- Nearly six million people are denied the right to vote due to felony offenses, even if they have completed their sentences.

- One out of every 13 eligible African Americans of voting age has lost their right to vote.

- States should not permanently take away the freedom to vote from any citizen. At a bare minimum, the right to vote should be automatically restored once a person is released from incarceration.

Prohibiting citizens from voting defies our democracy’s principle of one person, one vote. Yet across the country nearly six million citizens have been stripped of their right to vote due to prior convictions, even long after they have completed serving their sentences.1 The vast majority of these individuals, 75 percent, are no longer incarcerated and live in their communities without the ability to fully participate.2

Back to full report

The U.S. has the highest rate of incarceration in the world.3 Currently, over two million individuals are incarcerated—an increase of 500 percent over the past 30 years.4 Laws that permanently strip these individuals of the right to vote means that even more of our citizens will be denied the freedom to vote in the years to come.

Stripping formerly incarcerated individuals of the right to vote has a long and ugly racist history. Felony disenfranchisement laws have been used as a means to restrict political power. In the wake of the Civil War, felony disenfranchisement was enacted in part as a reaction to the elimination of the property test as a voting qualification. These laws served as an alternate way for wealthy elites to restrict the political power of those who might challenge their political dominance.5

Beyond disenfranchising poorer individuals, in the period following Reconstruction, several Southern states specifically tailored their disenfranchisement laws in order to bar Black male voters by targeting offenses believed to be committed most frequently by the Black population.6 For example, Alabama’s provision disenfranchised a man for beating his wife, but not for killing her because the author estimated, “the crime of wife beating alone would disqualify sixty percent of the Negroes.”7

Discriminatory police practices combined with rigid and racially biased drug laws have resulted in a disproportionate number of African Americans being arrested and convicted of felonies. As a result, one out of every 13 eligible African Americans of voting age is disenfranchised.8 In total, nearly eight percent of African Americans are disenfranchised because of such laws, more than four times more than the rate of non-African American disenfranchisement.9 In Florida, Kentucky and Virginia, more than 20 percent of African Americans of voting age are disenfranchised.10

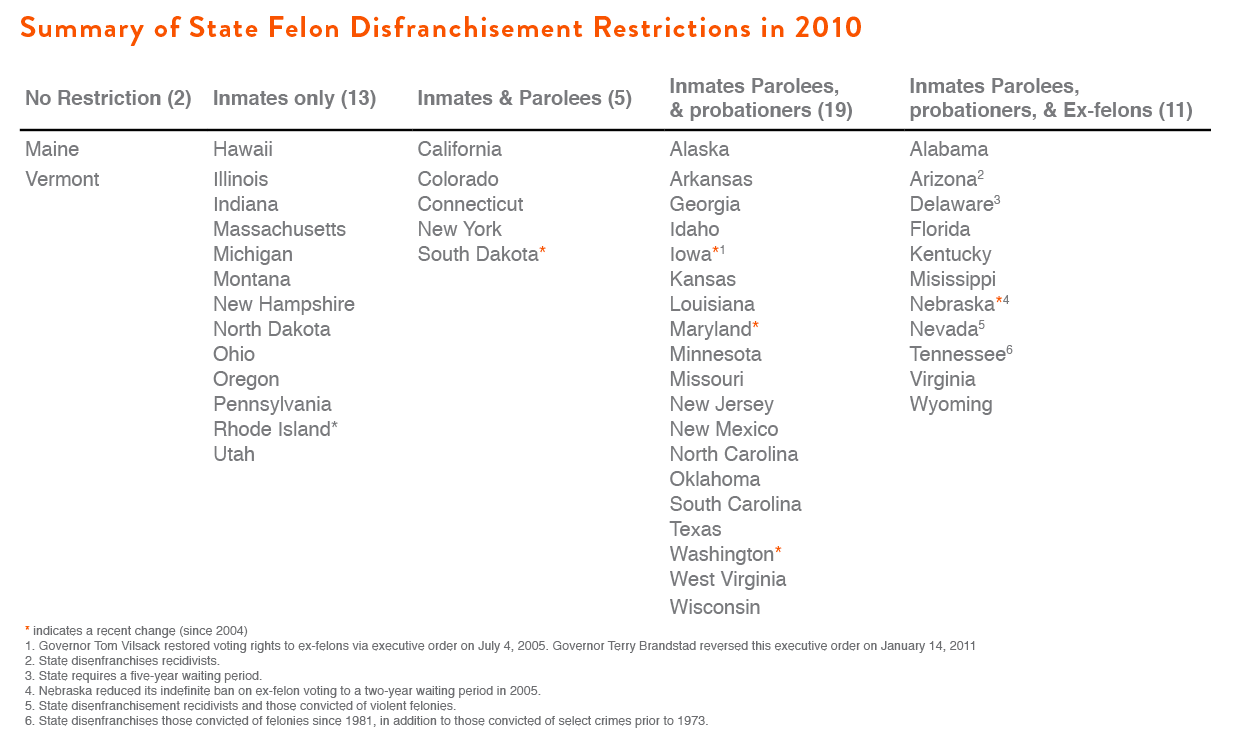

Almost every state in the U.S. takes away the right to vote from citizens convicted of felonies. Maine and Vermont are the only states that allow people currently incarcerated to vote.11 Once individuals have completed their sentences and are out of prison, however, most states continue to withhold the right to vote for ex-felons, as seen in the chart below. Thirty states do not allow persons on probation from felony convictions to vote and 35 states do not allow persons on parole to vote.12 Thirteen states continue to disenfranchise people even after they have successfully fulfilled their prison, parole, or probation sentences Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, and Wyoming.13

Restoring, or better yet never removing, the right to vote for formerly incarcerated individuals would result in millions of voters being brought back into the electoral system, further strengthening our democracy, and helping to restore political representation to disenfranchised communities.The number of disenfranchised voters runs into the millions, in an era when electoral outcomes can be affected by tiny margins. For example, in 2000, the Presidential election was decided by only 537 votes in Florida, a state that, at the time, had one of the most restrictive disenfranchisement laws.14 As a result, an estimated 600,000 individuals who had fully completed their sentences were ineligible to vote, nearly 1,000 times the winning margin.15 There is no way to know how many of the 600,000 would have voted and who they would have voted for, but it is clear that it could have had a significant impact on the national election.

