Public financing of elections, as a state and local democracy reform, can help enhance the political voice and power of working-class people and people of color. It is an effective antidote to the outsized influence corporations and major donors currently have on both politics and policy. Today, an elite and tiny donor class—comprised of an extremely wealthy, 90 percent white, and overwhelmingly male subsection of the population – determines who runs for office, who wins elections, and what policies make it onto the agendas in Washington and state legislatures across the country.

In places like Connecticut and New York City public financing has helped elect candidates who successfully championed increasing the minimum wage, paid sick leave, banning employers from checking credit scores, and repealing the death penalty.

Public financing programs can, and should be designed to, achieve three key values: political equality, diverse and reflective representation, and increasing opportunity for exercising Independent Political Power—all of which are critical for giving people an equal say in the policies and decisions that directly affect their lives.

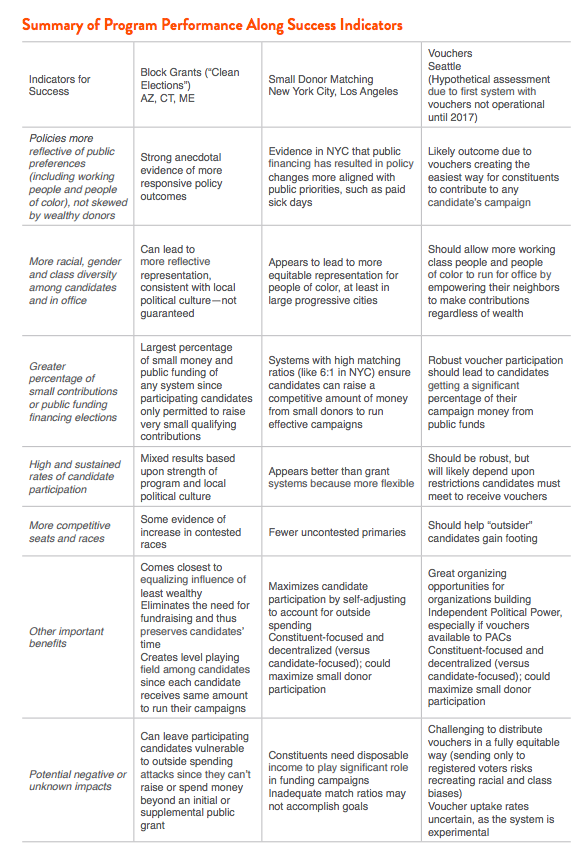

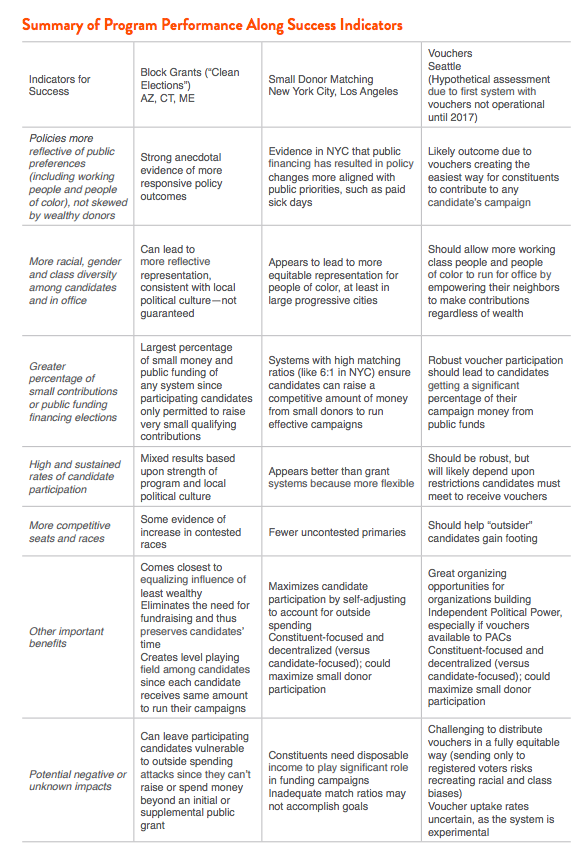

But not all public financing systems are created equal. Over the last few decades, three common types of public financing have been enacted, each with varying levels of success in fulfilling these core ideals and achieving specific indicators of a government by, of, and for the people. This brief provides a summary and assessment of the three most common types of public financing programs (block grants, small-donor matching and tax credits/refunds/vouchers) across a range of specific indicators tied to the values of political equality, reflective representation and exercising Independent Political Power:

- Better policy outcomes. Do city and/or state policy priorities more accurately reflect public preferences, including the needs of working class people and people of color, rather than being skewed by wealthy donors?

- More racial, gender, income, and wealth diversity among candidates and elected officials. Are more women, people of color, and working-class people running for office and winning?

- Greater percentage of small contributions financing elections. Are candidates raising money from large pools of small donors from their communities, as opposed to raising most of their campaign funds through large contributions from a handful of wealthy donors?

- High and sustained rates of candidate participation. Are most candidates opting to run their campaigns within the public financing system, and has participation in the system been sustained?

- More competitive seats and races. Is the political system more open and competitive, especially in primaries, so that constituents and their allied organizations can effectively hold elected officials accountable, and new candidates can effectively challenge the status quo?

Block Grant Programs

