Student debt has skyrocketed over the past decade, quadrupling from just $240 billion in 2003 to more than $1 trillion today. If current borrowing patterns continue, student debt levels will reach $2 trillion in 2025. Average debt levels have risen rapidly as well: two-thirds (66 percent) of college seniors now graduate with an average of $26,600 in student loans, up from 41 percent in 1989. These trends are all part of the rise of the “debt-for-diploma” system.

How Did We Get Here? State Disinvestment

Until about the mid-1990s, state universities and colleges were affordable for middle-income households. Lower-income students could pay the bill with grants and part-time jobs. Debt was the exception, not the rule.

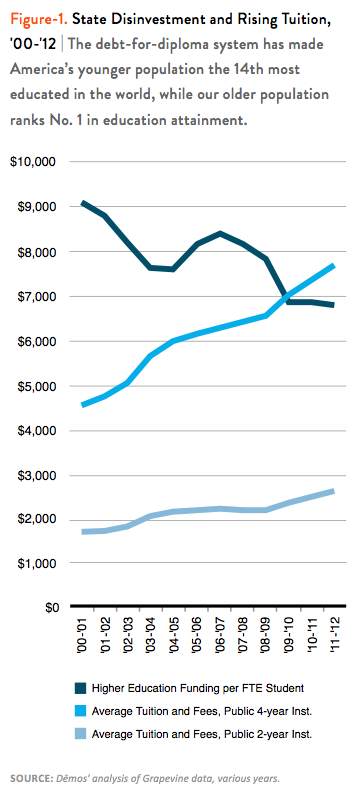

This current debt-for-diploma system is the result of overlapping trends, including the steady decline in public investment in state colleges and universities, down 25 percent per full-time equivalent student since 2000. State policy decisions are largely responsible for this major cost shift onto students and families (Figure 1).

Long-Term? Lifetime Wealth Loss

In order to explore the impact of tying opportunity to debt, Demos quantified just how much soaring debt levels impact college-educated households’ financial stability over a lifetime.

In the Demos report At What Cost?, we compared the projected debts and assets of a college-educated household with average levels of education debt to a similar household without debt. Here are some of the findings:

- 17.5% of wealth over a lifetime is lost to student debt.

- Student debt causes a wealth loss of 4 times the debt amount.

- Nearly two-thirds of this loss ($134,000) comes from the lower retirement savings of the indebted household, while more than one-third ($70,000) comes from lower home equity.

- We can generalize this result to predict that the $1 trillion in outstanding student loan debt will lead to total lifetime wealth loss of $4 trillion for indebted households.

What Can We Do? Contract For College: Policy Recommendations

The Contract for College would unify existing strands of federal financial aid— grants, loans and work-study—into a coherent, guaranteed financial aid package for students. Grants would make up the bulk of aid for students from low- and moderate-income families. The Contract is designed to reorient federal aid back to a more grant-based system and ensure that students from all financial backgrounds have upfront knowledge and understanding of the amount and type of financial aid that will be available during their entire course of study. The Contract also provides direct federal investment in community colleges to fund the President’s American Graduation Initiative.

These recommendations reinvent the federal financial aid system to double the percentage of college qualified students from low and moderate-income families who enroll and complete college degrees.

While each student’s final Contract will be based on the institution costs where the student chooses to enroll, we can use the average cost of attendance for public 4-year colleges to model the type of aid students at different income levels will receive under the Contract. Figure 3 is for illustrative purposes and includes costs for tuition, room and board, books and transportation.

Conclusion

As debt financing has become the required gateway for attending a 4-year university, we’re experiencing growing gaps by race and class in who enrolls and completes 4-year degrees.

The debt-for-diploma system has distorted the way we think about the returns to a college education. Vanishing from our discourse is acknowledgment of the vital role higher education plays in a democracy or the vast public benefit we all derive from an open and affordable college system. The debt that is now required to attend college has essentially commoditized and privatized what has been, since our nation’s founding, a public good.

A comprehensive solution to the student debt crisis is needed, but enacting a series of proposals that individually address the worst aspects of the trends—reducing interest rates for future borrowers, refinancing existing student loan debt at a lower interest rate, and reforming bankruptcy laws to allow for the discharge of student debt— would together have a significant impact. And action needs to happen now, before the country’s student debt burden reaches yet another terrible milestone.