Introduction

In Massachusetts, the very rich are getting much richer, the poor are getting poorer, and those in the middle are stagnating. Workers in Massachusetts, as in the nation generally, have seen little to no wage growth since the 1980s. From 1979 to 2014, Massachusetts households at the 20th percentile averaged a 0.2 percent decline in income annually. The median household averaged only a 0.5 percent increase annually. This increase is better than a decline, but it is very close to no growth. The richest 1 percent of households, however, had a strong 4.3 percent average annual income growth. This trend has made Massachusetts the 6th most unequal state in terms of the ratio of income of the top 1 percent to the bottom 99 percent.

An important factor behind these income trends is the slow and steady decline in “good jobs” that we have seen nationally. Good jobs pay a wage that can support a family and have benefits that help a family build wealth. Families need wealth or assets to have long-term economic security; wealth allows them to weather financial emergencies and to invest in their future.

Public-sector jobs in Massachusetts are more likely than private-sector jobs to be good jobs that provide a family-supporting income and wealth-building benefits, so they need to be preserved. At a time of growing economic inequality, jobs in the public sector help preserve the middle of the income distribution—the middle class. Public-sector jobs also help build strong communities because Bay State public-sector workers are more likely to be long-term community residents, increasing neighborhood cohesion, strengthening civic engagement, and reducing crime.

Massachusetts, like the nation as a whole, needs to maintain the good jobs that it has, and enact policies to create more good jobs. Dismantling public-sector jobs is a step in the wrong direction, a step that will hurt Massachusetts families and communities. Policymakers should keep the public-sector jobs the state has and use them as a guide for developing policies to make more jobs in the private sector good jobs.

Key Findings

- Good Job Advantage. For white, Latino, African-American, and Asian-American workers, public-sector employment increases their odds of having a good job—one that provides a wage that can support a family and benefits that help the family build wealth. African-American workers have the biggest increase in their odds.

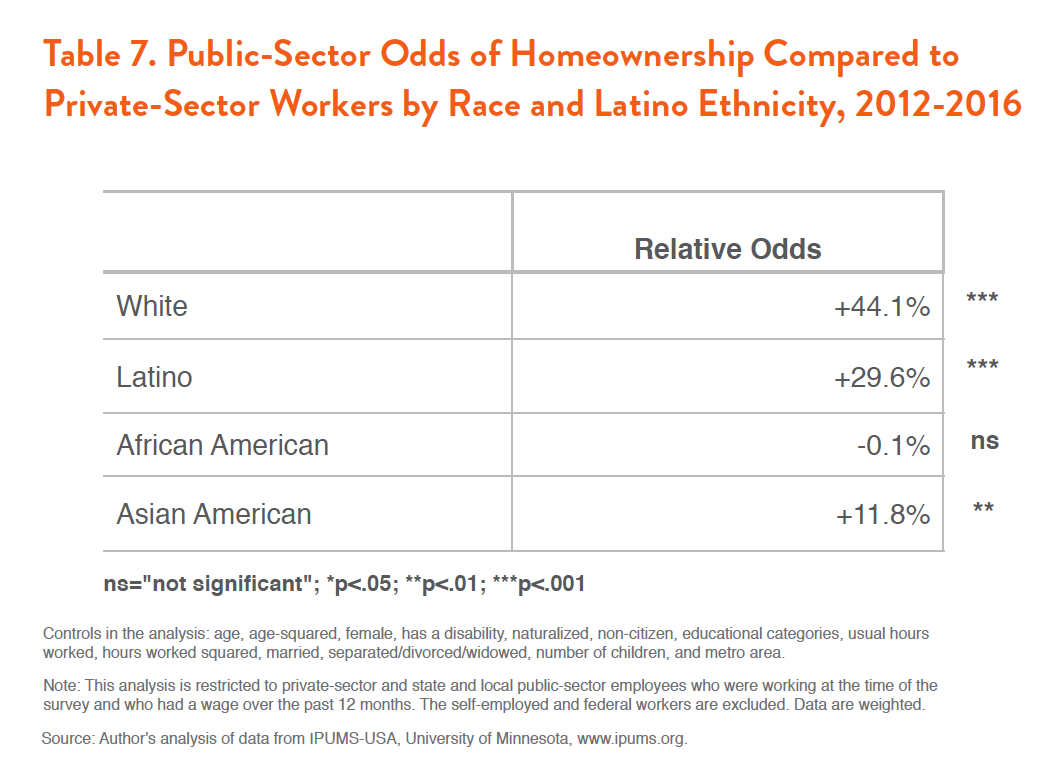

- Homeownership Advantage. White, Latino, and Asian-American public-sector workers are more likely to be homeowners than their same-race peers in the private sector, after controlling for differences in backgrounds. African-American public-sector workers are equally likely as black private-sector workers to be homeowners.

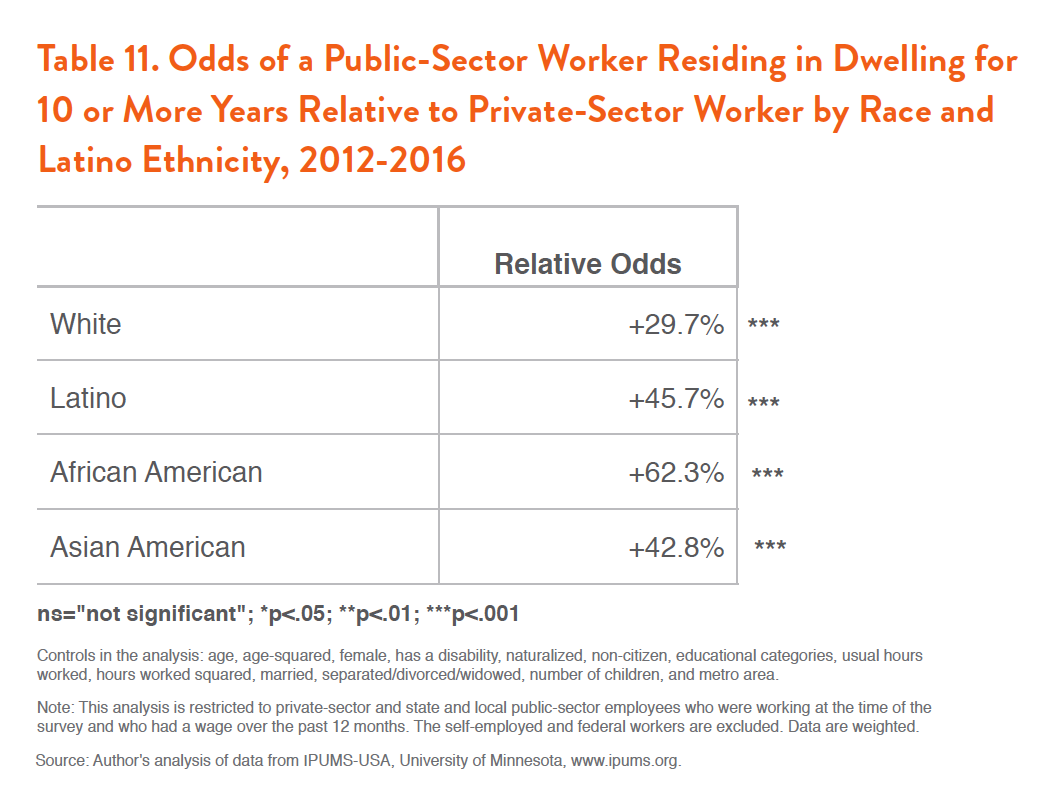

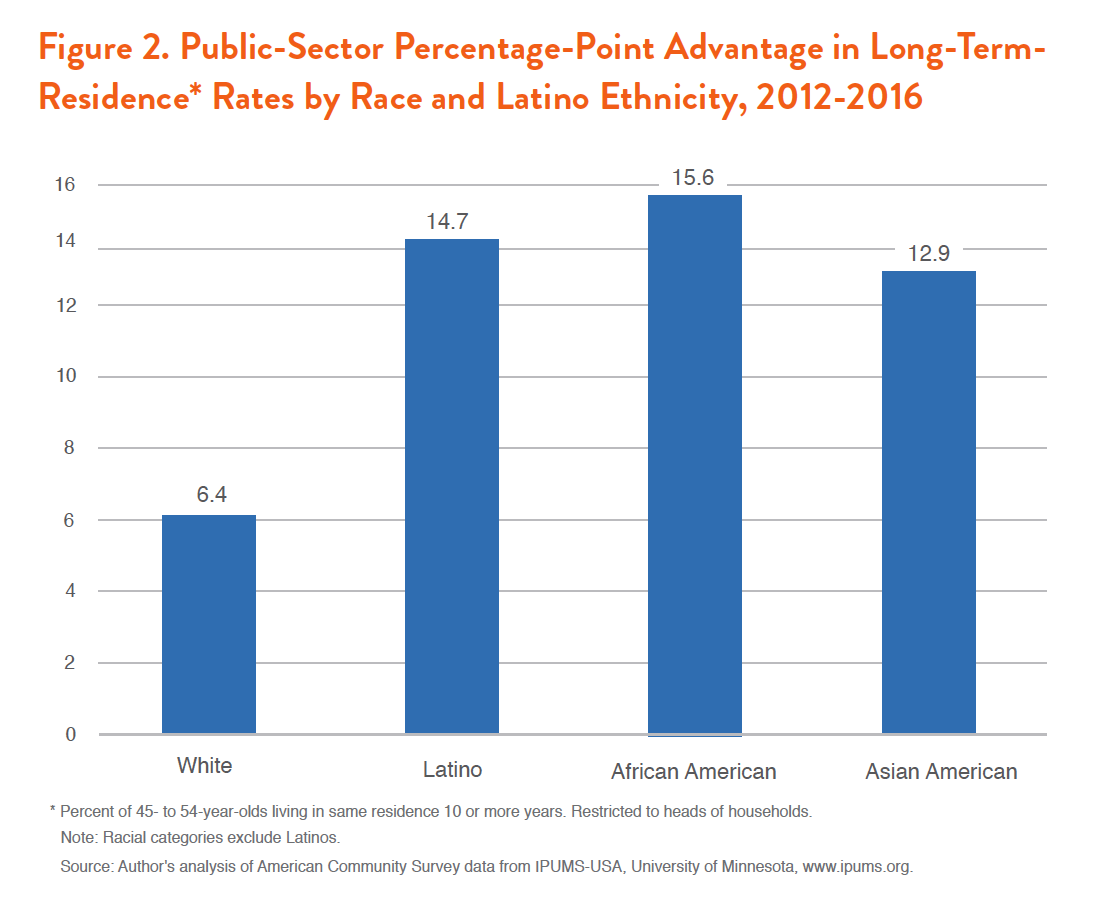

- Community Stabilization Advantage. Public-sector workers of all racial and ethnic groups are more likely to live for 10 or more years in the same community. This residential stability contributes to reducing crime, building neighborhood cohesion, and increasing civic participation.

- Equality Advantage. The public sector is better than the private sector at decreasing economic and racial inequality and strengthening Massachusetts communities. The public sector should serve as a guide for creating good-jobs policies in the private sector.