Grant-based programs—often referred to as “clean elections,” “fair elections” or “citizen-funded elections”—provide full funding for candidates to run their campaigns. Participating candidates receive a lump-sum grant from a public fund and no further fundraising is required (or allowed), so every participating candidate has equal resources with which to campaign. To qualify for the program, candidates must raise a threshold number of very small contributions (often $5) to demonstrate broad support in the community. To help participating candidates compete with big money opponents and unlimited outside spending, one jurisdiction has recently adjusted this model to allow candidates to receive a supplemental grant by securing a second round of qualifying contributions. Arizona, Connecticut, and Maine have statewide grant programs in effect.

Assessment

Grant-based programs generally ensure that campaigns are funded by the highest percentage of small dollars and public money and come closest to equalizing the voices of even the least well off (since all contributions to participating candidates are very small contributions); free candidates from spending the majority of their time fundraising (since fundraising is complete once the candidate qualifies for the grant, except for supplemental funding); and are best at equalizing the voices of candidates (versus voters) by giving them the same amount of money to conduct their campaigns—so campaigns can be contests of ideas promoted at roughly equal volume.

The biggest downside is that grant programs can leave participating candidates vulnerable to wealthy opponents and outside spending attacks since participants are generally not permitted to raise or spend money beyond the limited public grant, and (due to a bad Supreme Court case) cannot receive additional public funds to match opponent spending. In 2015, Maine updated its law with a strategy for addressing this problem by allowing candidates to qualify for supplemental funds by raising additional small-dollar contributions. Even with this adjustment, however, candidates must take a risk that public funding available (and the corresponding spending limit) will be adequate to keep up with an opponent. The system does not self-adjust by allowing candidates to keep raising small dollars to meet an unexpected surge of opposition spending.

It is difficult to draw firm across-the-board conclusions about the programs’ empirical impact on the key indicators listed above since there are only three statewide grant programs in effect in widely varying political circumstances (AZ, CT, ME).

Grant-based system should, in theory, lead to policy outcomes more in line with public preferences and less skewed by the donor class. There is good anecdotal evidence that a grant-based system has led to better policy outcomes in Connecticut, with less clear evidence in Maine or Arizona. The programs have appeared to increase racial diversity in Connecticut and have encouraged more women to run in Maine. Evidence shows that qualifying contributors in Arizona have been more racially and economically diverse than those to opt-out candidates. Arizona experienced an initial increase in Latino and Native American candidates but as participation has dropped off (see below), so too have the program’s benefits.

