Introduction

Everyone, regardless of how much money they have in their bank account, deserves to have a voice in our democracy and a say in how their city is run. Too often, however, the strength of a person’s voice in our society is determined not by the power of their ideas but by the size of their wallet. Bolstered by a series of Supreme Court decisions allowing practically unlimited spending in political campaigns, our current election financing system gives wealthy, overwhelmingly white donors outsized power to influence policymakers and our democracy, at the expense of the voices and needs of everyday people, especially communities of color.

Despite Baltimore’s racial and economic diversity, a disproportionately wealthy, white, and male donor class fuels some of the city’s most important races. Donors to the 2016 mayoral and city council elections were 64 percent white and 59 percent male, and nearly a half of donor households—48 percent—made over $100,000 per year. The city of Baltimore is 30 percent white, 47 percent male, and only 20 percent of the population makes $100,000 or more. It’s no surprise, then, that everyday Baltimoreans can feel like the city is not responding to the issues in their lives.

The soaring costs of running electoral campaigns—in Baltimore and across the country—lead candidates and elected officials to spend significant time talking to wealthy supporters and potential high-dollar donors, and relatively little time talking to the rest of us. As a result, public policy throughout the United States is dictated by a small group of economic elites rather than the vast majority of Americans who come from middle- and working-class communities. Political science research finds that members of Congress pay disproportionate attention to economic issues of concern to the wealthy elite, and when the preferences of this economic minority are different from the needs of a majority of everyday Americans, elected officials prioritize the wishes of their wealthy donors and pro-business interest groups.

Big money in politics affects how lawmakers decide to govern, but it also fundamentally changes who can run for office in the first place, keeping many qualified candidates—especially candidates of color, women, and people from working-class backgrounds—off the ballot and out of office. These leaders bring important perspectives and bold new policy ideas to improve people’s lives, but they lack the deep-pocketed networks that are too often the ticket into the race. An analysis of federal, state, and county candidate and elected official data by the Reflective Democracy Campaign found that, even though women make up 51 percent of the population, they were only 28 percent of candidates in 2016; people of color are 39 percent of the population but were a mere 12 percent of candidates.

Fortunately, the people of Baltimore have rejected this distortion of democracy and overwhelmingly support an entirely new way of funding elections. Through Baltimore’s new small-donor public financing program—approved by 75 percent of Baltimore voters in November, 2018—qualifying candidates for mayor, city council, and comptroller will be able to access public matching funds for their campaigns, in exchange for agreeing to limits on who they accept donations from and caps on the size of contributions from these donors. The Baltimore Fair Elections Fund holds the potential to put the demos—the people—back into Baltimore’s democracy, and to reverse the dynamic in which wealthy donors’ voices count more than everyday people’s. Evidence from other cities and states suggests that, if implemented well, Baltimore’s small-donor public financing program will make it possible for a more diverse set of candidates to run for office and, in turn, prompt the adoption of policies that are more aligned with the public’s preferences.

Small-donor public financing cannot come too soon to Baltimore. Using data on contributions from individual donors to 2016 general election candidates for mayor and city council, this brief examines the demographics of Baltimore’s donor class and makes the case for a robust, equitable small-donor public financing program as an antidote to the crisis of big money in politics in the Charm City. We find that:

