Stock Market Highs Reveal Racial Economic Divides, Not Broad Prosperity

A strong economy cannot be measured by stock market performance; it must be assessed by everyday people’s ability to meet their basic needs and achieve economic security.

Tomorrow, we’ll get the latest jobs report, which will include fresh data on key labor market indicators that reveal how our economy is performing. Escalating unemployment rates among Black workers, along with slowing job growth and elevated inflation, signal a concerning underlying weakness in today's economy.

Although a rising stock market is often cited as evidence of a strong economy, it doesn't reflect the reality many people experience.

Yet President Trump insists that the economy is strong. Narrowly focused on indicators like the S&P 500, he has dismissed what he calls an exaggerated "affordability crisis," ignoring the real pressures families are experiencing every day. Although a rising stock market is often cited as evidence of a strong economy, it doesn't reflect the reality many people experience. In addition to reflecting activity in financial markets, stock market highs can tell us something about how people are living, but they primarily reflect the financial well-being of mostly white and wealthy families at the very top. Because stock market participation is so varied by race and class, it doesn’t reflect the economic conditions many experience.

Stock ownership, and the benefits that flow from it, are heavily skewed toward the wealthiest households. While 58 percent of households own stock either directly or indirectly, that headline number obscures deep disparities. The wealthier you are, the more likely you are to own stock in the first place, and the more valuable those holdings are. As a result, when the stock market rises, the benefits concentrate among households with the highest incomes and largest portfolios.

Stock market gains yield substantially larger windfalls for white families, widening divides that have been built and reinforced over generations.

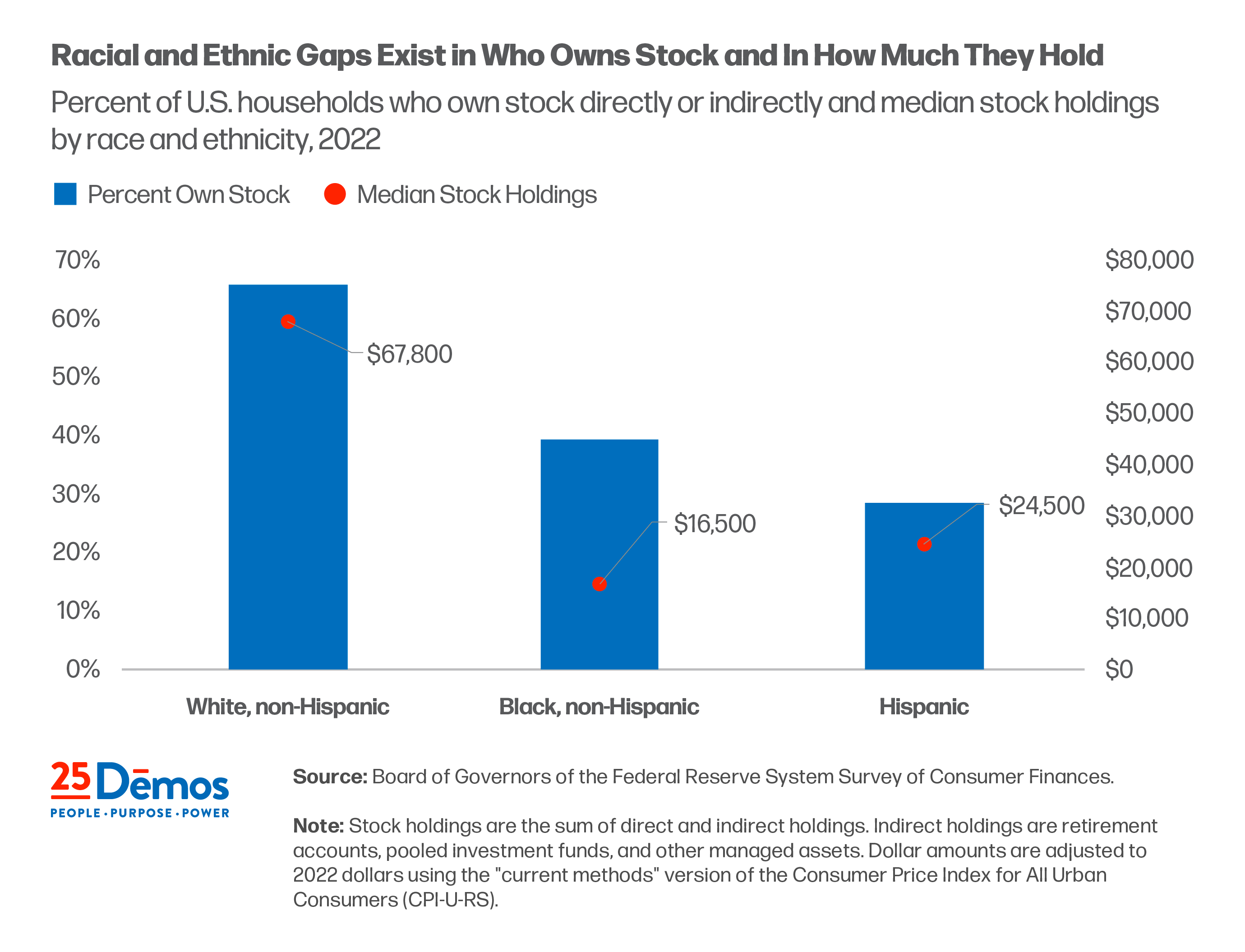

These inequities are not only about wealth. They are also deeply shaped by race. The figure below illustrates this: The bars show the share of households that own stock by race, and the dots represent the median value of their stock holdings. As the figure shows, white households are more likely to own stocks and to own them in significantly higher amounts. For example, 66 percent of white households hold stocks compared to just 28 percent of Hispanic households. Even among households that do own stock, the value of those holdings differs sharply by race. For example, the median value of stock holdings for white households is $67,800, while for Black households it is just $16,500. This means that stock market gains yield substantially larger windfalls for white families, widening divides that have been built and reinforced over generations.

Families continue to face high prices for essentials such as rent, utilities, and child care, pressures that the stock market does little to reflect.

Understanding who owns stock and how unequally those holdings are distributed helps us clarify what the stock market actually signals. A rising stock market doesn't necessarily mean households are doing well. Families continue to face high prices for essentials such as rent, utilities, and child care, pressures that the stock market does little to reflect. What it largely does is indicate gains for households that already hold wealth. When policymakers rely on stock market performance rather than people-centered economic data, real hardship is easily obscured.

The stock market may be performing well, but that doesn't mean the economy is performing well. To understand real economic conditions, we must look beyond markets and toward indicators that reflect the reality of people’s lives.

Tomorrow's jobs report will offer a stark reminder: Stock market gains cannot disguise the economic hardship countless families are facing.