Participation rates have varied significantly. Participation in Connecticut’s system has remained robust—with 84% of winning legislative candidates participating in 2014. Participation has fallen off recently in Maine (53% of all general election candidates in 2014), leading to the 2015 initiative. Participation in Arizona has dropped off significantly since the program’s enactment in 1998, with only 25% of general election candidates participating in the most recent election cycle. This has been a result of both a 2011 Supreme Court case striking matching funds triggered by opponent or outside group spending and a significant increase in contribution limits in 2013. The varying degrees of participation are likely explained by a combination of the local political culture (Connecticut is much more progressive than Arizona, with Maine in between), the adequacy of public funding (and corresponding spending limits) in terms of making candidates feel they can participate and remain competitive, and the campaign finance that apply to opt-out candidates (higher contribution limits provide more of a temptation to opt out of the system).

The evidence on increased competition is mixed. Grant programs almost certainly increase the number of contested elections by lowering the barrier to entry for challengers. But, many races were uncontested either because the district is not competitive or there is a popular incumbent not particularly vulnerable to challenge (or both), so it is not always clear that more candidates translates into more highly competitive races. Nonetheless, additional candidates are reaching people not normally reached by privately financed candidates and could provide the building blocks for the creation of independent movements.

Small-donor Matching Programs

Matching fund programs match small contributions to qualifying candidates with public funds according to a specified ratio, which can be as high as six-to-one (in existing programs) or ten-to-one (in a proposed bill). This means that a $50 contribution from an individual donor can actually be worth $350 or more to a participating candidate. Under this system candidates continue to raise funds from small donors throughout their campaigns, constituents control the allocation of public funding with their own contributions, and candidates with more grassroots support will end up with more campaign funds than their rivals. To participate, candidates typically need to qualify by showing a threshold of support and then accept some restrictions (such as a spending limit and/or lower contribution limit); and there is usually a limit to the amount of public funds any candidate is eligible to receive. The goal is to amplify the voices of regular voters and thereby incentivize candidates to seek donations from a broad base of constituents rather than a few wealthy donors.

Several states and local governments provide some type of matching program. New York City and Los Angeles are the leading municipal programs; Montgomery County, MD recently passed a robust program; and the Government By the People Act is the leading federal legislative proposal.

Assessment

Small-donor matching public financing programs focus on amplifying the voices (and dollars) of low- and middle-income voters compared with wealthy donors, versus focusing on candidate parity. In this way, ordinary citizens actually have more control over which candidates get more public funding compared with programs that give equal grants. The biggest weakness of matching programs is that to participate effectively voters still need disposable income—more than Americans in poverty have to spare. In addition, the success of matching programs can vary greatly depending upon the size of the match, the total amount of public funding available, and the various restrictions participating candidates must agree to abide by (such as spending limits).

New York City and Los Angeles have robust municipal programs with high match ratios (6:1 and 4:1 respectively). While drawing across-the-board conclusions from this small sample is difficult, the lessons we can draw are directly applicable since these are two large, diverse, progressive cities.

Like grant programs, matching programs should lead to better policy outcomes by a) providing a viable path to office for those who lack access to wealthy donors; and b) motivating elected officials to spend more time with less wealthy constituents during (and between) campaigns. There is anecdotal evidence that the New York program, for example, has helped pass progressive policies such as paid sick leave. Yet in communities with low levels of wealth, candidates may need to go outside of the community for resources, potentially compromising the influence of their main voter constituencies and leading to less policy responsiveness.

New York’s program certainly appears to have diversified the donor base for city races. Both New York and Los Angeles have city councils that are even more diverse than their overall city population. The majority of the New York City Council is composed of people of color, and women also account for a high percentage of the Council’s membership. This suggests that small-donor matching programs are a good way to reduce entry barriers for candidates of color, and the level of funds at a 6:1 match is sufficient to provide them a decent shot of winning races.