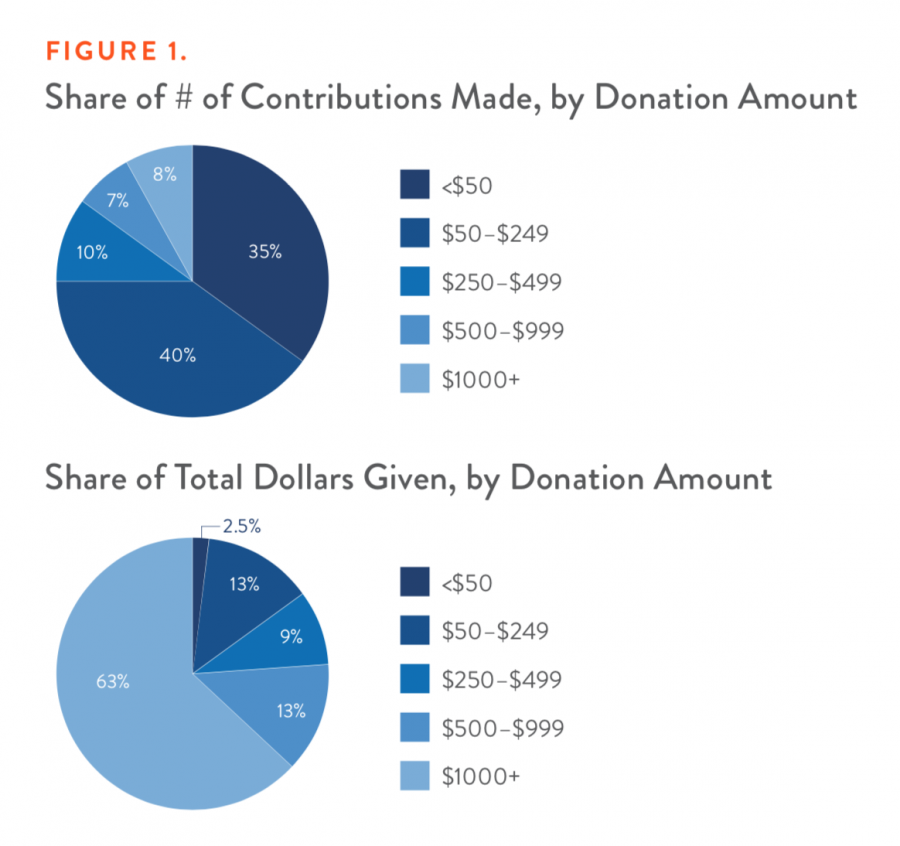

- Large donations play an outsized role in contributions to Baltimore candidates. Seventy-six percent of the total funds raised by candidates from individuals came from large contributions ($500 or more), despite the fact that these large gifts were only 15 percent of total individual contributions. In contrast, 35 percent of individual contributions to these candidates were of amounts of less than $50, but these small gifts comprised only 2.5 percent of total funds raised.

- The donor class is not representative of the racial, gender, income, or age diversity of Baltimore City.

- Black people make up nearly two-thirds of Baltimore residents but only one-third of donors; white people make up less than a third of the city but constitute two-thirds of donors. Latinx, Native American, Asian American, and other communities of color together make up almost 10 percent of Baltimore’s population but are virtually unrepresented in the donor pool.

- Women make up more than half of Baltimoreans but well under half—44 percent—of donors, and they give on average $250 less per donation than men.

- The donor class is much richer than Baltimore overall. Half of all families in Baltimore make $47,000 or more per year, yet half of donor households make more than $100,000 per year.

- Donors in Baltimore are much older than the city overall. Baltimoreans under 25 make up nearly a third of the population but only 1 percent of the donor class.

- Donations from outside Baltimore play a significant role in the city’s elections. Only a little over half—57 percent—of all individual donations to general election candidates are from residents of Baltimore; the remaining 43 percent are from people outside the city. These outside contributions are 50 percent larger, on average, than donations from Baltimoreans. Out-of-state dollars also play a role. Thirteen percent of contributions are from individuals living outside Maryland, including tens of thousands of dollars from D.C., Virginia, California, and New York, among other states.

- In contrast, those who donate in small amounts are more reflective of Baltimore’s diverse residents. Women, communities of color, and low-income people are better represented among those giving less than $50 than any other donor group, and their presence in the donor class overall plummets as donation size rises.

- Because the small-donor pool is more representative of Baltimore’s population, small-donor public financing can increase the voice and power of everyday residents, moving Baltimore closer to representative democracy and political equality.