The Data and Analysis

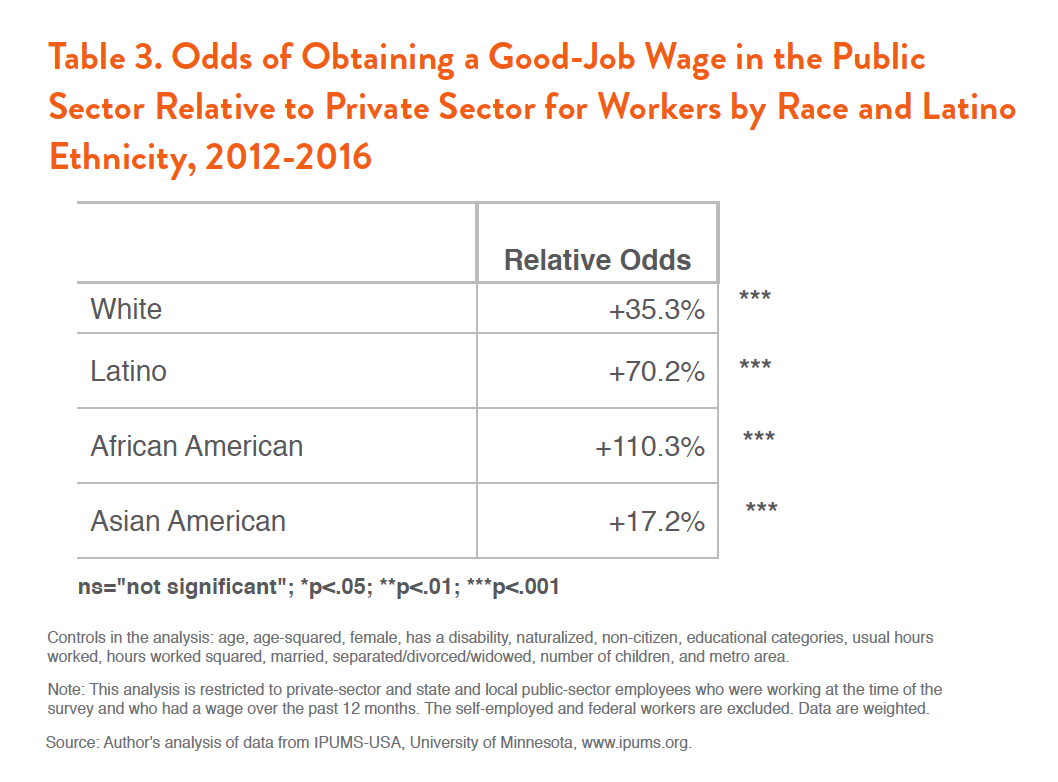

This analysis of the economic benefits of public-sector jobs in Massachusetts is based on comparisons of private-sector and state and local public-sector workers in the data from the 2012-2016 American Community Survey. The analysis also examines workers by race and Latino ethnicity. The American Community Survey is a nationally representative survey of the American population with a sample size of about 3.5 million per year. The data used is a 5-year pooled sample. This large sample size provides enough cases for a detailed analysis of relatively small populations—Massachusetts public-sector workers by race and Latino ethnicity. While the sample size is a strength of the American Community Survey, the weakness is that there are few detailed economic measures. This weakness places limits on some of the analyses, which are noted in the context of the specific analyses.

The analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we examine what are the differences, and second, we explore possible reasons for why are there differences. The results on a specific economic measure are presented by racial or Latino ethnic group to assess differences. Then, a linear or logistic regression is performed, controlling for background characteristics such as age, gender, and educational attainment, to determine if the relationships are due to differences among these background characteristics. This analysis allows us to see if we can eliminate these background characteristics as the cause of any differences we might find. See the tables for details on the control variables.

Are Public-Sector Jobs Good Jobs?

A good job has, at minimum, a good hourly wage and good benefits. We approximate the hourly wage and health insurance data from the American Community Survey to obtain a rough sense of which sector is more likely to have good jobs.

Good-Job Wages

A “good-job wage” can be understood as a wage that can support a family. More specifically, it can be defined as a wage that would yield at least 60 percent of the median household income for a full-time, full-year worker. This is a wage standard that is sometimes used in cross-national poverty comparisons. To better reflect the local cost of living, the Massachusetts median household income will be the benchmark instead of the national median. In 2016, the minimum for a good-job wage for Massachusetts would be $20.47 per hour or $42,572.40 annually for a full-time, full-year worker.

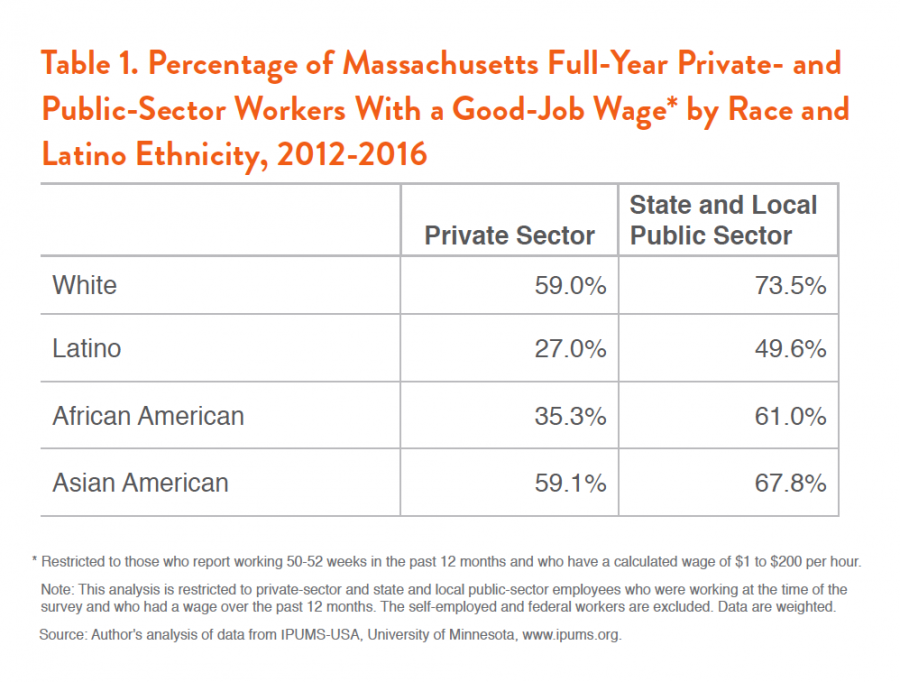

Table 1 shows the good-job-wage rates for private- and public-sector workers who work full-year. For all 4 racial and ethnic groups, the rate of good-job wages is higher in the public sector than in the private sector. The good-job-wage rates for Latino and African-American workers in the private sector are particularly low. Only about a quarter (27 percent) of Latino and a third (35.3 percent) of African-American workers have good-job wages in the private sector. However, almost two-thirds of white and Asian-American workers (59 percent and 59.1 percent respectively) in the private sector have good-job wages.

Latino and African-American good-job-wage rates in the public sector are nearly double that of the private sector. Half (49.6 percent) of Latinos in the public sector earn a good-job wage versus 27 percent in the private sector. In the public sector, 61 percent of black workers earn good-job wages, 25.7 percentage points higher than in the private sector. For white public-sector workers, 73.5 percent have good-job wages, 14.6 percentage points higher than in the private sector. Asian-American workers in the public sector have a good-job-wage rate of 67.8 percent, 8.7 percentage points higher than in the private sector.

