credit checks, or the likelihood that a job seeker will be required to consent to one in order to be considered for a job. Our survey of low- and middle-income households carrying credit card debt finds that approximately 1 in 7 of these households recall being asked by an employer or prospective employer to authorize a credit check. About the same proportion say they don’t know whether they’ve ever been asked for an employment credit check.

Among those survey respondents who are unemployed, the memories are fresher: 1 in 4 recall that a potential employer has requested to check their credit report as part of a job application.

Yet there is reason to believe that the actual prevalence of employment credit checks may be higher still: in the flurry of paperwork that often surrounds the job application process, applicants may quickly forget the specifics of the many documents they signed. In addition, the prevalence of credit checks is likely to be greater among the higher-income households excluded from our survey, since SHRM finds that employers are more likely to conduct credit checks for senior executive positions and jobs with significant financial responsibility, positions likely to be so well paid as to push household income outside the bounds of our survey in many cases.

To represent a truly widespread barrier to employment, credit checks must not only be widely conducted, but actually become a basis for losing job opportunities. We find that 1 in 10 participants in our survey who are unemployed have been informed that they would not be hired for a job because of the information in their credit report. Among job applicants with blemished credit histories, 1 in 7 has been advised that they were not being hired because of their credit.

However, the true number may be higher still: while the FCRA requires employers to provide official notification when a credit report played a role in the decision not to hire someone, compliance with this provision is difficult to oversee. In the unlikely event that they are investigated, employers who don’t want to bother with FCRA-mandated disclosures can falsely claim that the credit report was not a factor in their decision not hire an employee. Again, the fact that our survey included only low- and middle-income households may also understate the proportion of total job applicants rejected by employers because of their poor credit.

Poor credit is linked to unemployment, lack of health coverage, and medical debt.

Among the low- and middle-income households with credit card debt in our sample, we find that poor or declining credit is associated with households experiencing job loss, lacking health coverage, or having medical debt. We also find that households containing children are more likely to report poor or declining credit.

It’s easy to understand how having an income-earner in one’s household out of work for an extended period of time might make it more difficult to keep up with bills and thus to maintain good credit. We find that households coping with prolonged unemployment were more likely than others in our sample to have other household members work extra hours or get an additional job, borrow money from family and friends, dip into retirement savings, or sell valuable items such as a car or jewelry to deal with unexpected expenses. But these measures were not always enough: 31 percent of households who have had a member out of work for two months or longer in the past three years say their credit score has declined over the same period of time, compared to just 22 percent of those who haven’t experienced extended unemployment in their household. Similarly people from households with someone out of work in the past three years are more likely to describe their credit as “poor” and less likely to describe it as “good” or “excellent” than those that haven’t experienced extended unemployment in their household.

Moreover, people with low credit scores are significantly more likely to have incurred expenses related to job loss over the past three years. Nearly half (45 percent) of those with credit scores below 620 say they have incurred expenses relating to the loss of a job in the last three years. This compares with just 19 percent of those with scores over 700. Unsurprisingly, it appears much easier to maintain good credit if you are not coping with extended unemployment.

It makes little sense to say that someone is not a good candidate for a job because they are still coping with the expense of a costly family medical emergency several years ago. Yet this may be exactly the type of situation that a blemished credit history indicates: having unpaid medical bills or medical debt is cited as one of the leading causes of bad credit among survey respondents who say their credit is poor, with more than half citing medical bills as a factor. Households that report low credit scores are more likely to have medical debt on their credit cards than those with good credit. In addition, more than half of those with self-reported credit scores under 620 also have medical debt that’s not on their credit cards. A lack of health coverage is also a factor in poor credit: in our sample, households that include someone without health coverage are more than twice as likely to report that their credit score has declined a lot in the past three years.

Our findings about the prevalence of medical debt parallel those of previous studies. The Commonwealth Fund found that in 2007, 41 percent of working-age adults had accrued medical debt or reported a problem paying their medical bills. Similarly, a Federal Reserve study found that the credit reports of about 15.7 percent of middle-income people and nearly 23 percent of low-income people included collection accounts for medical debt. The vast majority of these individuals had lower credit scores as a result. The most startling statistic is that Federal Reserve Board researchers found that 52 percent of all accounts reported by collection agencies consisted of medical debt. Poor credit tells a story of medical misfortune far more convincingly than one of poor work habits.