- The Fair Elections Fund should be designed with community input, and it should include program elements that ensure participation is viable for candidates from all districts, and that promote engagement by all Baltimoreans.

About the Data

This analysis is based on data on contributions from individuals to mayoral, city county president, and city council district general election candidates between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2016, publicly available via the Maryland Campaign Reporting Information System (MCRIS). Demographic data is derived from modeling methodology developed in conjunction with political scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The data analyzed in this brief do not include donations to candidates for these races who did not continue after the primary, nor do they include contributions from any non-individual entity. Because our analysis focuses solely on individual contributions directly to campaigns, it does not cover the full range of funds potentially available to candidates (i.e. those from parties, PACs, interest groups, or direct expenditures on behalf of candidates). Therefore, the totals described here do not represent the total campaign resources at candidates’ disposal, an important fact to keep in mind when reviewing the data presented here. The contributions covered in this analysis do include contributions of cash/check/credit/direct transfers, in-kind contributions, non-candidate loans, raffles, and tickets from individuals. Although loans must be repaid, they are included in contributions because they are of great value to candidates. The total number of loans is very small, but the size of the loans is very large relative to other types of contributions. All of the loans from individuals we identified were to successful mayoral candidate Catherine Pugh.

Big Money Dominates Baltimore Elections

Big money in politics is a big problem in Baltimore City. During the 2016 mayoral and council elections, very large donations—those of $1,000 or more—accounted for just 8 percent of donations but constituted 63 percent of total funds raised from individuals for these races. Similarly, 7 percent of contributions were of amounts between $500-$999, but these large gifts accounted for 13 percent of total funds raised. Together, these large donations, which totaled just 15 percent of contributions, made up 76 percent of total dollars raised from individuals in the 2016 mayoral and council races. In contrast, the 35 percent of all individual donations that were for less than $50 comprised only 2.5 percent of total funds raised.

The problem is getting worse. In the 2007 and 2011 elections, the average donation to the winning mayoral candidate were $525 and $681, respectively. During the last mayoral race in 2016, that average donation soared to $1,119, more than twice its size less than a decade before (and well over an increase that would be expected due to inflation). In 2007, Democratic mayoral candidates collectively spent less than $3 million, and in 2011 the 4 leading candidates spent about $3.3 million; In 2016, the top 4 spenders among mayoral candidates collectively spent $7.6 million. Average spending across all mayoral candidates increased from $591,000 in 2011 to $813,000 in 2016. The winning candidate, Catherine Pugh, spent nearly $3 million to win her race in 2016, three-quarters of a million dollars more than Stephanie Rawlings Blake spent to win in 2011 and Sheila Dixon spent in 2007.

Council elections are also getting more expensive. Successful candidates for city council district races raised an average of $140,000 per race in 2016, up from an average of $94,000 raised in 2011. These averages mask considerable variation in totals raised across council districts, which are impacted by the competitiveness of a race as well as relative wealth across districts. Variation notwithstanding, across 12 of 14 council districts, candidates raised more—in some cases significantly more—in 2016 than they did in 2011. Winning council president candidate Bernard “Jack” Young raised $543,000 in 2011, a sum that jumped to $878,000 in 2016.

As important as the ever-growing role of money in Baltimore’s elections, and as the outsized role of large gifts, is the makeup of the donor class itself. In order to better understand who funds Baltimore’s elections and, in turn, who holds significant influence in the city’s policy decisions, Demos explored the demographics of individual donors to Baltimore’s mayoral and council elections during the 2016 election cycle. The findings are sobering: a donor class completely out of sync with the diversity of the City of Baltimore.

Baltimore’s Donor Class Does Not Reflect the City’s Diverse Residents

Race

The donor class in Baltimore is much whiter than the city. While 30 percent of Baltimore residents are white and 63 percent are black, the donor pool in Baltimore is the opposite—64 percent white and 32 percent black. Latinx Baltimoreans make up 5 percent of the population but less than 1 percent of the donor class. Native American, Asian American, and other Baltimoreans of color make up another 5 percent of the city but are virtually absent from the donor pool.

