The Third Reconstruction: Looking Beyond the Emergencies of Today to the Beloved Community

In his synthesis of Dēmos' Third Reconstruction series, Aron Goldman explains how each voice contributes to a bold and ambitious vision beyond the emergencies of today, helping us imagine and lay the foundation for the next chapter of American history.

“Toward a Third Reconstruction” is a six-part Dēmos/Nonprofit Quarterly series, published between November and December, 2025, drawing on the defiantly optimistic vision of nine experts, activists, and leaders (in chronological order): Peniel Joseph, Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values at the Lyndon Baines Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin and Founding Director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy; Darrick Hamilton, Henry Cohen Professor of Economics and Urban Policy and Founding Director of the Institute on Race, Power, and Political Economy at The New School; Dorian Warren, Co-president of Community Change and Co-founder of the Economic Security Project; Analilia Mejia and DaMareo Cooper, Co-executive Directors at the Center for Popular Democracy; Sulma Arias, Executive Director of the People’s Action Institute and People’s Action; Carmen Rojas, President and CEO of the Marguerite Casey Foundation; Richard Besser, President and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; and Taifa Smith Butler, President of Dēmos. The following synthesis explains how each voice contributes to a bold and ambitious vision beyond the emergencies of today, helping us imagine and lay the foundation for the next chapter of American history.

Dreams

In his “Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination,” Robin D.G. Kelley explains that “a map to the new world is in the imagination.”

There are so many emergencies right now—ICE abductions, decriminalization of anti-Black racism, the political hijack of the struggle against antisemitism and anti-Blackness, unauthorized military aggression abroad, a climate crisis accelerated—that it’s hard to know where to direct our resistance. Struggling just to mitigate the most inhumane and violent symptoms of the current regime, where do we find the energy, spirit, and vision to build an entirely new system? Kelley tells us where to look.

We are challenged to go beyond palliatives and to not settle for targeted and narrow technocratic solutions either. Even in the worst of times, Kelley explains, the Black experience demonstrates what may be true for humanity: The instinct for freedom is immutable.

This instinct guides the series, “Toward a Third Reconstruction,” produced by Dēmos, Nonprofit Quarterly, and me. The audacity of that project is to imagine a new world, even when there is every reason to believe that mitigating strategies, incremental approaches, and “big tent” compromises on core values are the only realistic options. In this way, this series confronts not only the conspicuous tyranny of our time but our own invisible assumptions and self-imposed constraints as well.

In order to stop authoritarianism, we must explicitly confront the white supremacy that animates it.

Marcus Garvey’s challenge (immortalized in Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song”) is to “emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind.” What does that internal emancipation look like for experts, activists, and leaders at this moment? And where does it lead? Below, I try to illuminate and interconnect the brave perspectives of each of the nine authors. Cumulatively, they show how this moment is a continuation of a centuries-long struggle, that in order to stop authoritarianism, we must explicitly confront the white supremacy that animates it, and that economic power, democracy reform, and racial justice are inextricably linked.

We’ve been here before

The first leap is temporal. Peniel Joseph launches the series by contextualizing an extraordinary moment in historical cycles of oppression, progress, and backlash that define American history. This is a uniquely horrifying experience for many of us, but as a nation, we’ve been here before.

With the benefit of historical context, it’s clear that now is the time to anticipate the next historical phase and begin building the structure of a better society. Combining historical perspective and bold vision means continuing the unfinished work of the Second Reconstruction (also known as the Civil Rights Movement), which in turn sought to continue the work of the First Reconstruction (associated with the abolition of slavery), which in turn sought to more fully realize the nation’s founding revolutionary ideals (enshrined in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights).

We have already had glimpses. The election of Barack Obama in 2009 and the birth and expansion of the Black Lives Matter movement from 2012 to 2020 showed that people can be mobilized to resist white supremacy and pursue a reconstruction. Yet, instead of ushering in structural changes and a renewal of a sustained national consensus around racial equity, the ascendance of Donald Trump represented a swift and brutal backlash of historic proportions. “Toward a Third Reconstruction” demonstrates that, even in a dark hour, our dreams of freedom are grounded in a singular and ongoing project that is the story of this nation.