Finally, raising children appears to have a negative association with credit scores, as households with one or more children at home are more likely to report poor credit. Twenty-three percent of indebted households raising children describe their credit scores as poor, compared to 12 percent among indebted households without kids. These numbers correlate to reported scores: 25 percent of households who have children at home and know their credit scores within a range classify their credit score below 620, compared 13 percent of households without children at home. Instead, households without children are more likely to have scores at the top of the ranking, with 17 percent of these households reporting a credit score of 800 or higher, compared to 5 percent in this category among indebted households with children living at home.

People of color are disproportionately likely to report poor credit.

Our survey found that households of color are at a serious disadvantage when it comes to credit history. While the majority of low- and middle-income white households with credit card debt report good or excellent credit, the opposite is true for African Americans. Sixty-five percent of white households in our sample describe their credit scores as good or excellent, much higher than the 44 percent of African American households who identify in the good or excellent categories. In contrast, over half of African American households fall into the range of fair and poor credit. Among households with credit card debt who know their credit score within a range, just 15 percent of white households in our sample have credit scores below 620, compared to more than a third of African American households. Most white households (59 percent) report scores of 700 or above, displaying strong credit, while less than one quarter of African Americans (24 percent) are able to attain the same high credit rating status. Our findings are consistent with previous research on the racial gap in credit scores, including studies by Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Trade Commission and the Brookings Institution.

The credit histories of Latinos and African Americans have suffered as a result of discrimination in lending, housing and employment itself. This legacy of discrimination has also resulted in a large and growing racial wealth gap: in 2009, the median wealth of white households was 20 times that of black households and 18 times that of Hispanic households. With substantially less wealth to draw on, households of color are forced to borrow to deal with emergencies at times when white households can fall back on their savings. At the same time, predatory lending schemes in the last decade targeted communities of color, compounding historic disparities in wealth and assets, and leaving African-Americans, Latinos, and other people of color at greater risk of foreclosure and default on loans. Employment credit checks can perpetuate and amplify this injustice, translating a legacy of unfair lending into another subtle means of employment discrimination.

The racially discriminatory potential of employment credit checks is the key reason that civil rights organizations such as the NAACP, the National Council of La Raza, the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, and the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights under Law have publicly opposed the use of employment credit checks. In general, civil rights law mandates that employers justify the appropriateness of an employment practice if it creates a disparate impact on a group historically subject to workplace discrimination. Although specific cases of discrimination can be difficult to prove, some high-profile suits have been won. For example, the Department of Labor won a case in 2010 against Bank of America in which the bank was found to have discriminated against African-Americans by using credit checks to hire entry-level employees. A significantly higher proportion of African-American candidates (11.5 percent) were excluded because of the credit check than white candidates (6.6 percent).

Credit report errors are commonly cited as contributors to poor credit.

The frequency of errors in credit reports is another reason why credit reports are not reliable for employment. In our sample,12 percent of respondents who say that they have poor credit assert that errors in their credit report were a contributing factor. This rate of errors should be considered in the light of other major research on the subject. In February 2013, the Federal Trade Commission released the results of a comprehensive study of credit reporting errors, finding that 21 percent of American consumers had an error on a credit report from at least one of the three major credit reporting companies. Thirteen percent of consumers had errors serious enough to change their credit score. Ultimately about five percent of consumers (an estimated 10 million Americans) had errors that could lead to them paying more for credit products, such as auto loans, mortgages or credit cards.

However, the impact of credit reporting errors on employment is far more difficult to assess. Unlike lenders, employers do not look at a hard number like a credit score but rather subjectively assess the credit report’s list of accounts, subjectively deciding how much weight they give to elements such as foreclosures, late bills, or accounts in collection. What looks significant to one employer might not seem important to another. Thus a credit reporting mistake that is too small to make a difference in applying for credit might nevertheless stand out to an employer and cost someone a job.

