Federal overtime standards are critical to protecting employees from working long, excessive hours. On July 1, the Labor Department’s rule to extend overtime protections to 4 million salaried workers went into effect. This win for workers comes after years of weak overtime standards.

In this brief, we’ll examine how conservative administrations, government inaction, and corporate interests have left low-paid salaried workers without adequate overtime protections for the past few decades.

Federal law establishes overtime protections but exempts many salaried workers.

More than eight decades ago, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) established overtime protections to help discourage employers from overworking their employees and to hire more workers instead. The law generally requires employers to pay covered employees at least 1.5 times their regular rate of pay for any hours worked over 40 in a workweek.

However, several statutory exemptions exclude workers from these critical protections.

An exemption commonly referred to as the “white-collar exemption” carves out those “employed in a bona fide executive, administrative, or professional capacity.” The statute expressly provides the Secretary of Labor the authority to “define and delimit” what this means.

For decades, weak overtime protections failed to protect low-paid salaried workers.

The Labor Department’s regulations require that white-collar exempt employees be (1) paid a fixed salary, (2) paid higher than a set salary level, and (3) perform certain job duties that demonstrate they are indeed executive, administrative, or professional employees. While the salary level and duties test have changed over the years, historically, these tests have worked together to separate “bona fide” white-collar workers who are exempt from non-exempt employees who should get overtime protections.

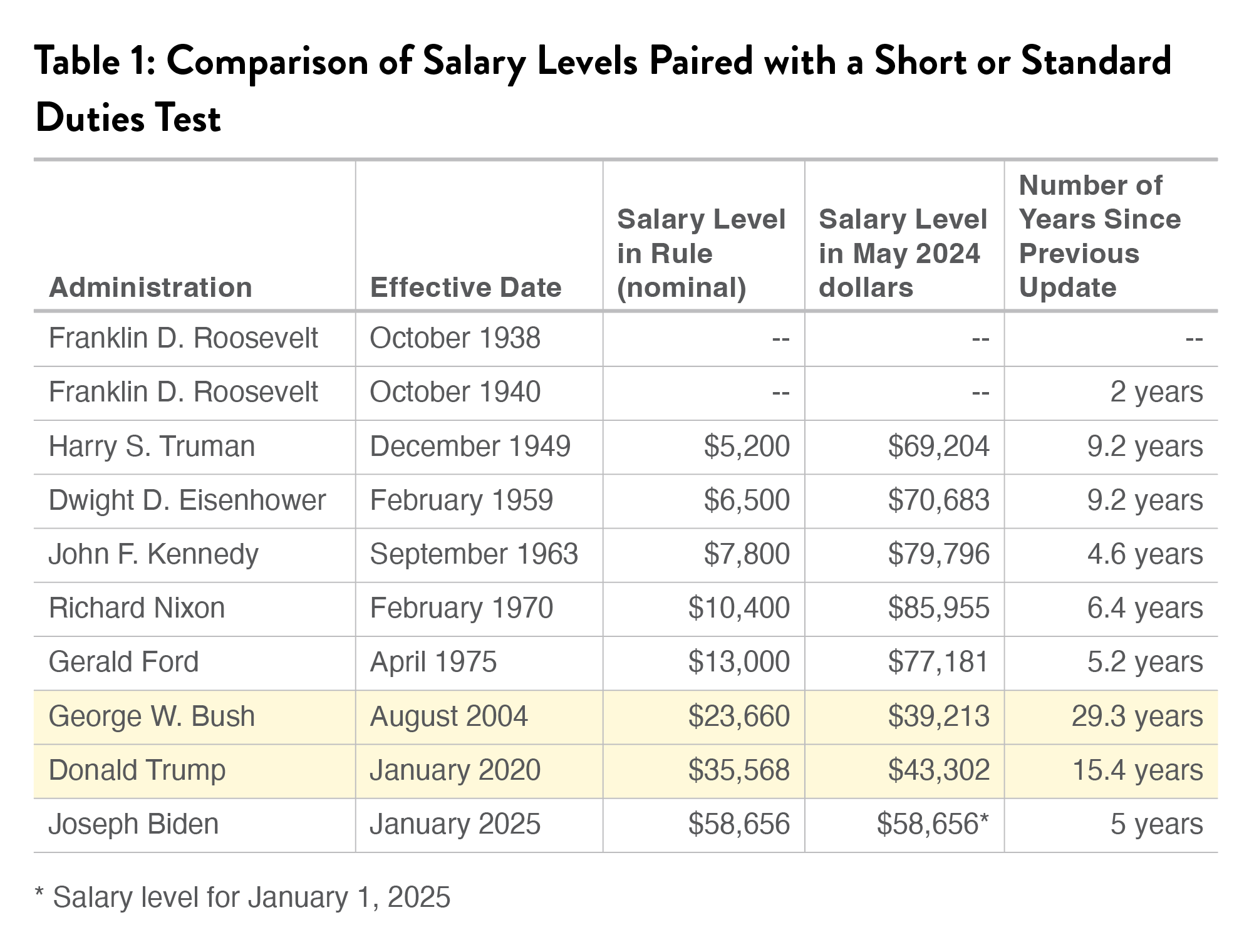

Before 1949, Labor Department regulations had lower salary requirements but a high standard for demonstrating an employee was performing white-collar job duties (referred to now as the “long test”). This prevented employers from claiming their low-paid salary employees were exempt by assigning them a minimal amount of white-collar job duties. Between 1949 and 2004, the Labor Department regulations also used an alternative approach that used a lower standard for duties (referred to as the “short test”) but required a higher salary that indicated that these workers were true white-collar workers.