How well matching programs perform regarding the percentage of small contributions in elections depends highly on the match ratio and the surrounding limits. A program with a high match ratio that matches only small contributions and a low contribution limit can lead to a significant percentage of small donor money. On the other hand, a low match ratio that matches the first dollar of a much larger allowed contribution will be much weaker on this scale.

Small-donor matching programs also appear to have a somewhat better track record than grant programs of attracting and sustaining high participation rates among candidates. More than 90% of primary candidates participated in the New York City program over the last two election cycles. This is at least in part because a well-designed matching system with a generous limit on public funding can self-adjust to a large influx of outside spending or big money opt-out candidates—participating candidates simply continue to raise small, matched contributions. But, again, it is difficult to make clear comparisons given the small sample size and varying political conditions. The matching program in New York City appears to have boosted competition generally, and led to fewer uncontested primaries.

Voucher, Tax Credit, and Refund Programs

Voucher programs provide a “coupon” to individuals to donate to a candidate (or sometimes a party or political committee) who can then redeem the voucher for campaign funds. Voucher programs can—but need not—require candidates to accept restrictions such as spending limits to qualify to receive vouchers. The first voucher program in the U.S. was passed through a ballot initiative in Seattle, Washington in November 2015 and will be operational in 2017. The Seattle system provides each voter registered in the City with four $25 vouchers to support her preferred candidates. Eligible contributors who are not registered voters will be able to apply for vouchers as well.

States and the federal government have experimented with various tax credit and contribution refund programs over the years. Tax credit programs generally allow those who file long-form tax returns to claim a full or partial credit for small political contributions made during the filing year to candidates and sometimes parties or PACs. The tax credit can be refundable (available to those without tax liability) or not. Minnesota has used a refund program where contributors can apply for a refund immediately and not wait until tax season.

Assessment

Voucher programs ideally combine the benefits of the grants system (giving even the least wealthy constituents an active role that does not require disposable income) and matching programs (constituents control where the public funding is directed so candidates have the ongoing incentive to reach out to people they typically ignore in the current system). Vouchers should perform well on all the indicators highlighted above, but since the Seattle system is not yet operational we do not yet have any empirical evidence. Key questions include: how many people will choose to use their vouchers, and will people who don’t receive them automatically (because they are not registered voters) be able to access them at decent rates. In addition, making PACs eligible to receive vouchers should drive participation (because more actors will be soliciting voucher contributions and therefore making people aware of the program) and help build Independent Political Power—but Seattle’s program does not permit this so we will not be able to assess it in the near future.

The research on tax credit and refund programs suggests that full (as opposed to partial) tax credits that are refundable and may be solicited by the maximum number of political actors (candidates, parties, PACs) are more successful at promoting the goals outlined above. The Minnesota refund program performed better than tax credits on these measures, and came closer to eliminating income as the primary factor driving whether someone contributes to campaigns. All of this evidence suggests that vouchers will perform better than tax credits and refund programs with respect to all of the priority metrics outlined above.

General Factors Affecting Program Success Across Models

As described in the sections above and the chart below, different public financing models have general strengths and weaknesses. But, it is critical to keep in mind that the programs’ effectiveness is also driven by several key factors that cut across models:

- How adequate is total and per-candidate public funding?

- What types of restrictions must candidates accept in order to participate in the program, and are candidates confident they can remain competitive within these restrictions?

- What campaign finance laws apply to opt-out candidates (high or low contribution limits, etc.)?

In addition to the campaign finance rules, there is another critical factor that governs how effectively a public finance system translates into the goals outlined in this memo: local political culture and infrastructure. Is the local culture progressive and participatory or anti-government? Does a city or state have a robust progressive infrastructure that is developed, aligned, and ready to take advantage of fair money in politics rules to help elect favorable candidates and hold public officials accountable? Strong infrastructure is much more likely to lead to success across indicators, including ultimately producing policy outcomes that are more responsive to working people and people of color.