Unfortunately, the safeguards included in the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) to protect job-seekers from credit reporting errors have not always proven to be sufficient. Although employers are required to notify job applicants before implementing a decision not to hire them based in any part on information from a credit report, employer compliance with this rule is difficult to monitor or enforce. As a result, job applicants may never realize that they were not hired because of their credit report and further may not realize that their credit report contains errors. In addition, the process of resolving credit reporting errors is deeply flawed, with the credit reporting agencies using an automated dispute resolution process that consumers describe as “Kafkaesque.”

A recent New York Times report illustrates how, in practice, credit reporting errors can stymie job searches in spite of the FCRA’s putative protections. The article tells the story of Maria Ortiz, who, after years of steady employment, spent nearly two years looking for work and was still unable to land a job despite assistance from a workforce development agency:

Ms. Ortiz was baffled by the repeated rejections until her caseworker checked her credit report. Everything made sense then: it showed that damaging, faulty information had been added to her report.

“It said I owe over $75,000 and that I have two cars,” Ms. Ortiz squealed. “I don’t drive! It said I have a mortgage. I don’t have a house!”

Quickly realizing that she needed to correct the false information, Ms. Ortiz and her caseworker sent letters to more than 20 companies and the credit bureaus to set straight which debts were veritably hers.

“I did have a lot of credit cards, but I always paid them on time,” she said. “I only had $500 of credit card debt, maybe less, and they weren’t outstanding.” Her credit reputation has since been restored, and she has achieved a nearly perfect TransUnion score, 798, but the blemish on her record took several months to reverse and was not without consequences.

In the summer of 2010, Ms. Ortiz went to a second interview for a position as a bank teller on Long Island.

“I thought I was going to get the job, but they ran my report and told me no,” she said. Despite the letters Ms. Ortiz had sent out, her report still reflected incorrect information.

Ms. Ortiz’s story is instructive. It is impossible to know how many of the jobs she applied for over the years rejected her as a result of incorrect credit information while the employers simply did not provide the notification required under the FCRA. At minimum, it appears that the bank teller position did not provide the required opportunity to address the already-disputed errors in her credit report before rejecting her for the job. Finally, it is revealing that even with the help of a dedicated case worker, it took Ms. Ortiz months to fix errors in her credit report. As a practical matter, disputing an error can be a time-consuming, nearly impossible three-party negotiation between the credit bureau, the creditor and the individual—a negotiation for which the outcome is ultimately controlled by the sometimes arbitrary decision of the agency.

Policy Recommendations

Employment credit checks are an illegitimate barrier to employment, often for the very job applicants who need work the most. Many government entities, from local city councils to federal agencies, can take action to reduce the prevalence of employment credit checks and otherwise mitigate their negative impact.

We recommend the following:

City and State Governments

Pass legislation banning employment credit checks.

As of February 2013, eight states (California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Oregon, Vermont and Washington) have passed legislation to restrict the use of credit checks in employment and dozens of additional cities and states have introduced bills to do so. As the New York Times editorial board noted, “the interest around this issue shows that more law makers are starting to realize how this unfair practice damages the lives and job prospects of millions of people.” At the same time, however, these laws include numerous exemptions that allow certain employers to continue conducting credit checks even when there is no evidence that credit history is relevant to job performance. Accordingly, states that have already restricted employment credit checks should tighten their laws and eliminate exemptions. Other states and cities should take action to ban credit checks.

Stop government use of employment credit checks for its own hiring.

Before the state of Connecticut enacted its restrictions on employment credit checks, the city of Hartford led the way by eliminating credit checks for all municipal hiring. This is an excellent policy choice for cities and counties that are prohibited by state law from regulating private employers: by changing their own hiring practices, these jurisdictions can directly remove a barrier to public employment for citizens with impaired credit and send a message to private firms about the shortcomings of employment credit checks.

U.S. Congress

Pass legislation banning employment credit checks.