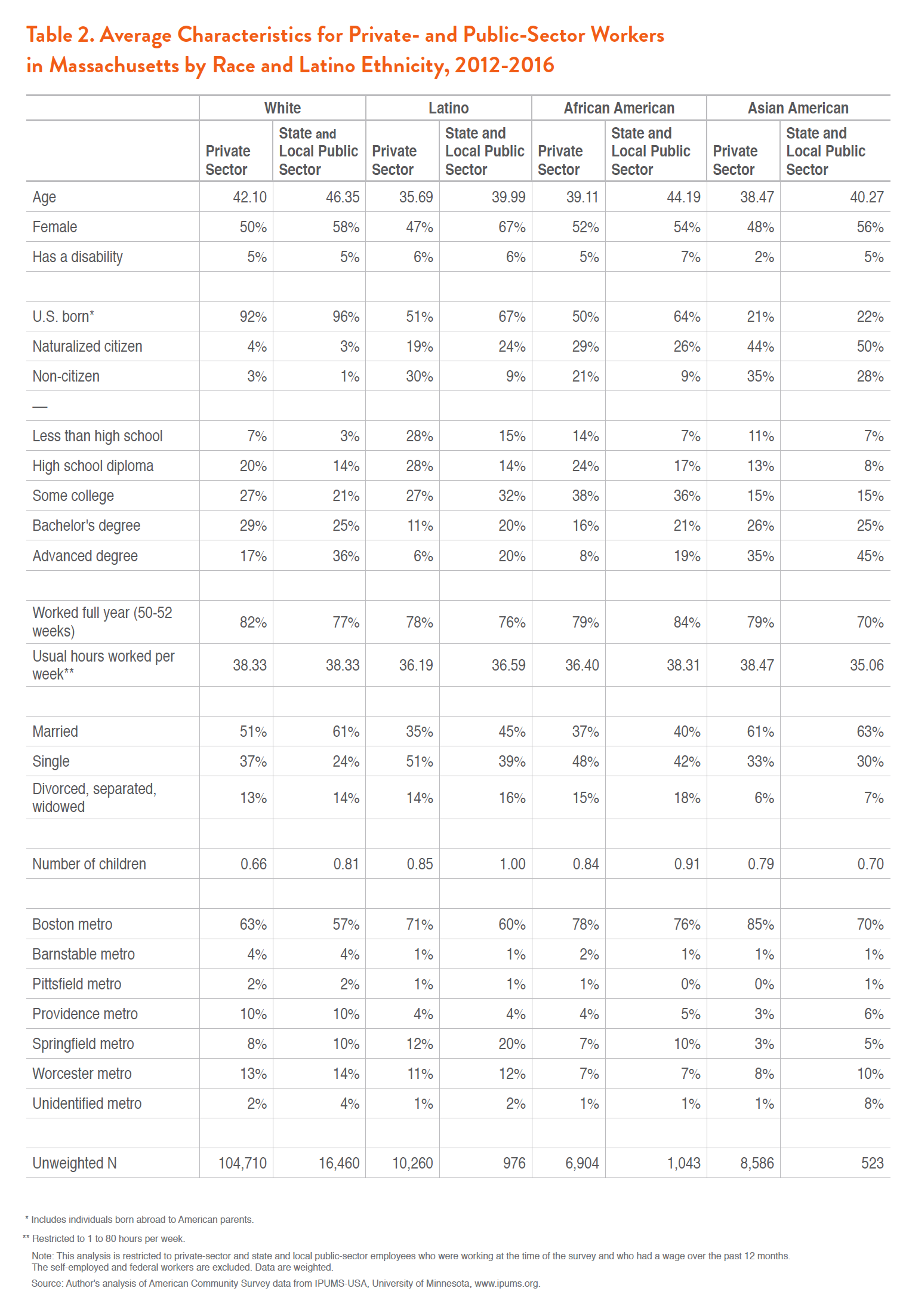

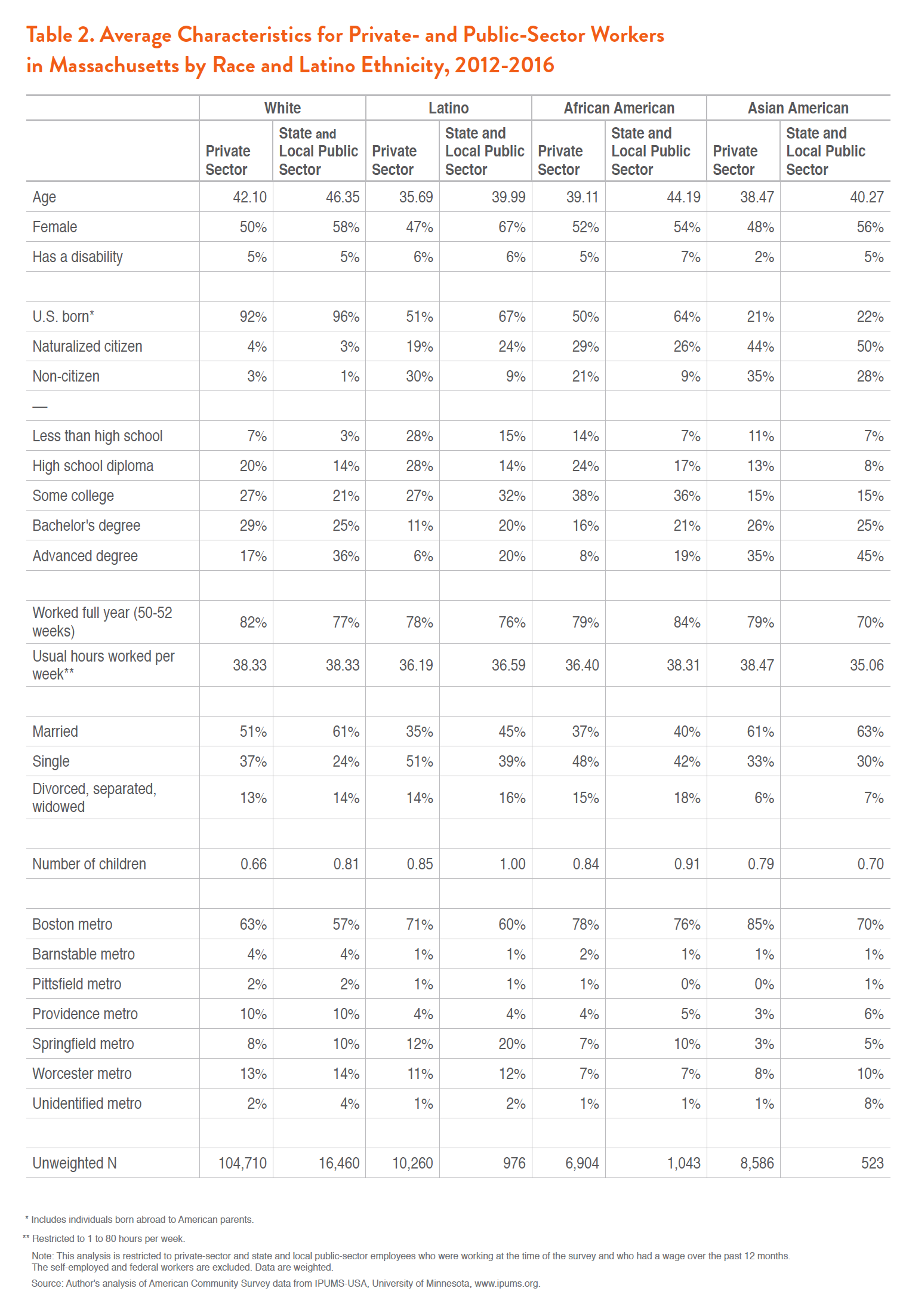

These rates, however, do not take into account important differences between private-sector and public-sector workers. Public-sector workers are more likely to have college degrees on average than private-sector workers, as Table 2 shows, and workers with higher degrees tend to earn more. Public-sector workers are also older than private-sector workers. Older workers tend to be further along in their careers and have higher earnings as a result. Are public-sector workers more likely to have good-job wages because of these characteristics?

On the other hand, public-sector workers are disproportionately female, and women tend to be paid less than men. Is the public-sector advantage in good-job wages even stronger when we take this into account?

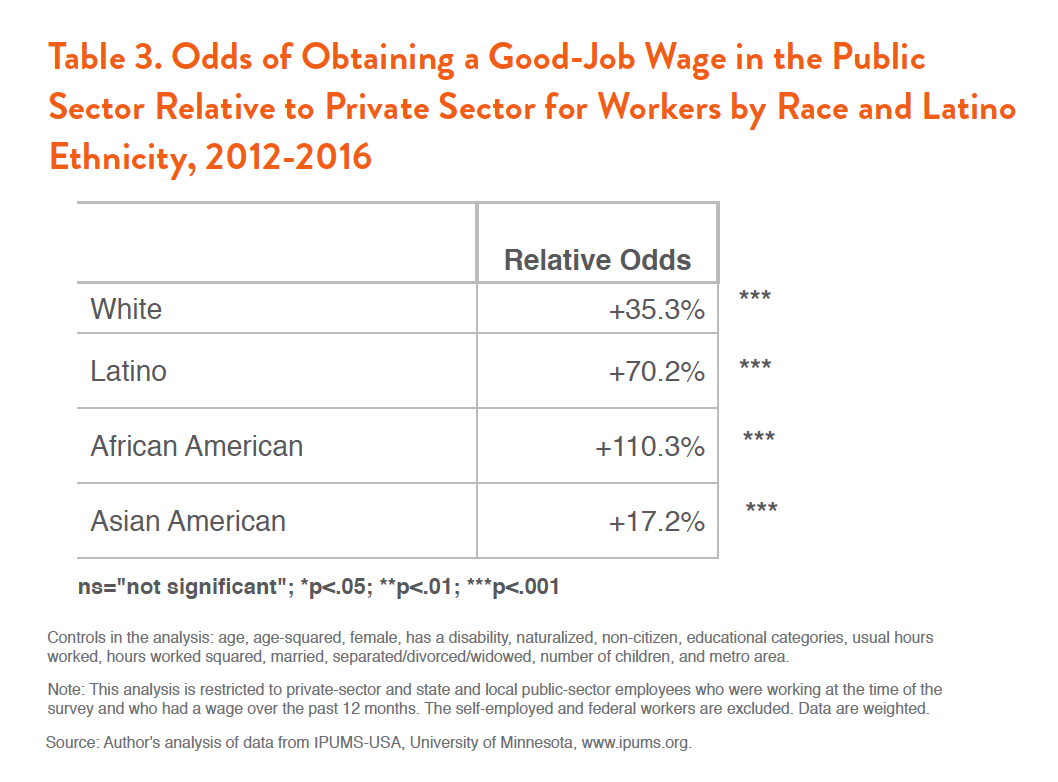

To remove the impact that these and other characteristics have on public-sector workers’ odds of having a good-job wage, we must take into account or control for educational attainment, age, gender, and other relevant average differences between public-sector and private-sector workers. After controlling for differences, for all groups, public-sector employment is still found to increase the odds that individuals will have a good-job wage, as Table 3 shows. The impact is largest for African Americans, who more than double their odds (an increase of 110.3 percent) of attaining a good-job wage by working in the public sector. Latinos also have a strong increase (70.2 percent) in their odds of obtaining a good-job wage by working in the public sector. White and Asian-American workers also experience significantly increased odds (35.3 percent and 17.2 percent respectively) of having a good-job wage by working in the public sector.

Health-Insurance Coverage

Public-sector workers are more likely to have access to health insurance and retirement plans than private-sector workers. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports, for New England in 2017, that 88 percent of public-sector workers had access to medical care as an employee benefit. In the private sector, the rate was 67 percent. For retirement benefits, 86 percent of public-sector workers had access, compared to 71 percent in the private sector. These results, in conjunction with the good-job wage findings above, suggest that public-sector workers are more likely to be employed in good jobs.

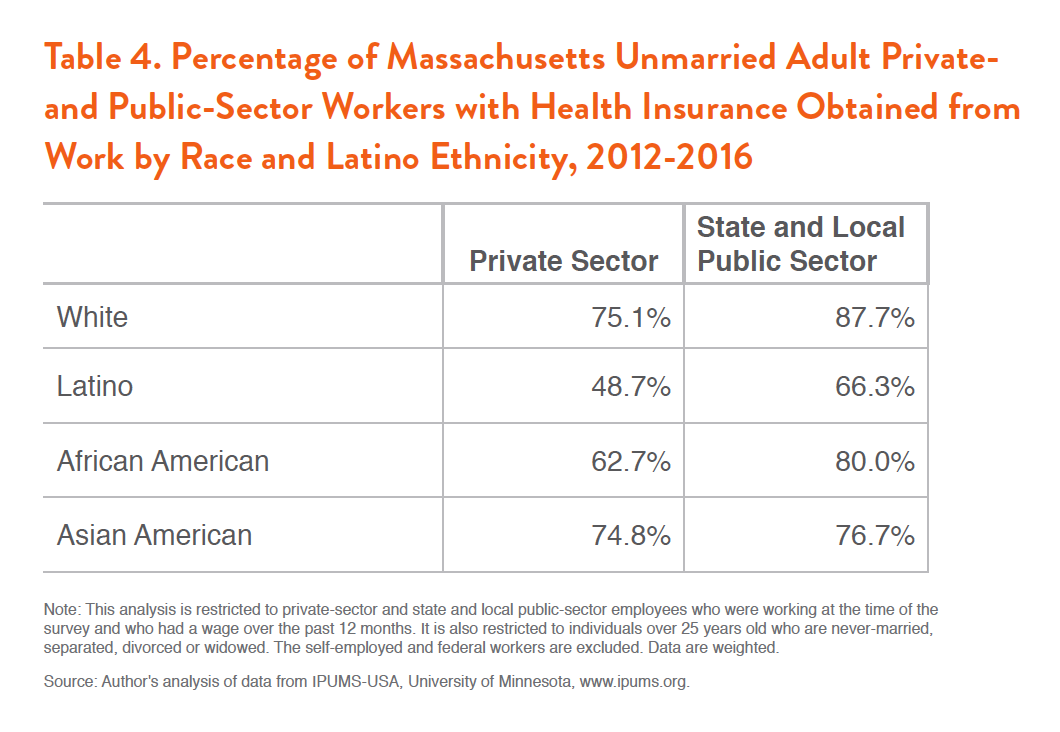

Unfortunately, the American Community Survey is not clear about whether health insurance obtained from work is due to the individual’s job or to a relative’s job. And it is not clear whether insurance is offered at work if the individual does not obtain coverage from work. Spouses are a possible source for health insurance coverage for adults, and parents are a possible source for individuals under 26. To reduce these sources of inaccuracies, the following analysis focuses on unmarried individuals over 25 years of age. These 2 restrictions minimize the likelihood that the individual obtains health insurance from a relative. They also reduce the sample size by about 70 percent. Luckily, the large sample size still leaves enough cases for analysis.