Unsurprisingly, when considering total dollars given by individuals, the picture is just as bleak. The nearly two-thirds of black Baltimoreans who make up the city account for just a quarter of all individual dollars—averaging $363 per gift—to mayoral and council candidates. The white Baltimoreans who represent just under a third of the city account for nearly three-quarters of total individual dollars given. Latinx donors account for a tiny fraction of total dollars and give far less—$261 per gift, on average—than white donors. Contributing an average of $510 per donation, white donors give nearly $150 more per donation on average than African-American donors and twice as much as Latinx donors. The median contribution of white donors is $100, twice that for black and Latinx donors.

Gender

Women make up a slightly larger share of the Baltimore City population than men—53 percent of Baltimoreans are female and 47 percent are male. Yet, when it comes to the people funding Baltimore’s mayoral and council elections, the pool is overwhelmingly male. Sixty-one percent of donors to mayoral general election candidates are men and only 39 percent are women; donors to council president candidates are similarly disproportionately male. The donor pool among district council members is somewhat more balanced between men and women, though men are still overrepresented—and women underrepresented—among their donors.

Overall, men donated 2.5 times as much money to mayoral and council candidates as women. Their average contributions were close to twice as large—and their median donation a third larger—than those of women.

Income

The donor class is much richer than Baltimore overall. The typical family in Baltimore makes just under $47,000 per year, yet only around one-quarter of donors make that amount or less. The typical donor household makes at least $100,000 annually.

These wealthy donors have an outsized voice in Baltimore’s mayoral and council elections. While the very wealthy account for one-fifth—20 percent—of households, they make up nearly half—48 percent—of donors to 2016 mayoral and council candidates.

Age

The donor class is also deeply distorted when it comes to age. Baltimoreans under the age of 25 make up just over 30 percent of the population but only 1 percent of donors. Meanwhile, Baltimoreans 50 years or older are also roughly 30 percent of the population but make up a full 60 percent of the donor class. While many young people will not have much disposable income—the typical Baltimorean under 25 makes between $25,000-$30,000 per year—their lives are also governed by local politics, and they deserve a voice in Baltimore’s policymaking decisions. Given their virtual absence from the donor pool, under the current campaign financing system in Baltimore these young people are unlikely to have any sway whatsoever with their elected officials.

Outside Contributions

Donations from outside Baltimore play a significant role in the city’s elections. Only a little over half—57 percent—of all individual donations to general election candidates for mayoral and council races are from residents of Baltimore; the remaining 43 percent are from people outside the city. Contributions by non-Baltimore donors averaged $305 per gift, 50 percent larger than those from Baltimore donors, which were $200 on average. The size differential between local and out-of-Baltimore donations varied significantly among candidates, with mayoral candidates averaging roughly $200 more per gift from donors outside Baltimore, council president candidates about $125 more per outside gift, and district council candidates overall about $80 more per outside gift.

A sizeable portion of individual contributions to mayoral and council races in 2016 came from outside Maryland. Thirteen percent of all individual donations to these races, or about $415,000, were from non-Maryland residents, with a few states generating significant contributions. Out-of-state donors gave about $65,000 from the District of Columbia, $56,000 from New Jersey, $48,000 from Florida, $40,000 from California, $36,000 from New York, $26,000 from Pennsylvania, $25,000 from Illinois, $24,000 from Virginia, and $95,000 from all other states together.

The Small-Donor Pool Looks More Like Baltimore

While the donor class overall is less representative of Baltimore city’s population, when we drill down by donation size, it becomes clear that the small-donor pool in mayoral and council elections does a better job of approximating—and in some cases closely reflects—the demographics of the city overall. Women, for example, make up 53 percent of the overall population and 52 percent of small donors (those giving less than $50). As donation size rises, however, the presence of women drops; they make up just 28 percent of those contributing $500 or more.