Reinventing racial justice

Without an honest acknowledgement of white supremacy as the doctrine that delivered us here and, as Dēmos CEO Taifa Butler explains in the series’ capstone piece, “the anti-Blackness that animates it,” we will not overcome authoritarianism. The criminalization of the analysis of and struggle against racism has caused individuals and institutions to censor themselves. Some explain that they have scrubbed triggering terminology from their websites to avoid attracting unwanted attention, but they are continuing the work. That is easier said than done. And in many cases, the work has in fact gone missing. The fact is that DEI jargon was never the point, and it was often a stand-in for the meaningful work needed to actually combat deeply embedded structural racism. Now that performative DEI has no currency, this is the moment to support institutions that are genuinely committed to racial equity to operationalize their values and their vision.

In the racial equity institutional capacity-building work that I do, we talk about "blaming systems, not people.” While we are certainly witnessing an alarming proliferation of explicit interpersonal racism and hate targeting several vulnerable groups, a structural analysis helps us see the ways in which policies, systems, physical infrastructure, and social and institutional culture have a profoundly disparate impact on people’s lives. These impacts reinforce and exacerbate unequal outcomes that, in some parts of America, make it appear that the Civil Rights Movement never happened. A new national consensus around racial equity must expand the understanding of racism endemic to the civil rights era to include structural analysis.

One implication of blaming systems is that none of us are immune to the influence of white normative behavior. Borrowing a metaphor from author Tema Okun, as Americans, racism is in the air we breathe. Those invisible norms that unwittingly constrain our own thoughts and actions include the cultural legacy of narrow technocratic analysis and problem-solving that have failed to capture the imaginations of American voters. Eschewing things like dignity, agency, spirit, and culture as “too soft” or “not rigorous” means only policy wonks mobilize. And the mantle and momentum of populism are lost to the right.

The work of Robin D.G. Kelly, Ruha Benjamin, and others has helped disrupt these norms, challenge notions of acceptability, and open the door to creativity, imagination, artistic expression, and futurism. These critical approaches owe their origins to the Civil Rights Movement, while evolving and opening up opportunities for the kind of seismic changes worthy of a Third Reconstruction.

Re-centering racial justice also means building solidarity among identity groups that have historically or are currently experiencing oppression—and engaging effectively with white allies.

The working class versus the cult of identity politics, for example, is a false dichotomy that has become a deeply embedded narrative. Similar to Ronald Reagan’s immortal “welfare queen,” this narrative has colonized our minds, conjuring images of, on the one hand, white steel workers building things while Black and brown people sit around and complain.

As Taifa Butler and Carol Lautier, Dēmos’ Director of Movement Building, explain in a recent opinion piece, “this dichotomy is a dog whistle signaling a zero-sum dynamic where any gains for Black and brown people will be at the expense of white people proportionately (and vice versa).”

But for starters, working-class people are people of color. Within twenty years, it is estimated that the U.S. will be majority-minority (seven states, plus Washington, D.C., and all U.S. territories, already are).

Next, focusing on any demonstrably underserved population (Black people, women, people with disabilities, the LGBTQ+ community), provides a safety net that protects everyone.

And finally, to maximize overall productivity, we must be able to maximize the full potential of the workforce, free from any market distortions that the implicit or explicit biases of employers, policymakers, and others may cause. These biases exist because we are human and live in a culture rooted in racism. Ignoring them only hinders overall progress. This reality undermines another false dichotomy that has seeped into the current narrative: meritocracy versus DEI.

According to Darrick Hamilton and Dorian Warren in the second contribution to this series, “Solidarity is not a transaction. It is a durable, moral commitment to collective liberation that recognizes our fates as interconnected and our struggles as ultimately indivisible.”

Building economic power

Race and class are inextricable. Power is what binds them. Channeling W.E.B. Du Bois, Hamilton and Warren explain that “concentrated wealth is concentrated power, and concentrated power is fundamentally incompatible with multiracial democracy ….”

It is very hard to look up at the horizon in pursuit of structural change when you are looking down to satisfy immediate needs.

The Dēmos Power Scorecard, which cross-references economic security and civic engagement indicators, demonstrates that Americans worried about paying for groceries, housing, and medical bills are also the ones who have no voice. It is very hard to look up at the horizon in pursuit of structural change when you are looking down to satisfy immediate needs.

