Looking Beyond the Headline Unemployment Rate: Why the U-6 Underemployment Rate Matters

As 2026 employment data rolls out and we try to make sense of the new year's economy, the U-6 rate offers a less-cited but revealing indicator of labor market health.

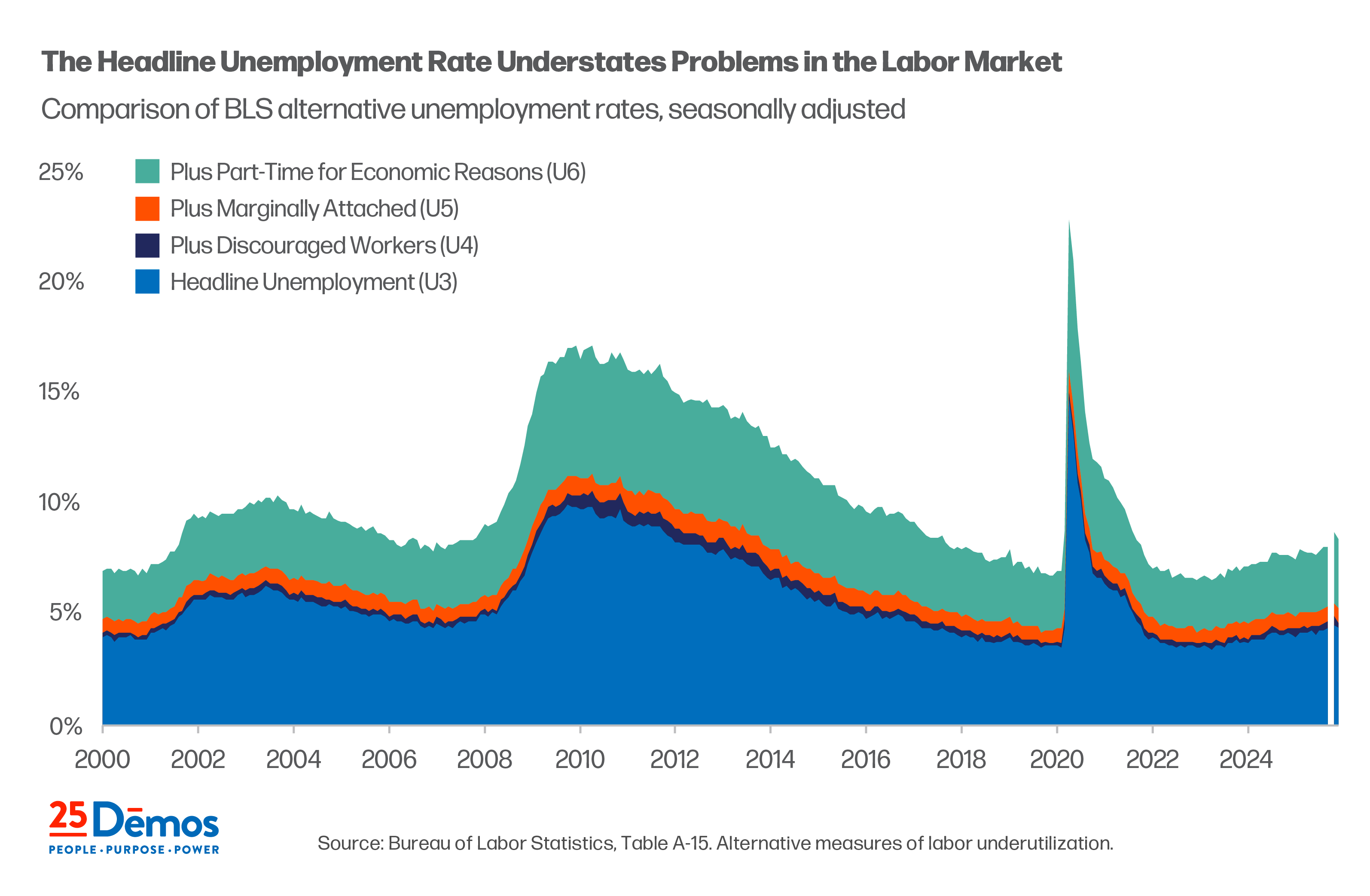

Next week, the first economic data of 2026 will be released, and attention will focus, as it usually does, on the headline unemployment rate. While that number does offer a snapshot of who is officially out of work in the economy, it accounts only for jobless people who have looked for work in the past four weeks, and it therefore misses some key dimensions of labor market strain that shape how people actually experience the economy.

"Is everyone who has a job working as much as they want to be?"

Diagnosing the state of the labor market requires that we look beyond whether jobless people are actively searching for work, and instead ask, "Does everyone who wants a job have one?" and "Is everyone who has a job working as much as they want to be?" To better understand the fuller picture, we should turn to another data point, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics labels as the U-6 measure. The U-6 captures those who are unemployed and also people who want to work but have stopped actively looking, as well as people working part-time even though they want to work full-time.

By including these workers, the U-6 rate shows how many people want to work (or want to work more) but are not able to, and how much opportunity the economy is missing when people who want to contribute paid labor are left out. This fuller picture reveals labor market strain that the headline unemployment rate alone doesn't capture.

Black and Hispanic workers are more likely to be underemployed, and they consistently face higher unemployment rates than their white counterparts.

Underemployment, such as being stuck in multiple part-time jobs or stepping out of the labor force after encountering repeated barriers, can have serious negative economic effects on workers and families. For example, if someone wants to work more but is limited by an employer’s scheduling practices or a lack of full-time opportunities, they may not be able to cover bills, handle unexpected expenses, or build savings. An analysis of 2018 census data showed that a quarter of involuntary part-time workers lived in poverty. Digging into the demographic breakdown, we also see that Black and Hispanic workers are more likely to be underemployed, and they consistently face higher unemployment rates than their white counterparts. This pattern both reflects and compounds longstanding inequities in the economy, highlighting how structural barriers continue to shape who has access to stable, adequate work.

The most recent economic data shows that both the headline unemployment rate and U-6 rate have been edging up, but the increase in the U-6 rate has been sharper, signaling that slack or unused capacity in the labor market is growing faster than the headline rate suggests. This widening gap points to the rising strain under the surface, as more people are working fewer hours than they want or have stepped back from actively seeking a job after facing limited opportunities, including barriers like discrimination. As 2026 data rolls out and pundits, policymakers, and the public try to make sense of the new year's economy, the U-6 rate offers an important, but less frequently highlighted signal of labor market stress.

Unemployment and underemployment are not accidents; they reflect policy choices.

Unemployment and underemployment are not accidents; they reflect policy choices. An economy that tolerates persistent joblessness and involuntary underemployment keeps too many workers, especially Black and brown women, stuck in precarious positions by design. This includes both paid work and the disproportionate share of unpaid labor that women are expected to shoulder. By measuring how many people who want work but can’t, or are unable to access full-time work, the U-6 rate highlights the broader labor market mismatch. It's a reminder that building a truly inclusive economy requires policies that expand opportunity, strengthen worker power, prevent exploitation, and ensure that everyone who wants to contribute paid labor has the chance to do so.