Small donors also more closely approximate Baltimore’s racial diversity than large donors, though the small-donor pool is still disproportionately white. Thirty-seven percent of small donors to mayoral and council races are black, while only 21 percent of large donors are. Meanwhile, 57 percent of small donors are white, while white donors make up a full 75 percent of those giving $1,000 or more.

Donors are also disproportionately high-income. While only a fifth of Baltimoreans make $100,000 or more per year, nearly half of large donors do. It is intuitive, of course, that wealthy people can afford to donate more, while lower-income people have much less disposable income for things like campaign contributions. It is still highly problematic, however, for the goal of representative democracy, since there is growing evidence that, “when a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites or with organized interests, they generally lose.”

In general, the small-donor pool, while not perfectly reflective of Baltimore’s class diversity, better approximates the city’s income than the rest of donors. Fifty-five percent of Baltimoreans overall, and 47 percent of the small-donor class, make less than $50,000. Only 14 percent of large donors (those giving $1,000 or more) have incomes at that level.

Race and wealth are, of course, inextricably connected in our society. The racial and income disparities between small and large donors and the general population in Baltimore are perhaps best understood in terms of the racial wealth gap—the absolute differences in wealth between white households and households of color. The consequence of centuries of economic exclusion—from slavery to segregation, redlining, and predatory lending—the racial wealth gap in the United States is as significant as it is persistent. Data from the Survey of Consumer Finances show that, in 2013, the median white household held $13 in net wealth for every dollar held by the median black household, and $10 in net wealth for every dollar of the median Latinx household. It is no surprise, then, that the large donor pool is characterized by more white people and by people with higher incomes than the small-donor pool, or that both are wealthier and whiter than the population overall.

The perpetual presence of these disparities is not a foregone conclusion, however. Just as public policies created and fuel the racial wealth gap, so too can policies designed with racial equity at the forefront chip away at these inequalities. A closer look at the demographics of the small-donor pool makes clear this subset of the donor class better reflects the demographics and, in turn, the interests of the city overall. A campaign financing system that prioritizes the voices of these everyday people and allows for all Baltimoreans, irrespective of race, class, gender, or age, to participate fully in elections could move Baltimore closer to the goal of political and economic equality.

Businesses, Developers, and Other Non-Individual Donors Make Up More Than Half of All Campaign Spending in Baltimore

While this brief explores the nature of contributions from individuals and the demographics of that donor class overall, contributions from individuals are but one source of campaign funds in Baltimore’s municipal elections. In fact, contributions from individuals constitute less than half—46 percent—of all funds raised by general election candidates in 2016; a whopping 53 percent came from businesses, political parties, PACs, unions, and other entities that are not people but do have deep interest in elections (the remaining 1 percent was self-financing from candidates or their spouses). At roughly $1,200 per average donation, these non-individual contributions are 3 times as large, on average, as contributions from people, which average $400.

As Figure 16 breaks out, the vast majority of these non-individual dollars—85 percent—are from entities labeled in the campaign finance data as “businesses, groups, and organizations,” entities which in Baltimore include developers, investment firms, banks, law and lobbying firms, and other interest groups. While they often get as much attention and criticism, contributions from labor unions and political committees—8 and 7 percent, respectively—play a much smaller role. The Baltimore Sun calls these contributions from developers and other entities that do business with government “the bread and butter of campaign donations” in local government, and rightly identifies campaign finance, as a result, as “an area rife with potential conflicts of interest.” As long as campaigns are fueled so significantly by developers and other entities that are not people—and whose interests too often do not align with those of actual people—politics and public policy will also fail to serve the residents of Baltimore as they should.