The renewal of the labor movement may be the most powerful lever to reassert power for working people and confront the corporate capture of government. Organized labor also represents the opportunity to take back the notion of populism. In the place of race-baiting, fearmongering, and conspiracy theories, restoring constitutional rights and then boldly expanding them to include rights to housing, health care, education, child care, and environmental justice is a populist agenda worthy of a Third Reconstruction.

When government retreats, or when it becomes a threat to its own people, philanthropy also has a critical role to play. Philanthropy is not a substitute for a social safety net, but in the face of a rising autocracy, resources must be mobilized quickly—and without the paternalism that is thinly veiled by a “culture of accountability.” In the fifth installment of the series, Carmen Rojas and Richard Besser position the sector as a critical response to the autocracy playbook, the disruption of which is essential to the formulation of a Third Reconstruction.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Truth, Repair, and Transformation process is also showcased in this installment as a model for rethinking philanthropy at a fundamental level. If we acknowledge that the scale of wealth that philanthropy collectively represents could not have been accumulated without various forms of exploitation at various points in time, then grantmaking is really the exercise of returning wealth to the communities it was extracted from as expeditiously as possible. Isn’t that “reparations”? Turning the fundamental narrative of philanthropy upside down has enormous potential to disrupt traditional economic power dynamics and fuel a Third Reconstruction. RWJF’s process isn’t there yet, but this is the direction it is headed.

Democratic reform

The transformative promise of the First Reconstruction, represented by the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, was dismantled by the Jim Crow era backlash. The Second Reconstruction (the civil rights era) used the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to reclaim those amendments and reassert the aspirations of the First Reconstruction. But as part of the cruel irony of the backlash to the Second Reconstruction, the courts have been mobilized to reinterpret elements of those amendments to mean the exact opposite of their original intent.

More specifically, Analilia Mejia and DaMareo Cooper explain in their contribution to this series how key elements of the 14th Amendment have been distorted:

- “Equal protection” (and Section 1981 in particular) has been used to invent and inculcate the concept of “reverse discrimination” in order to outlaw affirmative action and race-explicit decision-making.

- Due process has been sidestepped in order to terrorize immigrant communities and separate families using indiscriminate raids and extrajudicial rendition (also known as “disappearing”).

- Challenging one of the most sacred elements of the Constitution, as well as the cornerstone of slavery abolition and voting rights, birthright citizenship is being challenged with some initial success.

Just as the Second Reconstruction used the Voting Rights Act to reinforce the 14th Amendment, the Third Reconstruction must reestablish the integrity and inviolability of the 14th Amendment using the courts, legislation, executive leadership, and working-class mobilization.

