Chief Justice John Roberts' Bad History in VRA Decision

When Congress reconsiders the Voting Rights Act this session, they should consider the few pages of history conspicuously missing from Chief Justice John Roberts’ opinion—an opinion that relies not only on bad logic but also bad history.

On logic, Roberts argues in his opinion for the court striking down Section 4 of the VRA: “Things have changed in the South. Voter turnout and registration rates now approach parity […] [a]nd minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels.” In her dissent, Justice Ginsburg points out the absurdity of arguing a policy is unnecessary because it’s been so effective.

On history, Roberts’ opinion evinces no grasp of what made voting rights laws essential in the first place. Roberts presents a narrative of voting rights with two phases, beginning with the ineffectiveness of the 15th Amendment prior to the civil rights movement, and concluding with the ever-increasing parity in voting since the civil rights movement, a straightforward progress narrative that, for him, shows preclearance is no longer necessary. But Roberts argues wrongly that the “first century of congressional enforcement,” following the 15th Amendment, “can only be regarded as a failure,” and in effect, he neglects a chapter of history that demonstrates the danger in eliminating voter protections.

The early career of the 15th Amendment was actually quite promising, thanks in part to aggressive congressional enforcement. According to historians Gabriel Chin and Randy Wagner, “African Americans were a majority or controlling plurality in the states where most lived. African American-backed majoritarian governments controlled the South after the Civil War.” An estimated 2,000 blacks were elected to office in the South during Reconstruction, with hundreds more receiving political appointments, according to historian Eric Foner.

It isn’t that Blacks never had the vote prior to the civil rights movement; Blacks lost the vote. It was precisely the success of the 15th amendment that prompted fears in the South of “Negro domination,” and what we have come to know as Jim Crow. Then, like today, blacks stand to be the victims of their own success.

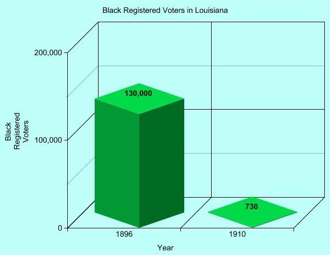

Source: Richard H. Pildes, “Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon.” Constitutional Commentary 17 (2000), p12.

Slate provides a copy of one of the literacy tests used by the state of Louisiana until 1964.

Unprecedented black electoral power was chipped away slowly by a racially hostile government, starting with the 1876 Supreme Court decision in Reese vs. United States that dismantled congressional enforcement of the 15th Amendment. This decision created an opening for southern states to pass a series of voter laws, including poll taxes and literacy tests designed to reduce the number of black voters. The laws craftily avoided mentioning race, thus avoiding the courts’ ire. In Virginia, the adopted home state of several justices representing the Roberts majority, the number of registered black men plummeted from 147,000 in 1900 to 21,000 four years later. In South Carolina, in just twelve years, the number of black voters dropped from 91,870 to 13,000.

Why does it matter that Roberts got this history so wrong? Perhaps Roberts sincerely believes that African Americans did not have regular access to the ballot until the Voting Rights Act was passed, and believes that now that African American and other racial minority voters finally do have high turnout, the government should begin to relax some oversight. What’s clear is that it is much easier to argue that post-Voting Rights gains do not need further congressional protection if one has amnesia about historical gains that were undone once before.

* Haley Swenson contributed to this piece.