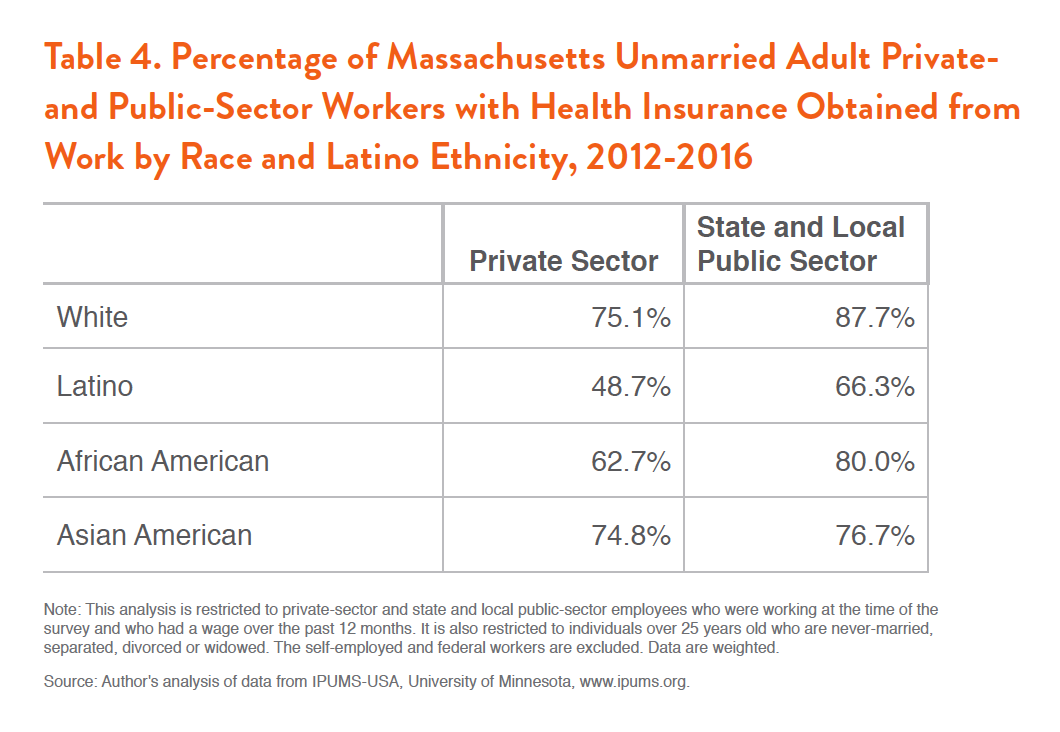

Table 4 shows the rate of health-insurance coverage from an employer or union for unmarried adults who are over 25 years old. As expected, public-sector workers are more likely to have coverage. Latino workers have the lowest rates, but they see the biggest percentage-point jump moving from the private to the public sector. About half (48.7 percent) of unmarried adult Latinos in the private sector have health-insurance coverage from work. Two-thirds (66.3 percent) have coverage in the public sector. African Americans have a similarly large rate jump. Nearly two-thirds (62.7 percent) of unmarried adult black workers in the private sector obtain health insurance from work. In the public sector, four-fifths (80 percent) of these workers do so. For unmarried adult white and Asian-American workers in the private sector, about three-quarters (75.1 percent and 74.8 percent respectively) obtain health insurance from work. For unmarried adult white workers in the public sector, nearly 9 in 10 (87.7 percent) have health-insurance coverage from their employer or union. Unmarried adult Asian-American workers in the public sector have only a small advantage over the private sector: Public-sector workers in this group have a rate of employer or union health insurance only 1.9 percentage points above the private-sector rate (76.7 percent versus 74.8 percent).

Good-Jobs Odds

Because of the limitations of the American Community Survey, we operationalize a good job as having 2 elements: a good-job wage and health insurance from work. (Since the American Community Survey does not have data on retirement accounts, retirement accounts cannot be included, as is often done in similar analyses.) This also requires us to restrict the analysis to unmarried adults over the age of 25, to have a more precise health-insurance measure.

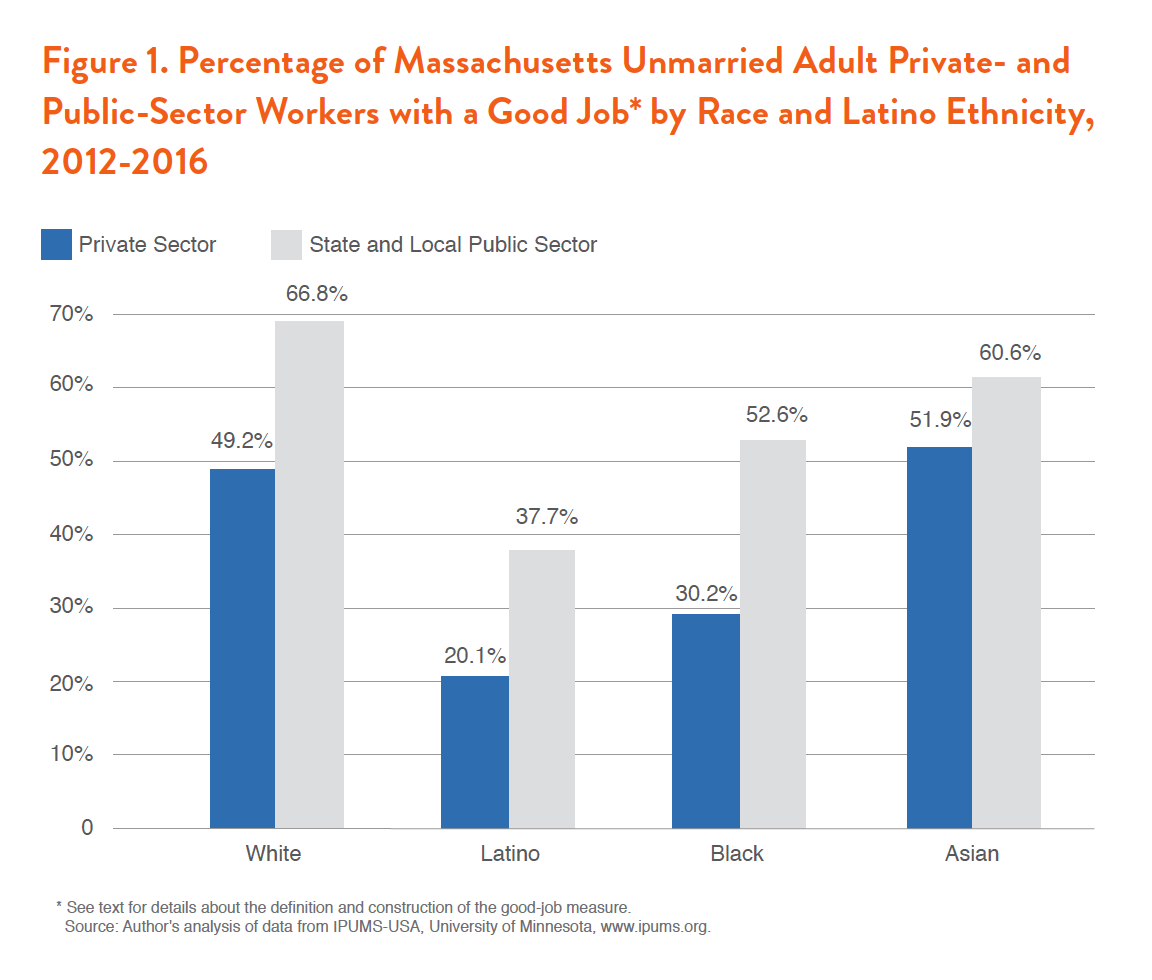

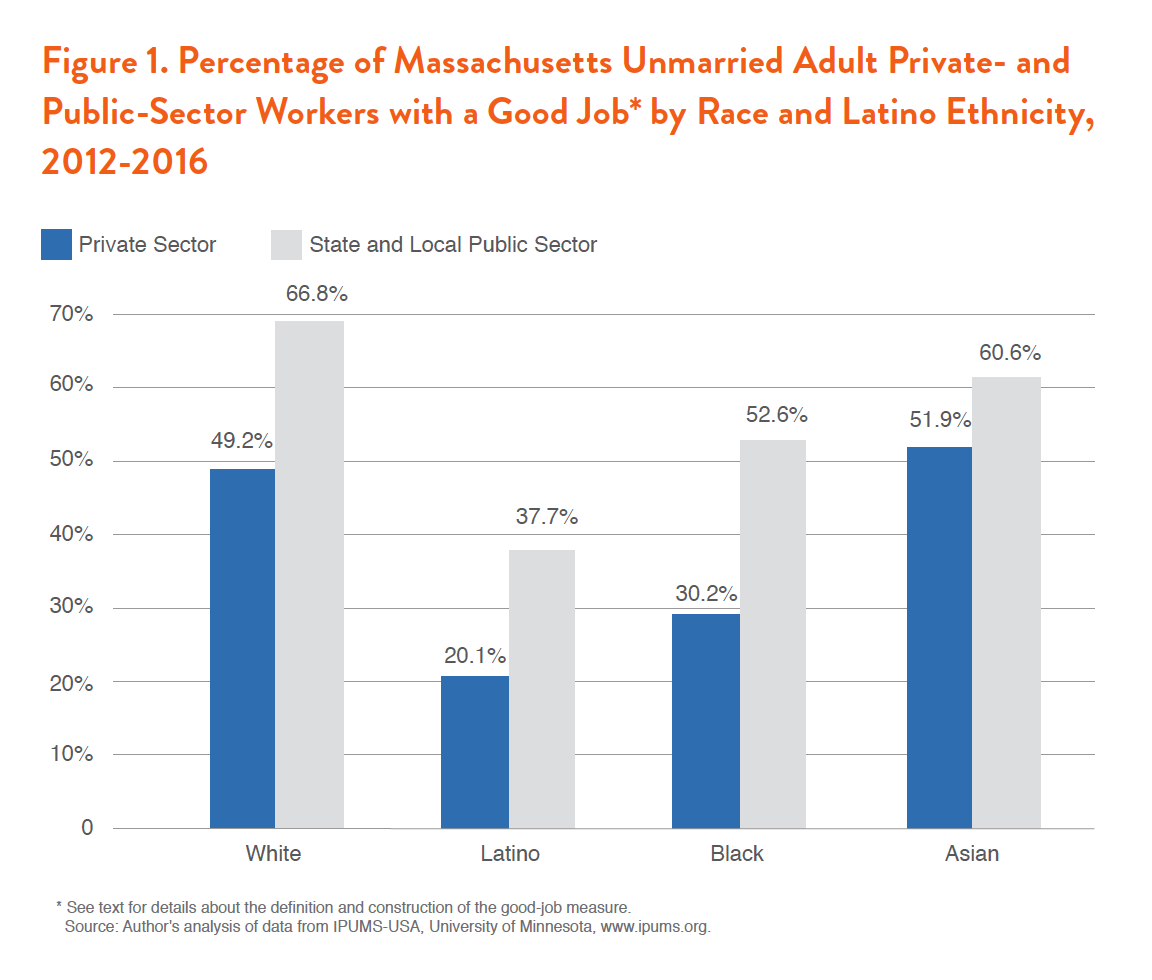

Given the findings on good-job wages and health-insurance coverage, the findings on good-job rates are not surprising; they are very similar to those for good-job wages. About half (49.2 percent and 51.9 percent respectively) of unmarried adult white and Asian-American workers are in good jobs in the private sector, as Figure 1 shows. In the public sector, two-thirds (66.8 percent) of these white workers and a little less than two-thirds (60.6 percent) of these Asian-American workers have good jobs. Only a fifth (20.1 percent) of unmarried adult Latino private-sector workers have good jobs. The good-job rate nearly doubles (37.7 percent) for these Latinos in the public sector. About a third (30.2 percent) of unmarried adult African-American private-sector workers are in good jobs, but half (52.6 percent) have good jobs in the public sector.

