What the Washington Post Editorial Board Gets Wrong on Student Debt

Since student debt, free tuition, and debt-free higher education have emerged as presidential campaign-level issues, a narrative has begun to emerge among elite media that the rising price of college and ever-increasing student debt are phantom problems given the overall lifetime benefits of a college degree. An editorial in yesterday’s Washington Post, titled “Democrats’ Loose Talk on Student Loans” crystallizes this narrative, making the case that we have more of a nuisance than a crisis on our hands, and that bold reforms to address it—including the plan offered up by Secretary Clinton’s campaign—are overkill, and that we should presumably make large investments in other areas (like paying down the national debt).

Unfortunately this argument, which has also been featured to varying degrees in both NPR and Vox over the past few weeks, rests on a pretty narrow set of assumptions about college and its benefits, and in fact misunderstands the entire point behind the push for debt-free public college.

First, a few facts. It is absolutely true that some form of postsecondary education and training has become more important, and nearly essential, in today’s workforce. Unemployment rates for college graduates are consistently low, and the average lifetime earnings boost remains high relative to a high school degree. Anyone who argues that college “isn’t worth it” is doing so with anecdotal examples or bad data.

But the reason college is so important is not because earnings for college graduates keep rising. In fact, bachelor’s degree-holders earn about the same amount as they did 30 years ago. Earnings for everyone else—including those with only some college experience—have gone down rapidly. In effect, a degree has become more a necessary insurance policy than an investment.

This matters, because students are now on the hook for financing more and more of their own education than ever before. So graduates are taking on rising levels of debt while contending with stagnant incomes, the rising cost of healthcare and childcare, all while attempting to save for retirement or for their own child’s education.

And these are some of the best-off of the bunch—they’re able to stretch and make their minimum monthly payments. The true crisis in student loans is among those who take on student debt but do not graduate, many of whom attend high-cost for-profit institutions. These students are more likely to default or become delinquent on student loans, potentially setting themselves up for a lifetime of economic hardship. But while some argue that what we really have is a “completion crisis,” college completion is no better or worse than it’s been in decades.

The difference now is that, unlike the early 1990s, most students must borrow for a degree. In other words, we have increased the risk of attending college, simultaneously telling students that they must go to college to ensure financial security while dialing up the potential for financial catastrophe if they cannot complete.

Completion and debt are also not mutually exclusive, as some might have you believe. Students drop out of college for many reasons, but the most common reasons cited are financial—debt, high cost, the need attend part-time while juggling a full-time job. This means that, if we care about increasing college attainment, we must first deal with the financial pressure facing students who either decide not to go or feel they cannot finish. Guaranteeing a debt-free pathway to a degree can lower the risk of not graduating and help more students graduate.

On a macro level, the Post and others have seized on a report from the White House Council of Economic Advisors, the key takeaway of which was that providing students with access to loans allowed many to go to college during the recession, leaving them much better off than had they not attended at all. This report tells us much of what we already know—that providing a financing mechanism for students is better than nothing at all, that student loans make up a relatively small share of the overall economy, but that for many students (including the 7 million in default) it has become a crisis.

But those arguing that this means student debt is not a major policy problem have the counterfactual all wrong. Essentially, the report is arguing that providing students money to pay tuition bills and thus go to college is a good bet. But this is more true of need-based grant and scholarship aid than it is of loans. Grants have proven time and again to increase access, retention, and completion, while research on loans is mixed. Further, grant aid, since it does not need to be paid off, does not carry with it the risk of student loans, which is an extremely important difference in an era of stagnant college completion rates and stagnant incomes for graduates.