Representative Steve Cohen introduced the Equal Employment for All Act (H.R. 645). This legislation would amend the Fair Credit Reporting Act to prohibit the use of employment credit checks. This legislation was endorsed by The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, the NAACP, the National Council of La Raza, the National Partnership for Women and Families, the AFL-CIO and dozens of other civil rights, employment, and consumer advocacy organizations. The bill should be passed and signed into law.

Federal Agencies

Stop using credit checks in federal agencies’ own hiring.

Currently many federal agencies require credit checks as part of their determination of suitability for federal employment. Credit checks are supposed to be used as a means to ascertain deliberate financial irresponsibility, but in practice job applicants with poor credit due to any circumstance may be disqualified from employment. Federal agencies should stop using credit checks in their own hiring, with possible exceptions for positions requiring national security clearance.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

Require credit reporting agencies to improve accuracy.

The CFPB should use its new supervisory authority to ensure that credit reporting agencies reduce the incidence of errors on credit reports and improve their dispute resolution procedures. While these measures will not directly prevent the use of credit checks for employment purposes, they will reduce the chances that job applicants subject to credit checks are denied a job due to errors on their reports.

Require credit reporting agencies to remove information about medical debt, disputed accounts, and unsafe products from credit reports.

While there is little or no evidence that any data on personal credit history is relevant to employment, some categories of information on credit reports are particularly pernicious because they represent disputed information, invasions of medical privacy, and/or a repeat discrimination against those who have already been victimized by predatory lending.

Medical debt, disputed accounts, and defaults on unsafe financial products not only fail to predict employment behavior but also may also fail to predict a consumers’ behavior as a borrower.

Accordingly the CFPB should act to ensure that:

- Disputed accounts are excluded from credit reports, or marked as “disputed.”

- Medical debt—including debt turned over to collection agencies—is excluded from credit reports.

- The CFPB should develop standards for the reporting of defaults on financial products they deem to be “unsafe,” such as extremely high-interest loans. If defaults on unsafe products are not predictive of future payment risks for safe products, they should be excluded from credit reports.

Federal Trade Commission

Enforce the Fair Credit Reporting Act’s requirements on employers.

The FCRA mandates that employers obtain a job applicant’s authorization before requesting a credit report and notify job applicants if the employer plans to take adverse action (such as rejecting a job application or denying a promotion) due in any part to information on a credit report. As noted before, compliance with these provisions is difficult to oversee, since without notification an employee would have no way of knowing that they were rejected due to their credit history. Nevertheless, the Federal Trade Commission should aggressively pursue tips and seek out ways to enforce the law.

Continue to enforce the Fair Credit Reporting Act’s requirements on companies that sell credit reports and other consumer data to employers.

In 2012 the FTC settled charges with online data broker Spokeo for marketing consumer information to human resources people and recruiting agencies in ways that violated the FCRA. The FTC should continue to enforce the law vigorously.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Issue guidance prohibiting the use of credit history for employment purposes.

Our research is just the latest study to demonstrate that people of color are disproportionately likely to report poor credit, strongly suggesting that employment credit checks have a disparate impact on African Americans and other groups protected by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Indeed, the Department of Labor won a case against Bank of America in which the bank was found to have discriminated against African Americans by using credit checks to hire entry-level employees. Since little or no evidence exists that credit history is meaningfully predictive of job performance for any position, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) should issue formal guidance that bars the use of credit history for employment purposes.

Conclusion: Employment credit checks illegitimately obstruct access to jobs

Our research supports the contention that employment credit checks can create an untenable catch-22 for jobseekers: they are unable to secure a job because of damaged credit and unable to escape debt and improve their credit because they cannot find work. But the fundamental unfairness of the situation goes a step further: we find that poor credit history is associated with factors such as race, unemployment status, parenting responsibilities, and medical debt that have not been justified as reasons to make hiring decisions and – in the case of racial discrimination in hiring – are illegal in the United States. Accordingly, we conclude that credit history illegitimately obstructs access to employment. Many Americans seem to agree: when we asked our sample of low- and middle-income workers with credit card debt whether employers should be able to look at a job applicant’s credit report, 75 percent said no.