In Climate Disaster, the Most Vulnerable Continue to Be Disenfranchised

In disasters, vulnerable communities face an environmental apartheid, absorbing the disproportionate burden of the impact. In recovery, they face discrimination.

Climate catastrophe unfolds onto layers of historic disenfranchisement, displacement, and social exclusion that leaves poor people and communities of color bearing the brunt of disasters. Today September 20, marks the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Maria making landfall in Puerto Rico, where communities are still recovering. What has come to pass for Puerto Ricans since then is a prolonged humanitarian crisis driven by a legacy of colonialism and extraction. While this past week the ongoing impacts from Hurricane Florence in the Carolinas have displaced thousands. Extreme weather events like these are not only aggravated by climate change, they also exacerbate existing inequality that results from historic discrimination.

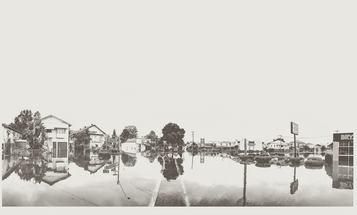

This week Hurricane Florence devastated communities across the Carolinas and Virginia, sending up to 40 inches of rain in some places. The storm has left hundreds of thousands without power, thousands of homes damaged, roads submerged, and at least 36 people dead. While the storm has been downgraded to a tropical depression, floodwaters continue to rise, breaching hog waste lagoons and coal ash sites, leaving behind a toxic slurry of coal ash and toxic waste. Flooding is estimated to get worse in the days ahead, and the worst environmental impacts of the storm may be yet to come.

The crisis carries the echoes of the intense Atlantic hurricane season one year ago, which saw Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria strike the gulf coast and the Caribbean. The intensity of these storms reflects how weather events are becoming more extreme in a climate-changed planet. They also reflect how the impacts of environmental disaster are not borne equally by all.

During Hurricane Harvey, Houston saw over 51 inches of rain. In the petro-chemical industry-rich region, oil and gas facilities and 13 Superfund sites were flooded, creating a toxic soup in affected communities that one year later still pose considerable health threats.

In North Carolina, the poorest communities and communities of color will bear the brunt of the ongoing damage. Historically, Eastern North Carolina is the site of colonies built by former freed slaves. Black communities in the region, many in poor rural areas will have the most difficult time recovering from the storm’s impacts because of historic inequality.

Communities will also face worsened environmental hazards in the wake of Hurricane Florence. Wilmington and other impacted towns hold Superfund sites, and the storm has resulted in the collapse of a coal ash landfill, spilling the toxic ash into flood waters. It is well documented that people of color and low-income people are disproportionately impacted by hazardous sites and pollution.

Not only do the most vulnerable communities face a kind of environmental apartheid absorbing the disproportionate burden of these disasters’ impacts; in recovery, they continue to face discrimination and disenfranchisement. Displaced communities are at risk of losing homes, land, and resources to speculators and developers. They even risk their fundamental rights due to historic discrimination.

A year after Hurricane Maria, many Puerto Ricans are just beginning to rebuild. The slow pace of recovery is not only a failure of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, but reflective of the ongoing colonial relationship of the island to the U.S. government. While Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, President Trump publicly denies their humanity, concocting a delusion that the island did not actually lose the thousands of lives reported.

Displaced Puerto Ricans who have settled in the U.S. face a climate of discrimination and exclusion. A study based on cellphone data found that between October 2017 and February 2018, almost 400,000 Puerto Ricans left the island, and about 150,000 landed in Florida. These U.S. citizens arrived to find themselves scapegoated as Spanish-speaking migrants, and disenfranchised of their rights to equal participation in democracy.

In August Demos filed a lawsuit against the Florida Secretary of State and 32 Florida counties for not providing elections materials in Spanish as the law requires, even as thousands of displaced Puerto Ricans increase the state’s Spanish-speaking electorate. One of the plaintiffs in the case is Marta Rivera, who came to Florida in October after losing everything in Hurricane Maria. In early September, a federal judge granted a preliminary injunction ordering Florida counties to provide bilingual elections materials in time for this November’s election.

Climate change, its toxic impacts, and the displacement it causes aggravate the social exclusion and discrimination faced by communities of color and poor communities. Not only is climate change exacerbated by billionaire fossil fuel executives who fund politicians to block meaningful solutions, it also expands existing social inequality and environmental apartheid. Extreme weather events become “threat multipliers,” increasing health risks to communities already living near hazardous facilities, as in the case of Houston or Wilmington, and displacing communities and exposing them to heightened disenfranchisement, as in the case of Puerto Ricans in Florida.

On this anniversary of Hurricane Maria, as communities in the Carolinas continue to face rising waters, achieving a just recovery will require more than phasing out fossil fuels from our economy. Most importantly, climate justice will require fixing our broken democracy to release the stranglehold of the fossil fuel industry on politicians. It will require radical inclusion of impacted peoples in the political process, so that black and brown bodies are no longer relegated to absorbing the brunt of climate catastrophe.

---

Support a just recovery from Hurricane Florence in North Carolina

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Hurricane Florence Relief Fund, set up by North Carolina WARN, a 30-year old environmental justice organization working with frontline communities in the state.

To learn more ways that you can support grassroots organizations engaged in on-the-ground long-term recovery work please visit A Just Florence Recovery.