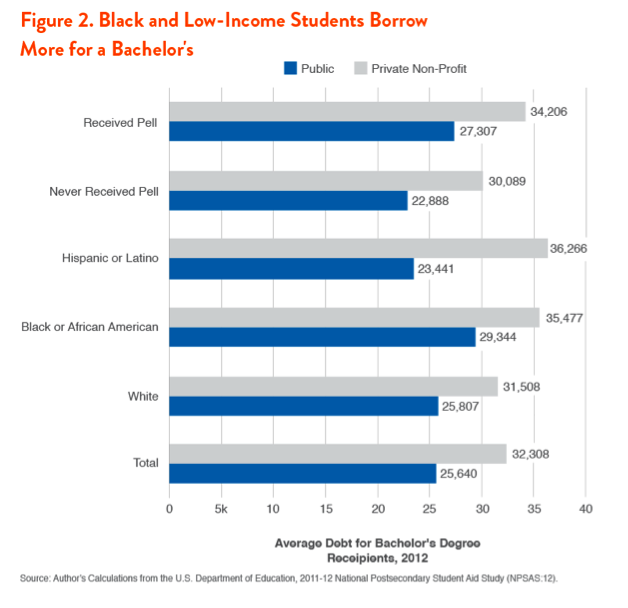

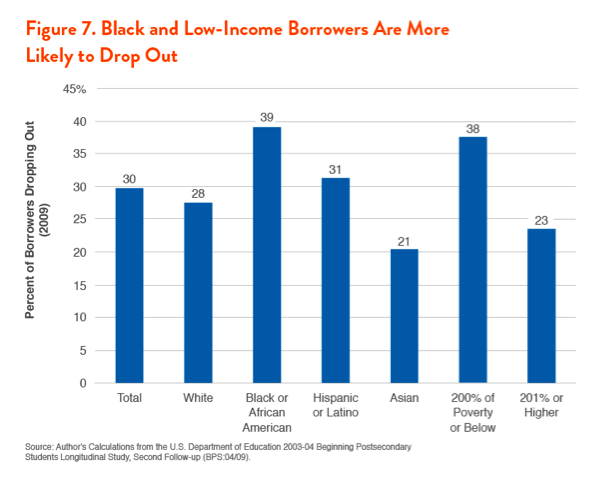

And unfortunately, the media often misses that student debt is a problem with a color and class element. We know that black borrowers take on more debt for the same degree as white students, and are more likely to drop out with debt.

But black and Latino students also do not see the same benefits of a degree either. Unemployment for black college graduates is the same as white high school graduates, average earnings are lower for black workers than white workers at every level of education, and the average wealth of a black college graduate equals that of a white high school dropout. Read that sentence again.

The fact that half of young black households have student debt, and are more likely to have student debt than young white households, means that even if they are better off going to college than not, white families will continue to have an unearned leg up in the economy. Regardless of the amount they have taken on, borrowers of color are the face of this crisis.

Society benefits from an educated population, which is why we invest in it. It’s why the GI Bill, warts and all, returned $7 for every $1 invested and is considered a massive success. It’s why public investment in a degree reaps tens of thousands of dollars in return.

When we individualize the benefits of college, we miss the forest for the trees. It’s striking that we do this for college and not other forms of education. We do not send 5-year-olds home from kindergarten with $20,000 tuition bills, justifying it by saying that the alternative of not going to school is worse. We do this because it’s in the public interest to send students to school without financial barriers and that the alternative would impose massive barriers based on race and class.

It is, of course, important that we provide relief to those who are most likely to struggle with debt and those who do not see the returns from college. The concept of debt-free college does just that, by asking students to work hard and maybe take on a part-time job, states to chip in like they did for previous generations, and the federal government to treat higher education as a public good again. It is progressive—asking the wealthy to pay their fair share while eliminating unmet need that cripples the ability of low-income students to pay tuition bills. It reduces risk and expands opportunity.

Those of us concerned with student debt are not saying that students should avoid college, any more than we would complain about high rent and recommend homelessness instead. Instead, we want to remove the financial burden from those most afflicted and ensure that the next generation making college-going decisions doesn’t avoid it because their family can’t afford it.

Update

I would be remiss if I didn't mention all the stellar reporting on student debt and higher education issues by the Post's Danielle Douglas-Gabriel. She has followed the issues of racial equity in student debt, as well as state higher ed cuts, doggedly. In fact, her clear grasp of some of the nuances and peculiarities of these issues make yesterday's piece by the editorial board even more frustrating (there was in-house expertise, after all). Anyway, please do read her work here.