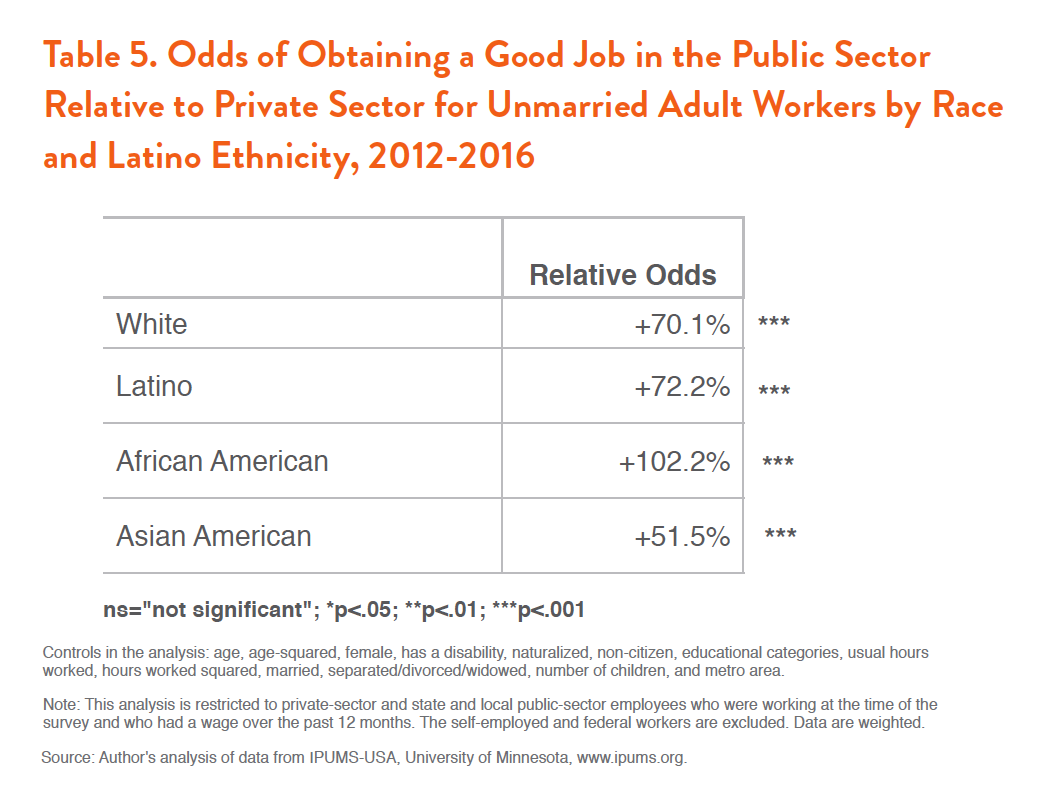

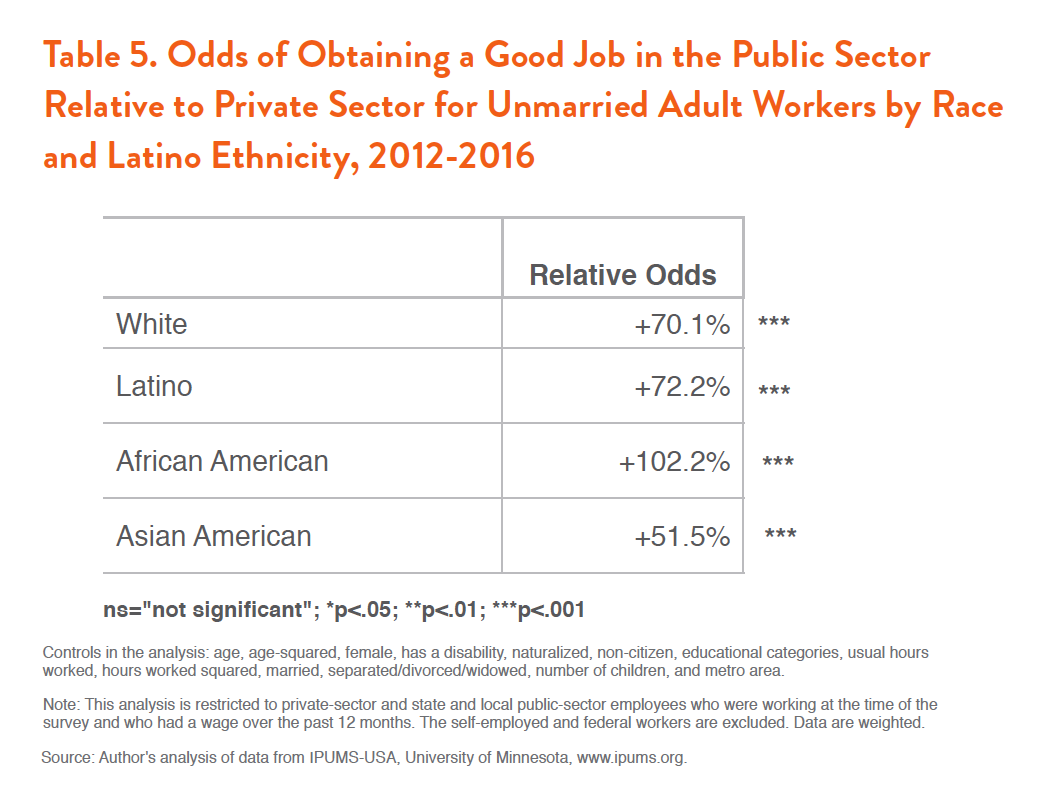

Is this good-job advantage due to public-sector workers being more likely to have college degrees or being older? By adding control variables, we can compare public-sector workers with private-sector workers who are similar with regard to educational backgrounds, age, and other characteristics. After controlling for differences in background characteristics, for all groups, public-sector employment increases the odds that individuals will have a good job, as shown in Table 5. The impact is largest for unmarried adult African Americans. They double their odds (an increase of 102.2 percent) of employment in good jobs by working in the public sector. Latino and white workers almost double their odds. Unmarried adult white and Latino people working in the public sector are both about 70 percent more likely to be in a good job than their peers in the private sector. Asian-American workers also experience significantly increased odds (51.5 percent) of being in a good job by working in the public sector.

For all racial and ethnic groups, public-sector employment increased their odds of being employed in a good job that provides good wages and benefits. Public-sector jobs help individuals escape poverty and provide for their families. A loss of public-sector jobs would mean the loss of good jobs in Massachusetts.

Do Public-Sector Jobs Help Families Build Wealth?

Wealth or net worth “is a superior indicator of financial status because it embodies the total economic resources available to its holder.” People draw on their wealth during financial emergencies, such as for unexpected repairs, an illness or a job loss. Wealth also helps individuals invest in their future, for instance by helping pay for a child’s college education or starting a business. Wealth provides a family with much broader economic security than income alone.

The American Community Survey allows us to assess whether or not an individual is a homeowner and it has information about the value of the home. “For all [racial] groups, the largest single contributor to total net worth is an owned home.” Additionally, those with home equity tend to have other sources of wealth. Homeownership therefore can give us useful, if incomplete, information about public-sector jobs and wealth.