A Robust Fair Elections Fund Would Help Get Money Out of and People Into Baltimore’s Elections

Fortunately, the people of Baltimore recognized the problem of big money in their elections and utilized their direct democracy powers to change who has access and voice in Baltimore’s democracy. On November 6th, 2018, Baltimoreans overwhelmingly supported the creation of a small-donor public financing program. National polling shows that 85 percent of Americans believe we must “fundamentally change” or “completely rebuild” the way political campaigns are funded in the United States– 75 percent of Baltimoreans agreed when they voted for the Baltimore Fair Elections Fund.

While the precise details of a public financing program in Baltimore are still being worked out, the Baltimore Fair Elections Fund would ensure candidates without wealthy networks or corporate benefactors could run for and win elected office. Under the program, matching funds would be available to qualifying candidates who reject contributions from corporations, unions, and other non-individuals, and agree to accept only individual contributions up to a certain limit. Matching funds would be tiered, with more matching dollars awarded for the smallest donations. As such, public financing in Baltimore would ensure candidates could run successful campaigns by spending more time talking to their constituents, and it would especially encourage candidates to engage with low-dollar donors, as well as people who have not donated in the past. Current campaign financing rules marginalize the perspectives of these small-dollar and potential new donors. The Baltimore Fair Elections Fund would rectify this distortion of democracy by amplifying the voices and the power of small-dollar donors. In so doing, the program would help bring people to the forefront of politics and public policy in Baltimore, and reduce the outsized power of big money in Baltimore’s elections.

The matching funds model is especially important in Baltimore, where dramatic differences in wealth across the city—and between races—mean candidates for city council districts have very different fundraising prospects. Figure 20 maps median household income by census block and council district. The significant variation in income and wealth across council districts is concerning for many reasons, and highly relevant for designing a robust, sustainable Fair Elections Fund for Baltimore.

In 2016, the average donation from Baltimore donors to winning council candidates ranged from $69 to $482. This variation is related to the competitiveness of a race but is also impacted by extreme wealth disparities across districts. A robust, progressive matching funds structure would help counter these wealth inequities and make winning elected office a possibility for Baltimoreans from diverse economic backgrounds and for other groups who often have limited access to wealthy networks, including more women and people of color. Additional policy options, described below, would make the Fair Elections Fund even more substantive and equitable.

Options for Inclusive and Equitable Program Design

Additional program elements, beyond the tiered matching system currently under consideration, could make Baltimore’s elections among the most inclusive and equitable in the country. Specifically, in designing the Fair Elections Fund, policymakers in Baltimore should:

- Design the program with input from community members and community-based organizations, who will be instrumental in successfully implementing the program, and create mechanisms for ongoing review, analysis, community input and modification over time.

- Make participation in the program accessible for all candidates through program adjustments like lowering qualifying thresholds and/or incorporating seed grants like those pioneered in Washington, D.C., which make public funds available to qualifying candidates at critical early stages of the campaign cycle.

- Amplify the voices of everyday people, especially those who are unable to make even a small campaign contribution, by incorporating generous match rates and/or including something like the “democracy dollars” voucher system pioneered in Seattle, WA and proposed in Albuquerque, NM and Austin, TX.

- Ensure the program remains viable for all types of candidates and at every stage of election cycle by connecting caps on the amount of matching funds candidates can receive to changing spending data, and by evaluating and, as necessary, adjusting qualifying requirements, match ratios, and match caps after each election cycle.

Small-Donor Public Financing Is Working Across the Country

The dozens of states and localities across the country that have some form of public financing—some decades old and others brand new—provide compelling signs of small-donor public financing’s efficacy in getting big money out of and people into our elections. Evidence from these programs suggests that, after their implementation, small-donor public financing systems lead to the adoption of policies that are more aligned with the public’s preferences, and that more people—in particular a more diverse set of candidates—are able to run for office, among other benefits.

In Connecticut, for example, a grants-based public financing system helped facilitate passage of a policy with overwhelming support among people of all races and political persuasions—paid sick leave. Despite significant public popularity, a proposal for paid sick leave had stalled in the legislature, after the Connecticut Business & Industry Association and other major contributors to elected officials then leading the state mounted fierce opposition. After public financing passed in 2005, candidates for governor and general assembly supportive of paid sick leave successfully campaigned with public funding, defeating multi-millionaire opponents and ultimately passing paid sick leave for Connecticut.