Twenty years ago, conservative Administrations began using a flawed approach to updating overtime regulations, depriving millions of low-paid salaried workers of overtime protections.

In 2004, the George W. Bush Administration finalized a rule change that, for the first time in the rule’s history, used a deeply flawed approach that excluded too many workers from overtime protections. The 2004 Bush rule replaced the two balanced approaches used for the previous 55 years with one approach that paired a low salary level with a low standard for ensuring employees were performing white-collar duties (“standard test”). This mismatch meant that many employees who would normally be eligible for overtime because they were paid a low salary and performed little white-collar work became exempt. The Trump Administration used a similar approach in its 2020 rule.

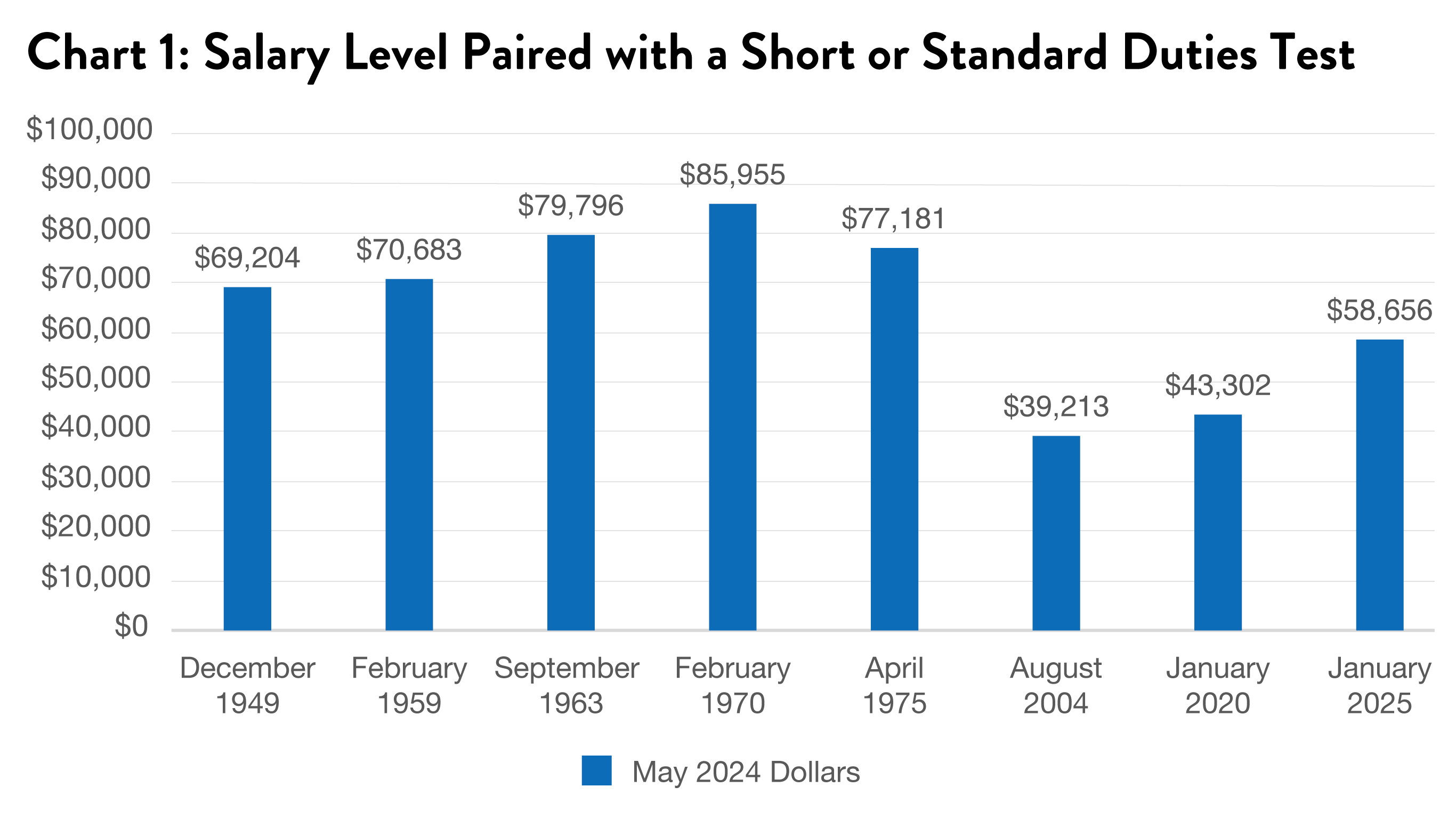

As shown in Chart 1, this approach resulted in two of the lowest salary levels used alongside a lower standard for duties (the standard or short duties test).