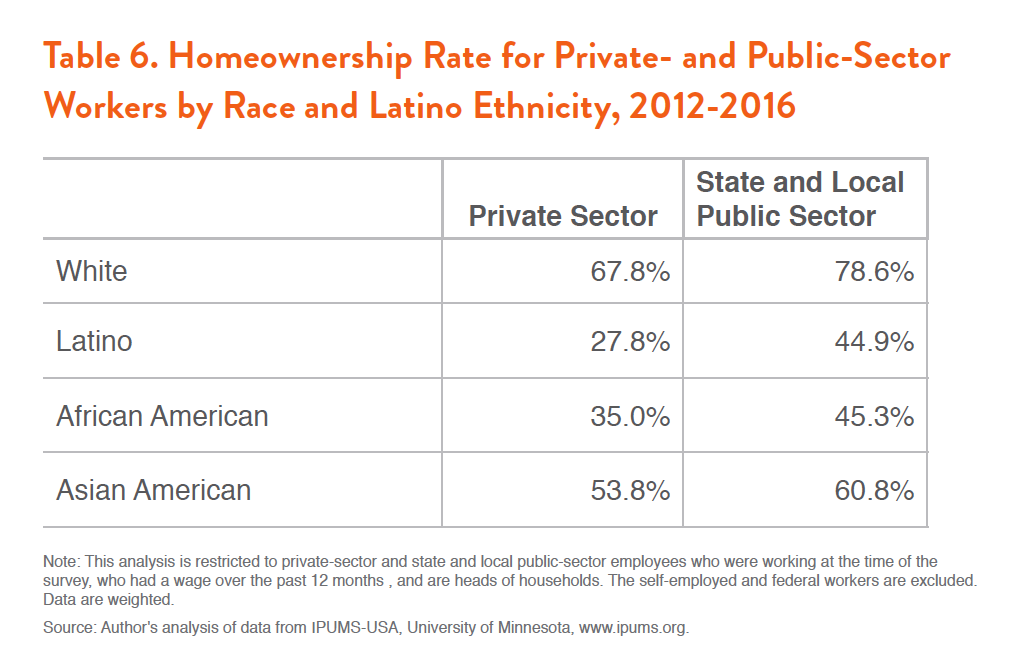

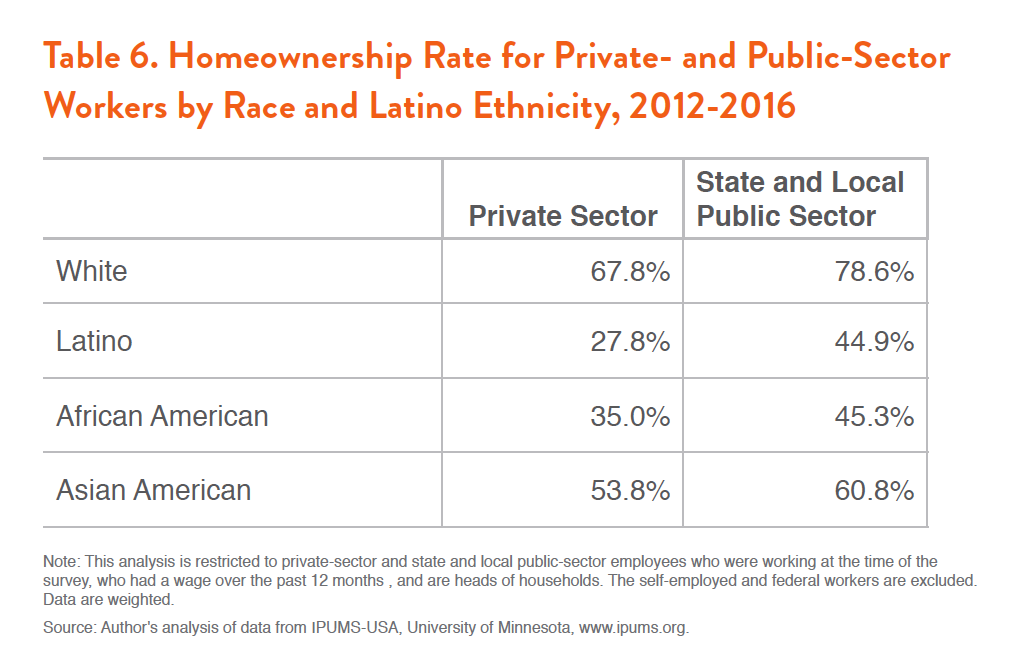

Table 6 shows that in homeownership, outcomes are better for the public sector than the private sector. Public-sector workers are more likely to be homeowners than private-sector workers of their same race or ethnicity. Two-thirds (67.8 percent) of white private-sector workers are homeowners, while more than three-quarters (78.6 percent) of white public-sector workers are. Nearly 3 in 10 (27.8 percent) Latinos in the private sector are homeowners, but over 4 in 10 (44.9 percent) in the public sector are homeowners. More than 3 in 10 (35 percent) African Americans in the private sector are homeowners, but more than 4 in 10 (45.3 percent) in the public sector are. More than 5 in 10 (53.8 percent) Asian Americans are homeowners in the private sector, but 6 in 10 (60.8 percent) in the public sector are homeowners.

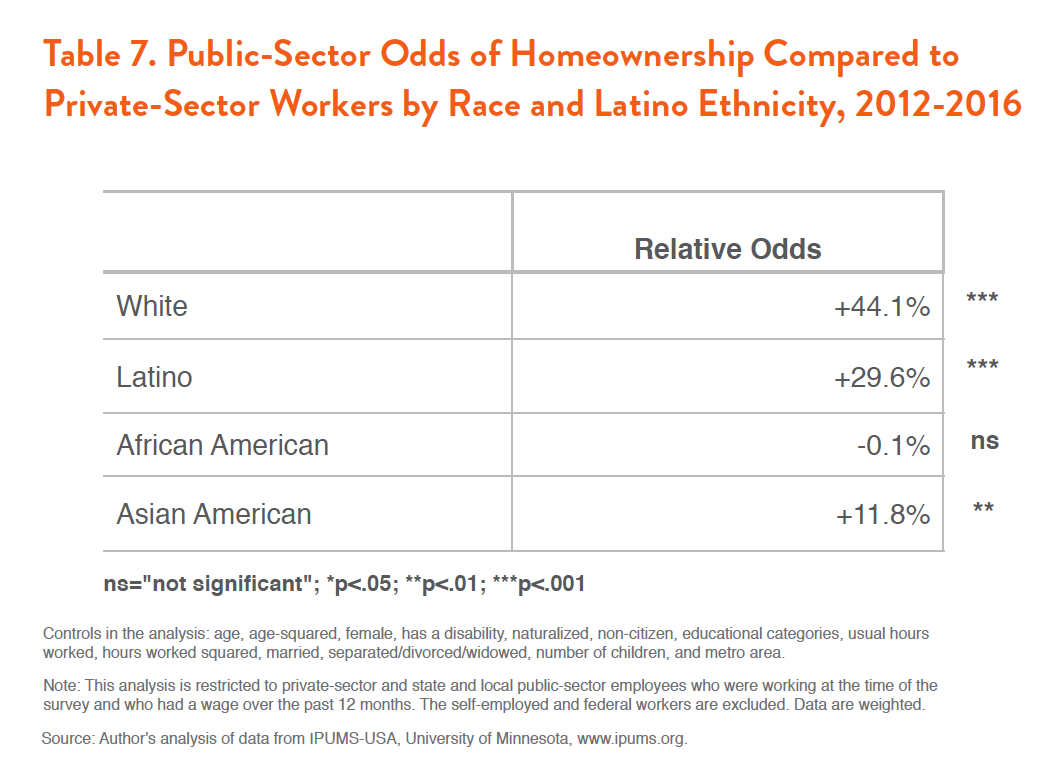

If we control for differences in age, gender, educational attainment, etc. among private-sector and public-sector workers, we find that white, Latino, and Asian-American workers still have a homeownership advantage in the public sector—but African Americans do not (see Table 7). African Americans in the public sector are equally likely as similar African Americans in the private sector to be homeowners. White public-sector workers, in contrast, are 44.1 percent more likely than their peers in the private sector to be homeowners. For Latinos in the public sector, the homeownership-odds advantage is 29.6 percent. Asian Americans in the public sector are 11.8 percent more likely to be homeowners than similar Asian Americans in the private sector.

Public-Sector Wealth versus Private-Sector Wealth

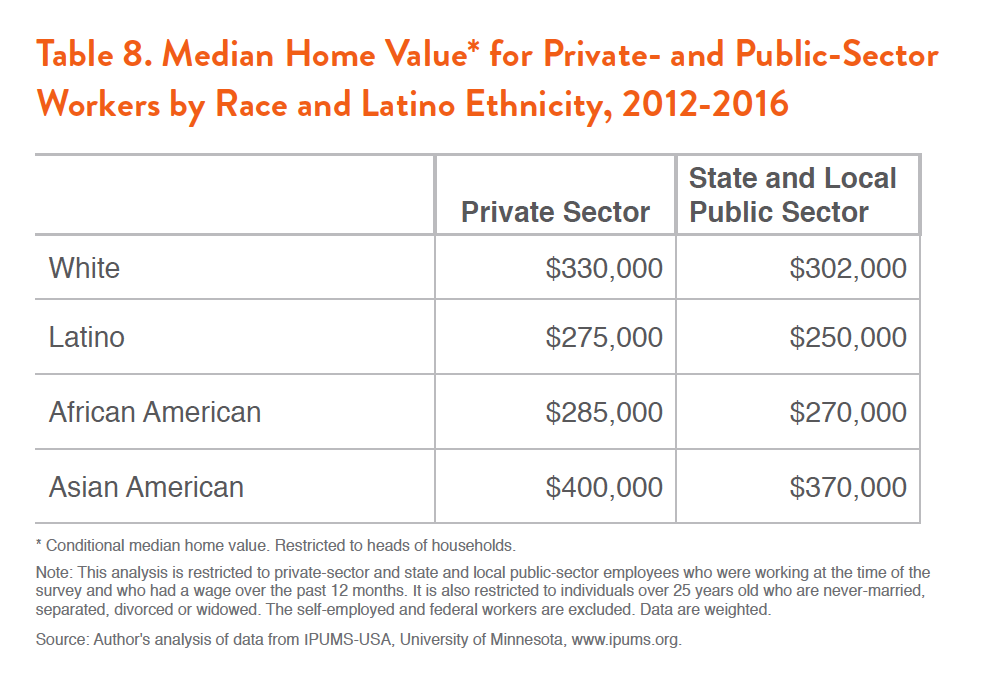

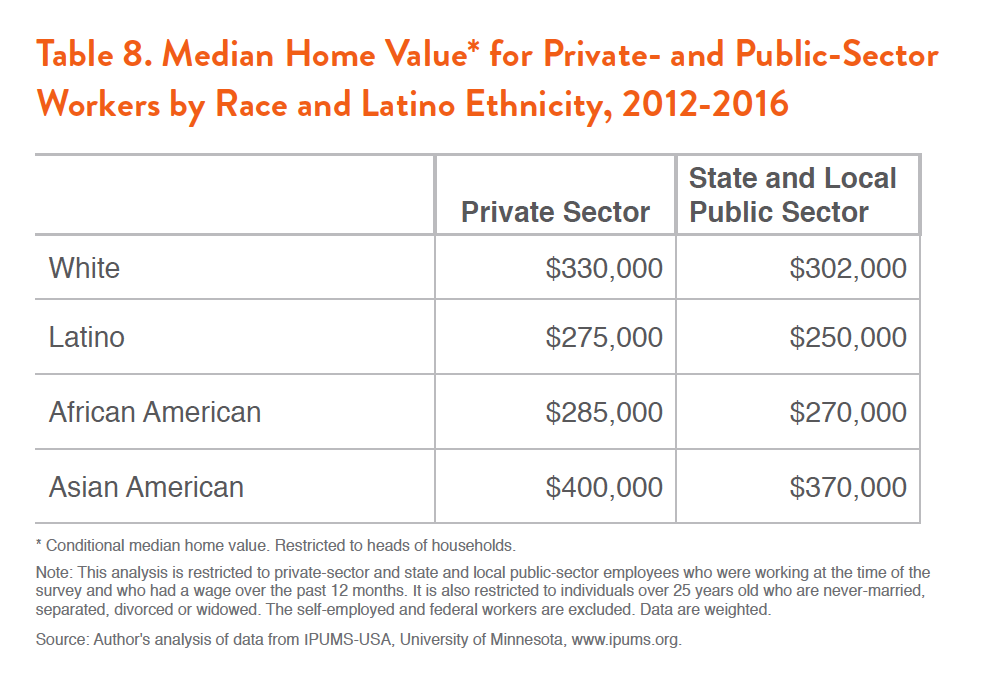

Table 8 shows that public-sector workers’ homes are on average worth less than the homes of private-sector workers. White private-sector workers have homes with a median value of $330,000, but white public-sector workers’ homes have a median value of $302,000, 8.5 percent less. For Latinos, the homes of public-sector workers are worth $25,000 or 9.1 percent less than those of private-sector workers. For African Americans, the public-sector workers’ homes are valued at $15,000 or 5.3 percent less. Asian-American public-sector workers’ homes are worth $30,000 or 7.5 percent less than the homes of Asian-American private-sector workers.