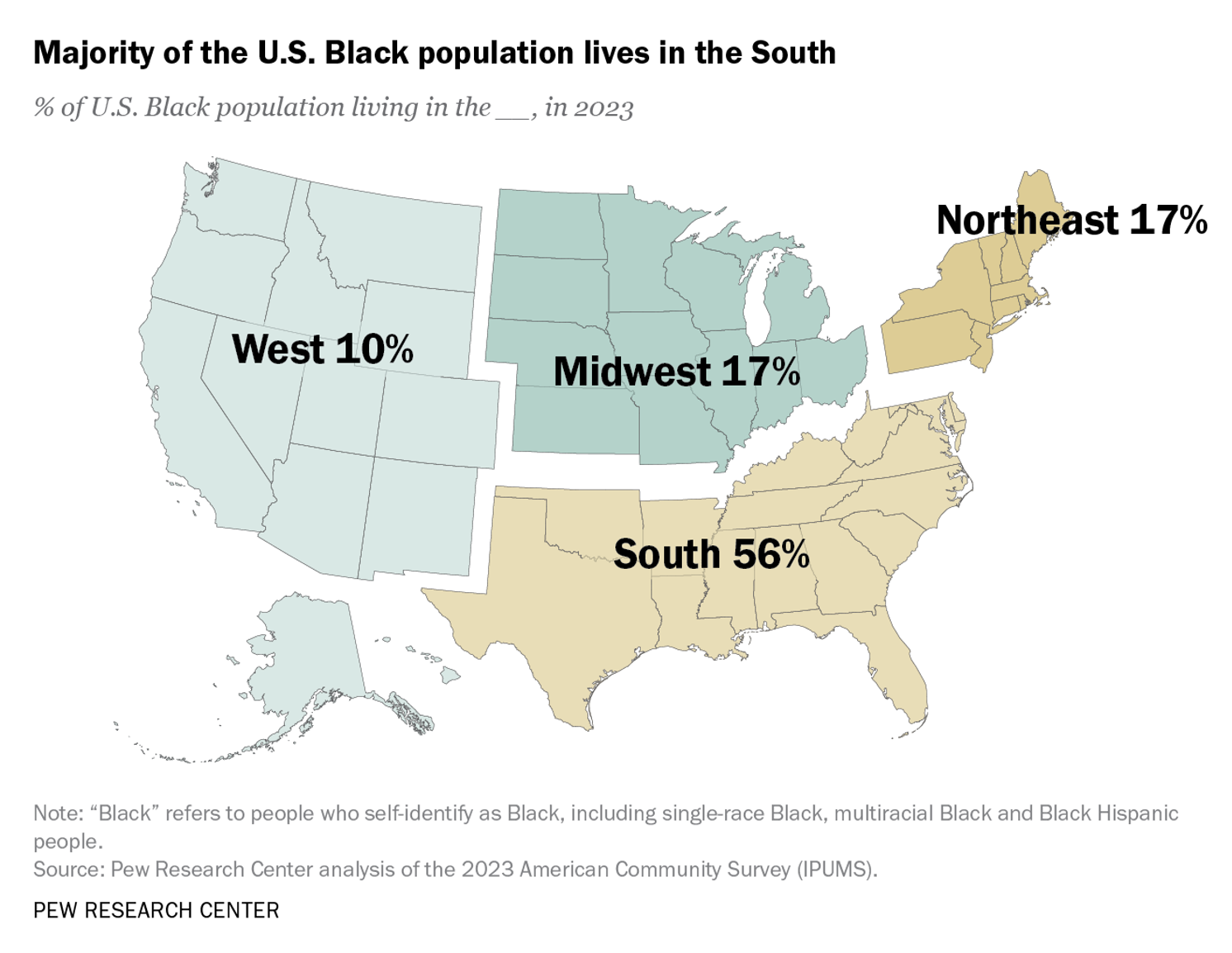

The Third Reconstruction must also continue the work of the First and Second Reconstructions by refocusing on the South. While most Black Americans (56%) live in the South, most legal and financial resources (public and private) are in the Northeast. This structural disparity must be recognized and remedied at the federal level.