- In 2004, the George W. Bush Administration set the salary level at $23,660, which is the equivalent of $39,213 in May 2024 dollars.

- In 2020, the Trump Administration set the salary level at $35,568, which is equivalent to $43,302 in May 2024 dollars.

Workers have also endured decade-long periods without an update to the salary level.

Maintaining the real value of the salary level is critical. As the value of the salary level decreases with inflation and wage increases, so does its usefulness as a tool, along with the duties test, to determine whether an employee is truly a white-collar worker. While the Labor Department has updated its regulations nine times over the last 80 years to amend the salary level, these updates have been inconsistent and infrequent.

- Before 1975, the Labor Department waited an average of 6.1 years between updates, twice letting the salary level languish for 9.2 years.

- After the 1975 increase, nearly 30 years passed without an increase.

- After 2004, corporate interests challenged a 2016 rule (discussed below), so it would be another 15 years before workers saw an increase in the salary level.

Weak overtime standards allow employers to exploit employees.

Because the salary level was infrequently updated and conservative administrations used a flawed approach to defining the white-collar exemption for 20 years, employers could get away with overworking low-paid salaried workers by assigning them minimal white-collar job duties. A 2019 hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives provided real-world examples of how employers used weak overtime standards to exploit workers:

“Assistant Managers” at a restaurant chain who earn around $40,000/year and often work over 60 hours per week. They spend almost all their time running food to customer tables, expediting food orders, working in the kitchen, cleaning, and performing other non-managerial duties.

Dollar store “Manager” who earned approximately $38,000/year and regularly worked over 70 hours per week. She spent almost all of her time running the cash register, stocking shelves, waiting on customers, and doing the same type of work as the store’s hourly employees.

“Managers” at small convenience stores who generally earn annual salaries in the mid-$30,000’s and regularly work over 55 hours per week. They spent most of their work hours either alone in the store or with only one other store employee. They spend almost all of their time waiting on customers, running the register, cleaning, and performing other non-managerial jobs.

When the Labor Department has used a sound approach to increase the salary level in the last decade, corporate interests have turned to conservative courts to block stronger protections.

In May 2016, the Obama Administration finalized a rule that paired a higher salary level with the more lenient standards duties test for ensuring employees were performing white-collar duties. The rule set the salary level to $47,476 annually in 2016, with automatic updates every three years. A group of business groups and a coalition of conservative-led states separately sued the Department, seeking to invalidate the rule. One week before the final rule was set to go into effect, a federal judge in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas temporarily blocked the rule on a nationwide basis. Generally, the court held the Department did not have the authority to use a salary level as a test for the white-collar exemption. In August 2017, the same court permanently blocked the rule using the same reasoning.

But the Texas district court’s reasoning was at odds with congressional intent, regulatory history, and judicial precedent. Congress delegated to the Secretary wide authority to “define and delimit” the white-collar exemptions. Since 1938, the Department has used a salary level test. Even the Trump Administration defended its authority to use a salary test, pointing out to the Court of Appeals that every Circuit to have considered the question has upheld the Department’s use of a salary level.

Despite Legal Challenges, A New, Albeit Modest, Increase Went into Effect July 1, 2024

In April 2024, the Biden Administration finalized a rule that used the more lenient standard duties test paired with a more modest salary level: $43,888 on July 1, 2024, and $58,656 on January 1, 2025. This modest salary level sits between the higher salary levels used from 1949 to 2004 and in 2016 and the salary levels used in 2004 and 2019. While the 2024 salary level is far from the high-water mark, it is nonetheless an important step towards restoring overtime protections for low-paid salaried workers. According to Labor Department estimates, an estimated 1 million workers will gain overtime protections with the first adjustment on July 1, with another 3 million workers gaining protections when the salary level is fully phased in on January 1, 2025. Shortly after the rule was finalized, business groups and the state of Texas sued the Department, seeking to invalidate the rule.

The rule is in effect as of July 1 with one exception. On June 28, 2024, a Texas federal district court blocked the rule from applying to state employees, relying on the pivotal Supreme Court case, Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, issued the same day. In Loper Bright, the Supreme Court overturned Chevron deference—a 40-year-old legal doctrine that required courts to defer to expert agency interpretations of federal law, holding that courts must “exercise their independent judgment in deciding whether an agency has acted within its statutory authority.” This recent ruling underscores a significant shift in judicial authority, mandating courts to independently evaluate agency actions without the automatic deference previously afforded under Chevron.

Conclusion

All workers deserve the right to earn a living without being overworked. Over the last few decades, conservative policymakers and corporate interests have opposed strong overtime protections. The Biden Administration’s overtime rule offers a step towards restoring overtime protections for millions of salaried workers.