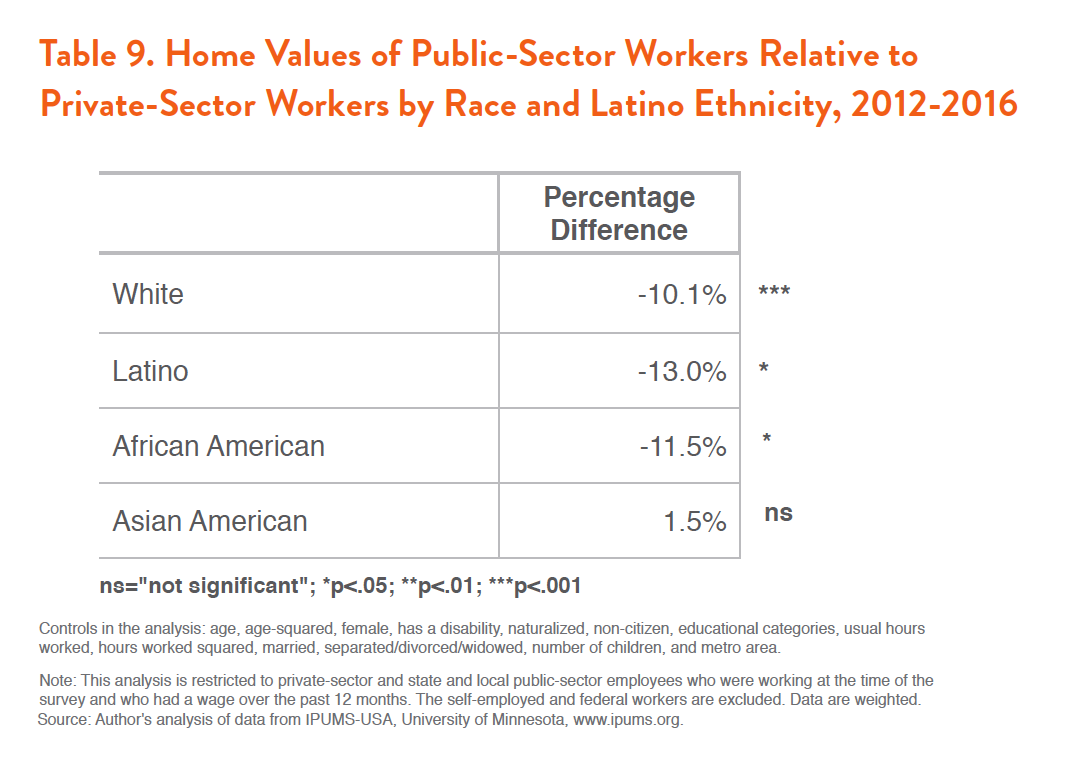

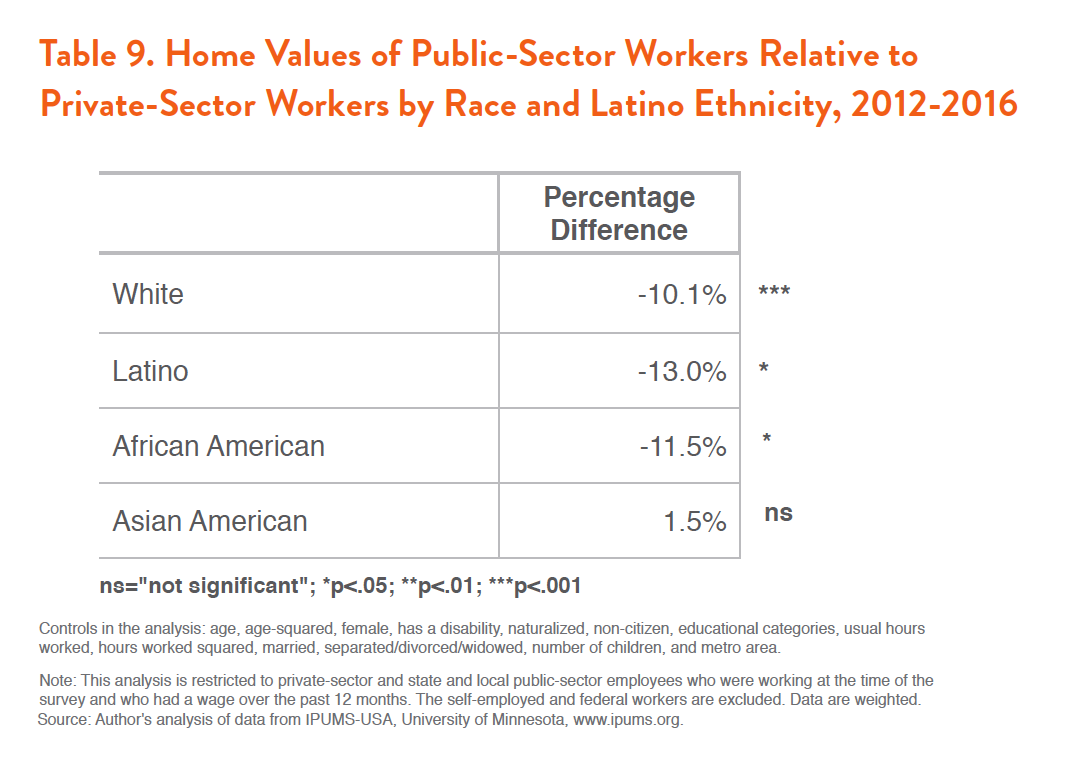

It is important to take into account differences in age, gender, and educational attainment between public- and private-sector workers, since they can affect economic outcomes. These characteristics may hide underlying similarities or may even be suppressing greater differences.

After controlling for background characteristics of the worker, we find that the homes of public-sector workers are valued less for all groups except for Asian Americans (Table 9). Thus, for Asian Americans, the measured differences between the characteristics of public-sector workers versus private-sector workers are able to explain the difference in the home values. This is not the case for the other groups. After controls, the homes of white public-sector workers are worth 10.1 percent less than the homes of white private-sector workers. For Latino public-sector workers, their homes are worth 13 percent less than the homes of their peers in the private sector. The homes of African Americans in the public sector are worth 11.5 percent less. For Asian Americans, however, the results are not statistically significant. Their homes are worth about the same whether they work in the private or public sector.

While the homes of public-sector workers are, on average, worth less than those owned by private-sector workers, public-sector workers are more likely to be homeowners than private-sector workers. In other words, public-sector jobs appear to help families build wealth through homeownership. Additionally, a home is only one asset, and thus provides an incomplete measure of net worth. Homeowners are more likely to have other assets, and public-sector jobs are more likely to provide wealth-building benefits such as health insurance and retirement accounts. Homeownership, assets correlated with homeownership, health insurance, and retirements accounts all provide wealth-building advantages for public-sector workers.

Public-Sector Jobs and Community Stability

So far, we’ve looked at the benefits of public-sector jobs to workers and their families, but it is also important to think about how these benefits can reverberate throughout communities. One measure that sheds light more directly on the potential community impact of public-sector jobs is the length of continuous residence a household has in a community. Residential stability is associated with positive outcomes at the neighborhood level including less crime, more social support and cohesion among neighbors, and more civic participation.

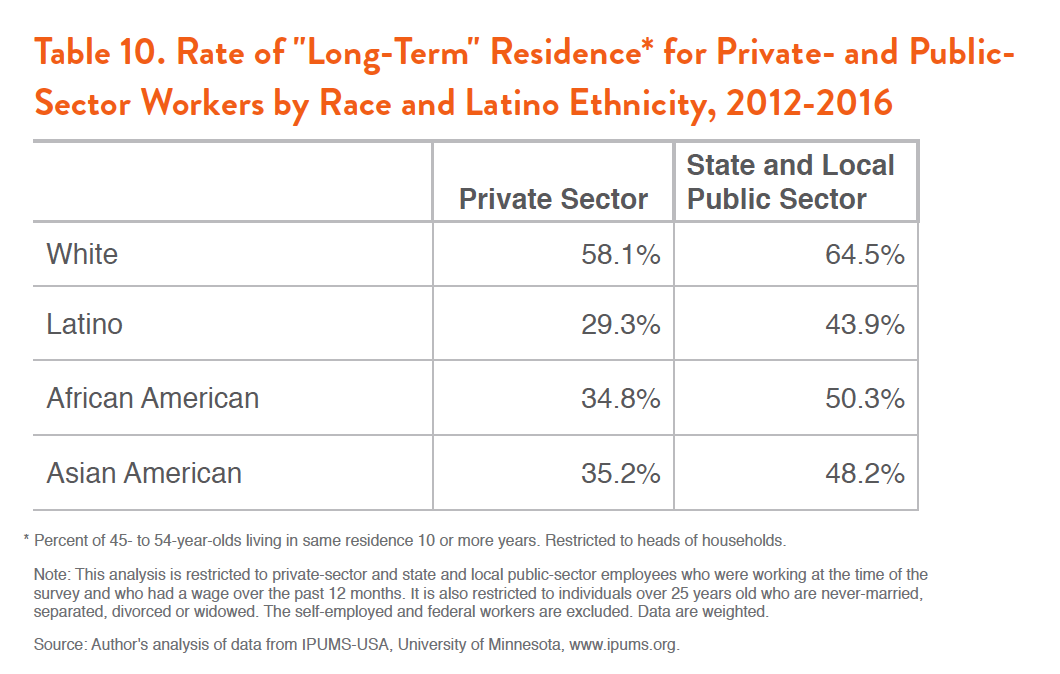

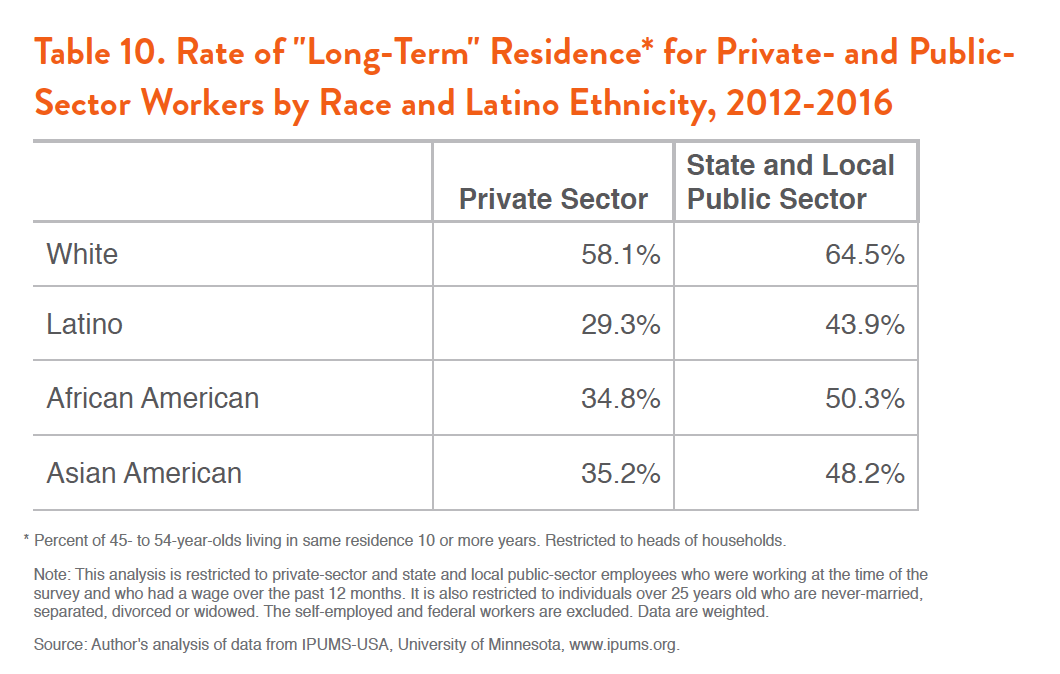

Table 10 shows the rates of 10 or more years, or “long-term,” continuous residence by racial and ethnic group. Public-sector workers are more likely to have lived in the same residence for 10 or more years.

