Sandwiched between its controversial immigration, campaign finance and health-carerulings last month, the Supreme Court issued a little-noticed decision in a Maryland case that gave the green light to states to eliminate the repugnant practice of “prison-based gerrymandering.”

States are now unquestionably free to correct for an ancient flaw in the U.S. Census that counts incarcerated people as residents not of their homes but of the places where their prisons are located. When the prison population was small, the problem was little more than statistical trivia. Today, however, the census counts more than 2 million people as though they were residents of places where they have no community ties.

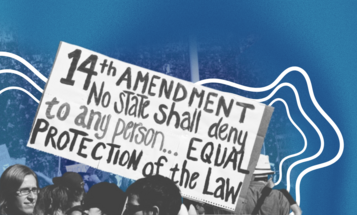

In a June 25 summary disposition of the case Fletcher v. Lamone , the court upheld Maryland’s landmark 2010 “No Representation Without Population Act,” which does what the Census Bureau would not: count incarcerated people at home for redistricting purposes. Maryland was the first state to recognize that the bureau’s method of counting people in prison resulted in a systematic transfer of political clout that undermined the constitutional principle of “one person, one vote.”

As a 2010 report I presented to the Legislative Black Caucus of Maryland showed, after the 2000 Census Maryland drew one state legislative district that was 18 percent incarcerated. The result was to give every four people who lived near the cluster of prisons in Hagerstown the same representation in Annapolis as five from any other district in the state. While urban and African American communities bore the brunt of the harm, prison-based gerrymandering diluted the votes of residents of communities across the state.