New York City’s public financing program, which employs a matching model similar to that proposed in Baltimore, has been particularly successful; in 2017, the mayor and 7 of 10 winning city council candidates participated in the program. The city’s matching funds model has contributed to a city council made up of people from a wide array of professional experiences, from lawyers to police officers, teachers and community organizers, and it helped the first woman of color ever elected to a citywide position in New York City, former Public Advocate Letitia “Tish” James, to win her race. James describes the challenges facing her as a candidate without independent wealth or rich connections and the impact she has had in her role as Public Advocate:

“I don’t come from big money. I don’t know a lot of people with deep pockets. Most of the donors who gave to me are mothers, residents from public housing, individuals who remain at home… we were successful in passing paid sick leave, paid family leave, more affordable housing, lawyers for individuals who are being evicted, and… a retirement security under my leadership, to make sure that individuals retire in dignity. That’s what we have done with a reflective and a representative government.”

Beyond the important work she led on behalf of New York City’s residents, James’ experience as Public Advocate undoubtedly laid the groundwork for her recent election as Attorney General of New York State. James is the first woman and the first black person to serve as Attorney General in the state’s history, and she is the first black woman ever elected to statewide office. James’ story demonstrates the important role public financing can play in developing the leadership of local candidates, who may in turn run for and win statewide or national elected office.

The City of Seattle is pioneering a new form of public financing—vouchers—and early evidence suggests the program is successful in diversifying the donor pool and encouraging candidates to rely less on big money and more on small donors. After a strong majority of voters supported the Honest Elections Seattle ballot initiative in 2015, the city now sends all residents four $25 Democracy Vouchers that can be donated to participating candidates in city elections. An Every Voice analysis of the Democracy Vouchers in its first election cycle, 2017, found that a historic number of Seattle residents participated as campaign donors. At approximately 25,000 people, Seattle’s donor class more than tripled from the 8,200 who gave in 2013, and 84 percent of those donors were new in 2017, including more people of color, women, young people, and lower-income residents than ever before. Candidates in every eligible race relied less on big money, with 87 percent of funds coming from small contributions of $250 or less and Democracy Vouchers, compared to just 48 percent of funds in the same races in the 2013 elections.

Washington, D.C. is also pioneering an adapted form of small-donor public financing. The new program, signed into law in 2018, employs a matching funds model like that of New York City, but also provides seed-money grants to qualifying candidates early in their races. As in Baltimore, there is a significant wealth differential across wards in the District, a wealth gap that, as in most places, is highly racialized. This reality makes fundraising more difficult for candidates in some council races, particularly candidates from wards with more sizeable communities of color and especially during the critical early months, before campaigns gain steam. The hybrid seed-grant model developed in D.C. advances racial equity across the District and allows participating candidates to run viable campaigns at every stage of the election cycle.

Conclusion

Big money in elections is among the greatest threats to a healthy, inclusive democracy. In Baltimore, campaign funds are dominated by developers, businesses, PACs, and other special interests, and donations from individuals are given by a donor class that is disproportionately white, male, wealthy, and older than the city’s residents overall. As a result, public policy in the city too often does not align with the interests and priorities of Baltimoreans. Fortunately, an alternative exists in small-donor public financing models, which have been successful at democratizing campaign finance and, in turn, governance and policy in cities and states across the country. Baltimoreans are already on their way to investing in a healthy, inclusive, reflective democracy by voting to create a robust small-donor public financing program, the Baltimore Fair Elections Fund. If designed with racial equity, as well as program viability and sustainability, in mind, Baltimoreans from all walks of life will soon have an equal chance to participate in the robust, vibrant democracy that results.

Acknowledgments

This report was produced in collaboration with Jesse Rhodes, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.