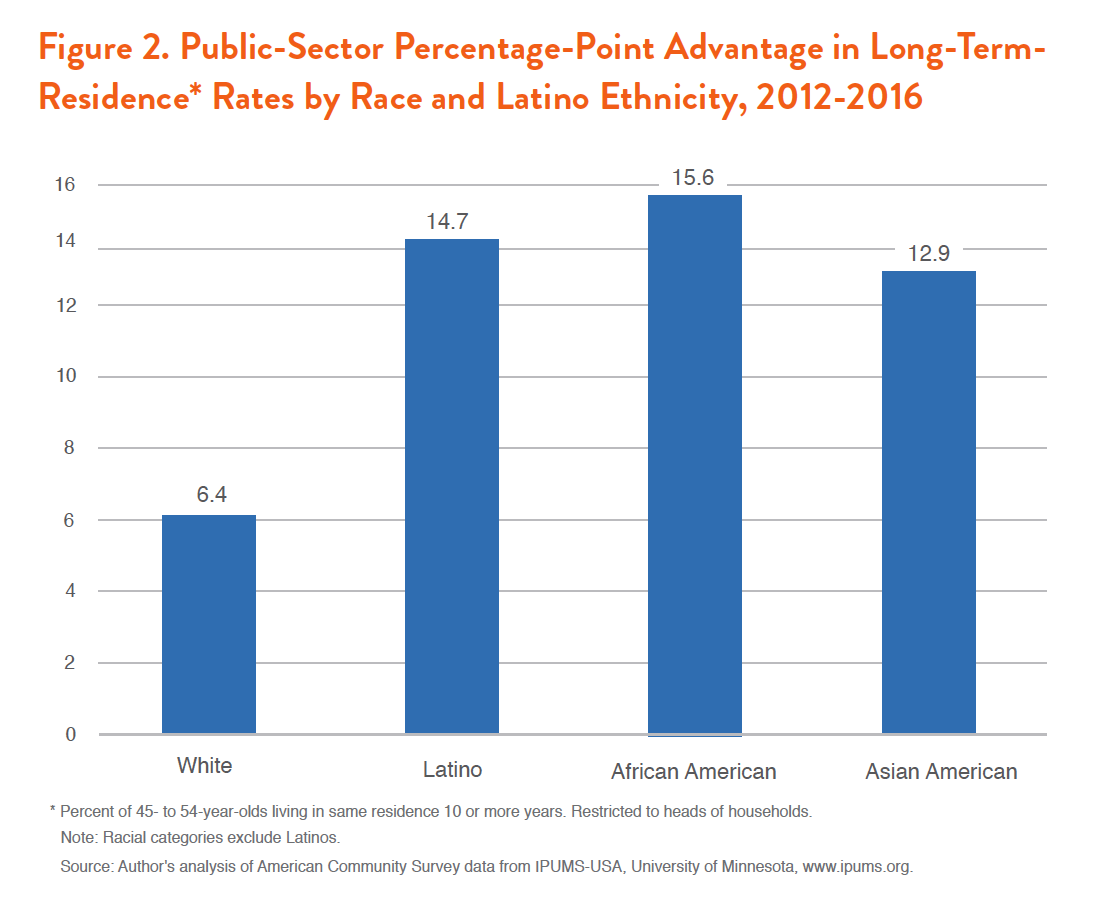

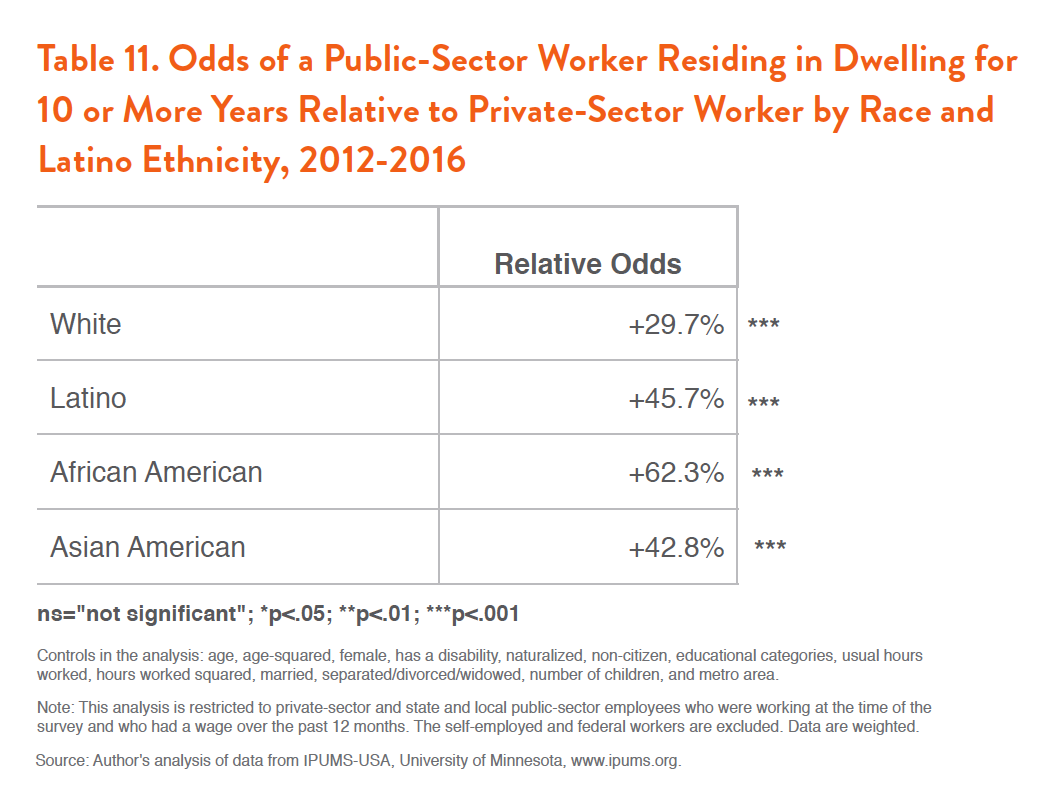

African-American public-sector workers have the biggest difference in continuity of residence. They are 15.6 percentage points more likely to have long-term residence in a community than African-American private-sector workers (see Figure 2). Latino public-sector workers have the second largest difference. They are 14.7 percentage points more likely to be long-term residents than Latino private-sector workers. Asian-American public-sector workers are 12.9 percentage points more likely than their peers in the private sector to be long-term residents. White public-sector workers are 6.4 percentage points more likely than white private-sector workers. The public-sector long-term-resident advantage is retained even after controlling for differences among private- and public-sector workers (Table 11). White public-sector workers are 29.7 percent more likely than similar white private-sector workers to reside long-term in a community. Latino public-sector workers see even greater odds. They are 45.7 percent more likely to reside long-term in a community than Latino private-sector workers. African-American public-sector workers have the greatest long-term odds. They are 62.3 percent more likely than their private-sector peers to reside long-term in a community. Asian-American public-sector workers have odds similar to that of Latino public-sector workers: They are 42.7 percent more likely than Asian-American private-sector workers to reside for 10 or more years in their community.

The public-sector long-term-resident advantage is retained even after controlling for differences among private- and public-sector workers (Table 11). White public-sector workers are 29.7 percent more likely than similar white private-sector workers to reside long-term in a community. Latino public-sector workers see even greater odds. They are 45.7 percent more likely to reside long-term in a community than Latino private-sector workers. African-American public-sector workers have the greatest long-term odds. They are 62.3 percent more likely than their private-sector peers to reside long-term in a community. Asian-American public-sector workers have odds similar to that of Latino public-sector workers: They are 42.7 percent more likely than Asian-American private-sector workers to reside for 10 or more years in their community.

The advantages of public-sector work are not limited to the individual or her family. They also benefit the communities in which public-sector workers live. We can see this benefit more directly by the fact that these workers are more likely to live long-term in their community, and thus help reduce crime, promote neighborhood cohesion, and increase civic participation.

Conclusion

Wage stagnation and increasing economic inequality are 2 of the major challenges of our time for Massachusetts and for the nation as a whole. Policymakers interested in addressing these problems need to preserve and grow public-sector employment. Public-sector jobs are more likely than private-sector jobs to provide the wages and benefits needed to sustain a family. Preserving and expanding them increases opportunities for families of all racial and ethnic backgrounds to move into or stay in the middle class in Massachusetts. Jobs in the public sector also help families build wealth and, with it, longer-term economic security. Workers in the public sector also help communities by fostering neighborhood stability, which reduces crime, builds neighborhood cohesion, and encourages civic engagement. Policymakers need to work to increase wages and benefits in private-sector jobs, so that economic opportunities grow for all workers. The labor policies in the public-sector jobs should serve as a guide for this policy development.

Public-sector jobs promote racial equality. In the public sector, Latino and African-American workers have a much better chance of escaping poverty than in the private sector. The loss of public-sector jobs undermines racial progress.

In an era of increasing economic polarization, public-sector jobs help to preserve and stabilize the middle class. These jobs provide good wages and benefits in a time when too many workers are seeing their wages and benefits stagnate and decline. As gentrification is pushing many families and especially families of color out of communities, public-sector jobs provide families with the economic resources and security that allows them to purchase a home, stay in their community, and strengthen their neighborhood.

Finally, it is important to note that the recent Janus v. AFSCME Council 31 Supreme Court decision was an attack on public-sector unions. An important reason why public-sector jobs are more likely to be good jobs is public-sector unions. There is a strong correlation between the decline of unionization and increasing economic inequality. The stronger unions are, the better wages are for average workers. Union jobs have also been shown to significantly increase the wealth of white and people-of-color workers. If Massachusetts policymakers want to preserve good jobs, they also need to protect and strengthen unions. Without unions, we will likely never be able to reverse the long-standing trend of stagnating and declining wages in Massachusetts.

The public-sector long-term-resident advantage is retained even after controlling for differences among private- and public-sector workers (Table 11). White public-sector workers are 29.7 percent more likely than similar white private-sector workers to reside long-term in a community. Latino public-sector workers see even greater odds. They are 45.7 percent more likely to reside long-term in a community than Latino private-sector workers. African-American public-sector workers have the greatest long-term odds. They are 62.3 percent more likely than their private-sector peers to reside long-term in a community. Asian-American public-sector workers have odds similar to that of Latino public-sector workers: They are 42.7 percent more likely than Asian-American private-sector workers to reside for 10 or more years in their community.

The public-sector long-term-resident advantage is retained even after controlling for differences among private- and public-sector workers (Table 11). White public-sector workers are 29.7 percent more likely than similar white private-sector workers to reside long-term in a community. Latino public-sector workers see even greater odds. They are 45.7 percent more likely to reside long-term in a community than Latino private-sector workers. African-American public-sector workers have the greatest long-term odds. They are 62.3 percent more likely than their private-sector peers to reside long-term in a community. Asian-American public-sector workers have odds similar to that of Latino public-sector workers: They are 42.7 percent more likely than Asian-American private-sector workers to reside for 10 or more years in their community.