Policy Recommendations

- The freedom to vote should not be taken away as a result of a felony conviction.

- Alternatively, to set a floor for the remaining 48 states that do strip voting rights, Congress should pass the Democracy Restoration Act, (DRA) introduced first in 2008 by former Senator Russ Feingold and Rep. John Conyers. The DRA would set a uniform federal policy that would automatically restore the rights of an individual previously convicted of a felony to vote in federal elections, unless the individual is still serving his or her sentence at the time of the federal election.16

- On the state level, similar policies should be adopted that would at a minimum automatically restore the right to vote for anyone convicted of a felony once released from incarceration. Currently, 13 states plus the District of Columbia automatically restore voting rights upon release from prison.17

Prison-based Gerrymandering

A long-standing flaw in the decennial census results in prison-based gerrymandering, where roughly 2 million incarcerated people are counted in the wrong place for purposes of redistricting.18 Although people who are incarcerated generally cannot vote, and remain legal residents of their home communities under the laws of most states, the Census Bureau currently counts incarcerated people as residents of the prison where they are incarcerated, not where their homes may be.19

Prison-based gerrymandering gives people who live near large prisons extra influence at the expense of voters everywhere else, undermining the one person, one vote principle of the 14th Amendment. It also creates incentives for elected officials to increase the incarcerated population.

For example, upstate New York has been steadily losing population.20 In the 2000 Census, almost one-third of the persons credited as having “moved” into upstate New York during the previous decade were people sentenced to be incarcerated in upstate prisons. While counted for redistricting purposes, these “new residents” cannot vote and cannot interact in other meaningful ways with the cities and towns where they are incarcerated – they cannot shop, eat at restaurants, buy or rent homes, use public transportation, or engage in any of the normal activities of an actual resident of the prison town. But as long as incarcerated persons are counted for redistricting purposes, it creates an incentive for elected officials to increase the incarcerated population in order to keep their seats or offices, rather than risk losing a seat due to a population decrease.

Fortunately, states and localities are working to end prison based gerrymandering. New York, Maryland, Delaware and California have passed legislation to use state correctional data to ensure districts are drawn on data that counts incarcerated people at home.21 New York and Maryland have successfully defended their plans in court and implemented this reform in drawing their districts following the 2010 Census; California and Delaware will implement their reforms for the redistricting following the 2020 Census.

The legislative or executive branches in several states (Virginia, Colorado, New Jersey, Mississippi) require or encourage local governments to modify the census and refuse to use prison populations as padding. More than 200 rural counties and municipalities around the country make these adjustments on their own.

On the federal level, the Census Bureau changed its 2010 data publication schedule to make it easier for states and localities to identify prison populations in the Census redistricting data.22 However, states must rely on their own data to assign prisoners to their proper home districts, and the new release was not early enough for every state to benefit. Moving forward, the Census Bureau should change its “usual residence” rule to count incarcerated persons as residents of the community where they resided prior to incarceration.23

Back to full report

Endnotes

- Jean Chung, Felony Disenfranchisement: a Primer, (June 2013), available at http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/fd_Felony%20Disenfranchisement%20Primer.pdf. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Max Raskin and Ilan Kolet, United States Jails More People Than Any Other Country: Chart of the Day, (Oct. 15, 2012), available at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-10-15/u-s-jails-more-people-than-any-other-country-chart-of-the-day.html. ↩

- The Sentencing Project, Incarceration, (Nov. 26, 2013), available at http://www.sentencingproject.org/template/page.cfm?id=107. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Chung, Felony Disenfranchisement: a Primer. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Christopher Uggen, Sarah Shannon and Jeff Manza, State-Level Estimates of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, (July 2012), available at http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/fd_State_Level_Estimates_of_Felon_Disen_2010.pdf. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Marc Mauer, Voting Behind Bars: An Argument for Voting by Prisoners, (2011), available at http://sentencingproject.org/doc/Howard%20Law%20%20Voting%20Behind%20Bars.pdf. ↩

- Ryan S. King, Felony Disenfranchisement Policy in the United States, (Oct. 2006), available at http://www.sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/fd_decade_reform.pdf. ↩

- Brennan Center for Justice, Democracy Restoration Act, (Dec. 20, 2011), available at http://www.brennancenter.org/legislation/democracy-restoration-act. ↩

- Nonprofit VOTE , Voting as an Ex-Offender, (2013), available at http://www.nonprofitvote.org/voting-as-an-ex-offender.html. ↩

- Ben Peck, Testimony: The Census Count and Prisoners: The Problems, The Solutions and What the Census Can Do, (Oct. 22, 2012), available at http://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/BenPeck_Testimony_PrisonBasedGerrymandering101212.pdf. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Demos, What the Census Can Do, (Oct. 14, 2010), available at http://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/FACTSHEET_PBG_WhatCensusCanDo_Demos.pdf. ↩

Back to full report