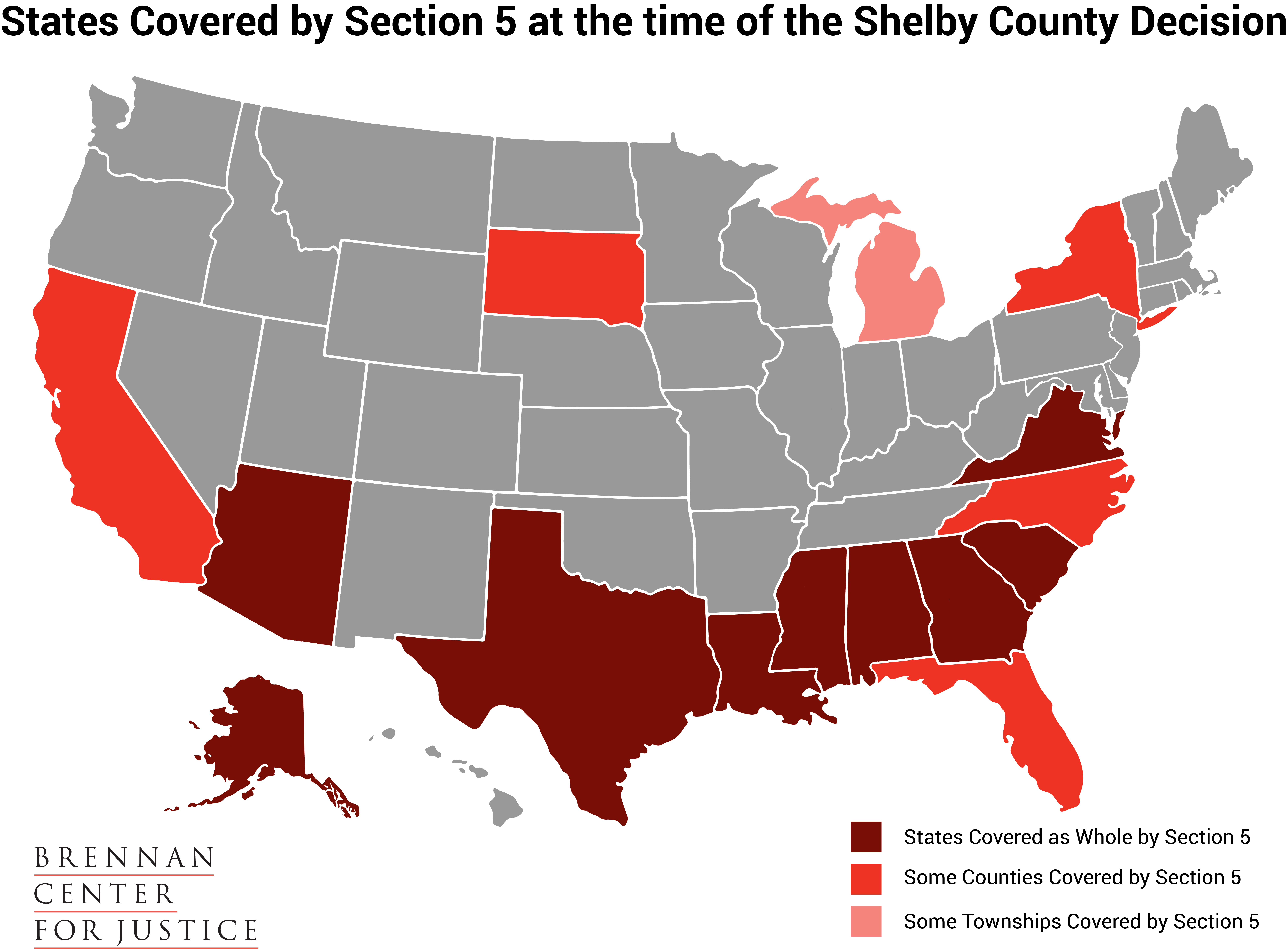

One important example is the Voting Rights Act, which lost its critical Section 5 “preclearance” provisions in the 2013 Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder. This special status for nine states with large Black populations and long histories of voter suppression and disenfranchisement (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia) required extra levels of federal oversight for state and local voting laws that could be used to maintain or increase inequality. Absent these preclearance provisions, voter suppression laws have taken root again, actual voting disparities have increased sharply, and with the Supreme Court’s 2025-2026 docket including “reverse discrimination” cases that challenge voting rights efforts in Southern states, we can expect continued regression.

While the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act (first introduced in 2021) is one effort to restore voting rights protections, the Third Reconstruction will require a more expansive effort to redirect attention and resources to Southern states in the context of an explicit and universal commitment to racial justice and the political power of Black and brown communities.

Conclusion: The Beloved Community

The neoliberal order, originating in the Reagan era and defined by free markets and minimal government intervention, is unquestionably over. What will fill the vacuum?

President Trump’s audacious proposal, rooted in white supremacy, is on display. And his aggressive consolidation of power helps ensure that neither adverse results for non-elites, nor even actions that violate federal or international law, will pose a threat.

But as Sulma Arias points out in the fourth installment of this series, “Winning does not mean simply removing authoritarians and white supremacists from power.”

A Third Reconstruction must offer its own alternative to the Trump agenda.

A Third Reconstruction must offer its own alternative to the Trump agenda. Dr. King’s unrealized vision of a Beloved Community is poised to be just that. This paradigm combines a re-centering of racial justice, economic power building, and democratic reform. And, as Taifa Butler explains in the final installment of the series, “... the beloved community can also count on having less tangible, but not less important, things: dignity, agency, compassion, and the spiritual liberation that comes when a chronic fear of wanting for basic needs is eliminated.”

Right now, Minneapolis is the front line of a bloody ground war and resistance against authoritarianism and white supremacy. The contributors to this series, “Toward a Third Reconstruction,” show how to organize our institutions and our communities to ensure that the deaths of Keith Porter Jr., Renee Good, Alex Pretti, and others are not in vain, that the struggle stays true to its historic legacy, and that it delivers us to a new world built of three pillars: new norms, new institutions, and new forms of power.