Americans Should Care More About Money in Politics

The recent Scott Walker allegations have brought the question of money in politics post Citizen’s United to the forefront. At the Monkey Cage blog, Brandon Rottinghaus points to his research that, “as opposed to other kinds of scandals (sexual, etc.), political scandals like Walker’s are harder to prove and don’t affect the survival of the governors involved in them.” This is bolstered by research by Scott Basinger who finds that corruption scandals (like bribery) hurt candidates significantly, sex scandals hurt them moderately but campaign finance scandals have little effect on the candidate’s re-election margin.

The most likely explanation is that, while the minutia of campaign finance laws are complex, extra-marital coitus is easy for most Americans to understand. Take the “smoking gun” of the Walker case, as reported by Jonathan Chait, an email sent from Walker to Karl Rove discussing his campaign strategist R.J. Johnson’s control of independent expenditures:

Bottom-line: R.J. helps keep in place a team that is wildly successful in Wisconsin. We are running 9 recall elections and it will be like 9 congressional markets in every market in the state (and Twin Cities)

Without a pretty deep understanding of post-Citizens United campaign finance law, this email indicates nothing. Independent expenditures are used to finance political communication that is “expressly advocating the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate.” However, as the name implies, these communications are meant to be independent and therefore, “not made in cooperation, consultation, or concert with, or at the request or suggestion of, a candidate, a candidate's authorized committee, or their agents, or a political party committee or its agents.”

The email shows rather clearly that such expenditures were made in cooperation with Walker.

But what exactly constitutes coordination is at odds with the conventional understanding of the term. Contrast this with the Bob McDonnell case, in which he accepted gifts from the CEO of Star Scientific and then became a spokesman for their product, or John Edwards' affair during his wife’s struggle with cancer.

There is also the problem that money in politics is often seen as immaterial. In shutting down a previous investigation of coordination, U.S. District Judge Rudolph Randa writes, “[c]oordination does not add the threat of quid pro quo corruption that accompanies express advocacy speech… O‘Keefe and the Club obviously agree with Governor Walker‘s policies, but coordinated ads in favor of those policies carry no risk of corruption because the Club‘s interests are already aligned with Walker and other conservative politicians… Such ads are meant to educate the electorate, not curry favor with corruptible candidates." That is, Randa is arguing that because the Club for Growth (a conservative advocacy organization) is generally aligned with Scott Walker, their coordination will not lead to quid pro quo corruption (i.e. you give me this, I’ll give you that).

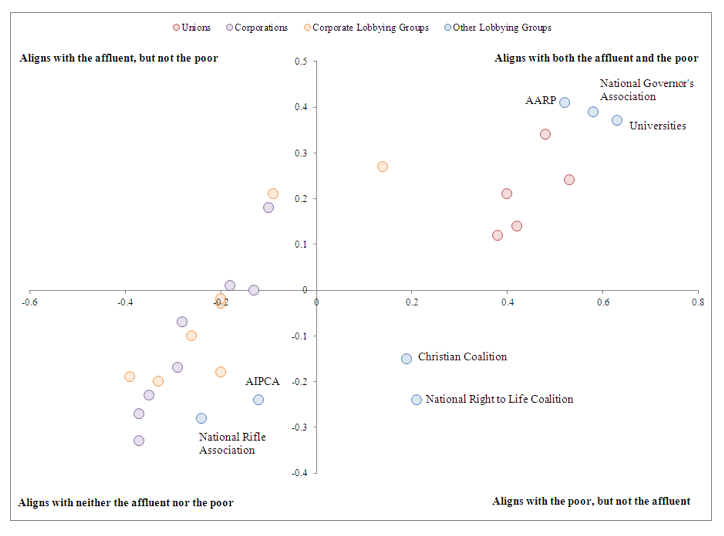

Demos lawyers have repeatedly argued that this definition of corruption is incredibly problematic legally, but it also betrays an ignorance of the literature on money in politics. In Stacked Deck, Demos found that the very affluent people who donate to political campaigns often have preferences that diverge strongly from most Americans, for a high minimum wage, which 78% of the general population supports, but only 40% of the wealthiest one percent do. Club for Growth is a corporate advocacy group, which as I’ve shown before, diverge strongly from the preferences of most Americans.

David Broockman and Joshua Kalla find that politicians are far more likely to arrange meetings with constituents who have donated to their campaign than those who have not.

Judge Randa worries that, “the larger danger is giving government an expanded role in uprooting all forms of perceived corruption which may result in corruption of the First Amendment itself. … As other histories tell us, attempts to purify the public square lead to places like the Guillotine and the Gulag.” But rather the opposite has happened in Connecticut, where a voluntary public financing system has lead to legislators spending more time with constituents and have more responsive policy-making.

Other studies find that states with stricter campaign finance regulations are more responsive to the interests of the poor. Patrick Flavin finds that corporate lobbying restrictions reduce representational inequality (the extent to which legislators are more responsive to the preferences of their wealthy constituents).

The public’s response to scandal is odd; sexual indiscretions tell us little about how effectively a politician will govern, while money in politics affects the governance process dramatically. It's time to change our focus.